What's going on with the Ozempic craze?

A look at the Type II diabetes medication turned weight-loss "miracle".

By now, many readers have likely come across the new pharmaceutical craze used by Hollywood elites called Ozempic. It seems as if the limelight for COVID vaccines have gone away for another quick miracle drug.

You’ve likely come across an Ozempic commercial which, unironically, is based off of Pilot’s song It’s Magic, as if to insinuate that the drug is a magical drug. I will, however, contend that the commercial is rather catchy…

When these commercials first aired I found it a bit strange that there were these comments that Ozempic may lead to weight loss (the above commercial also prefaces this remark with the note “Ozempic is not a weight-loss drug”). How exactly would a drug for diabetes also help induce weight loss?

So it’s interesting that such drugs have taken off recently, with many Hollywood/social elites such as Elon Musk and Chelsea Handler coming out about their use of the drug for weight-loss1, with the list continuously growing.

Recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics has included medications such as Ozempic and other similar drugs into their recommendations for childhood obesity, making it the first time that pharmaceuticals have been included in such guidelines2.

With this new Hollywood craze and widespread media coverage, these diabetic turned weight-loss medications began seeing a shortage at the end of 2022 and into early 2023, leaving those who require the drug for managing their diabetes to struggle with finding supplies. Novo Nordisk, the maker of Ozempic, has remarked a few weeks prior that sufficient supplies of the drug should be available now. On one hand, this suggests that the shortage may no longer be a concern, while simultaneous raising other worries that the drug may be prescribed even further for weight loss.

In a world that has argued against the use of off-label drugs, it’s rather ironic to see that these drugs intended for Type II diabetes are being used off-label for weight-loss—something that many COVID zealots should criticize if we expect some level of consistency.

But what exactly is Ozempic, and how does this expensive drug work both in treating diabetes as well as a weight-loss drug?

Pharmacology of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 and Incretin Hormones

Many pharmaceuticals in use are not purely synthetic, but may be derived from endogenous molecules which are slightly modified in order to produce stronger, longer effects within the body.

Semaglutide, which is sold under the brand names Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus (among others), acts as a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs).

As its name implies, Semaglutide is modeled after GLP-1, which is a peptide hormone naturally produced by the body.

GLP-1 was discovered through research into the hormone glucagon. Glucagon, which is produced in the pancreas like insulin, acts as an antagonist to insulin and serves as one piece in the extracellular glucose feedback mechanism— where insulin decreases circulating glucose glucagon increases it (i.e. produces a hyperglycemic effect).

Research into glucagon and other hormones related to blood sugar led to the discovery of other similar structures. For instance, researcher Roger Unger characterizing an anti-glucagon antibody, which allowed for detection of glucagon in blood and tissue samples via labeling, which allowed for further detection and research. However, it was found that utilization of this antibody also lead to reactivity towards other proteins, leading to the discovery of “glucagon-like” molecules. Unlike glucagon, which is produced in the pancreas, these glucagon-like molecules were detected in the intestines.

Interestingly, injection of these glucagon-like molecules in dogs didn’t appear to produce the hyperglycemic effects that glucagon does. Instead, the use of these molecules activated insulin excretion, suggesting a hypoglycemic effect with this peptide and a possible pathway of controlling blood sugar.

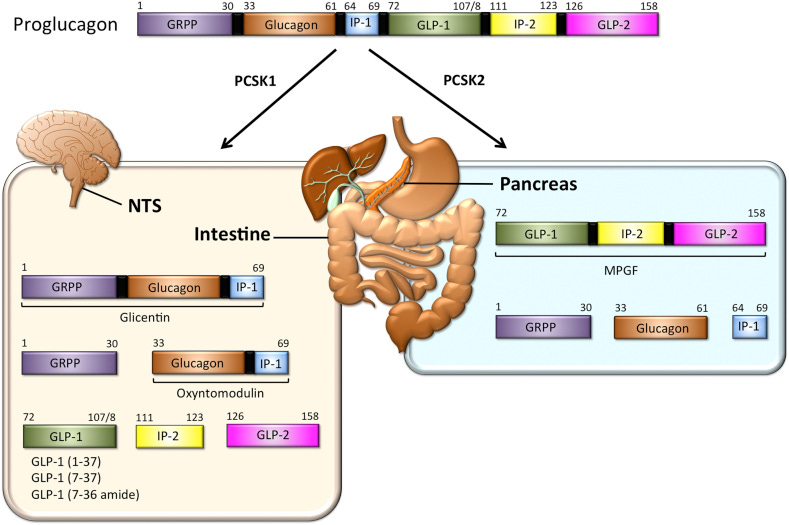

Further research would eventually recognize that both glucagon and these glucagon-like peptides, of which GLP-1 is one, are derived from a larger protein called proglucagon, with this larger precursor becoming modified based on the organ in which it is being produced (glucagon in the pancreas and GLP-1 in the intestines):

For instance, within the pancreas glucagon has been identified as well as a large proglucagon fragment later named…major proglucagon fragment (MPGF).

Due to the scope of this article further discussion of GLP-1 is limited. More can be found about GLP-1 in this rather exhaustive review from Müller, et al.3:

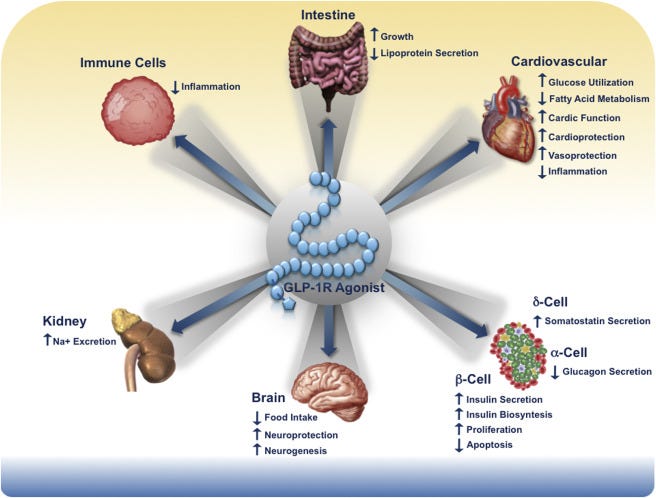

GLP-1 also falls under a group of compounds called incretin hormones (incretins for short), which are hormones released when food is consumed that help regulate insulin, and actually play critical roles in other parts of the body.4

When someone consumes nutrients GLP-1 levels drastically increase and bind to GLP-1 receptors on the surface of pancreatic beta cells, leading to release of insulin (termed insulinotropism) and downregulation of glucagon.

In those with Type II diabetes it's been suggested that this pathway is possibly disturbed or obstructed, possibly through glucose tolerance. The use of GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic for Type II diabetics are suggested to help revive the insulin excretion from the pancreas and maintain glucose homeostasis via the hypoglycemic effect.56

Although this effect of increasing insulin excretion may help aid diabetics, what’s curious about Semaglutide is its strange association with weight loss, with many people reporting a lack of appetite when on GLP-1RAs.

Given that incretin hormones are released when consuming food, it’s possible that a signaling pathway involving incretin hormones may also be utilized to signal fullness.

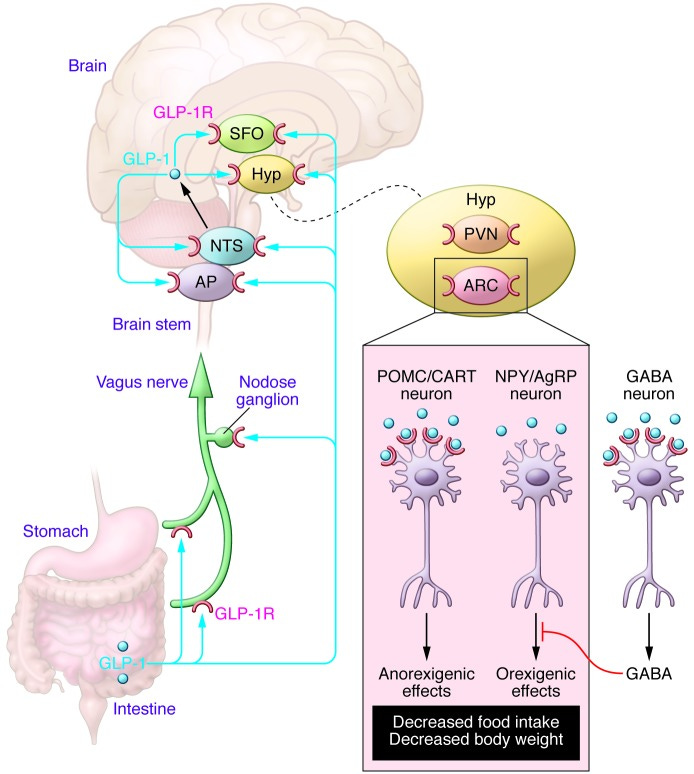

Indeed, it appears that the brain and CNS also contain GLP-1 receptors, which also respond to the GLP-1 released after eating. It also appears that some aspects of the nervous system may also produce GLP-1 themselves (Baggio, L. L., & Drucker, D. J.7):

The relative contributions of signals from regions within the peripheral nervous system or CNS that transduce the anorectic effects of GLP-1R agonists are not known precisely; however, candidates include the vagus nerve, nodose ganglia, hypothalamic nuclei, and the brain stem. Brain-derived GLP-1 is synthesized in a subset of neurons in the NTS that project to GLP-1R–expressing regions in the hindbrain and hypothalamus, including the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), dorsal medial nucleus of the hypothalamus, and arcuate nucleus (ARC), as well as the NTS itself. A small amount of GLP-1 may also be synthesized within the hypothalamus itself (11), and gut-derived GLP-1 may communicate with the brain by accessing GLP-1Rs within fibers innervating the portal vein or the nodose ganglion of the abdominal vagus nerve.

In this case, the feedback mechanism from GLP-1 produces an anorectic (appetite-reducing) response which can decrease food intake. Thus, there’s an artificially induced effect of fullness produced by these GLP-1RAs.

It should be noted that the weight-loss effect of GLP-1RAs are inconsistent, and are likely due to the binding affinity and pharmacokinetics of each drug. Several of these studies were also conducted in mouse models which may not reflect human physiology.

Regardless, what would otherwise seem like a paradoxical response to stimuli are actually based on different responses, localized to regions of the body which utilize this GLP-1 receptor.

And in reality, this idea does not seem too far-fetched. Consider that this mechanism is contingent upon energy resources, in which food must be organized. It would be unwise to upregulate glucagon expression at a time when circulating glucose levels are likely to be elevated. Instead, excretion of insulin can help shuttle newly ingested carbohydrates to necessary regions of the body. At the same time, constant intake of nutrients may itself be detrimental. Thus, it’s possible that at higher levels circulating GLP-1 can activate corresponding neurons to release a signal to halt eating.

Semaglutide Structure

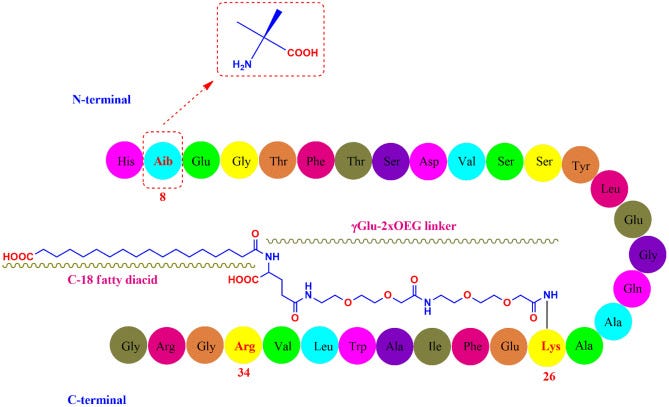

In order to increase the binding affinity and reduce metabolism of GLP-1 various modifications were made, eventually resulting in the structure of Semaglutide.

Mahapatra, et al.8 details some of the modifications made to GLP-1:

Semaglutide (C187H291N45O59; 4113.58 g/mol) has 31 amino-acid containing peptidic structure (Fig. 1) which is 94% homologous to the native GLP-1 for avoiding immunogenicity [23]. The alanine residue at 8th position is substituted with Aib (2-aminoisobutyric acid) which protects semaglutide from enzymatic degradation by DPP-4 [24]. Similar to liraglutide, the lysine residue at 34th position in native GLP-1 was replaced by arginine in semaglutide too. The arginine substitution at 34th position was helpful in production of GLP-1 analogue through semi-recombinant process [25]. Lysine residue at 26th position was acylated for attachment with a C18 fatty diacid through a hydrophilic linker “γGlu-2xOEG”, which prolonged the systemic half-life through enhanced albumin binding and reduced renal clearance [26].

Which are illustrated in the following figure:

In addition to the active compound Semaglutide, an enhancer called sodium N-[8-(2-hydroxybenzoyl) aminocaprylate], or SNAC, is added that helps reduce degradation and aid in absorption.

Like many other GLP-1RAs Semaglutide is predominately administered subcutaneously. However, oral forms (Rybelsus) are also available.

Other GLP-1RAs

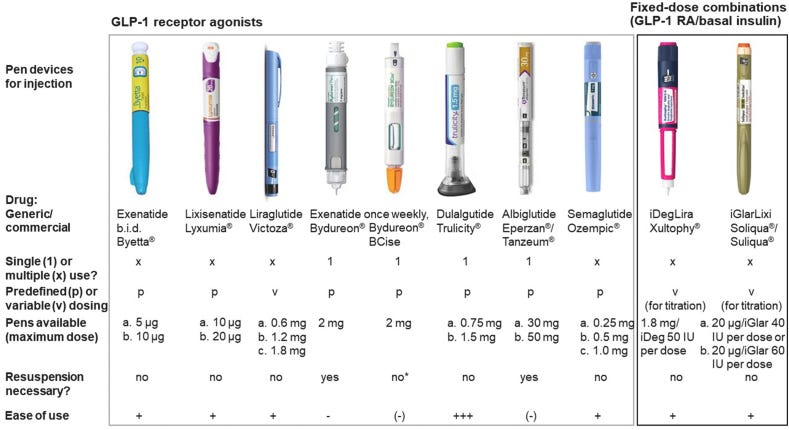

Although Semaglutide is the most widely recognized GLP-1RA on the market, other companies have developed their own receptor agonists in the past few years, with some of their descriptions provided below (Nauck, et al.9):

With a few characteristics of these GLP-1RAs described in a Table from Trujillo, et al.10:

Exendin-4 is peptide isolated from the venom of Gila monsters, which was shown to have GLP-1RA activity as well, leading to modifications and development of this peptide as another diabetic medication11.

Ozempic Rebound: the consequences of quick-fix weight-loss

Note: More can be discussed on this topic, with additional details in the citations provided above.

Along with stories of “Ozempic face”, which is really a consequence of rapid weight-loss (and possibly buccal fat removal which has also gained in popularity), there has also be a phenomenon of “Ozempic rebound” which has made its way in the media, spurred on by a review of a so-named STEP 1 trial extension12 which looked at weight gain after discontinued use of Semaglutide.

I have not read the article yet, but some points stick out such as the following remarks:

Weight regain has previously been observed following withdrawal of obesity pharmacotherapies, including orlistat and lorcaserin—and also semaglutide, as shown in STEP 4—despite continued lifestyle intervention.13-15 Taken together, these findings and those of the present study confirm the chronicity of obesity and highlight the importance of maintaining long-term pharmacological treatment for weight management in people with obesity.

A rather concerning remark to suggest that one solution to obesity is to continuously provide a pharmaceutical.

Considering that GLP-1RAs appear to have actual neurological effects (i.e. blocking hunger and mimicking satiation), there’s a serious mental component that’s worth considering with respect to these medications and their influences on the relationship people have with food.

That is, the loss of a “off” button in eating means that weight gain is possibly an inevitable result if one did not get behavioral and lifestyle factors under full control (i.e. they return to the old habits that contributed to their weight gain).

This is a consequence of sacrificing long-term lifestyle changes that will lead to better health for quick fixes where the main goal is just to lose weight. It’s also a growing sign of how out-of-touch many people are with what they put in their bodies- both food-wise and pharmaceutical-wise.

There’s no doubt that losing weight with our modern lifestyles would be difficult. However, the answer to these forms of adversity is not to reach for pharmaceutical means of weight-loss.

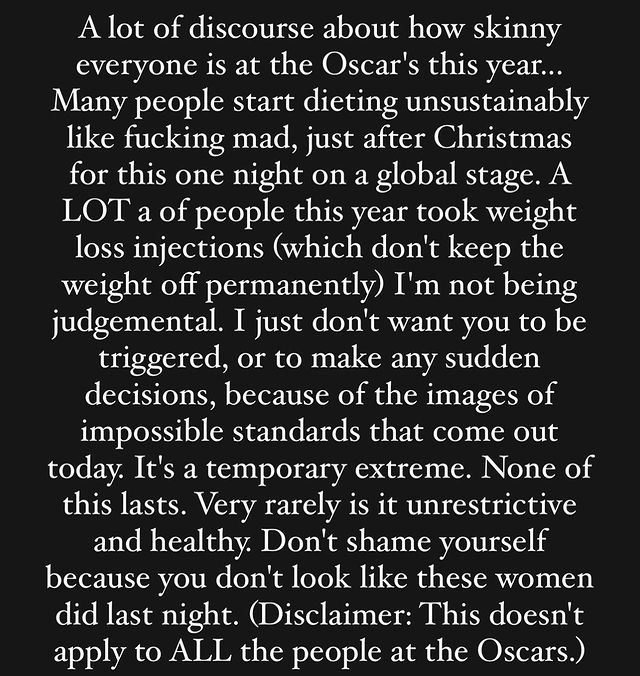

In contrast to some of the actors who have used Ozempic and the like for weight loss, actress Jameela Jamil came out criticizing the use of these drugs in an Instagram post from a few months ago:

Although I disagree with her assertions over “fatphobia” (obesity is linked to a multitude of comorbidities), the general sentiment here is correct. The use of Ozempic by the elites is bound to have an influence on the public, and in fact it’s possible that such a craze may help to change public perception in a manner that accepts widespread use of these drugs for weight-loss rather than the initial intended purpose.

It used to be a commonly held belief that Big Pharma does not have people’s best interests in mind, and yet more and more it appears that these ideas have been lost on many if it means a quick-fix is accessible. Again, I should reiterate that the use of Ozempic and other GLP-1RAs for weight loss is off-label, and again points to the hypocrisy at play in which certain drugs are allowed to be used for unintended purposes if accepted by those with higher social standing.

After the Oscar’s Jameela Jamil made another Instagram post once again calling out the use of these drugs:

In short, remember that there’s an incentive at work to instill a need for pharmaceutical approaches to health. Although these may benefit some, be wary of considering these as the first approach in weight loss. Don’t be influenced by catchy songs or Hollywood elites.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Chelsea Handler has remarked that she was unaware she was on the drug, which quite frankly seems like a rather suspicious remark (essentially taking something without realizing what it was).

In contrast to remarks made within the press and other places online, surgery has been included as an option for childhood/adolescent obesity for several years now.

For instance, a 2019 article from The AAP had noted childhood bariatric surgery as a possible factor in helping with obesity:

It’s likely that the noise around these new guidelines have brought to light this recommendation, which certainly raises concerns, but isn’t novel in the same ways that these drugs are now being included in the most recent guidelines.

Müller, T. D., Finan, B., Bloom, S. R., D'Alessio, D., Drucker, D. J., Flatt, P. R., Fritsche, A., Gribble, F., Grill, H. J., Habener, J. F., Holst, J. J., Langhans, W., Meier, J. J., Nauck, M. A., Perez-Tilve, D., Pocai, A., Reimann, F., Sandoval, D. A., Schwartz, T. W., Seeley, R. J., … Tschöp, M. H. (2019). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Molecular metabolism, 30, 72–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.010

Campbell, J. E., & Drucker, D. J. (2013). Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell metabolism, 17(6), 819–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.008

Collins L, Costello RA. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. [Updated 2023 Jan 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551568/

This is also why insulin is considered a contraindicator, as the combination of both a GLP-1RA and insulin may severely decrease glucose levels, as remarked in the ad.

Baggio, L. L., & Drucker, D. J. (2014). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in the brain: controlling food intake and body weight. The Journal of clinical investigation, 124(10), 4223–4226. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI78371

Mahapatra, M. K., Karuppasamy, M., & Sahoo, B. M. (2022). Semaglutide, a glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist with cardiovascular benefits for management of type 2 diabetes. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders, 23(3), 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09699-1

Nauck, M. A., Quast, D. R., Wefers, J., & Meier, J. J. (2021). GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Molecular metabolism, 46, 101102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102

Trujillo, J. M., Nuffer, W., & Smith, B. A. (2021). GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Therapeutic advances in endocrinology and metabolism, 12, 2042018821997320. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018821997320

Yap, M. K. K., & Misuan, N. (2019). Exendin-4 from Heloderma suspectum venom: From discovery to its latest application as type II diabetes combatant. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology, 124(5), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13169

Wilding, JPH, Batterham, RL, Davies, M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022; 24( 8): 1553- 1564. doi:10.1111/dom.14725

"There’s no doubt that losing weight with our modern lifestyles would be difficult. However, the answer to these forms of adversity is not to reach for pharmaceutical means of weight-loss."

You don't say! If we take a look around at the plant and animal kingdoms, it is possible to observe that certain life-forms do well in certain environments and with certain diets. Is there any life-form on earth that does well in an environment loaded with toxins and a diet of industrial processed and ultra-processed (I like simply 'adulterated') "foods"?

As I think you implied, there is only so much of this mess ('modern lifestyles') that we can fix. Still, most people could do better by just eating food instead of industrial glop. But it wouldn't be as cheap or convenient. (Related to "quick fix".)

I have struggled with weight gain most of my life. I have had to discover a number of different factors that were contributing to the problem, consumption of industrial glop (A.K.A. "food-like substances") being the most important one. About two years ago I found a combination of dietary and other adjustments that brought my weight down and kept it down without creating any major new problems. Finally! And keeping my older clothes really paid off.

Except that now I am underweight, for the first time in my life. Where does it end?

So I don't know any simple solution either. Popping pills sure isn't it. In fact I discovered something that surprised even the doctor that I work with (on a cash basis -- no interference from insurance companies). Five years ago I let myself be fooled into thinking that a certain genetic condition I inherited, that causes high LDL-C and super-high LP(a), was risky enough that I should try taking pharmaceuticals to lower cholesterol.

I won't go into details here about what I took, but around the same time, out of common sense, I adjusted my diet back to a reduced carbohydrate one that had worked previously but had created major new problems. By this time I knew the cause of those new problems (involving a birth defect) and I was able to compensate and avoid them. I also knew how much evidence there was for lowered cholesterol preventing heart attacks (I do also have heart disease), and losing excess weight made so much more sense to me. The cardiologist was uninterested in that. (He eventually removed himself from my life by wasting an appointment where he tried rather hard to persuade me to "get the shots". That's the last I ever had anything to do with him. Contraindications, what are those anyway? Fortunately, I knew them well.)

The result of this diet, that worked so well before? Nothing. Weight steady, and significantly overweight. It took three more years and a miracle to learn what was wrong. It was the cholesterol-lowering drugs. Working with my doctor, I had learned that the hereditary problem I have was not the death sentence that the industry would like us to believe, and that its risk did not correlate with cholesterol levels. So I dumped the drugs. The miracle was learning that they could prevent weight loss. And the diet started working. Over the next year, I lost the excess weight and moved into my ideal range. But then another 5 pounds below that, before it leveled off. And then another 5 pounds suddenly lower a few weeks when something got me that I couldn't identify (it has passed).

I have regained that last 5 pounds, and will be back in my ideal range soon. (I can identify 'ideal' by how I feel.) My doctor is providing information about what else I need to do about aging and muscle loss (the likely cause of my underweight). He's seen this work before. There is no pill for it. It involves exercise. I have problems with exercise because of an endocrine disorder (quite possibly iatrogenic), but there are still ways to make it work. No, it's not as convenient as popping a pill, but it actually works and isn't poisonous. That should be worth something.

As I have now said numerous times in numerous places on Substack and elsewhere, I have a view of life -- all life -- as having been designed and created. Each life-form has its particular design requirements. Violate those and you've got trouble. Pay attention to creation and creator and you are apt to do well, even if physical life is less than perfect. That is my view, and others can believe as they wish. It may not make sense to some, but popping pills to lose weight makes absolutely no sense to me.

Just a few points, these drugs are injected daily or weekly and cost several hundred dollars per month. They are violently expensive. I don’t actually believe that there are these shortages, I think that the makers are falsely causing the shortages to drum up hype and demand. There is no reason that they can’t make enough for everyone who would benefit from it and at a reasonable cost. This is a major marketing ploy!! Don’t fall for it