A new marketing ploy for "weight-loss drugs"?

A recent clinical trial for Wegovy suggests that use of this GLP-1 RA may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, but is there more to the story? And a retrospective look at an older study.

Edit 8.12.2023: The caption for Supplemental Figure S4 A originally stated 1.0 mg placebo when it should have stated 0.5 mg placebo when referring to the discrepant plot line. A correction has been made.

As I mentioned on Tuesday the stock prices of pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk seemed to have increased dramatically after news of a recent clinical trial suggests that Wegovy, a higher dose drug utilizing the peptide hormone Semaglutide may reduce risk of cardiovascular disease.

Novo Nordisk has yet to release the results of this clinical trial although their press release made mention of this in regards to the study named SELECT:

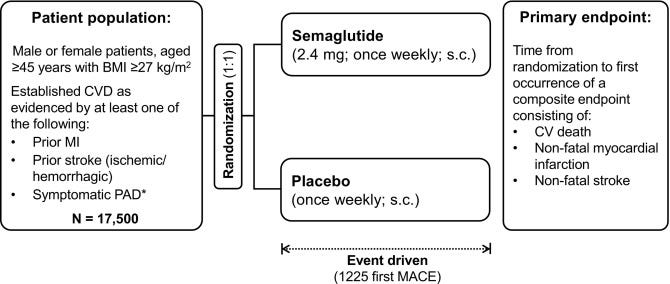

SELECT was a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo as an adjunct to standard of care for prevention of MACE in people with established CVD with overweight or obesity with no prior history of diabetes. People included in the trial were aged ≥45 years with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2.

The primary objective of the SELECT trial was to demonstrate superiority of semaglutide 2.4 mg compared to placebo with respect to reducing the incidence of three-point MACE consisting of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke. Key secondary objectives were to compare the effects of semaglutide 2.4 mg to placebo with regards to mortality, cardiovascular risk factors, glucose metabolism, body weight and renal function.

The trial enrolled 17,604 adults and has been conducted in 41 countries at more than 800 investigator sites. The SELECT trial was initiated in 2018.

The initial results suggest a statistically significant reduction of major acute cardiovascular events (MACE) of around 20% in those who were given Wegovy relative to placebo.

With such news gaining traction many people have raised a question of whether these GLP-1 RAs may see even further, broader use than just for use in Type II diabetes or weight loss, likely increasing public interest and want of these drugs even more than we are seeing now as can be seen with the stock price spikes.

Even Nature has jumped onto the GLP-1 RA bandwagon with an article published yesterday:

The article goes on to suggest that these findings may change the face of preventative medicine when it comes to cardiovascular disease:

Researchers say the findings, if confirmed, could change the practice of preventive cardiology. The results also suggest that the new generation of anti-obesity drugs can profoundly improve health, not just reduce weight. “This is probably the most important study in my field in the last ten years,” says Michael Blaha, director of clinical research at the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Baltimore, Maryland. ”It gets to that cardiometabolic risk that’s been difficult to treat in practice.”

”It's hard to think of other [drugs], apart from statins, that have shown such a profound effect,” says Martha Gulati, director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California.

All of this sounds rather remarkable, but is all that Semaglutide’s gold?

One immediate response to this may be rather obvious- if these drugs lead to weight loss, can’t the reduced risk of cardiovascular disease be attributed to the weight loss caused by the drug and not necessarily some tangential mechanism of action?

Unlike what many in the body positivity movement may argue it’s been heavily (no pun intended!) established that obesity is associated with increased risk of a multitude of diseases, including cardiovascular disease.

So is all of this news compelling, or a bit obvious to those who spend a bit of time connecting dots?

In some ways this news may consequently disrupt how we view health. Rather than view health from the perspective of weight management and health/lifestyle choices, many people may be inclined to infer that their health is outside of their own control, making them feel as if they need these sorts of drugs. Now, not only will these drugs be marketed for weight loss, but now likely for cardiovascular disease and other maladies that may just be solved with eating better and losing weight in general.

And so it appears more and more that we are removing ourselves from the path of first principles in health more towards medicalization.

We’ll have to wait and see what exactly occurred in the SELECT trial, but given that Novo Nordisk has already conducted similar trials we may have some precedent set already.

When looking up information on this SELECT trial I came across this other trial, which I initially mistook as being the SELECT one.

This trial, labeled the SUSTAIN 6 trial, has a similar outline has SELECT. However, this trial was conducted several years back with recruitment starting in 2012 and ending around 2018. The article published in NEJM, although appearing rather new, was actually published in 2016.

It’s likely that this study flew under the radar since interest in these drugs weren’t at the same levels at they are now. Nonetheless, this study may provide us with some insights into SELECT and whether these recent findings are all that they appear to be.

Retrospectively Examining SUSTAIN 6

Although SUSTAIN 6 is a bit similar to SELECT there are a few noticeable differences.

For instance, the study group was far smaller for SUSTAIN 6 with the overall number of participants being a little over 2700 relative to SELECT having over 17,000 participants. SUSTAIN 6 also only went on for about 2 years in contrast to SELECT’s 5 year study timeline.

The timing of the study seems to suggest that SELECT is piggybacking off of the results from SUSTAIN 6 given the endpoint of SUSTAIN 6 and the starting point of SELECT being 2018.

Additional differences include the average age of SUSTAIN 6 patients being around 65, although the recruitment age cutoff was around 50. This means that although SELECT has a cutoff age of 45 it’s likely that the actual patient demographic may average several decades older. Again, we’ll have to see what SELECT’s demographics are when the data is released.

Unlike SELECT, and probably the most important thing to point out, SUSTAIN 6 stratified their placebo and Semaglutide groups. For instance, the Semaglutide group was separated into either a 0.5 mg group or a 1.0 mg group. Placebo groups were stratified in a similar way. SELECT, at least as it appears from the press release, only seems to have used a placebo group and a Wegovy group.

Now, this is important for a few reasons.

Note that Semaglutide is provided in stratified dosing regimens. That is, patients are given 0.25 mg starting doses of Semaglutide in order to allow the body to tolerate this drug. After 4 weeks patients are then given a higher dosage of 0.5 mg. Patients are then maintained on a 0.5 mg regimen unless their sugar levels don’t improve, in which case they are given higher doses of either 1 mg or 2 mg Semaglutide.

Note that Wegovy, which was used in the SELECT trial, has the highest dosage of Semaglutide at 2.4 mg.

Given these different doses the immediate thought must be a dose-related effect, in which case the higher the dose the lower the risk of cardiovascular disease. This, again, may be tied to higher doses also likely producing greater weight loss.

However, the real question one should ask is whether these higher doses of 1 mg, 2 mg, or even Wegovy are actually commonly used.

That is, if these studies are focused on higher drug doses how likely is the average person going to be prescribed these higher doses? Or is the intent here to suggest that higher doses of Semaglutide are needed in order to see some sort of benefit, which may come with the increased risk of possible adverse events?

So when looking at these studies consider that they may not be indicative of those who are given these sorts of drugs.

Now, in looking at the Sustain 6 trial what’s interesting is that this trial was powered based on the trial being a noninferiority trial. When we look at clinical trials we are generally looking at them as superiority trials. That is, does the treatment work better than placebo or some other standard? The SELECT trial, for instance, is designed as a superiority trial relative to placebo.

A noninferiority trial is slightly different. Instead, a noninferiority trial is designed in such a way that it argues that the treatment isn’t worse than the active control, which is usually a standard treatment.1

Now, there’s a lot to statistics and trial design that I am unaware of. However, it appears that there may be some issues with this study being designed as a noninferiority study as the control used is a placebo, as well as the limited sample size.

Marso, et al. makes the following comment about the use of a noninferiority study for SUSTAIN 6:

This trial was powered as a noninferiority study to exclude a preapproval safety margin of 1.8 set by the Food and Drug Administration. It was not powered to show superiority, so such testing was not prespecified. However, the treatment effect of semaglutide and the accrual of more events than estimated resulted in a significantly lower risk of the primary outcome among patients in the semaglutide group.

This may not mean much in the long run, but it’s worth pointing out that this study doesn’t follow typical study designs and that may influence the results given the differences in statistical analysis.

Study Results

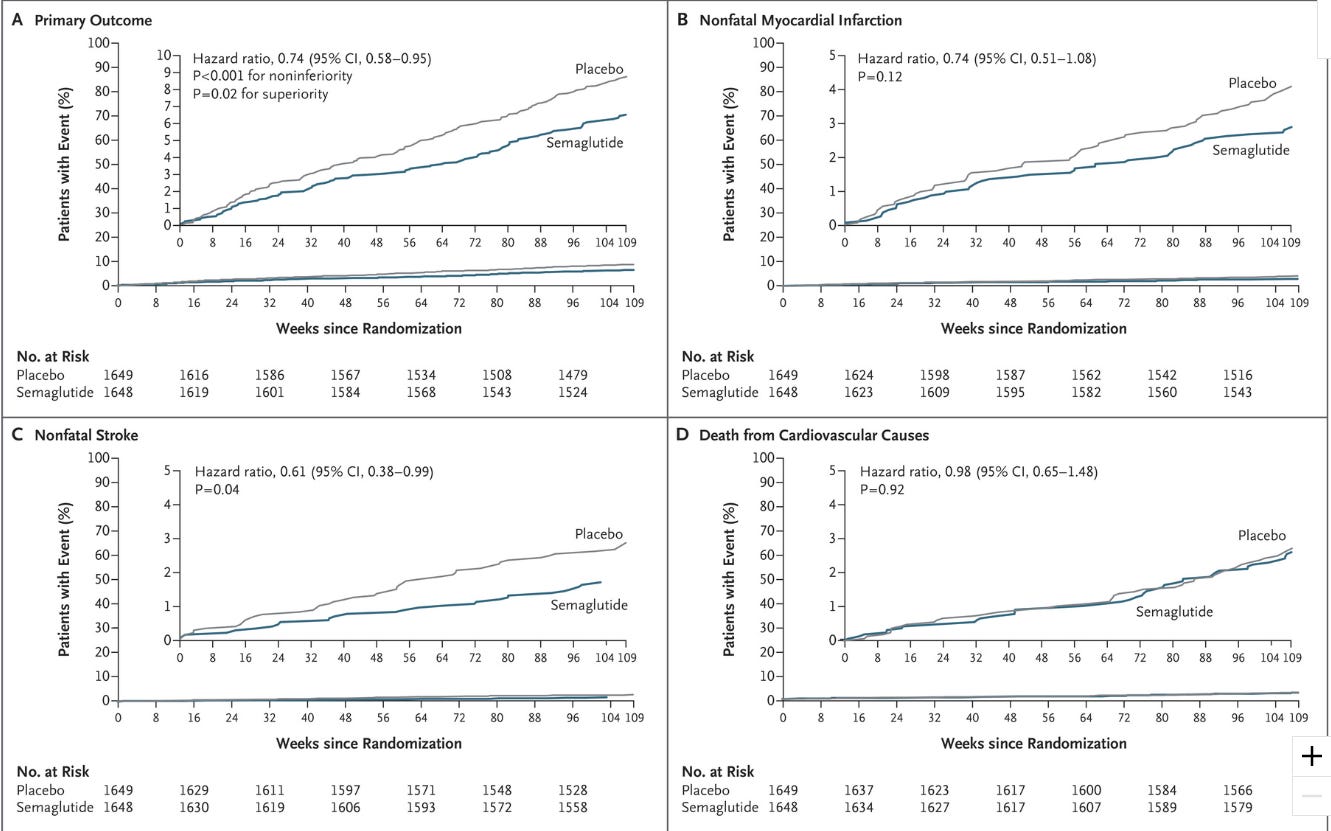

I’ll leave some of the finer details of the study for the NEJM article2 so please refer to that. As it stands, the SUSTAIN 6 study seems to suggest a cardiovascular benefit from Semaglutide relative to placebo when looking at composite scores (i.e. subgroups for Semaglutide and placebo are clumped together).

The primary outcome of this study was to examine cadiovascular-related deaths, nonfatal strokes, and nonfatal heart attacks. Interestingly, the reports here seem somewhat better than SELECT’s initial reports:

Semaglutide-treated patients had a significant 26% lower risk of the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke than did those receiving placebo. This lower risk was principally driven by a significant (39%) decrease in the rate of nonfatal stroke and a nonsignificant (26%) decrease in nonfatal myocardial infarction, with no significant difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. Similar risk reductions were observed with both doses of semaglutide.

So here a reduced risk of around 26% was seen relative to SELECT’s initial reporting of 20% after 5 years.

Again, remember that this is a composite score. When mapped using Kaplan–Meier plots the rate of events across the different primary outcomes can be seen as such:

Remember that the slope of these graphs are dictated by the number of events that occurred within each group.

To reiterate, the question we should be asking is whether this data shows an actual benefit, or whether there may be more going on.

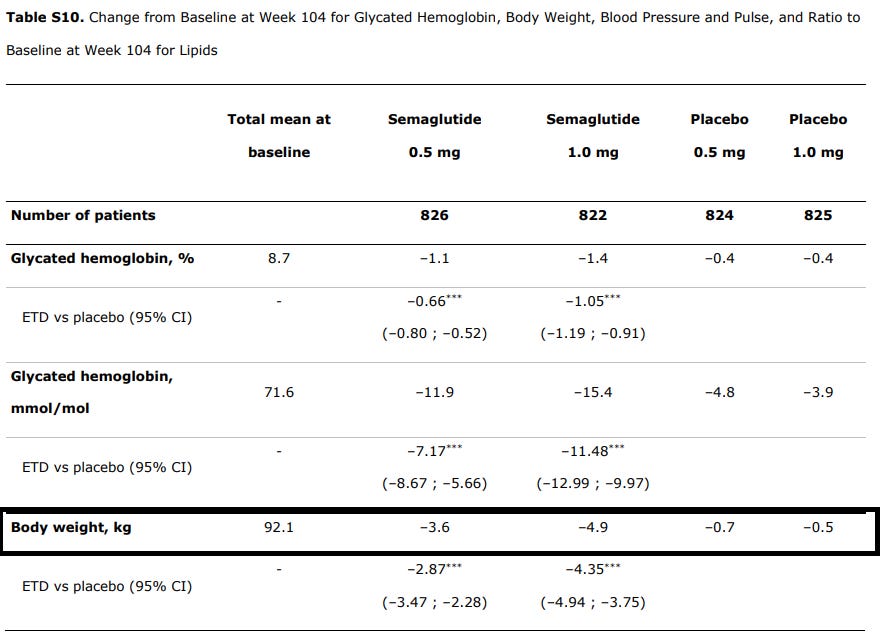

Remember that these drugs have been argued to increase weight loss, which itself can lead to better cardiovascular outcomes. In this case there were greater levels of weight loss within the Semaglutide group relative to the placebos:

For those of us who use lbs that’s a little over 10 lbs for the highest dose Semaglutide group compared to around 1 lb for the highest placebo group. This isn’t much of a weight difference, although any loss of excess weight will have some inherent benefit in health.

The authors suggest that the weight loss may have contributed to the reduced risk:

Clinically meaningful and sustained weight loss and a reduction in systolic blood pressure occurred in the semaglutide group versus the placebo group over 2 years. The reductions in glycated hemoglobin, body weight, and systolic blood pressure may all have contributed to the observed reduction in cardiovascular risk with semaglutide.

Regardless, it’s important to emphasize that any benefit from Semaglutide needs to be differentiate by any benefit that may come from weight loss and lifestyle choices in general. Given that these GLP-1 RAs are being examined for their effects on addictive behaviors it’s possible that decreases in cardiovascular risk among Semaglutide recipients may be due to changes in behaviors that make one more inclined towards unhealthiness. Remember that the participants in this trial are already those who are in poor health, and so this may just be a reflection of changing one’s poor habits for better habits.

Now, let’s look back at this compositing that the authors did with both the placebo and Semaglutide groups. Pay attention to how combining different outcomes together than influence results. If you look Figure 1 there seems to be a large discrepancy in primary outcomes between the two groups. Primary outcomes are a collection of nonfatal strokes, nonfatal heart attacks, and deaths related to cardiovascular complications.

Thus, the effect here is driven by each individual outcome. We can see that cardiovascular-related deaths were comparable between the two groups, and the authors’ comments make it appear as if these outcomes are driven by the incidences of nonfatal strokes:

This lower risk was principally driven by a significant (39%) decrease in the rate of nonfatal stroke and a nonsignificant (26%) decrease in nonfatal myocardial infarction, with no significant difference in the rate of cardiovascular death.

However, the Supplemental Figures provide some more insights when the data is stratified based on doses. Although I wouldn’t say they are comparable, the major outlier in this graph appears to be the 0.5 mg placebo group which deviates from the other subgroups:

So it’s not necessarily that the results are driven by Semaglutide’s benefit, but rather it’s possible that the results are driven by this strangely higher rate of nonfatal strokes occurring within the 0.5 mg placebo group. Keep in mind that, for all intents and purposes, both placebo groups should be comparable to one another in their trends and outcomes, so this deviation shouldn’t be occurring.3 Keep in mind that primary outcomes between the Semaglutide and placebo groups appear to be driven by nonfatal stroke outcomes, and so with this questionable data one would be particular about the overall reduction in cardiovascular risk for Semaglutide.

In contrast, there appears to be higher rates of nonfatal heart attacks among the 1 mg placebo group, with the 0.5 mg placebo group being comparable to the 0.5 Semaglutide group:

So again, more wonkiness. It may mean that the lower dose of Semaglutide may not be beneficial, and so a higher dose may be necessary as seen with the formation of the SELECT trial, but again there seems to be more going on to the data than one would see when looking at composite data.

In looking at some of the correspondence4 for SUSTAIN 6 trial it appears that the placebo groups were given a far higher dose of insulin relative to the Semaglutide group. This may be partially due to Semaglutide helping in manage diabetes, but this also raises a possibility that insulin may increase the risk of adverse events including some of the primary outcomes (Cosmi, et al.):

In SUSTAIN-6, the use of insulin at trial entry was similar between the two groups. However, during the LEADER trial, the use of insulin was approximately two times higher in the placebo group than in the liraglutide group, and during SUSTAIN-6, the use of insulin was approximately three times higher in the placebo group than in the semaglutide group. The significantly greater use of insulin in the placebo groups in these two trials may, at least in part, explain the increase in the risk of death from any cause as well as the increase in the risks of heart failure, cardiovascular events, renal failure, and hypoglycemia in these two groups. Hazard ratios for these events associated with increased use of insulin range from 1.23 to 4.57, as shown in two cohort studies in primary care.3,4 Thus, we wonder whether the greater use of insulin in the placebo groups than in the liraglutide and semaglutide groups during these trials may have amplified the beneficial effects of liraglutide and semaglutide.

The authors reject this claim, but I think it at least leaves room once again for more questioning about how this trial was conducted and whether there may have been things that happened which led to the benefits seen.

What does this mean for Wegovy and cardiovascular risk?

We will have to wait to see what the SELECT trial entails, but given that SUSTAIN 6 appears to be the foundation for SELECT I’m a bit skeptical of the actual cardiovascular risk benefits of these drugs.5

One obvious thing to note is that all of these effects may just be tied to weight loss in general, and so any benefit seen with Semaglutide may just be benefits that would occur with or without the use of these drugs. Of course, drug makers wouldn’t like people to come to that conclusions, and hence why many people seem to be reporting on these benefits as if they provide some unique effect.

There’s also the fact that the stratified subgroup plots suggest that there may have been more going on with the groups used in the SUSTAIN 6 trial, even though demographics were matched across all subgroups.

The language from the Press Release, as well as the article on the study outline, suggests that no subgroups are used, and so any funny business that may appear from subgroup analyses may disappear with composite scoring. Given that SELECT is essentially comparing nothing to the highest dose of Semaglutide available, the results here may just be a big case of “no shit, Sherlock!” Anything may be better than nothing in helping reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

Given that more and more reports are coming out about adverse reactions including stomach paralysis with respect to these GLP-1 RAs we should be hesitant to believe all of the news coming out about these drugs. Although I did not mention it here, note that there was a higher rate of diabetic neuropathy occurring among Semaglutide recipients relative to placebo. The researchers appear to remark that these cases are rare, although I could also argue that any cases of nonfatal strokes or heart attacks were relatively rare across the study period. They can’t pick and choose when events are rare or not rare if it downplays the possible harms with these drugs.

And so we are now encroaching ever closer to this magical weight-loss pill (well, subcutaneous injection), and one that continuously seems to show more benefits with each passing day.

Regardless of whether one chooses to take these drugs remember that medicine shouldn’t obfuscate basic, first principles in health. If it comes out that all of these benefits are things that one can achieve on their own then why go through the medical route?

We are moving ever-more closer to a medicalization of everything under the sun, and so we should be more discerning and reticent about the constant medicalization.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Kishore, K., & Mahajan, R. (2020). Understanding Superiority, Noninferiority, and Equivalence for Clinical Trials. Indian dermatology online journal, 11(6), 890–894. https://doi.org/10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_130_20

Marso, S. P., Bain, S. C., Consoli, A., Eliaschewitz, F. G., Jódar, E., Leiter, L. A., Lingvay, I., Rosenstock, J., Seufert, J., Warren, M. L., Woo, V., Hansen, O., Holst, A. G., Pettersson, J., Vilsbøll, T., & SUSTAIN-6 Investigators (2016). Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine, 375(19), 1834–1844. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1607141

Hypothetically speaking, it’s not as if a higher dose of a placebo should show some reduced risk of strokes.

Cosmi, F., Laini, R., & Nicolucci, A. (2017). Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Correspondence The New England journal of medicine, 376(9), 890. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1615712

Note that this is the opinion of someone who is not a medical professional. Remember that this information is intended to be informative not prescriptive.

Also, there are risks to these drugs. An acquaintance of mine has lost a lot of weight and she told me that she's on one of these drugs. She also has had pancreatitis, her gallbladder removed and now has an infectious lung disease called MAC. No plans to stop taking the drug and now needs a tummy tuck.