FDA approves Wegovy in reducing risk of cardiovascular-related events

The new indication of use suggests a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease based on one study with some strange data.

Last Friday the FDA gave approval to label GLP-1 RA Wegovy as helping to reduce serious cardiovascular events.

This tacks on another alleged benefit for these drug, and thus further spurs greater interest as the market for these drugs continues to boom. More importantly, it now captures another demographic (those with cardiovascular disease) to which these medications can be prescribed to. Again, the incentives for these drugs continue to grow, leading to articles such as the one below to be released:

All this excitement stems from only one clinical study published in NEJM1 in mid-December called the Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People with Overweight or Obesity trial, or better known as the SELECT trial.

In essence, the clinical trial which included over 17,000 patients is argued to show that those who were prescribed Wegovy at the highest dose of 2.4 mg Semaglutide weekly appeared to have a reduction in major acute cardiovascular events (MACE) by about 20%, leading to further increased interest within this class of drugs.

Now, prior to the release of SELECT I covered a previous clinical trial called SUSTAIN-6 which had similar methodologies as SELECT but fewer participants and had both stratified and placebo groups. Readers can look at that article for some of the study outlines and pitfalls that were noticed with SUSTAIN-6.

A new marketing ploy for "weight-loss drugs"?

Edit 8.12.2023: The caption for Supplemental Figure S4 A originally stated 1.0 mg placebo when it should have stated 0.5 mg placebo when referring to the discrepant plot line. A correction has been m…

Because of these similarities in methodology, I won’t go into too much detail regarding SELECT. Note that SELECT skews relatively older (mean age of participants around 62), were predominately male (over 70%), had high BMI’s (low-mid 30s), and generally had a prior history of a cardiovascular event, with a nonfatal myocardial infarction (heart attack) being the predominate event2:

Patients appeared to be properly matched across the characteristics listed. Among those who were prescribed Wegovy a gradual increase in dosing occurred starting with 0.24 mg Semaglutide weekly until patients reached the final dose of 2.4 mg:

The starting dose of semaglutide was 0.24 mg once weekly, and the dose was increased every 4 weeks (to onceweekly doses of 0.5, 1.0, 1.7, and 2.4 mg) until the target dose of 2.4 mg was reached after 16 weeks.

Note that any adverse effect at higher doses led to a more gradual increase in dosage, and that some patients were able to stay at a dosage lower than 2.4 mg weekly as well. It appears that around 77% of Wegovy patients reached the 2.4 mg dosage by the 104-week mark in the study.

Results (and more strange plots)

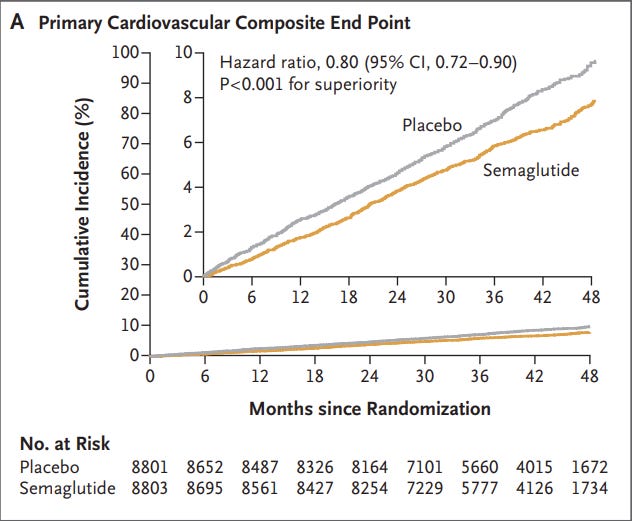

When looking at the primary endpoint of any cardiovascular event the Wegovy group appears to show a marked decline. Note that the primary endpoint is a composite value considering cardiovascular-related deaths, nonfatal heart attacks, and nonfatal strokes:

Upon first glance this may seem like a very good benefit. It would at least suggest the use of Wegovy may help to reduce cardiovascular-related events by around 20%. However, like the SUSTAIN-6 trial there are a few issues worth noting that makes these results rather complicated to assess.

For one, note that the Wegovy group appeared to show a decline in weight of around 9% original bodyweight whereas the placebo group showed an average weight decline below 1%:

The participants were on average close to 100 kg in each group, meaning that a near 9% weight loss would be close to 20 pounds lost.

Because obesity is related to greater risk of cardiovascular disease one can assume that any weight-loss may help to reduce the risk of a cardiovascular event. In this case, it begs the question if the reduced cardiovascular events within the treatment group may just be a consequence of the weight-loss.

If so, that also begs the question if a medication would be needed in the first place. The study itself doesn’t make mention of the exercise or diets of the participants, and therefore we don’t know if any behavioral changes or lifestyle changes may have occurred during the inclusion into the study. Like SUSTAIN-6 these sorts of studies don’t/can’t separate effects from weight-loss or biochemical/pharmacological effects tied directly to the drug.

What’s also interesting is that the study itself seems to mask some strange occurrences through composite analysis.

For instance, when looking at Figure 1A there’s an obvious gradual separation between the line for the placebo group and the one for the Wegovy group that widens over time, suggesting that the rate of MACE among the placebo group is higher relative to the Wegovy group.

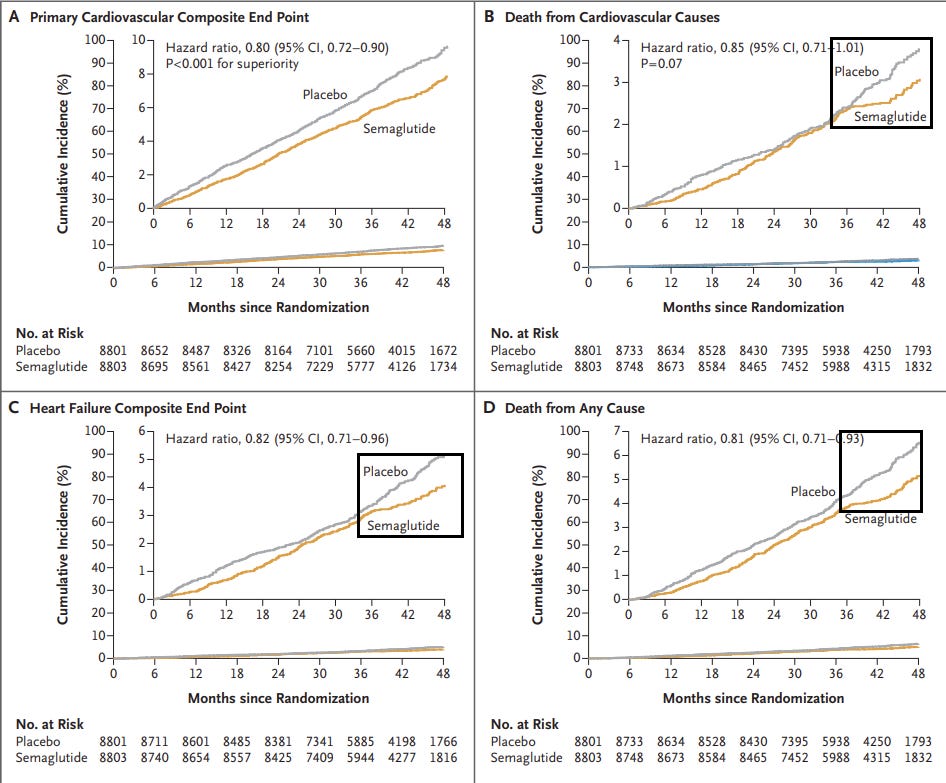

However, when examining the plots separately notice that there is a sudden abrupt change within the last few months (from 36-48 months).

The study complicates much of its numbers, switching between weeks and months at various points.

Note that mean duration of exposure was 33 months for Semaglutide and 35 months for placebo with the mean patient follow-up being near 40 months. There’s a necessary question to consider regarding how many patients continued to be prescribed Wegovy and how many patients were provided placebo.

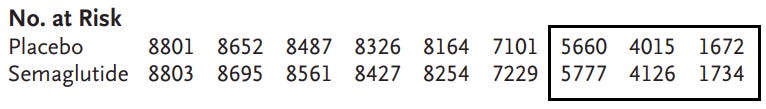

But what’s important to note here is that the 36-month timepoint onward is essentially a jumping off point, in which participants may have halted their inclusion, may have gotten lost to follow-up, etc.

Essentially, at the 36-month mark it’s likely that a lot of scrambling in patient characteristics may have occurred during the 36-month timepoint and onward as patients continued to drop out.

Note that a drastic decline in the number of participants occurs during this time when looking at the number of at-risk participants:

The study seems to only use the 48-month follow-up assessments as the last timepoint because too many participants dropped out or were lost to follow-up afterwards to make calculations.

It’s likely that patients may have still been properly matched between the two groups, but it nonetheless raises questions of whether the patients lost to follow-up may have biased the cardiovascular events to appear higher among the placebo groups. How many participants continued to take Wegovy during follow-up, and how many who did not return for follow-up would still have a cardiovascular event but not be included in the study?

What’s strange is that the rate of cumulative cardiovascular-related deaths and heart failure (Figure 1B and 1C, respectively) are rather similar between the two groups between the 24–36-month mark. It’s the pairing of the relatively similar lines which suddenly change at the 36-month mark that warrants questioning what may have happened during that timeframe.

And although the study mentions the post 36-month mark as being the follow-up period note that primary and secondary endpoints were calculated based on the time from enrollment until time of last-follow up as mentioned in the footnote for Table 2:

Data are for the full analysis population during the in-trial observation period (from randomization to the final follow-up visit). All end points were analyzed with the use of a Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as a categorical fixed factor. Data from patients without events of interest were censored at the end of their in-trial period. NA denotes not applicable.

Bear in mind that heart failure and death from any cause don’t appear to be factored into the composite primary endpoint.

Nonetheless, the language here would at least suggest that participant data was used for the calculations so long as participants continued to appear for follow-up. Again, what this would suggest (in a hypothetical sense) is that if a participant stopped appearing for follow-ups after the 36-month follow-up but had a cardiovascular event around the 40th month since trial inclusion, they likely wouldn’t be included within the final calculations irrespective of whether they were within the placebo or the Wegovy group. On the other hand, someone who continues showing up for follow-ups may report their cardiovascular events and thus be included in the calculations.

Again, what exactly is happening near the end of the study?

Overall, this at least suggests that an explanation should be provided for how the results from the tail-end of the study may have affected the calculated hazard ratios. Some information may be found from the Supplementary Appendix but as of now I haven’t been able to gain access to this portion. It’s curious if the placebo patients who continued follow-up were more prone to cardiovascular events or were more likely to report their cardiovascular events to researchers.

If anyone has any thoughts on what may be going on please feel free to ask, but for all intents and purposes it just seems rather strange for the trend to change so drastically, especially during the follow-up period.

In Addition…

There are a few other things worth noting regarding this SELECT study.

Additionally, note that dropout due to adverse effects were higher among the Wegovy group, predominately due to gastrointestinal issues related to Wegovy:

Adverse events leading to permanent discontinuation of semaglutide or placebo occurred in 1461 patients (16.6%) in the semaglutide group and 718 patients (8.2%) in the placebo group (P<0.001); these events included gastrointestinal disorders in 880 patients (10.0%) in the semaglutide group and 172 patients (2.0%) in the placebo group (P<0.001). Gallbladder-related disorders occurred in 246 patients (2.8%) and 203 patients (2.3%), respectively (P=0.04).

It’s curious how this may have affected the endpoints of this study, and it also follows a pattern seen with other studies and real-world anecdotes regarding the GI issues related with this drug. So even though the authors argue a cardiovascular benefit with the use of Wegovy note that there may be a risk of possible adverse events, especially if one considers a dose-related risk of adverse events.

Following along, note that Wegovy is the highest dose of Semaglutide available. This raises a question if the cardiovascular benefits may be seen only at higher doses of the drug. This may run the risk of providing a stronger dose of a drug of which there is no longterm safety data that also carries serious risks. Note that the actual dose may be inconsistent in this study depending on if a participant experiences an adverse effect.

Note that the argued reduction is only around 20%. This may be considered a rather significant number, but it also may not mean much given the possible risk of side effects, cost, and adherence to treatment for patients that come along with these medications. There’s a real question regarding how much this reduction will actually translate into better patient outcomes, and how many clinicians will properly balance risk and benefit.

Unlike SUSTAIN-6 the authors don’t provide a plot for nonfatal heart attacks and nonfatal strokes even though they are included within the primary endpoint. Again, this may be in the Supplementary Index but it’s strange that no plots are shown for these two measures.

The units used in this study are also rather unorganized. This may be typical of studies, but it makes it difficult for readers to consider the actual timeline of events. For instance number of people taking the full 2.4 mg of Semaglutide was based on the 104 week (24 month/2 year) mark. This doesn’t tell us what dose patients were taking after the 104-week mark and whether some patients moved to lower doses, which itself raises problems as it may skew the rate of adverse events and interpretations of the endpoints. So the study references various numbers but taken from different timepoints, making the data more difficult to connect together.

For Thought

Many of my thoughts I outlined in the SUSTAIN-6 article are pertinent here so I won’t rehash them again.

That being said, as these medications continue to see more generalized use there should also be a growing concern regarding the need for these medications, and whether there will be any off-ramp- will people be able to stop taking these medications at some point?

But more importantly we should be asking the question of what is happening to native GLP-1. What exactly is happening within the body of these people that an exogenous mimic of an incretin hormone can have such strong effects on the body? Are obese, unhealthy individuals not producing GLP-1 for some reason, and what would that reason be? Do people become tolerant of GLP-1? How much does diet, the microbiome, and other environmental factors affect our production of GLP-1? And why is it that discussion around GLP-1 RAs never seems to also include many of the questions listed above?

It’s as if we are forgetting that we produce these hormones ourselves, because if we produce these hormones ourselves we probably wouldn’t need to rely on exogenous mimics.

This is something that may be explored at a future date. The next article will try to address another factor regarding the effects of GLP-1. That is, the reduction of cardiovascular-related events from taking GLP-1 RAs may not be related to weight loss alone, but may also be related to the agonistic effects these drugs have on the heart and the endothelium, as GLP-1 receptors seem to be found all throughout the body.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Lincoff, A. M., Brown-Frandsen, K., Colhoun, H. M., Deanfield, J., Emerson, S. S., Esbjerg, S., Hardt-Lindberg, S., Hovingh, G. K., Kahn, S. E., Kushner, R. F., Lingvay, I., Oral, T. K., Michelsen, M. M., Plutzky, J., Tornøe, C. W., Ryan, D. H., & SELECT Trial Investigators (2023). Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine, 389(24), 2221–2232. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307563

These demographic data appear to be similar to the SUSTAIN-6 trial.

Ozempic and Wygovy are hugely popular drugs. Our society has become more obese with all of the accompanying conditions: heart disease, diabetes, etc. It's VERY DIFFICULT, almost impossible, to lose weight with the average American diet featuring high carbohydrate, high sugar, high salt processed foods which are quite addictive. A ketogenic diet with intermittent fasting might be successful and should be tried BEFORE surgery and drugs, the medically approved and patient preferred way of providing a quick fix. Declaring Wygovy effective for heart conditions allows it to be more easily covered by insurance. This is a win/win solution that is beneficial for everyone--except for the patients' health.