Overlooked Adverse Reactions: Hypertension Part I

Before some cases of strokes, heart attacks, or myocarditis comes high blood pressure. A look into hypertension and the role of SARS-COV2 in elevated hypertension.

Following along with the theme of overlooked adverse reactions (prior one looking at GI issues) is one all-too common disease: high blood pressure, or hypertension.

A few weeks ago Stephanie Brail of Wholistic made a post on cardiovascular issues in some vaccine recipients, such as one individual named Ryan Cunningham who appears to be suffering from heart failure post-vaccination, as well as Dr. John Campbell who explains his process of dealing with the UK’s VAERS system when trying to report his hypertension post-vaccination.

A relevant timestamp is provided for Dr. Campbell’s video below:

From Dr. Campbell’s account he began measuring his blood pressure in January 2022 (with his last vaccination occurring in November 2021) and noticed his blood pressure was elevated. Following the next few months it appears that his blood pressure continued to steadily increase leading him to have to take blood pressure medications—much to his chagrin.

It was from this post I actually became curious about this relationship between vaccination and hypertension (something that should, on the surface, be more apparent than I originally thought), but shelved my thoughts at the time to work on my microbiome post.

However, if hypertension post-vaccination is widespread, then it may actually be an indicator for other, more severe adverse events post-vaccination.

Note: A discussion on COVID vaccines and hypertension as an adverse reaction will be saved for the next post. This one will provide general information on hypertension and how it can be caused by SARS-COV2.

Defining Hypertension

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is defined as a persistent elevation of pressure within the arteries of one’s body above what is typically found in healthy individuals.

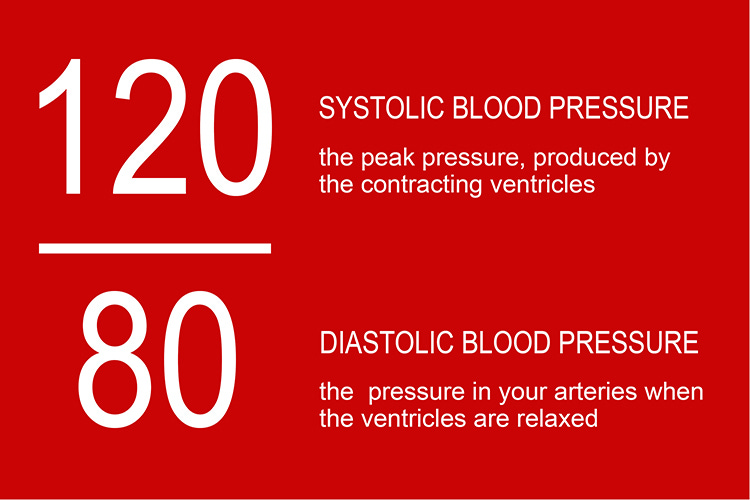

Hypertension is measured as two numbers, usually represented as a fraction even though the numbers are counted independently. The top number is a measure of systolic pressure (given in millimeters of mercury, or mmHg), which is the pressure from a heartbeat that pumps blood through vessels.

In contrast, diastolic pressure (also measured in mmHg) is the pressure when the heart and blood vessels relax, with the heart refilling with blood.

Measures of blood pressure are usually given with systolic pressure at the top and diastolic pressure at the bottom.

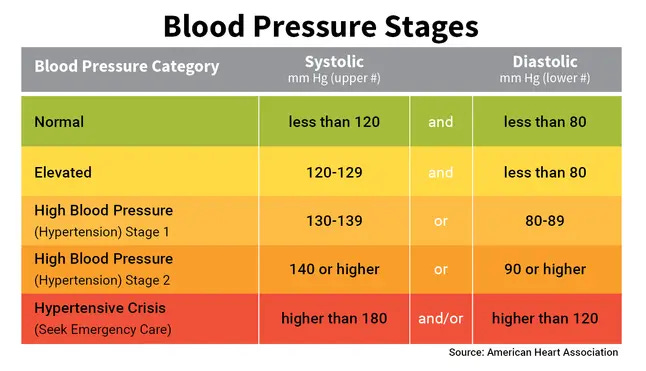

Hypertension is categorized by various stages, and elevation in either systolic or diastolic blood pressure may be suggestive of high blood pressure. In general, elevated systolic levels or both systolic and diastolic are associated with hypertension. However, in rarer cases diastolic pressure may be elevated without any elevation in systolic pressure, recognized as isolated diastolic hypertension1.

Hypertension is one of the most common diseases in the US, with an estimate reported by the CDC suggesting that nearly half (~47%) of all US adults may have hypertension.

Hypertension itself isn’t the main problem, but rather the downstream consequences that may arise from persistent, uncontrolled hypertension.

For instance, hypertension is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cardiac death, kidney disease, and strokes2. Hypertension is also one of the greatest causative factors in myocardial infarctions (heart attacks)3.

The widespread damage caused from hypertension may be owed to the stress placed on the heart and other organs. Elevated pressure may also cause damage to the endothelial lining of blood vessels as blood must be pushed through with higher force than would be expected, which can add to the widespread complications.

Most diagnoses of hypertension are of unknown etiology. That is, the cause for the hypertension is generally not know.

Age, sex, ethnicity, genetics, comorbidities, diet, lifestyle, stress, and sympathetic nervous system dysfunction all influence hypertension, suggesting a likelihood of multiple factors contributing to the disease.

Symptoms of Hypertension

What makes hypertension rather insidious is that it generally presents as asymptomatic. Even when blood pressure levels may become deadly a person may not be aware that they are experiencing hypertension until a severe cardiovascular event occurs.

As Dr. Campbell notes in his video most people may be unaware that they have hypertension unless they get their blood pressure measured to confirm hypertension.

But even if hypertension presents with symptoms they may be very vague such as nausea, headaches, and shortness of breath, which may be mistaken for other symptoms.

Because of a general lack of symptoms hypertension has been considered a “silent-killer”4.

Managing Hypertension

In many cases hypertension is managed with lifestyle changes such as better eating, weight management, stress management, and exercise. The use of antihypertensive medications may also help with managing hypertension.

Antihypertensive medications encapsulate a broad field of medications with actions that usually result in the lowering of blood pressure.

The American Heart Association provides a list of various antihypertensive medications, as well as their general mechanism of action and typical examples of such medications.

In short, some medications act as diuretics and reduce sodium levels in the body to help reduce blood pressure. Some others may act as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which reduce the conversion of angiotensin into other metabolites. Some medications may act as angiotensin II (Ang-II) receptor blockers, which block the binding of angiotensin II to receptors and preventing the cascading responses. Note that ACE inhibitors prevent the conversion of angiotensin into other metabolites, whereas Ang-II blockers prevents angiotensin already present from binding and signaling.

Because of the scope of antihypertensive medications this review will not dive deeper into the various classes unless necessary. Instead, I suggest looking at the AHA website for a general overview.

SARS-COV2 & Hypertension

As is well-known SARS-COV2 has an affinity for ACEII receptors.

ACEII is a key component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS)5, a system comprised of peptide hormones involved with blood pressure and other physiological systems.

One peptide hormone, angiotensin II (Ang II), is synthesized from angiotensin 1 via angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). Ang II has been known to increase inflammation, activate immune cells, contribute to vasoconstriction, increase fibrosis, and the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by binding to angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1R).

Ang II can then be converted into Ang-(1-7) by ACEII. In contrast to Ang II, the other angiotensin peptides have an opposite physiological effect, providing anti-inflammatory responses, reducing oxidative damage, and contributing to vasorelaxation.

In essence, the balance between Ang-II and Ang-(1-7) is critical for managing hypertension and maintaining RAS homeostasis.

During a SARS-COV2 infection the virus binds to ACEII receptors, competing with Ang II for binding. Interestingly, the binding of SARS-COV2’s spike protein with ACEII is also known to downregulate ACEII expression, contributing to disease progression and symptom severity.

The consequences of both of these processes (both competition and downregulation of ACEII) leads to the eventual elevation of circulating Ang II, disruption of the Ang II/Ang-(1-7) ratio, and loss of RAS homeostasis.6

The role of ACEII with respect to SARS-COV2 has been one of high controversy.

On one hand, elevated levels of ACEII may attenuate the negative consequences of ACEII downregulation and competitive binding between Ang-II and SARS-COV2 with ACEII receptors. However, greater levels of ACEII may make one more susceptible to viral invasion given the abundance of vulnerable receptors.

In contrast, lower ACEII levels may reduce binding availability for SARS-COV2 and thus may limit viral infection. However, any viral infection may lead to quick dysregulation of RAS and buildup of Ang-II, causing hypertension and worsening symptoms7.

Nonetheless, the direct action of SARS-COV2 on RAS is well-known and is a key feature of the virus’ pathogenesis.

However, assessment of hypertension as a consequence of SARS-COV2 infection suffers from several confounding variables.

Lack of baseline blood pressure information makes it difficult for researchers to discern whether a hospitalized patient may be experiencing hypertension from COVID or independent of COVID. Although a prior record of hypertension wouldn’t be hard to figure out, many patients may go undiagnosed prior to presentation at a hospital given the lack of symptoms associated with hypertension.

There’s also the fact that clinical settings may lead to an inherent increase in blood pressure; a phenomenon known as white-coat hypertension8. Lack of control for this phenomenon may further confound the incidences of hypertension associated with COVID.

With that being said, and given these limitations, several studies have suggested that SARS-COV2 infection may lead to a supposed acute Ang-II storm (Angeli, et al.9):

The failure of the counter-regulatory RAS axis, characterized by the decrease of ACE2 expression and generation of the protective Ang1,7, appears to be strictly implicated in the development of severe forms of COVID-19 [1,2,4,39,40]. More specifically, ACE2 internalization, downregulation and malfunction predominantly due to viral occupation, dysregulates the protective RAS axis with increased generation and activity of Ang II and reduced formation of Ang1,7 [1,2,4].

This has been corroborated by the findings of recent investigations supporting the evidence of the development of an “Ang II storm” [41] or “Ang II intoxication” [42] during the SARs-CoV-2 infection [[2], [3], [4],[43], [44], [45]].

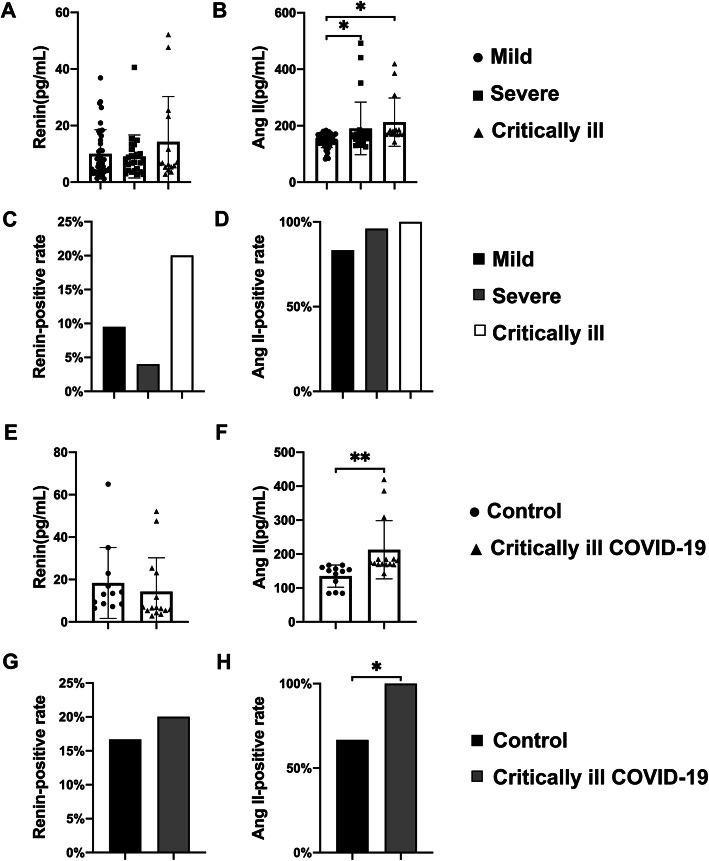

One of the first studies measuring Ang II levels was conducted by Wu, et al.10 where 82 supposedly non-hypertensive SARS-COV2 patients were measured for both Ang-II and renin levels. Measures were compared to 12 critical, unrelated hospital patients who served as controls.

The study noted higher rates of Ang-II relative to controls, with around 90% of all SARS-COV2 patients and 100% of critically ill patients showing Ang-II levels higher than controls. It’s important to note that statistical significance may be driven by a select number of outlier patients, and that levels higher than control should be seen as a relative, not quantitative, term.

The renin results were less profound, with only around 12% of SARS-COV2 patients showing elevated renin levels relative to controls.

This study comes with several caveats, but it’s been generally argued that these results may suggest acute RAS dysfunction with both ACEII binding and internalization of SARS-COV2, as well as downregulation of ACEII expression causing a sudden increase in Ang-II.

Angeli, et al. goes on to provide additional information on some of literature with respect to Ang II levels in SARS-COV2 patients. The excerpt also notes possible risk factors:

There was a direct association between plasma Ang II levels and COVID-19 severity [46]. Similarly, a clinical investigation aimed to predict disease severity in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in Shenzen, demonstrated that Ang II levels in the plasma samples were significantly increased and linearly associated with viral load and lung damage in critically ill patients [47]. Moreover, the degree of ACE2 deficiency (more pronounced in specific conditions including older age, cardiovascular disease and risk factors) are associated with more severe forms of COVID-19 [1,2,8,11,12,48,49]. Accrued evidences in the field showed that specific conditions associated with ACE2 deficiency and RAS dysregulation [13], [14], [15] (including older age [48,[50], [51], [52]], male sex [53], the presence of diabetes [54,55], lung disease [56], and history of cardiovascular events [57], [58], [59], [60], [61]) are well established risk factors for increased disease severity in COVID-19 (2-1) [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12] (Fig. 1, middle panel).

Given the mechanisms outlined above one may assume that hypertension may be considered a risk factor for severe COVID. It’s certainly true that early remarks by medical professionals raised serious concerns over hypertension’s role.

Unfortunately, the data has been mixed, with some studies finding a correlation between hypertension and worse outcomes in COVID patients, as summarized in a review from Peng, et al.11:

The first large-scale analysis of the data from 1590 laboratories found that hypertension was the most common comorbidity (16.9%), followed by diabetes (8.2%).7 Cox regression analysis adjusted for age and smoking status showed that hypertension was a significant risk factor for poor outcomes including admission to an intensive care unit, requirement for invasive ventilation, or death.7 Wu et al reported that the overall case-fatality rate was 2.3% (1023 deaths among 44,672 confirmed cases), and it was elevated in comorbid conditions—6.0% in patients with hypertension.16 Guan et al analyzed 1099 patients infected with COVID-19, including 173 patients with severe illness: The overall incidence of hypertension was 15% (165/1099), which rose to 23.7% (41/173) in patients with severe COVID-19 illness, and dropped to 13.4% (124/926) in those with nonsevere illness. Furthermore, severe COVID-19 patients with hypertension were more likely to reach adverse end points (35.8% vs. 13.7%).10

Again, these studies should be met with hesitancy given the labile nature of hypertension, as blood pressure measures within the hospital may stem from a with/from paradigm. Many patients with hypertension may also be older with other comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease which may also increase the risk of COVID severity. The latter caveat may infer a selection bias where hypertensive patients may be captured in the data, but may not necessarily be directly related to worse outcomes.

Hypertension is one of the most insidious diseases, with many adults likely suffering dealing with blood pressure issues in some manner. The prevalence of hypertension in the Western world may suggest a consequence of modernity and an aging population.

Regardless, the fact that hypertension is not recognized unless measured adds to the insidious nature of the disease, as the consequences of hypertension may not become apparent until a sudden event such as a cardiovascular event or a stroke.

Due to the mechanisms of SARS-COV2’s utilization of ACEII it makes sense that concerns may arise as to whether SARS-COV2 may be exacerbated in those with hypertension. The evidence is mixed, and likely confounded by the comorbidities of hospitalized patients.

More importantly, given that many of the COVID vaccines deployed utilize the spike protein, it raises questions as to whether the vaccines may also influence hypertension, as seen in the case of Dr. Campbell.

As hypertension goes unrecognized in a majority of individuals, and given its role as a silent killer, one may wonder whether the sudden deaths and the serious complications post-vaccination may be related in some ways to the hypertensive “spike effect” from the vaccines.

This will be explored further in the next post.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Yano, Y., Kim, H. C., Lee, H., Azahar, N., Ahmed, S., Kitaoka, K., Kaneko, H., Kawai, F., Mizuno, A., & Viera, A. J. (2022). Isolated Diastolic Hypertension and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Controversies in Hypertension - Pro Side of the Argument. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979), 79(8), 1563–1570. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.18459

Fuchs, F. D., & Whelton, P. K. (2020). High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979), 75(2), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14240

Pedrinelli, R., Ballo, P., Fiorentini, C., Denti, S., Galderisi, M., Ganau, A., Germanò, G., Innelli, P., Paini, A., Perlini, S., Salvetti, M., Zacà, V., & Gruppo di Studio Ipertensione e Cuore, Societa’ Italiana di Cardiologia (2012). Hypertension and acute myocardial infarction: an overview. Journal of cardiovascular medicine (Hagerstown, Md.), 13(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283511ee2

Kalehoff, J. P., & Oparil, S. (2020). The Story of the Silent Killer : A History of Hypertension: Its Discovery, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Debates. Current hypertension reports, 22(9), 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-020-01077-7

RAS is a complex hormonal system responsible for regulating blood pressure through ion control, water absorption, and vascular tone. RAS may also be referred to as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system with the appropriate abbreviation RAAS.

A quick review on RAS can be found below:

Fountain JH, Lappin SL. Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System. [Updated 2022 Jun 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470410/

South, A. M., Diz, D. I., & Chappell, M. C. (2020). COVID-19, ACE2, and the cardiovascular consequences. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology, 318(5), H1084–H1090. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00217.2020

Verdecchia, P., Cavallini, C., Spanevello, A., & Angeli, F. (2020). The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. European journal of internal medicine, 76, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037

Given the nature of this phenomenon white-coat hypertension may increase the risk of a cardiovascular event for hospitalized patients.

Angeli, F., Reboldi, G., Trapasso, M., Zappa, M., Spanevello, A., & Verdecchia, P. (2022). COVID-19, vaccines and deficiency of ACE2 and other angiotensinases. Closing the loop on the "Spike effect". European journal of internal medicine, 103, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2022.06.015

Wu, Z., Hu, R., Zhang, C., Ren, W., Yu, A., & Zhou, X. (2020). Elevation of plasma angiotensin II level is a potential pathogenesis for the critically ill COVID-19 patients. Critical care (London, England), 24(1), 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03015-0

Peng, M., He, J., Xue, Y., Yang, X., Liu, S., & Gong, Z. (2021). Role of Hypertension on the Severity of COVID-19: A Review. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology, 78(5), e648–e655. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000001116

Thankyou for this great article. I am Covid-19 vax injured. My BP started to rise after my first Pfizer vax. After the second one in June 2021, I was diagnosed with Pericarditis and my BP is always in hypertension stage 1. When I’m walking slowly or doing pilates, it goes up into stage 2. I always have constant chest pain and shortness of breath and fatigue. I also have supraventricular tachycardia and occasionally paroxysmal hypertension which leads to syncope.

I’ve been on beta blockers (Bisoprolol) since my diagnosis over 16 months ago and this hasn’t lowered it. I’ve been put on two rounds of colchicine for the peri, but this hasn’t worked. I’ve started trialling hawthorn and increasing potassium and magnesium to see if this makes a difference because I still have another month to wait till I see a cardiologist to have a pacemaker inserted and the hospitals keep sending me home saying nothing is wrong, so I have stopped calling an ambulance now. All my friends and family who are vaxed all now have raised blood pressure and are on medications as well as myocarditis and pericarditis. One has had a myocardial infarction and another has hed two stents put in. This has caused an epidemic of heart disease.

Great article! Ooooh, am I selfish in hoping you look at supplements or dietary tips to help hypertension :))But I do want to stress that I hop you enjoy all of your writing- I was sad to hear that some of your articles left you burnt out from all of the data you have to pore over. I can only imagine how frustrating that would be if then the data didn’t lead to a clear answer.

Sorry but another neophyte question. If the public were to get higher levels of hypertension and then were given diuretics as the main treatment- could that actually make things worse if the cause is the endothelial disorder caused by Lipid nanoparticles in the mRNa shots? I guess I’m wondering if - like in the opening days of the covid outbreak when they thought ventilators were the answer but ended up killing untold numbers- are they prescribing a medicine that is making this condition worse because they don’t acknowledge the underlying cause?