Bad Science- COVID and risk of MACE

Journalists are running with misleading narratives that COVID can increase risks of heart attacks and strokes for years based on a new study.

This post has hit the too long; didn’t send point, so if you cannot read this post in your email please read in on the Substack app or the website. Thanks!

It’s become the modus operandi of those in the media to weaponize science as a means of stoking flames of fear. Rather than spend time to parse out results of new publications and contextualize their meaning the media finds it more fit to run away with any bit of fear mongering possible.

Over the past few years, and in more recent months, I have pointed out reasons why the media should not be trusted to disseminate science as many of these outlets seem more driven to report narratives and talking points than objective results, leaving readers to ironically be misinformed on what the actual findings of a study are.

And to be quite honest, a bit of “doing your own research” on the part of a reader can easily point out strong incongruency in what is being reported and what is stated in a study.

I can go on about the dangers science journalism has wrought on public perception of science, but we will be here all day.

That being said, for someone who is looking for a more nuanced examination of “science journalism done wrong” take a look at Brian Mowrey of Unglossed and his recent coverage of COVID vaccines and the narrative that they can protect against cardiovascular-related harms from COVID itself. He’s a lot better at contextualizing methodology and explaining many of the faults in how these studies are designed.

Now, for the sake of this article we will look at another recent article1 regarding cardiovascular harms and COVID.

A bombastic title, and not only that but one of the study’s authors is none other than Stanley Hazen who has been featured on this Substack before as his team at The Cleveland Clinic has been involved with trying to tie risk of MACE to many different compounds including the sugar alcohol xylitol, erythritol, and the B-vitamin niacin. I have raised many criticisms of these studies as they appear to be fishing expeditions to find anything that could be correlated with MACE. Not only that, but Hazen’s team itself has been awarded millions of dollars in NIH-funding to conduct this type of research:

Metabolomics and Science Racketeering?

This is a follow-up to yesterday’s post in which I look into Hazen’s research team and consider all of their findings in an overarching manner, as well as consider possible reasons for such research …

The study’s focus revolved around examining if individuals who were infected/hospitalized with SARS-COV2 were at more risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) in the proceeding months/years relative to those who didn’t get infected.

It’s worth noting that the literature seems to allege an increased risk of cardiovascular-related problems immediately following a bout with COVID, and Brian Mowrey also mentions such harms in his own coverage of a different study. These findings serve as the pretext for the current study, and for the sake of argument let’s suppose that this appears to be the case. I haven’t looked at the literature myself we will take this to be a given for this article.

Now, whenever we consider the possible harm of a pathogen or an agent, we must always view it from the context of relativity. That is, the default assumption we should take is to assume that not all pathogens will result in death or severe disease (unless otherwise noted), and not all therapeutics will be harmful/beneficial for everyone.

As I have mentioned many times the go-to phrase in pharmacology is to state that it’s the dosage that makes the poison or put another way that the context in which a pathogen or therapeutic is introduced matters.

So, if we see a study which suggests that COVID puts one at risk of cardiovascular disease we should examine how the authors can come to such a conclusion.

The authors utilized patient data from the UK Biobank- a reservoir of medical information for hundreds of thousands of patients. We’ve talked before that such a database can be good for population-related studies, but reliance on such a database can result in research focused on quantity over quality. That is, such databases may only result in correlative work rather than work that can provide greater evidence of causality.

In short, the authors examined patients who were confirmed positive for a SARS-COV2 infection by way of a positive PCR test or by meeting criteria for COVID hospitalization between the time periods of February 2020 and December 2020. Patients were recorded as having a MACE event if the event occurred after the 30-day post-infection period. Any patients who experienced a MACE incident within the 30-day post-infection period were excluded from the analysis. This appears to be, in part, due to other research recognizing the increased risk of MACE within this acute time frame- the authors were interested in long-term risk of MACE.

These individuals were compared to a larger control population who were not COVID positive.

It’s important to note that such a study design may be confounded by a shuffling effect. Obviously, people who become COVID positive shouldn’t be considered with the control cohort in this study. The authors mention that everyone who tested positive or were hospitalized after the December 2020 period had their information censored i.e. taken out of the analysis. This at least suggests that shuffling between COVID- and COVID+ groups was controlled, although this itself could influence the end results as they may still be counted within the analysis prior to an event. I am unsure to what degree of censoring is occurring, but one would expect that censoring of patient data up to the point of a COVID infection could obviously bias results- it’s removal of a data point that may influence the results of the COVID+ cohort. Take this in mind when considering possible nuanced issues regarding this study.

Now, rather than provide a deep dive into the study I will instead point out a few of my issues with how the study presents its information and what implications this study offers. I encourage readers to look at both the study and the Supplementary Material for themselves to see if there are other issues with this study or if there is something worth rebutting in my analysis.

What you show, and what you don’t

As Bret Weinstein has stated several times on his Darkhorse Podcast the Supplementary Section of a study is where the bodies are buried. As in, sometimes if there is something that may raise suspicions regarding your findings you may want to hide them away in a place no one will really check- it’s the secret, naughty drawer of scientists who don’t want anyone to do more than a superficial degree of sleuthing.

We can consider this within the context of the following figure. The figure separates patients from the hospitalized COVID+ cohort as well as those within the COVID- cohort based upon their prior recorded history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). This is where we get the “money shot” and all of these bombastic headlines:

We can see here that those who were hospitalized with COVID who also had a history of cardiovascular disease (filled red line) saw a huge increase in MACE incidences within the following months. This isn’t too surprising all things considered, but it is worth noting that this group was already small to begin with and thus any incident of MACE would lead to a relatively large percentage increase on the graph.

Instead, the big shocker is the boxed region above and the convergence of MACE incidences between those who were COVID+ with no cardiovascular disease (dashed red line) and those who have cardiovascular disease and were COVID-.

It’s from this convergence that the authors are alleging a similar risk of a MACE incident as those who have cardiovascular disease, which is also further affirmed by subanalysis such as in Figure 3 (not shown here).

This would all seem rather alarming, and again given the context that there does appear to be a risk of developing MACE post-COVID such a finding would raise serious public health concerns as is being propagated by the media.

But hopefully readers can see an issue in some of this interpretation. Note that the incidences of MACE seem to occur predominately within the first few months following an infection followed by a tapering of such incidences. It may be a bit of a stretch to suggest that this would imply a risk of developing MACE years down the line, especially given that many participants were not included within the later portion of the analysis, likely because that would require having patients who got sick very early on in the pandemic.

Once more, if you compare the left graph with the right graph, you notice that the “convergence” disappears once patients are propensity-score matched. This means that when patients within the hospitalized COVID group were matched demographically to those within the population control group on medical history, age, sex, and educational background the convergence isn’t as robust, and in fact by the 1003-day mark more incidences of MACE occurred within the group with cardiovascular disease as compared to those who were hospitalized with COVID.

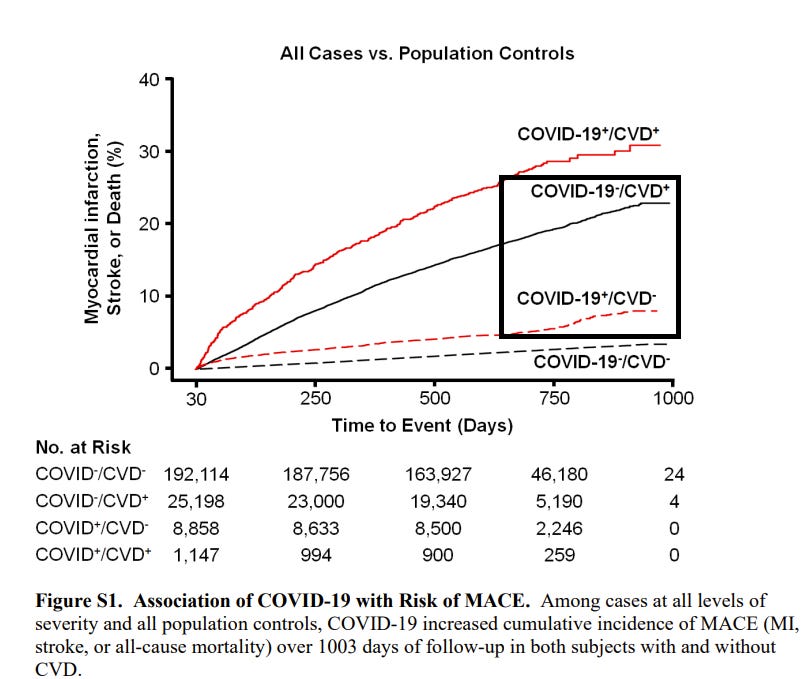

So maybe there’s a bit more to the story that isn’t being told, and that brings us to the Supplementary Material. Note here that the authors make a one-off comment that when comparing all COVID+ cases and incidences of MACE to those within the population control group there was a far greater risk of MACE among those who got COVID:

Consistent with prior studies, COVID-19 at all levels of severity was associated with significantly higher risk of MI, stroke, or all-cause mortality over 1003 days of follow-up (HR, 2.09 [95% CI, 1.94–2.25]; P<0.0005; FigureS1; Table S4).

Funny that this graph was left in the Supplementary section, because if one were to look at this section, you’d notice that this “converging” effect completely disappears:

In essence, when you include outpatient people with COVID but no cardiovascular disease the MACE incidence drastically declines. Or put another way, that would suggest that incidences of MACE were likely very low among those who did not require hospitalization for COVID.

Interesting that researchers can collect all this data together and come up with an “all severity category”, and yet when you look a little deeper you can figure out that there’s a clear difference between those did not need hospitalization for COVID and those who did.

Because a large driver of this uptick in MACE incidences is derived from the hospitalized patients.

The authors don’t provide an analysis for outpatient COVID patients, and their incidences of MACE as compared to the population control. Wouldn’t this analysis help to confirm the notion that all levels of COVID severity would put one at risk? The data is already there, and thus the analysis shouldn’t be difficult to conduct, so why leave out this analysis?

We must consider this situation from the perspective that absence of evidence does not necessarily mean evidence of absence. And yet, the fact that such an analysis of COVID positive outpatients is missing would warrant questions regarding whether the hazard ratio from such an analysis would be nonsignificant or minimally significant.

At this point readers may find this analysis redundant. As in, it certainly would make sense that the those who are hospitalized would be at greater risk of developing MACE following COVID compared to those who didn’t require hospitalization.

But this begs the important question- is there something about hospitalized patients that may explain why they may be hospitalized for COVID to begin with.

The evidence is there as well when we compare demographic information between the hospitalized COVID patients to all COVID+ patients.

Apologies for the horrendous editing, but the point should be pretty clear. The left column shows the demographic breakdown for all COVID positive patients while the right column shows demographic information for only COVID hospitalized patients. The important portion of this table is the bottom portion which outlined medical breakdowns of the patients.

We can see here that 1/5 of all COVID patients were hospitalized. This would-at least for the sake of parity- tell us that we should expect that 1/5 of the COVID positive patients with diabetes, asthma, or on medications for cholesterol or hypertension would make up the COVID hospitalized patients. Instead, readers can see that the actual makeup of COVID hospitalized patients with these comorbidities is far higher. For instance, around 40% of all COVID positive patients with diabetes (n=1,233) were hospitalized (n=498).

Put another way, what this tells us is that those who were hospitalized for COVID were likely to be more unhealthy and more likely to be on medications for chronic conditions relative to patients who did not require hospitalization.

This is an important distinction because it tells us that the risk of developing MACE is not just made more pronounced because of COVID hospitalization, but is made more pronounced due to prior comorbidities that may make one more likely to be hospitalized for COVID.

And this isn’t a controversial statement: a multitude of studies have come out recognizing that poorer health because of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, and a myriad of other diseases are associated with increased risk of COVID hospitalization.2,3 In fact, the NIH has come out with several articles noting the risk of comorbidities on COVID hospitalization.

Bear in mind that we haven’t even addressed the fact that the mean age of the participants in this study was around the mid-upper 60s- hardly an appropriate measure of MACE risk for younger people.

Age itself already carries with it both a risk of increased MACE risk as well as a risk for COVID hospitalization, and so these two factors can’t be taken out of consideration for these results. Of course, it’s important to recognize that age is also related with various comorbidities, and thus these two factors are closely entangled.4,5

Rational risk and misleading headlines

If you look up any articles related to this current paper you’ll come across headlines such as the following:

Looking into any of these articles it’s quite clear they all hit the same talking points, and it makes me curious if any of these journalists bothered to read the study themselves to pick it apart.

The CNN headline is pretty misleading already given that hardly any patients were included up to the 3-year mark, likely due to there being so few patients who were infected during early 2020 to make it to the 3-year mark. The better cutoff would have been the two-year mark, but that doesn’t make for a good headline.

The articles above represent the many failures in science journalism. There’s no critical analysis of the study in question, and instead defaults to talking points that only serve to stoke fear into people who can’t be bothered to understand a study for itself. The fact that several of these arbiters of fact-checking couldn’t do their due diligence and look at these studies themselves just adds to the hypocrisy at play.

There’s more that can be said about this study, but for the most part this is a study that is hardly generalizable to the public. It’s a study that relies on a specific group of individuals who appear to be at greater risk of COVID hospitalization to begin with, and quite frankly at greater risk of developing MACE independent of COVID infection.

Even more importantly, it’s a study that tells us something important, and something that has mostly been discussed by COVID vaccine skeptics.

That is, given the wide disparity in MACE events between COVID hospitalized individuals and those who just test positive, and given that those who were hospitalized were more likely to be unhealthy, wouldn’t the best thing to do to prevent MACE to be to get people to be more healthy?

Shouldn’t the findings here tell us that an approach worth considering would be to do what is possible to keep people out of the hospital to begin with?

Instead, the narrative seems to be more allopathic medication- giving people more medicine prior to a COVID infection while also given them medicine to reduce their risk after getting ill. No discussion is being provided on helping to keep people healthy to begin with.

This just points to further failures in journalists, and further failures in science.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Hilser, J. R., Spencer, N. J., Afshari, K., Gilliland, F. D., Hu, H., Deb, A., Lusis, A. J., Wilson Tang, W. H., Hartiala, J. A., Hazen, S. L., & Allayee, H. (2024). COVID-19 Is a Coronary Artery Disease Risk Equivalent and Exhibits a Genetic Interaction With ABO Blood Type. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.321001. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.321001

Sanyaolu, A., Okorie, C., Marinkovic, A., Patidar, R., Younis, K., Desai, P., Hosein, Z., Padda, I., Mangat, J., & Altaf, M. (2020). Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN comprehensive clinical medicine, 2(8), 1069–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4

Gasmi, A., Peana, M., Pivina, L., Srinath, S., Gasmi Benahmed, A., Semenova, Y., Menzel, A., Dadar, M., & Bjørklund, G. (2021). Interrelations between COVID-19 and other disorders. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.), 224, 108651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108651

Farshbafnadi, M., Kamali Zonouzi, S., Sabahi, M., Dolatshahi, M., & Aarabi, M. H. (2021). Aging & COVID-19 susceptibility, disease severity, and clinical outcomes: The role of entangled risk factors. Experimental gerontology, 154, 111507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111507

Zimmermann, P., & Curtis, N. (2022). Why Does the Severity of COVID-19 Differ With Age?: Understanding the Mechanisms Underlying the Age Gradient in Outcome Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection. The Pediatric infectious disease journal, 41(2), e36–e45. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000003413