Vinay Prasad raises criticisms of Long COVID study methodology

Although there are a few issues with his analysis.

In following my Tuesday post raising criticisms of Long COVID studies, Dr. Vinay Prasad, along with a few other doctors, appeared to have released an article published in BMJ1 noting egregious issues in Long COVID study designs and methodology.

The article is an interesting read, tackling many of the issues that I have commented on, and including even more issues that I have overlooked such as the fact that many studies are test-negative studies. Remember that a test-negative study is one in which the “control” group is comprised of people who test negative for COVID, rather than one in which someone serves as a background representation for the general population (a test-positive study, in which case a person is included as a case when they test positive, but in this study design the control group isn’t one that necessarily gets tested to verify COVID status).

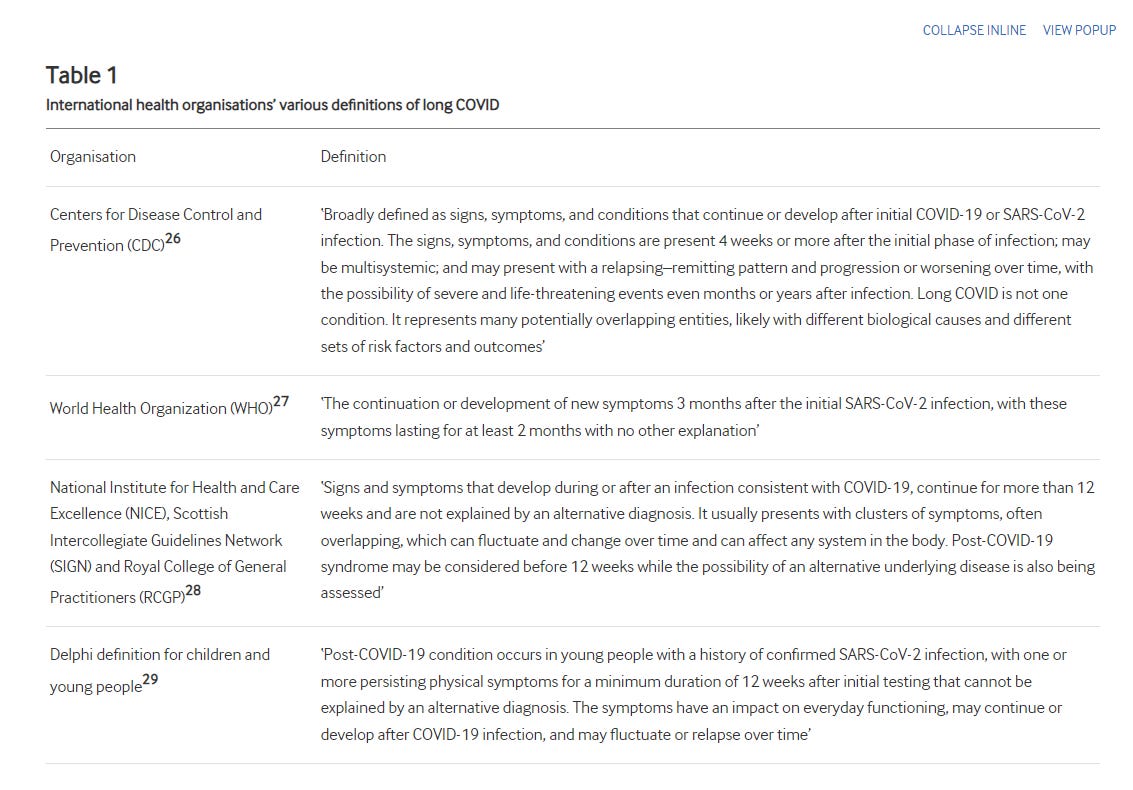

Further criticisms include nebulous case definitions for Long COVID, as well as inconsistent time periods between studies.

There’s also a huge issue in sampling bias, although this works both ways. A survey that recruits on the basis of the study being a Long COVID study is likely to bias both the case numbers as well as control numbers simply due to the fact that a person with any type of symptom may want to be recruited into such a study in order to get answers for whatever is plaguing them. This may mean a higher level of Long COVID patients relative to the general public, but it also may lead to a higher level of controls who test negative for prior SARS-COV2 infections but otherwise still present with one of the 12 symptoms. This has been one of my criticisms in which Long COVID surveys which report no statistically significant difference between groups are likely to capture a large group of controls.

Overall, I think the the review is worth a read. It’s short and details a lot of the epidemiological issues of this study.

Prasad, et al. ends the article with the following recommendations, as well as the following conclusion:

Ultimately, biomedicine must seek to aid all people who are suffering. In order to do so, the best scientific methods and analysis must be applied. Inappropriate definitions and flawed methods do not serve those whom medicine seeks to help. Improving standards of evidence generation is the ideal method to take long COVID seriously, improve outcomes, and avoid the risks of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Now, the article is a good run down for how researchers continue to miss the mark when trying to provide accurate data on Long COVID.

However, if I were to levy a criticism of this review (and Prasad in general), I have to raise criticism towards the fact that Prasad seems to overlook issues in studies if those studies conclude that Long COVID symptom rates are no different than the background rates of the general population.

It’s one of the reasons I wrote the following article in particular (apologies for essentially spamming this article):

Long COVID symptoms do not be downplayed for argumentative reasons

Modern Discontent is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Correction 6/1/2023: Below I remarked that the diagnostic cr…

Prasad took to suggesting that this study was a good reflection of the comparative rates of Long COVID symptoms in both positive and negative control groups.

The study is even mentioned in the BMJ review:

A more recent publication from Norway12 of children and young people aged 12–25 used a modified Delphi definition for long COVID (table 1) and found a strikingly high point prevalence of those meeting the case definition of post–COVID-19 condition and controls (the latter being SARS-CoV-2 seronegative) of 48.5% among SARS-CoV-2–positive cases and 47.1% in the control group, which was not significantly different.

In my article I mentioned several issues with this study, including the fact that the survey conducted included an initial survey and a survey 6 months out. It’s hard to get an accurate read of symptoms, especially in teenagers, with such a wide window between survey periods. There’s also the issue of ambiguity in the inclusion criteria for Long COVID symptoms:

Thus, a case/noncase assessment of PCC appears to depend on fitting at least one persistent symptom. When given such comments such as “experienced cough” a huge degree of subjectivity will be introduced.

Remember that these surveys were not conducted on a monthly basis post-infection, but were provided in a questionnaire 6 months post-recruitment and thus would require recall of these symptoms, leaving a serious degree of subjectivity in responses.

This is, unfortunately, a serious issue that has plagued nearly all Long COVID studies- the group that is intended to be measured is so broad and ambiguous that nearly all studies on Long COVID will capture comparable values in both positive and negative groups.

The at least one phenomenon in Long COVID studies is also something that needs to be addressed, and doesn’t appear to have been included in the BMJ article.

Suppose that, like with all kids, a teenager presents with fatigue. That’s one hit for a Long COVID symptom, and this kid, irrespective of prior infection history, would be considered within the Long COVID category. However, what if the teen goes on to get COVID, but instead of just fatigue the teen presents with periodic coughs and heart murmurs in the following weeks? Would a survey such as the Sevalkumar, et al.2 piece be able to capture this difference?

No, and that becomes an egregious issue with these studies, in which not only are the symptoms of Long COVID broad, but no study tends to provide a quantified measure of symptoms between positive cases and controls. By using an at least criteria for Long COVID, researchers are missing out on discerning whether or not a patient may be experiencing several symptoms rather than just fatigue or the occasional cough, and by not making this discernment it creates a false illusion that the percentage of of people experiencing Long COVID is all that matters, rather than the symptoms (which vary in severity) and the number of symptoms.

Unfortunately, this is also a predicament that will likely never be solved, as it would require a pre-pandemic baseline of symptoms in patients. I don’t think any doctors would have foreseen the pandemic and have known to create symptom definitions of Long COVID prior to the pandemic in order to gather baseline measures patients.

So there’s a bit more than what is being presented, and I have argued against some of the methodological issues in the Sevalkumar, et al. study.

But what’s probably more strange is the inclusion of ONS data, with the BMJ article citing the data as noting the ‘commonness’ of Long COVID symptoms in the population:

In the UK, national surveys conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) continue to report a 2.9% prevalence of self-reported long COVID in adults and children.21 Yet, when a control group was included with age, sex, health and socio-demographically matched controls, the prevalence of any of 12 common symptoms was 5.0% at 12–16 weeks after infection compared with 3.4% in a control group without a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, demonstrating the relative commonness of these symptoms in the population at any given time.23

The questionnaire uses an at least approach. It also required self-reporting, which itself has issues.

And when looking at the article from Citation 243 the word ‘commonness’ does appear in the main points part of the article:

Approach 1: Prevalence of any symptom at a point in time after infection. Among study participants with COVID-19, 5.0% reported any of 12 common symptoms 12 to 16 weeks after infection; however, prevalence was 3.4% in a control group of participants without a positive test for COVID-19, demonstrating the relative commonness of these symptoms in the population at any given time.

But what seems to have been left out was the fact that the ONS data was argued to suggest a statistically significant higher rate of Long COVID symptoms among COVID-positive people relative to control:

Among study participants with COVID-19, 9.4% reported any of 12 symptoms four to eight weeks after infection (based on responses from 15,061 participants), while 5.0% reported symptoms at 12 to 16 weeks (out of 12,611 participants) (Figure 1). These percentages were statistically significantly higher than in the control group, suggesting that the prevalence of symptoms following COVID-19 infection is greater than the background prevalence of these symptoms in the population at any given time. The difference in prevalence remained statistically significant at 20 to 24 weeks.

And so in this argued well-designed study, there appeared to be evidence of a statistically significant difference in Long COVID symptoms in those who tested positive with a prior COVID infection relative to those who never tested positive.

Now, I don’t bring this up to suggest that the ONS data is accurate. I don’t believe it to be given that it’s self-reported. However, I bring it up to point out that there’s more going on here than is reported in the BMJ article, and reading the article alone may present a false assumption that the prevalence of Long COVID in the population may be negligent and therefore not worth considering.

Now, I am not saying that Prasad, et al. are making that claim, but the problem is that this presentation makes it a bit difficult to argue that there’s a bit of a bias in reporting. Prasad, at least in my opinion, seems to have taken to refuting the prevalence of Long COVID in the general population by arguing comparative numbers between possible Long COVID patients and background, which may be a disservice for those who are actually suffering. It was one of my issues with his presentation of the Selvakumar, et al. piece in his original Substack article.

On one hand, the arguments made by Prasad, et al. and Prasad himself are reasonable. The fear of contracting Long COVID may induce a psychosomatic, stressful response in a subset of the population. It would be inadvisable for mainstream outlets and the CDC to report Long COVID rates if the data is highly inaccurate.

Worse, if the concept of Long COVID is weaponized to enforce masking and lockdown policies then there’s an even bigger incentive to criticize such Long COVID studies and dampen any paranoia that may extend from such reports.

However, doing so does not require that we downplay Long COVID, especially if it leads to the opposite effect, in which people who are experiencing Long COVID symptoms end up not getting the help they need because doctors refute the actual validity of these people’s symptoms. We certainly hope that this doesn’t happen to the vaccine injured, so it seems a bit disingenuous to do so to the COVID injured (I should note that I don’t believe this is Prasad’s argument- I’m speaking more broadly).

At the end of the day, we may come to find that no study on Long COVID will actually suffice. In the meantime, we can criticize reports of Long COVID without falling into the position of denying its existence outright. Care must be taken to not swing the pendulum of Long COVID in the other direction, much to the detriment for those who are suffering.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Høeg TB, Ladhani S, Prasad V

How methodological pitfalls have created widespread misunderstanding about long COVID

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine Published Online First: 25 September 2023. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2023-112338

Note that throughout this article I refer to this study as Prasad, et al. Although he is not the lead author, and this may be considered improper, he is more recognized and so it makes it clearer to readers what I am referring to. Also, any mention of the BMJ article references Prasad, et al. whereas any comment towards Prasad himself will just use his last name.

Selvakumar J, Havdal LB, Drevvatne M, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics Associated With Post–COVID-19 Condition Among Nonhospitalized Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e235763. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5763

Office of National Statistics.Technical article: updated estimates of the prevalence of postacute symptoms among people with Coronavirus (COVID-19 in the UK).2020.Available:https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/technicalarticleupdatedestimatesoftheprevalenceofpostacutesymptomsamongpeoplewithcoronaviruscovid19intheuk/26april2020to1august2021

Great analysis, thank you.

I have appreciated a few of Dr Prasad's videos critical of masking studies.

One aspect I always miss is, how many of the "Long COVID symptoms" are in fact 'just' "Long Illness symptoms". That is not to belittle these symptoms, but what is the difference between getting a severe flu case vs severe COVID. There seem to be some indication that some symptoms might be unique or at least more common after COVID (e.g. losing permanent partial smell capability), but for many others they sound to me 'just' common illness related. Every time one gets severely sick, especially as you age, it has a chance of more lasting effects. Again, that is not to belittle those affected, but only whether COVID is special.

That matters, as some people are still more afraid of COVID than let's say flu. But the question is whether that is warranted. That would only be warranted if COVID is more common to cause long symptoms or more likely to cause more severe symptoms. I personally am skeptical that is the case, and suspect if you would do a study on flu or RSV you'd find mostly similar long term effects, be it with some unique flavors.