Long COVID symptoms do not be downplayed for argumentative reasons

A growing trend of "X denialism" is not needed to still prove a point over vaccine harms and draconian mandates.

Correction 6/1/2023: Below I remarked that the diagnostic criteria for Long COVID used by the WHO was one that suggested that at least one symptom listed must be met. This is not correct, as the WHO does not have a specific set of criteria for Long COVID. As noted in the image, the word “operationalization” was used, which infers that the researchers constructed their own diagnostic criteria while using the backbone of the WHO definition in order to do so. That means that this definition is likely not to be used across other Long COVID studies, and that diagnostic criteria may be highly subjective and dependent upon the researcher’s construction. Apologies for overlooking that aspect.

The following is not intended to be a refutation of Dr. Prasad’s post, but intended to add some context to argue that there’s a lot of issues with Long COVID studies in general, which are difficult to control for and thus can’t provide definitive evidence one way or another. I consider Dr. Prasad to be doing a lot of good work. But with that said, I can raise some good-faith criticisms in some assessments. I will also concede that I consider Dr. Prasad, as well as many others, to be far more intelligent than I and leave room for him having much more knowledge on the subject.

As I’ve mentioned previously there’s been a strange growing trend of denying factors related to certain aspects of COVID. This includes whether there was a virus (virus denialism), whether myocarditis is actually associated with a SARS-COV2 infection (myocarditis denialism), and even growing arguments against the existence of Long COVID (Long COVID den… you get the picture).

For the most part, I have found these arguments to be rather contentious, but not for the reasons people may believe.

For instance, I think it’s fully up to people to argue whether they believe viruses are pathogenic or not (an argument over terrain vs germ theory in disease) if they do so from a perspective based on evidenced-reasoning.

However, it's one thing to argue that evidence suggests that viruses aren’t pathogenic; it’s another to deny their pathogenicity if it means not taking up bandwidth in critical thinking.

It’s the latter that I have seen growing in the discourse; deny the existence of X if it makes it so less critical thinking is required.

There’s also room for an argument that “denial of X” may be done if “acknowledgement of X” may concede some ground to so-called adversaries, as Brian Mowrey has run afoul of doing by arguing that the vaccines, even with their questionable safety and unknown long-term effects, may still provide some protection to those who receive them.

I would argue that Brian Mowrey’s point here is correct, in that we don’t need to argue whether or not vaccines are super effective when the basis of arguing against mandates is one of ethics and bodily autonomy.

But this argument is one that appears to be going to the wayside, and moving more towards a narrative that removes circumstances if it makes for a more “cleaner” or “cohesive narrative”.

Thus, several people have argued that myocarditis does not actually occur in those infected with SARS-COV2, which have unfortunately utilized data from an analysis that actually includes case reports of myocarditis:

And this extension of denialism has, unfortunately, moved into the domain Long COVID as well.

Very recently Dr. Vinay Prasad, who I would argue have raised very good criticisms against masking, made a post in which he argued against a link between SARS-COV2 infection and Long COVID in children based on a Norwegian study:

Here, I’ll argue that Prasad isn’t entering into the territory of denialism, but looking at studies and arguing that the evidence provided does not argue in favor of Long COVID being widely prevalent (of which there is reason to make such an argument).

The study was published in JAMA as have many other Long COVID studies (Selvakumar, et al.1):

The study looked at Norwegian adolescents and young adults during the Alpha wave and examined prevalence of post COVID-19 condition (PCC) and post-infection fatigue syndrome (PIFS). Baseline demographic data was collected, as well as PCR tests conducted for SARS-COV2 positivity and blood samples. Follow-up occurred at 6 months post baseline measures, and a select few participants were measured at 12-month follow-up (not included in this report):

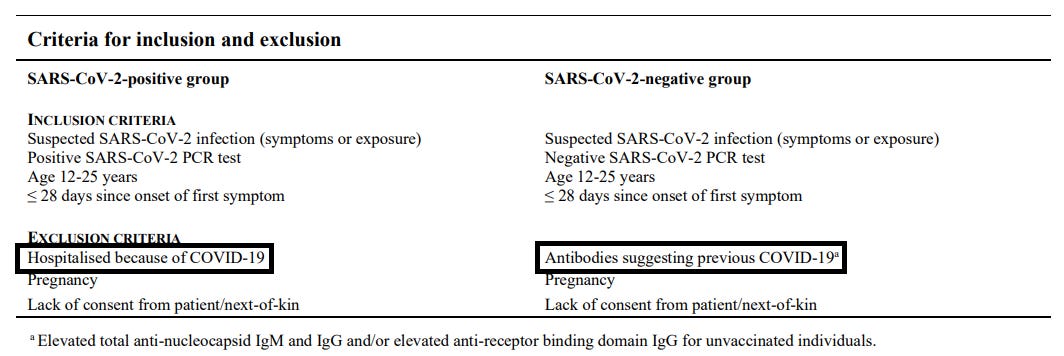

The project entitled Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 in Adolescents (LoTECA) is a prospective cohort study investigating the long-term consequences of acute infection with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in non-hospitalised adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 25 years (ClinicalTrials ID: NCT04686734).1 The project enrolled a total of 404 individuals with a positive Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2-positive group), as well as 105 individuals with a negative PCR test (SARS-CoV-2-negative group) for baseline investigations (cf. flowchart below). After six months, a follow-up investigation was carried out in all participants. Participants who met criteria for fatigue caseness at six months (Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire total sum score ≥ 4, bimodal (0-0-1-1) scoring of single items, cf. paragraph 1.6 below) were recalled for a second follow-up investigation at 12 months. The present paper reports data from baseline and six months follow-up only. The 12 months follow-up appointments was completed June 2022. At each time point, participants completed a standardised assessment program at our study center lasting about 1.5 hours, and encompassing: a) clinical interview and examination; b) functional testing; c) sampling of biological material; and d) completion of a questionnaire. Further details are provided in the sections below.

Note here that non-hospitalized patients were included, meaning that associations between severe COVID and long COVID symptoms were not conducted, and considered one of the limitations of this study. Also, this study cannot be extended to other age groups as it examined adolescents and young adults in particular (which Prasad mentions in his title):

Furthermore, it is unclear to what extent the results of the present study are applicable to those with more severe acute COVID-19, as persistent symptoms seem to be more common and have been found to be associated with other risk factors in hospitalized patients.47-49 Also, the present study included only young people, with the great majority infected with the Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2, hence the generalizability to older age groups and other viral variants is uncertain.

And for those interested, patients included into the SARS-COV2 negative group were those who did not have anti-SARS-COV2 antibodies based on blood samples:

When it comes to the results, the researchers note the prevalence of PCC and PIFS among those who were SARS-COV2 positive at baseline when compared to those who were negative.

Prasad summarizes it the following way:

The first question is how many kids had Post Covid Conditions (PCC)?

Covid group - 48.5%

No covid group 47.1%

Oooff, stone cold negative result. No significant difference;

Second question: how many kids have post-infective fatigue syndrome (PIFS)? The answer is 14.0% and 8.2%, and it is not significant.

COVID19 had nothing do with either of these two conditions.

Let’s me repeat that. Having had COVID19 had NOTHING TO DO with having symptoms consistent with “long covid.”

With the results being displayed in the supplementary material (among other places in the article as well):

Now, is this a shut case of “no difference"?

Many issues plague Long COVID, and really make the quantitation of Long COVID extremely difficult.

Take, for instance, that the WHO criteria for PCC is extremely broad (emphasis mine):

1.7. Caseness assessment The wording of the WHO diagnostic definition of post-COVID-19 condition (the term used by the WHO for long COVID)14 as well as the international criteria for the diagnosis of PIFS15 were scrutinized in order to establish operationalised definitions based upon available data in the LoTECA project. As a general approach, questionnaire data on clinical symptoms and functional disability were used to define potential cases, whereas other questionnaire data as well as clinical and laboratory findings were used to identify possible exclusionary criteria. Potential cases without possible exclusionary criteria were classified as ‘certain cases’, while for cases with possible exclusionary criteria were further scrutinized by two researchers independently and blinded for initial SARS-CoV-2 status, and eventually labelled “uncertain cases” if classification remained uncertain. The processes are outlined in detail below and in Figures S1 and S2.

For the WHO case definition of long COVID, a list of 13 clinical symptoms found to be persistently prevalent among COVID19 sufferers in a large population-based Norwegian study guided the selection of questionnaire items used to screen for potential caseness. 37 Individuals reporting at least one of these symptoms 1-2 times a week or more were considered to fulfil the persistent symptom requirement of the WHO definition of long COVID.

Thus, a case/noncase assessment of PCC appears to depend on fitting at least one persistent symptom. When given such comments such as “experienced cough” a huge degree of subjectivity will be introduced.

Remember that these surveys were not conducted on a monthly basis post-infection, but were provided in a questionnaire 6 months post-recruitment and thus would require recall of these symptoms, leaving a serious degree of subjectivity in responses.

This is, unfortunately, a serious issue that has plagued nearly all Long COVID studies- the group that is intended to be measured is so broad and ambiguous that nearly all studies on Long COVID will capture comparable values in both positive and negative groups.

That is to say, many studies may not be able to overcome background noise as symptoms of PCC may be extremely common in the general public, which the researchers have commented on:

Hence, mild acute COVID-19 per se does not seem to be the main driver of most persistent symptoms in this age group. Rather, 2 other phenomena might be affecting these results: first, symptoms associated with PCC are common in the general population. For instance, the point prevalence of fatigue was reported to be 34% to 38% among British adolescents,35 with similar high rates for symptoms such as dyspnea and memory problems.3

Note here that mild acute COVID is mentioned.

But this doesn’t mean that information provided may not be fruitful.

In contrast to symptoms of PCC note that PIFS symptoms meet a much stricter criteria:

Keep in mind that PCC and PIFS are not entirely comparable, but the stricter criteria for PIFS also comes with a wider difference in reported cases with respect to SARS-COV2 positive and negative patients.

Although Dr. Prasad argues that these values are not significant, one can also raise the point that a difference between 1.4% and 5.8% with respect to PCC and PIFS may provide a way of contextualizing these results, in that more strict criteria of post-COVID symptoms appear to note a greater discrepancy between positive and control groups and a greater ability to assess actual post-COVID symptoms.

Unfortunately, such an argument is one that is based on highly subjective data.

Remember, again, that these reports were based on questionnaires. I recall an adage from one of my college psychology courses:

Those who answer questionnaires are usually not the people you want answering questionnaires.

I’m not sure how well this actually holds up, but consider that these questionnaires may suffer from a sampling bias antithetical to a healthy bias. Instead, here there’s likely to be an unhealthy bias, in that those who are unhealthy or suffering from something may be more inclined to sign up for such studies as the one cited here.

Dr. Prasad also suggests the same in his post:

The cohort is well matched at baseline, and these kids were all selected because they sought PCR testing for COVID19. Ergo, many may have felt sick, and some of the people sick were sick with covid while others were sick with something else. This is similar to another paper on the topic that I discuss in this video.

And so such a study is likely to capture people with PCC-like symptoms in both the positive and negative group, again adding to the issue of overcoming the noise burden:

A limitation to external validity, shared with similar studies in nonhospitalized individuals, is that our study was prone to self-selection bias. We cannot rule out that our sample was skewed with regards to what we have described as indirect stressors, ie, that individuals who chose to enroll in the control group had more symptoms than the background population.

Long COVID, Semantics, and Treading Carefully

I will reiterate the point once again that many Long COVID studies suffer from severe degrees of ambiguity and subjectivity, making it hard to consider these evidence fruitful in either inferring or refuting Long COVID.

However, that doesn’t mean that Long COVID doesn’t exist, or is just a construct as several have argued.

Rather, it suggests that no study may fully quantify the actual degree of Long COVID going on in the general public.

But the crux of much of the COVID and vaccine arguments aren’t dependent on a relative answer, but really that policies that remove bodily autonomy and enforce measures that have not been shown to be effective are policies that should be fought against.

When detailing myocarditis relativism in the above post I made the point of suggesting that the argument has never been about what produces fewer cases of myocarditis, but that a vaccine considered to be “safe and effective” probably should not be leading to any cases of myocarditis:

Myocarditis can occur in those who are infected with COVID as well as those who get vaccinated. One does not need to concede one argument in order validate another. In fact, one should probably argue that a “safe and effective” vaccine shouldn’t come with any cases of myocarditis, full stop.

An argument about a vaccine that provides some protection against SARS-COV2 does not inherently argue that vaccine mandates should be enforced.

Both ideas can feasibly exist, and in fact a measure of critical thinking requires that one be able to parse information in a reasonable manner rather than commit to an idea of denialism if it removes the burden of supposed cognitive dissonance or mental strain.

Thus, one can argue the existence of Long COVID while also saying that policies that enforce vaccination or masking due to Long COVID risk are entirely unethical due to autonomy and immoral coercion rather than a game of Long COVID relativism.

One can argue that Long COVID may be overexaggerated while also making the point that there are those who are legitimately suffering from such a malady (note here that I don’t believe that this is what Dr. Prasad is doing, but something I see occurring often in other circles).

I will end this post with one more point. It’s quite clear that the ambiguity in defining Long COVID makes room for many forms of interpretations, including how Long COVID compares with respect to other post-viral syndromes or sequalae.

Personally, I’ve never argued Long COVID in a comparative manner to other post-viral syndromes. In fact, it was the question of Long COVID that has shown that research into post-viral syndrome has been severely lacking, leaving a huge gap in the literature that some may use to argue towards Long COVID denialism.

Many months ago when I was researching into Long COVID I came across the fact that post-viral syndrome, including chronic fatigue syndrome, generally presented in women and may have been a driver for the lack of studies.

It was this presentation that lead to hesitancy in diagnosing post-viral syndrome as a real disease, with many doctors arguing that post-viral syndrome is likely a reflection of hysteria and other psychological issues.

For instance, an editorial from 19882 commented that symptoms of post-viral syndrome may be partially of viral etiology as well as hysteria:

And this from a time in which may readers of this Substack were likely to have been born, noting that not much may have changed in the past few decades.

I bring up this point because the Selvakumar, et al. study notes a bias towards female sex as a predisposition for either FCC or FIFS:

Although not considered statistically significant, the fact that such a result has stood out raises questions as to why there may be a bias in female sex towards these symptoms, similar to those women who may have experienced post-viral syndrome and had their conditions not taken seriously for, well, being a woman.

It’s here that I tread lightly in immediately suggestion a psychological factor as an explanation for these symptoms rather than one of viral etiology.

In the same ways that the field of post-viral syndrome may have been stunted due to these symptoms appearing predominately in women, we should be careful in making assumptions which may otherwise hinder finding evidence if the evidence appears to occur more in one sex.

Note here that the researchers don’t suggest that Long COVID isn’t occurring, but the definition used by the WHO may have serious issues, and that symptoms contributed to psychosocial issues may be related to Long COVID (emphasis mine):

The 6-month point prevalence of PCC was similar in infected and noninfected individuals, thus questioning the usefulness of the WHO case definition. Symptom severity at baseline was the main risk factor, and correlated with personality traits. Low physical activity and loneliness were also associated with the outcome. These results suggest that factors often labeled as psychosocial should be considered risk factors for persistent symptoms. This does not imply that PCC is “all in the mind,” or that the condition has a homogeneous, psychological etiology. Rather, there might be heterogeneous biological, psychological, and social factors engaged in triggering and maintaining the symptoms of the individual.50 However, the results do suggest that nonpharmacological interventions may be beneficial and should be investigated in future studies, in line with experiences from PIFS following other infections.51

So I may disagree on what this study actually offers (i.e. these studies really can’t provide anything meaningful one way or another), but I can agree on what Dr. Prasad remarks on at the end of his post:

And the article should say: All kids will get COVID19 soon. There are few data to support vaccinating health kids. We should let parents decide, and keep quiet, and in the meantime, learn to never restrict kids lives again.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Selvakumar J, Havdal LB, Drevvatne M, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics Associated With Post–COVID-19 Condition Among Nonhospitalized Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e235763. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5763

Archer M. I. (1987). The post-viral syndrome: a review. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 37(298), 212–214.

For those who prefer a video Dr. Prasad actually went over the study for those interested:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZspGfen11E

Also, something that I did not mention that is pretty critical is that the measure for PCC is so loose that you're essentially not accounting for the symptoms in question and really just shuffling people on the basis of COVID positivity.

For instance, the COVID negative group may be comprised of a large portion of people who record dizziness or a cough at some point throughout the week and be considered a case of PCC sans a COVID infection. However, if someone were to get additional symptoms, such as loss of smell/taste and or shortness of breath along with the other typical symptoms you'll still be counted in the same way as someone with just an occasional cough. There's no measure of "more PCC" in this study and so you can't differentiate based on multiple symptoms.

Hopefully that adds more context.

I am very torn on Long Covid.

I firmly believe in its existence as I know several people who have/had it.

On the other hand, LC has not been researched properly. It was not even defined, not even subsets of it.

Most research was cheap surveys and such. Very little investigative lab work, little attempts to define it etc.

What attempts are made to quantify it, they always come up with lower prevalences.