Has an actual criteria for Long COVID been constructed?

A recent JAMA article seems to argue so.

There’s been a growing debate over the concept of Long COVID and whether it truly exists, or is a social construct or term used prolong the COVID hysteria, with many people usually citing poorly-constructed, self-reported studies that usually fail to delineate signal from noise.

This is, for the most part, due to the fact that the diagnostic criteria for Long COVID is so broad that it can capture just about anyone as having Long COVID irrespective of prior COVID infection history.

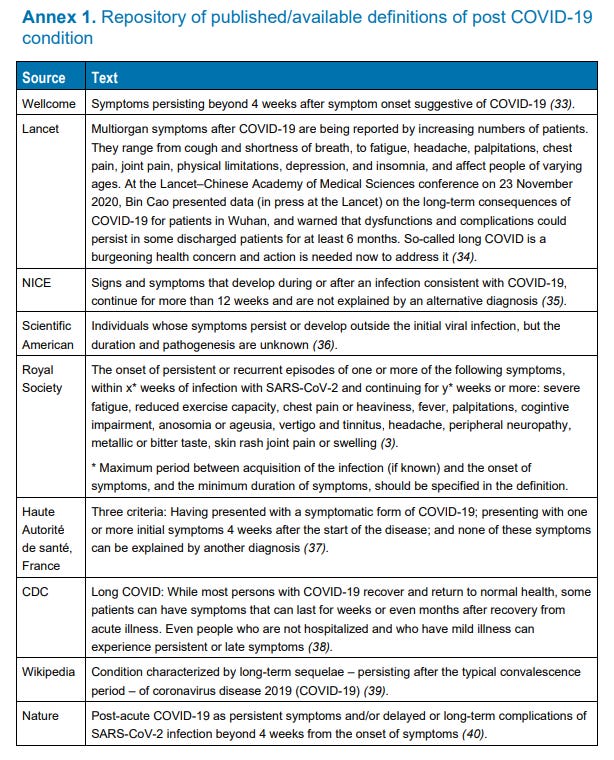

Note that this is the definition of Long COVID constructed by the WHO1, which is extremely broad in its definition:

When covering the Norwegian Long COVID study I made the mistake of suggesting that the WHO diagnostic criteria for Long COVID requires at least one symptom be met. That’s not true, as the phrasing of the Supplemental Material notes that the criteria formed was based on an operationalization of the WHO’s Long COVID definition.

That is, the diagnostic criteria used in that study was constructed based on the WHO’s definition, and thus is not likely to be similar across other Long COVID studies (a correction has been added to that post in regards to that error). Note that this correction still doesn’t change the broad and highly ambiguous use of such a definition for the Norwegian study.

Also, note that the definition constructed by the WHO appears to be based on surveys sent out to patients, clinicians, and researchers across the world asking them what they would include within the definition of Long COVID, so there really has been no truly objective definition constructed. This can also be seen in how journals differ greatly in the definitions they tend to use.2

Because of these ambiguities in definition and diagnoses, I generally refute the claim that Long COVID doesn’t exist by way of these studies, as no one seems to have provided a clear criteria for diagnosis.

That is, until a study from last week published in JAMA3 which seems to have constructed a “workable” definition of Long COVID:

The study is part of an ongoing study, using surveys from individuals both infected or uninfected with COVID collected from the WHO’s RECOVERY trial.

Although this study captures patients in both pre-Omicron and post-Omicron eras of COVID, it also captures people who have been vaccinated, and so the results are not a clear scope of Long COVID due to infection.4

Patients were considered for the possible categorization of Long COVID if they were infected with SARS-COV2 prior to study enrollment (verified via serology testing) and had a first study visit 6 months or more after an indicated index date (index date is not defined, but appears to be specific dates used to stratify between pre-Omicron and post-Omicron time periods, which appears to use December 1, 2021 as the specific date).

Note that the intent of this study was to start with a very broad list of symptoms and narrow them down to a select few which appeared to correlate with Long COVID based on odds ratios and frequency of symptom reports.

Assessment of probable symptoms related to Long COVID first started with a broad list of 44 symptoms, with patients provided a survey asking which symptoms they had. Symptoms that were reported with frequencies higher than 2.5% were included as possible Long COVID symptoms for further assessment.

In that regard, initial survey results noted that 37 of the 44 symptoms listed met with a symptom frequency over 2.5%, with some showing large differences between those who were previously infected and those who were not5:

In the full cohort, 37 symptoms had frequency of 2.5% or greater and aORs were 1.5 or greater (infected vs uninfected participants) for all 37 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Symptoms (using severity thresholds) with more than 15% absolute difference in frequencies (infected vs uninfected) included postexertional malaise (PEM) (28% vs 7%; aOR, 5.2 [95% CI, 3.9-6.8]), fatigue (38% vs 17%; aOR, 2.9 [95% CI, 2.4-3.4]), dizziness (23% vs 7%; aOR, 3.4 [95% CI, 2.6-4.4]), brain fog (20% vs 4%; aOR, 4.5 [95% CI, 3.2-6.2]), and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (25% vs 10%; aOR, 2.7 [95% CI, 2.2-3.4]).

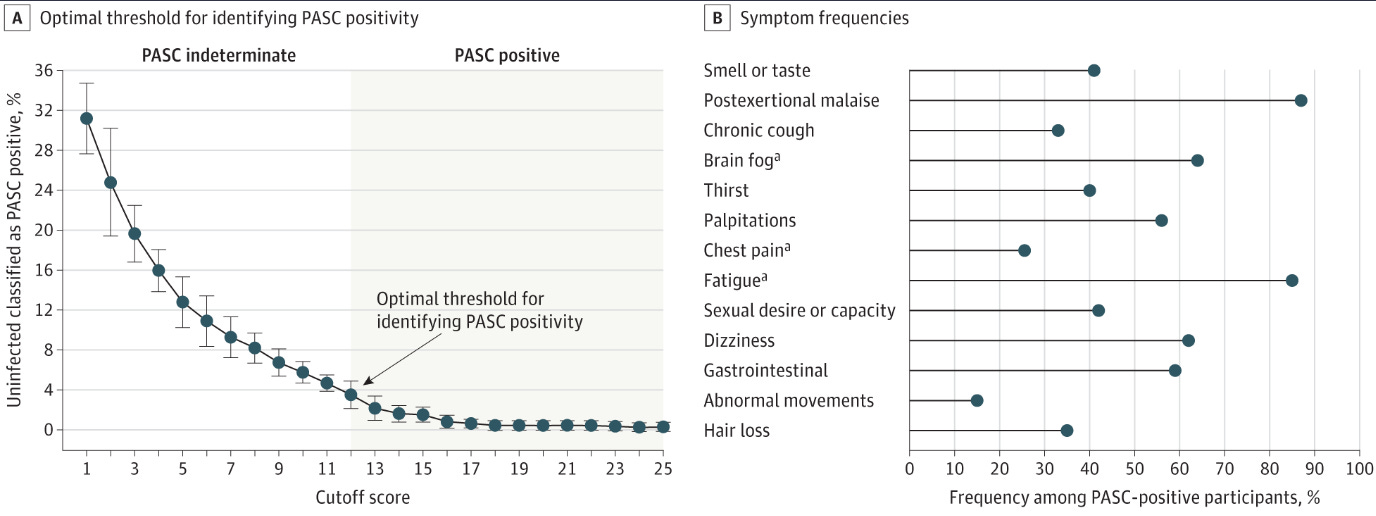

In order to delineate possible Long COVID (PASC Positive) from noise, a PASC score was eventually provided to 12 symptoms.

I’m a bit confused as to how these 12 symptoms were chosen, but it appears that the researchers utilized a method called Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, or LASSO. LASSO takes variables and constructs linear regressions, and it appears that based on these regression LASSO assigned each symptom a PASC score, likely due to measures of symptom frequency or odds ratios being used to construct these regression. Symptoms that received a PASC score appear to be the symptoms included in PASC assessment.

To clarify, the symptom Hair Loss appears to have received a PASC score of 0 based on LASSO, and thus was likely removed as a symptom worth considering. It’s likely that many other symptoms that received a score of 0 were removed as symptoms of interest as well, which narrowed down the set to the above 12 which were given some sort of score.

Using these PASC scores, a patient was considered to qualify as having PASC/Long COVID if they received an overall PASC score above 12 based on the symptoms that they listed.

To provide an example, let’s use the model list of symptoms with their corresponding PASC scores:

Suppose that a patient lists the following symptoms on their survey (corresponding PASC scores shown on the side):

Hair loss (0)

Dizziness (1)

Fatigue (1)

Abnormal Movements (1)

Anxiety (assumed to be 0)

Loss of smell/taste (8)

Skin Rash (assumed to be 0)

Brain Fog (3)

If we add up these symptoms we would get an overall PASC score of 14. In this case, the above patient would be considered to have qualified for PASC, or be Long COVID positive.

There are a few problems with this approach. However, it’s one of the only approaches which seems to provide a more stringent inclusionary/exclusionary criteria, in that specific symptoms must be met, and enough symptoms that warrant a consideration of PASC.

Put another way, the only way to receive a PASC positive diagnosis would be to either list several low-scoring symptoms such as fatigue or dizziness, which are rather broad symptoms, or to list symptoms that are more closely related to SARS-COV2 such as alterations in smell/taste as well as postexertional malaise.

This is far different than the criteria used in the Norwegian study, as it at least provides a far better selection criteria and helps to separate out infected/uninfected patient symptoms, as shown in the following graph:

Based on Figure 2A, it’s likely that a PASC score of 12 was chosen as it was the first point to fall under the 5% false positive cutoff for uninfected patients.

Note that in using this criteria for PASC qualification, those within the infected group had a PASC qualification percentage of ~23% while the uninfected group had a percentage rate of ~3.7% qualifying as PASC positive- a marked difference relative to other studies which noted a comparable or not significant difference between infected/uninfected groups.

A move towards better quantifying Long COVID

So far, studies on Long COVID have relied far too heavily on ambiguous criteria, leading to an inability to properly delineate actual cases of Long COVID from symptom overlap due to other circumstances.

This study from Soriano, et al. provides one of the first approaches to actually dealing with this issue of ambiguity by assigning scores to symptoms and providing a cutoff for meeting a PASC diagnosis.

Interestingly, the evidence from this study also appears to note that PASC symptoms are more common and more severe in those infected pre-Omicron relative to those infected post-Omicron, suggesting that severity of illness may correlate with Long COVID risk.

It’s important to note that this study is not without flaws. For one, the inclusion of vaccinated individuals means that another variable is thrown into this assessment that may explain the symptoms and scores seen.

Note that there have been several reported cases of Long COVID-like symptoms in some people who were vaccinated, and was even reported in a Science article published last year:

This shouldn’t come as a surprise given the number of reported adverse reaction cases post-vaccination.

Because of these circumstances, one should consider the fact that reported symptoms of PASC may be related to vaccination and not infection. Of course, a way of controlling for this variable would either be to include unvaccinated individuals as was done in the Norwegian study, or to provide a survey and ask for symptoms prior to vaccination but post-infection.

There’s also the fact that many symptoms that may relate to Long COVID may have been given a PASC Score of 0, and thus may not reflect the true number of PASC cases:

Although only 12 symptoms contributed to the PASC score, other symptoms correlated with this subgroup are individually important, considering their potential adverse impact on health-related quality of life.

So there’s a bit here that leaves me wanting, as the construction of this criteria isn’t without issues. Nonetheless, it’s one of the only attempts out there to actively attempt to provide a basis for assessing Long COVID, suggesting that such a feat is at least possible.

It would be interesting to see how many researchers may comb through their old datasets and see if they can construct their own criteria for Long COVID. But so far, this appears to be one of the only instances of providing a concrete diagnostic tool for discerning PASC from noise. Hopefully more researchers will follow suit so that a better definition and diagnostic criteria can follow.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Soriano, J. B., Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P., Diaz, J. V., & WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition (2022). A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 22(4), e102–e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9

The following is a collection of Long COVID definitions that the WHO compiled. It can be found on their website via a download link to the same Soriano, et al. study linked above. However, the link from PubMed seems to be missing this table in its Supplemental Material.

Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA. Published online May 25, 2023. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.8823

"Because of these circumstances, one should consider the fact that reported symptoms of PASC may be related to vaccination and not infection.": How true, my thoughts exactly.

You've got to give them some credit, though. It's not all that easy to construct diagnostic criteria like these in order to hide what's actually happening.

As a life-long experiencer of some strange form of chronic fatigue, I could easily qualify for Long Covid, except that I've never had the virus and I've never had the shots, and this has been going on for the better part of seven decades. I suspect it to be mitochondrial, and I wouldn't be the least surprised to learn that Long Covid is too, but let's not be getting sidetracked with actual possible causes. Symptoms are what matters.

All I can say is WOW...

Also, I have "it" and it gets worse everyday...

Is there a magic pill...?