The Dangers of Chronic Stress

Why constant anger and stress is deleterious to the body.

Edit 11/6/2022: Links have been added to the amnesty post as well as the relevant part of one of my Catecholamine posts that discusses the self-fulfilling prophecy of fear and adverse reactions. Apologies for forgetting to include them prior to publication.

In writing Thursday’s post I opined on the fact that COVID discourse has left me melancholic and rather stressed. It’s one of the reasons why my perspective on forgiveness has changed from what I originally thought before: it doesn’t quite do one good to always be resentful and angry, even if the anger is rightful in nature.

Several people shared similar sentiments, and I’ve seen several people comment about how the COVID paranoia has left them in an angry state but that they would rather not act out of emotional anger or continue to stew in such feelings.

Being constantly stressed and inundated with negativity can weigh heavily. We know full well that being stressed is not good for our health, and yet we tend to live in a state of perpetual deep stress.

Paired with modernity and social media it’s quite clear that messages and narratives we see on a daily basis tend to lean towards negative more than positive or something with some degree of levity.

Overall, we tend to live stressed out, craving things that aren’t good for our stress and anger levels even though we know it’s not good for us.

So why exactly is prolonged stress bad?

Let’s venture into some of the literature and sleuth around. Hopefully the evidence there can provide some perspective on why being angry and stressed all of the time may actually make us more unwell overall.

Table of Contents

Acute vs Chronic Stress

Stress isn’t all bad, and in many ways stress is a necessary response that has been shaped over millions of years of evolution.

Stress itself can come from many places, either in the form of physiological stressors such as cuts, wounds, or infection or psychological through changes in emotion. Stress can also come from internal sources such as cognition or it can be externalized through social or environmental cues.

For our ancestors, acute stress was critical for survival. Hostile environments require quick engagement of the sympathetic nervous system (or the flight-or-fight response), and a sudden influx of immunological cells and markers can help fight off infections and heal wounds after a sudden injury. Acute stress was a necessary physiological and psychological response that allowed our species to persist.

However, if stressors continue to persist past short-term exposure you may enter into a phase of chronic stress, in which case the engagement of various biochemical pathways begin to become exhausted and may become deleterious to our overall health.

Chronic stress can come from many sources. Unlike our ancestors who may have been concerned about predators, moderns tend to suffer from the stresses of work, social media, and friend/family dynamics. There’s also many chronic illnesses such as cancer and HIV that can produce their own stressors.

It’s hard to find a specific definition on chronic stress, but most tend to focus on the idea of psychological stress.

Yale Medicine defines chronic stress as:

A consistent sense of feeling pressured and overwhelmed over a long period of time

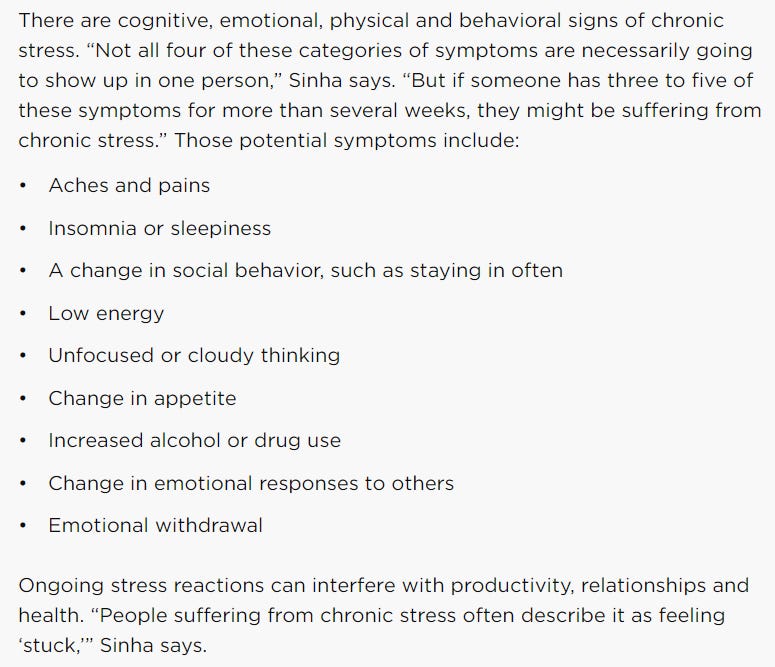

And includes the following symptoms of chronic stress below:

A lot of these symptoms come from the perspective of psychological insults or stressors. It’s important to remember that many of the physical/emotional symptoms of chronic stress may not match what was listed above.

However, if one does notice several of these symptoms it wouldn’t be too far-fetched to consider a diagnosis of chronic stress.

For people who are dealing with chronic or life-threatening illnesses chronic stress may be a side effect of dealing with such issues. It’s noted that chronic stress can occur in those dealing with cancer and other diseases, and can actually occur in family members who are helping those dealing with chronic illness as well.

Now, more important than the symptoms may be where these symptoms come from. It should come as no surprise that continuous engagement of various biochemical processes may end up becoming harmful in the long run.

The Ramifications of Chronic Stress

The symptoms of chronic stress can be both vague and varied. So too are the biochemical processes that are responsible.

It’s important to remember that many of our body’s physiological responses are intrinsically tied to multiple biochemical pathways, signaling events, and the production, release, and removal of various chemical agents.

This also means that many of our bodily functions are more intrinsically tied than would appear.

A few months ago I noted that several cytokines are released in response to an infection, and that the release of these cytokines are related to feelings of fatigue and sleepiness. Two well-known cytokines to show this effect are Interleukin-1 and tumor-necrosis factor, and they may explain why we tend to feel sleepy when trying to fight illnesses.

This reminds us that things within our body are more closely related than would appear on the surface.

Chronic Stress and Immunity

Chronic stress and anger has been strongly implicated in immune dysregulation and alterations in recovery. Chronic stress may also target endothelial function and may alter mucosal immunity functions, which may be related to colitis and elevated risk of GI cancer (we’ll cover this a bit more further on).

For instance, Brod, et al.1 notes the following:

However, further clinical and experimental studies have shown that in other instances, often when sensations of stress or anger become persistent, our immune response may become notably diminished or imbalanced. Individuals with below average levels of anger control were shown to heal significantly slower than subjects less disposed to this emotion.13 Similar observations were made in a study comparing differences in wound healing among students during their summer vacation and the run up to their exams. Recovery during the stressful exam period was on average 3 days slower than during vacation with a reported 68% reduction in IL-β production.14 In a number of studies Kiecolt-Glaser and colleagues have demonstrated that chronically stressful situations such as those experienced by caregivers can weaken the immune response, significantly diminishing antibody production against influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia vaccines and increasing the chance of latent herpes simplex virus flare ups.15–17 Further, in a range of clinical and experimental studies Dhabhar and his collaborators have also shown that chronic and acute stress can trigger both a deleterious and a protective T-cell response in a wide variety of immune-related disorders including cancer, allergy and post-operative recovery.18–25

Several of these studies infer correlative findings, and so these findings should be taken with caveats.

Indeed, research tying stress and anger to altered physiological responses has been rather limited, so keep this in mind as we make do with what we can find.

An assessment of school examination2, which of course tends to be highly stressful, suggest that collection of saliva IgA from students during the early periods of an exam show elevated levels of S-IgA while collection during the later time periods show a decrease in S-IgA. The data here is limited, and how it relates to chronic stress is difficult to discern, but it’s interesting to wonder if chronic stress may actually limit the ability to secret antibodies.

Evidence also suggests that chronic stress may blunt the effects of natural killer cells. During acute stress the body releases natural killer cells to aid in surveillance and elimination of pathogens, generally caused by the release of catecholamines that activate the sympathetic nervous system.

For those who experience chronic stress, NK cell activity may appear to be attenuated, possibly due to tolerance to cytokine responses (Dragoş, D., & Tănăsescu, M. D. emphasis mine; context added3):

Conversely, chronic stress reduces the NK cell responsiveness to cytokines [56], with a drop in the NK cell activity, in contrast to the increased activity in normal individuals subjected to an acute stress. NE [norepinephrine/noradrenaline] may be one of the factors mediating this effect, which was shown to reduce NK cytotoxic capacity in vitro [57]. Exposure to chronic stress results in a decreased NK cell ability to kill target cells [13], and diminished response to recombine interferon gamma [58], which may partially explain the chronic stress associated morbidity, as impaired NK function correlates with the development or progression of viral, autoimmune, and neoplastic diseases. However, the immune cell functional capacity recovers relatively quickly: it begins within 1 month and is substantial within 1 to 3 months after the conclusion of the overtaxing situation [59]. Of course, this holds as long as no other major stress supervenes in the next few months.

If exposed to an acute psychological challenge, chronically stressed individuals have a protracted decline in NK cell activity [41] and a more pronounced redistribution of NK cells. Normally, acute stress is associated with a hormonal upsurge in the SAM [sympathetic-adrenal-medullary], HPA [hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal] and endorphin systems. In individuals previously exposed to chronic stress, these acute stress–induced changes are altered, with an excessive adrenergic response and a blunted beta–endorphinic one [41].

Chronic stress may also affect humoral and cellular immunity, possibly through alterations in response to signaling molecules as well:

In contrast, chronically stressed individuals have a drop in the percentage of circulating CD62L(minus) T lymphocytes [61], which is associated with a decrease in the sensitivity and density of the beta2–adrenergic receptors on lymphocytes [62] and therefore, a drop in the sympatho–adrenergic driven stimulation of immune cells. This may have consequences on the immune cells' readiness to mobilize and migrate in response to acute stressors and implicitly on the organism's ability to defend itself.

Chronic stress decreases the lymphocyte proliferative ability in response to mitogens [63], to lectins, and to T–cell receptor activation [58]. It may also diminish the percentages of total T lymphocytes and of Th lymphocytes, and it may increase antibody titers to Epstein–Barr virus (as a consequence of the cellular immune system's inability to control the latent virus) [64].

For all intents and purposes, it would appear that general chronic stress may induce some level of tolerance in immune cells to signaling (almost like “the boy who cried wolf” paradox). It makes sense, as chronic signaling with no inherent benefit to the body would be wasteful. However, this paradoxical tolerance may also inhibit the ability for the immune system to respond to actual pathogens, and may make those dealing with stress more susceptible to infections.

But this also doesn’t affect infections, but also the regulation of tumor growth and cancer.

Chronic Stress and Cancer

As the effects of the immune system also carry over to cancer development, we may infer that there may be a relationship between chronic stress and susceptibility to cancer or tumor growth.

Indeed, the impaired innate and adaptive immune response in chronically stressed individuals may promote tumor growth and metastasis.

As noted above, chronic stress can affect endothelial function, and it appears that stress can lead to a common symptom called colitis (inflammation of the colon) and increased gut permeability which can influence colon cancer and gastroinstestinal issues (Zhang, et al.4):

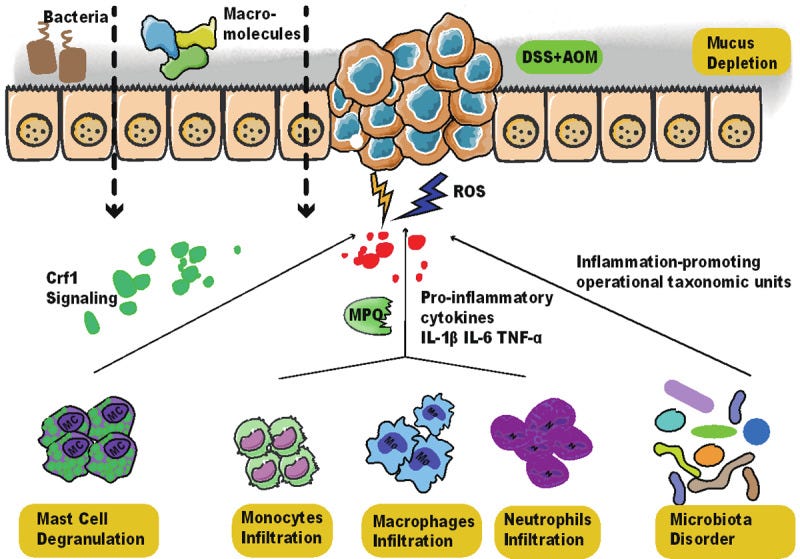

Chronic stress has been reported to induce barrier dysfunction in ileum and colon and initiate mucosal Inflammation, during which macromolecular permeability increases and mucus is depleted [15]. The mucosa of the stressed rats is seen with activated mast cells, increased infiltrate of neutrophils, ly6Chi macrophages, and mononuclear cells, the reinforced activity of myeloperoxidase (MPO), and more inflammation-promoting operational taxonomic units [16]. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtype 1 (CRF1) signaling is a positive regulator of psychological stress-induced mast cell degranulation [17] and tumorigenesis [18]. The much less tumorigenesis in Crf1 (-/-) mice is accompanied by a lower inflammatory response, including decreased interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) expression and macrophage infiltration and increased interleukin-10 (IL-10) expression [18]. Therefore, it is plausible that chronic stress can enhance CRF1 signaling in mast cells and promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis (Figure 1).

Stress-induced colitis and colitis flare-ups caused by stress, as well as other diseases of the gut, have been well-documented in the literature.5

Due to the immunological response from this inflammation it’s assumed that the gut microbiome may be altered, and the inflammation and release of reactive oxygen species itself can make for a dangerous microenvironment conducive to tumor growth.

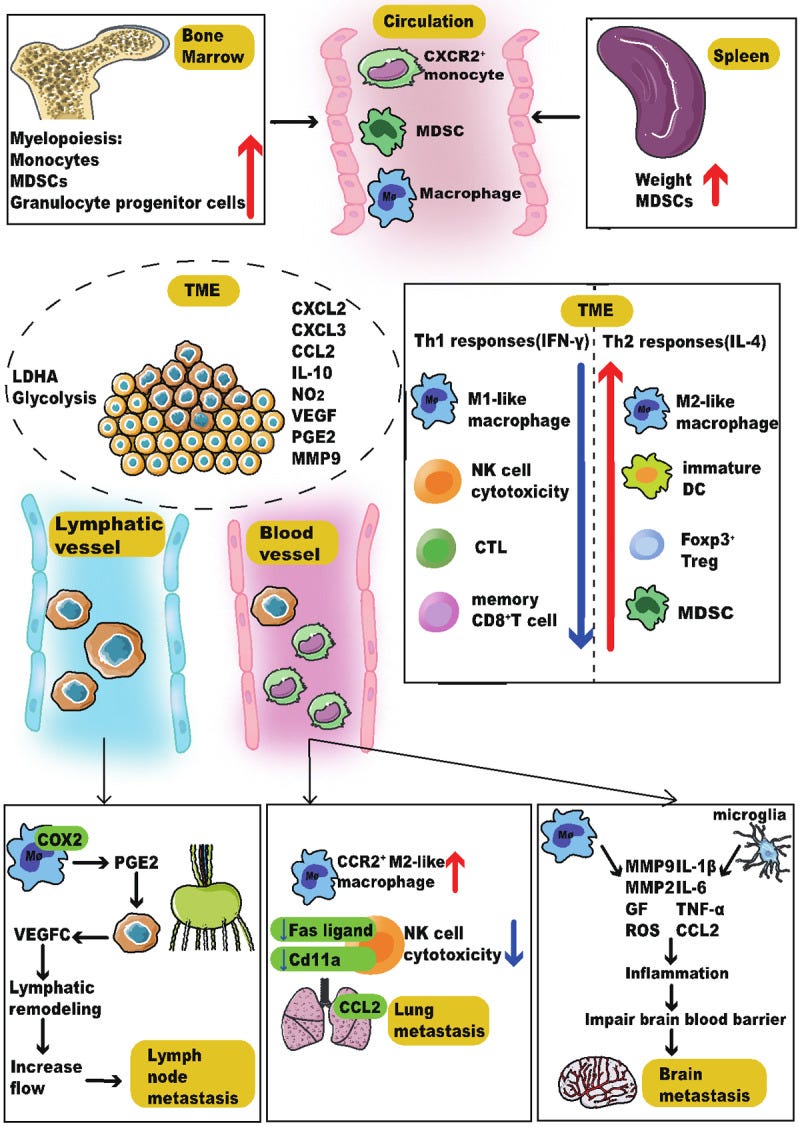

The overall effects of chronic stress may also influence tumor metastasis (infiltration of tumor cells into neighboring organs and tissues) in various organ tissues, again through disturbance in natural killer cell activity as well as the pro-inflammatory environment.

A schematic summary is provided below. Although it’s rather dense with abbreviations, visualize it for the cascade of events that may influence metastasis in several organs.6

Chronic Stress and Cardiovascular Disease

Last, but certainly not least, stress has a clear effect on blood pressure and atherosclerosis (plaque build-up; AS). It’s probably one of the more common aspects of chronic stress that we’ve all heard about. Still, such effects are extremely concerning, especially given that cardiovascular disease is the main killer of both men and women.

Yao, et al.7 notes some of the effects of stress on the heart below (emphasis mine):

Chronic stress is pervasive during negative life events and can lead to the formation of plaque in the arteries (AS). The relationship between stress and chronic disease is even stronger than that between stress and infectious or traumatic illness,3,4 among both adults and adolescents.5,6 Although physical activity is an important contributor to health, it does not significantly reduce the strong relationship between stress and accidental cardiovascular disease.7 The effect of chronic stress on AS involves multiple complex mechanisms that remain to be fully elucidated.8 Autonomic disorders caused by chronic stress may be a common mechanism that increases AS risk.9 The resulting imbalances typically include one or more of the following aspects: inflammation, signal pathways, lipid metabolism, endothelial function and others. The secondary aspects include pathogen burden, heightened immunity, high-fat diet, depression, macrophage-specific reverse cholesterol transport (m-RCT), blood pressure, chromatin landscape and hematopoietic cells. Specifically, research shows that inflammation that may occur simultaneously with chronic stress is strongly related to endothelial dysfunction, an antecedent to AS and thrombotic disease.10–12 Pain, heat, redness, swelling and loss of function are typical signs of inflammation, which is related to chronic stress.13,14 Chronic stress may directly inhibit the diastolic function of a vessel via endothelial cells, and patients with long-term chronic psychological stress may develop diminished vascular endothelial function.15

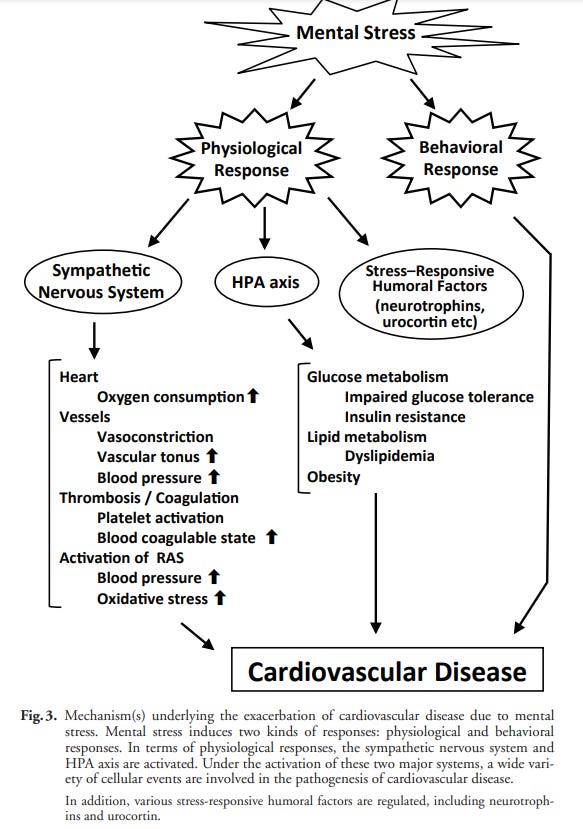

The effects on the heart are ones we’ve seen already based on the physiological effects listed above.

Chronic engagement of the sympathetic nervous system and the release of catecholamines may downregulate the HPA pathway while upregulating the SAM pathway leading to persistent inflammation.

The constant stimulation of SAM may also lead to elevated blood pressure and vasoconstriction—symptoms typical of engaging the sympathetic nervous system— which can lead to plaque buildup and elevated risk of cardiovascular disease.

The effects can be summarized below from Inoue, N.8

Note that there’s a balance at play here, in which constant exposure of select immune cells to catecholamines may have a tolerance-like effect, whereas the effect on other cells may actually lead to chronic upregulation, such as alterations in endothelial cells.

Be Mindful of Your Stress and Anger

When writing my catecholamine series I made mention of a paradoxical scenario.

Given that there’s evidence to suggest that the sudden cardiac deaths post-vaccination, as well as the incidences of myocarditis appear to have an association with catecholamine release, and that catecholamine release occurs under times of stress, one must wonder what effects messaging has on the adverse events we are witnessing given that much of the messaging is fear and anxiety-inducing.

Some of the literature on chronic stress suggest that vaccination while suffering chronic stress may not actually provide the same level of immunity as those who aren’t suffering chronic stress.

But that also may occur with adverse reactions post-vaccination as well.

In essence, what effect does fear of myocarditis cause in the presentation of myocarditis in those who get vaccinated? Is there almost a self-fulfilling prophecy at play here, where constantly negative messaging that creates fear and anxiety may actually increase one’s risk of suffering an adverse reaction?

The same can be said for those who get COVID— could messaging that overstates the dangers of COVID actually make one more susceptible to severe disease?

Some evidence of COVID hospitalizations from the UK indicated that up to 40% of the patients had high levels of fear and anxiety. It’s hard to pinpoint if such symptoms are due to chemical alterations caused by the infection, or if such symptoms were caused by true fear and anxiety that made one more susceptible to becoming hospitalized.

When looking at chronic stress we may turn a blind eye to the actual signs. We may tell ourselves that we hold onto anger because anger let’s us remember (I’ve actually stated this before).

But if that makes us worse off then what good does that do for our own well-being?

Keep in mind that much of the literature on chronic stress and health outcomes are both preliminary and correlative.

There’s plenty of people who have chronic stress who manage it well. There’s also many people who may not realize that their feelings of being unwell may actually stem from chronic stress.

However, that doesn’t mean that stewing in constant anger is good for one’s health. In fact, it could very well prove deadly.

It’s something to keep in mind during these times. As we try to think about who to forgive and forget, remember to think about yourself and your health as well.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Brod, S., Rattazzi, L., Piras, G., & D'Acquisto, F. (2014). 'As above, so below' examining the interplay between emotion and the immune system. Immunology, 143(3), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12341

Bosch, Jos A. PhD; De geus, Eco E. J. PhD; Ring, Christoffer PhD; Nieuw Amerongen, Arie V. PhD. ACADEMIC EXAMINATIONS AND IMMUNITY: ACADEMIC STRESS OR EXAMINATION STRESS?. Psychosomatic Medicine: July 2004 - Volume 66 - Issue 4 - p 625-626

Dragoş, D., & Tănăsescu, M. D. (2010). The effect of stress on the defense systems. Journal of medicine and life, 3(1), 10–18.

Zhang, L., Pan, J., Chen, W., Jiang, J., & Huang, J. (2020). Chronic stress-induced immune dysregulation in cancer: implications for initiation, progression, metastasis, and treatment. American journal of cancer research, 10(5), 1294–1307.

Levenstein, S., Prantera, C., Varvo, V., Scribano, M. L., Andreoli, A., Luzi, C., Arcà, M., Berto, E., Milite, G., & Marcheggiano, A. (2000). Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. The American journal of gastroenterology, 95(5), 1213–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02012.x

Some definitions are included below:

Myelopoiesis: production and development of cells from bone marrow.

MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells- cells that are prominent during cancer and aid in immune suppression and cancer development.

TME: tumor microenvironment

Yao, B. C., Meng, L. B., Hao, M. L., Zhang, Y. M., Gong, T., & Guo, Z. G. (2019). Chronic stress: a critical risk factor for atherosclerosis. The Journal of international medical research, 47(4), 1429–1440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519826820

Inoue N. (2014). Stress and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis, 21(5), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.21709

Truly magnificent piece of reporting. Congratulations. An interesting study by Salvatore Maddi, University California in 1980’s followed 430 employees of Illinois Bell, when the company was going through breakup. Many employees suffered chronic stress, divorce, substance abuse etc, but they found a cohort of one-third fared very well. When they investigated their backgrounds they found the same as most other employees who did not do well, except that they were encouraged to believe they were special and their privations were a preparation for their future leadership. In other words they were taught by their parents to transcend chronic stress as a preparation for leadership. Hormesis allows us to sublimate chronic stress into utility.

This, of course isn’t new. Thank you for putting it together it was nicely done. But I think venting is a valuable tool to help release that anger. Talk therapy for example. I see what has happened on the last week as group talk therapy. Oster was the trigger. I personally feel better for expressing my feelings. I also feel less ashamed for my anger. I am happy to know I am not alone with these feelings. Personally my sense of well being has increased.