To have the alpha-gal disease!

What exactly is this tick-derived disease that makes people allergic to meat?

Within the past few weeks I’ve seen several news articles or videos talking about the growing tick crisis. Well, crisis may not be the proper word, but there’s definitely been more talk about ticks, which may either be brought about due to the summer months or forces that may want us to stop eating meat.

Yes, with tick bites come a fear of becoming allergic to red meat, a rare and very strange disease called alpha-gal syndrome.

Normally I wouldn’t pay any mind to ticks. The image of swollen ticks is already disturbing enough already (I saw a news article about a rescued snake covered in ticks-wonderful!)

However, I saw a Notes thread where people were talking about alpha-gal syndrome, including a comment from Weedom asking about this disease, so I couldn’t help but be a bit curious and look at some of the information on what this syndrome is.

Most of the information will draw from one review in particular from Román-Carrasco, et al.1, so examine that review as well as other links for more information that may not be included in this overview.

Alpha-gal syndrome: an allergy to meat?

As perplexing as it sounds, there is a syndrome associated with tick bites that lead to an allergy towards red meat. This red meat allergy, called alpha-gal syndrome comes with a myriad of different symptoms after consuming red meat, including itchiness and hives, stomach pain, and other symptoms typical of an allergy. The most severe symptom is the onset of anaphylaxis, which can lead to death if not immediately dealt with.

AGS seems to be a result of repeat tick bites. Originally, AGS seemed to occur in those predominately within the South/Southeast part of the US, but as deer began migrating outwards from these regions they seem to have brought ticks, in particular lone star ticks, which have caused the disease to spread.

The name for this syndrome refers to a specific oligosaccharide found in tick saliva called galactose-α-1,3-galactose, and is likely where the alpha in alpha-gal is derived from.

This disaccharide (2-sugar molecule) is comprised of two galactose residues (hexose sugars), with the bonding between them coming from the C1 position of 1 galactose residue forming a glycosidic bond to the C3 position of the other galactose residue. The alpha refers to the orientation of the glycosidic bond.

This structure is then followed by another saccharide called N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), which altogether forms a trisaccharide (3-sugar structure). This trisaccharide is found on the surface of proteins and lipids in the form of glycoproteins and glycolipids.

What becomes interesting is where these trisaccharides are actually found. Aside from tick saliva, it appears that many mammals naturally produce these structures, with Old World monkeys, apes, and humans being the only few mammals seeming to not produce these alpha-gal structures. The reason for our lack of having these structures seems to come from a mutation at some point in our ancestral lineage which resulted in us losing the ability to produce these structures (Román-Carrasco, et al.):

Among vertebrates, the α-Gal epitope, Gal-α-1,3-Gal-β-1,4-GlcNAc, is only expressed on glycoproteins and glycolipids of mammals, whereas fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds do not produce this glycan moiety (70). Placental mammals, such as mice, cats, dogs, horses, cows, pigs, bats, New World monkeys or dolphins, as well as marsupials, such as opossums and kangaroos, all produce large amounts of α-Gal on all different kinds of cell types, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cell, epithelial cells, muscle cells and lymphoid cells (70). However, as mentioned before, there are a few mammals, namely Old-World monkeys, apes and humans, that lack the enzymatic machinery to synthesize α-Gal. Humans and animals (e.g., birds, fish) lacking α-Gal can produce antibodies against α-Gal (71).

Because of this loss of function it appears that we have gained the ability to become allergic instead. This also explains why man’s best friends of cats and dogs2, who may act as routine delicious meals for ticks, may not produce this allergic response- it’s likely during development that alpha-gal bearing mammals shut down any immune responses to these sugar structures so that they don’t produce an autoimmune response.

An IgE for red meat

As would be the case, it appears that we do produce an immune response against meat bearing this structure. Evidence seems to suggest that a range of 0.1-1% of our circulating IgG antibodies are targeted towards alpha-gal epitopes. In addition, IgM and IgA antibodies seem to be produced as well in order to target these structures.

It makes one wonder whether this antibody production bears some consequence on overall human health, although this may just suggest that we produce antibodies to many of the foods we eat in general.

Now, if we are already producing an immune response to these structures, how can a tick bite cause us to become allergic to red meat? The issue seems to lie in the production of IgE antibodies, which are antibodies more geared towards allergic responses.

After repeat tick bites, it appears that the antibody response is modified away from other classes of antibodies and towards production of IgE. Part of this effect is argued to be due to gaining resistance to tick bites, with the unfortunate consequence being that protection against tick bites may mean “protection” against red meats:

In contrast, the ability of humans to develop hypersensitivity reactions after repeated tick bites resembles the mechanism of acquired tick resistance (ATR) observed in several animal species (8). Thus, it was suggested that the α-Gal-specific IgE response in humans is an evolutionary adaptation associated with ATR and allergic klendusity with the trade-off of developing α-Gal syndrome. Allergic klendusity refers to a disease-escaping ability produced by the development of hypersensitivity to an allergen (8). Bell et al. (127) proposed for the first time that allergic klendusity was the immune property by which tick-sensitized rabbits developed resistance to tick-borne Francisella tularensis infection.

Another interesting reasons seems to relate to the tick saliva environment itself. Consider that, at the point a tick penetrates the skin and makes a meal of us and our pets, that the body’s natural response is to direct cellular responses towards repair and antimicrobial action.

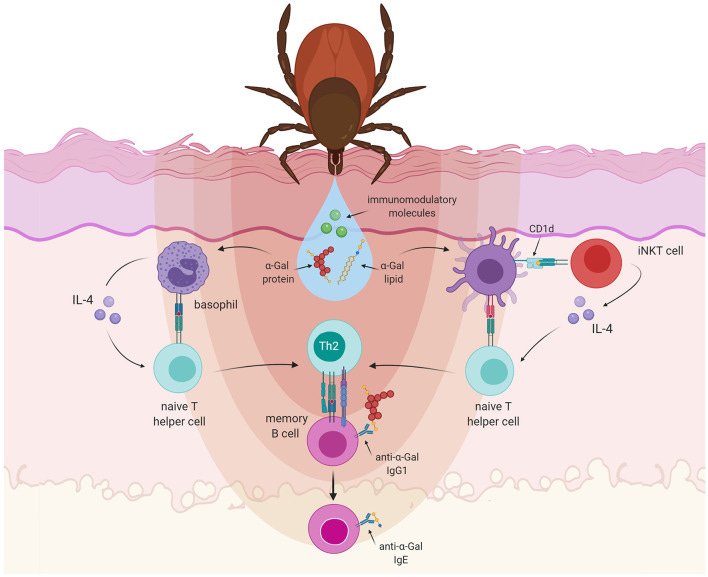

This wouldn’t bode well for the tick who would insists on feasting our blood, and so in response it appears that the tick releases a host of immunomodulatory compounds which alters the immune response so that it may keep feeding. However, by altering the immune response of our body it appears that we move more towards an IgE response against these tick bites by way of a Th2-directed response to these bites:

The saliva of ticks is a complex mixture of substances, several of them also with immunomodulatory properties. With the injury caused by the tick mouthparts that disrupt the epidermis and enter the dermis of the host skin, the mechanisms of wound healing begin in the host (132): coagulation, vasoconstriction, and platelet aggregation are followed by responses of the innate and adaptive immune system (133). For an effective blood feeding, the tick must be able to counteract the defense mechanisms of the host. Indeed, bioactive molecules present in the tick saliva can suppress the host's hemostatic as well as immune responses that impede efficient feeding (134) and that might damage the tick (135). Tick saliva has been shown to decrease the production of the proinflammatory mediators IL-12, IL-1β or TNF-α (132), while promoting an increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines like TGF-β or IL-10 (136). These effects might be mediated by molecules such as Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which is very abundant in tick saliva. PGE2 induces vasodilation and impairs wound healing while reducing inflammation (137). Furthermore, in mice infested by ticks high TGF-β levels have been observed, together with increasing amounts of IL-10 and IL-4 after every exposure to ticks (136). This suggests that repeated exposure to tick saliva could skew the polarization of the immune response toward a Th2 profile, which induces the development of allergies and suppresses a pro-inflammatory Th1 response (135) (Figure 3).

There’s a lot going on here, and I kept it a bit simplified aside from the excerpt taken from Román-Carrasco, et al.

In short, many animals appear to produce alpha-gal epitopes, and we as humans seem to produce an immune response to these epitopes. However, the nature of a tick bite converts our immune response to an allergy-dominated response. Paired with the cross-reactivity of alpha-gal bearing structures in tick saliva, and our body no longer can tolerate meats from animals who produce these epitopes.

It’s a very strange series of events, and one that seems more perplexing than it would initially appear. Personally, I find all of this to be very interesting, if not a bit sad to think about losing the ability to eat steaks.

What’s the sensitizing event?

What remains to be determined is the series of unfortunate events that leads to a red meat allergy. This complication seems to be derived from the fact that several strains of gut bacteria appear to produce alpha-gal, or at least bear genes that encode for enzymes that produce this epitope. This may explain some of the antibody responses of IgA, which are antibodies usually found on mucosal surfaces.

Given this revelation it has become an issue in figuring out whether a tick bite is the sensitizing event, or whether responses to gut microbes may facilitate a sensitizing event, with the tick bite causing the allergic response that further leads to alpha-gal syndrome. There’s much to the gut microbiome’s role in this disease that appears controversial. A study from 2022 examining the expression of alpha-gal on the surface of different gut bacteria using monoclonal antibodies didn’t appear to find any evidence of binding, suggesting that the gut bacteria tested may either not express this epitope or that the expression may be masked by other structures, and therefore are not recognized.3

So even as researchers seem to have an understanding of how alpha-gal forms, there still remains several questions about the lead-up to the tick bite that have yet to be determined.

Some more on alpha-gal syndrome

As summer continues to blast on, it may be worth taking some time and avoiding the ticks if possible.

But aside from engaging in tick-avoidance, here’s a few bits of information about alpha-gal syndrome that I find rather interesting:

The allergic response for AGS is delayed, usually taking hours after consuming red meat before symptoms may arise. Part of this seems to be due to the route in which the alpha-gal epitope gets recognized. Alpha-gal seems to be expressed in lipids as well, which are digested and metabolized differently compared to protein. Therefore, kinetics may dictate this delayed response.

Different meats appear to produce more severe reactions. Fattier pieces may contain more alpha-gal. It also appears that some organ meats may as well, and evidence suggests that people experience the most severe allergic reactions when ingesting fattier cuts of meat or the innards/organs of animals.

Note that some drugs may contain alpha-gal, including some animal-derived monoclonal antibodies such as Cetuximab and Infliximab. It actually seems that the use of Cetuximab, which bears this epitope as part of the Fab portion of the antibody, was what led to the discovery of AGS when clinicians noted a hypersensitive reaction in those given Cetuximab for colon cancer.

Remember that soups, sauces, or other foods that may be sourced from mammals are likely to contain alpha-gal, and so people diagnosed with AGS should take care to consider any foods possibly derived from mammals.

Strangely, the consumption of gelatin for those with AGS has been controversial, with some patients appearing to tolerate low amounts of gelatin. Therefore, it’s likely that this response is complex, and may be related to dosage and type of alpha-gal product.

In a rather morbid sense, I suppose that this would mean that people with AGS can consume human flesh, although I guess whether or not that person has eaten red meat beforehand should also be considered (isn’t human meat red meat?). Maybe before one thinks about eating their neighbor in the end of times try your local zoo’s gorilla. The meat may be more tender anyways due to being in captivity…

Snake venom contains alpha-gal epitopes, and so there appear to be various routes of exposure that may cause an allergy to develop. One of the reasons why we don’t really hear about snake venom-derived AGS is likely due to a numbers game. People are likely to be more at risk of being bitten by ticks than they are venomous snakes. Tick bites, aside from the possibility of obtaining Lyme disease, are not lethal for the most part as well, which cannot be said for venomous snake bites. It’s not as if people are at risk of repeat snake bites in general, and so it may just mean that ticks are the most likely mode of AGS formation.

I guess this should also raise some questions about this so-called snake venom hypothesis of COVID…

Alpha-gal epitopes are one of the reasons why organ transplants from other animals have failed (called xenotransplants), as our bodies launch an antibody response against these epitopes.

Additional articles for those interested:

Platts-Mills, et al.4: Diagnosis and Management of Patients with the α-Gal Syndrome.

Wilson, et al.5: Atypical Food Allergen or Model IgE Hypersensitivity?

Hilger, et al.6: Role and Mechanism of Galactose-Alpha-1,3-Galactose in the Elicitation of Delayed Anaphylactic Reactions to Red Meat.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Román-Carrasco, P., Hemmer, W., Cabezas-Cruz, A., Hodžić, A., de la Fuente, J., & Swoboda, I. (2021). The α-Gal Syndrome and Potential Mechanisms. Frontiers in allergy, 2, 783279. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2021.783279

I won’t discriminate here, but people can fight in the comments section all they please over who is actually man’s best friend.

Kreft, L., Schepers, A., Hils, M., Swiontek, K., Flatley, A., Janowski, R., Mirzaei, M. K., Dittmar, M., Chakrapani, N., Desai, M. S., Eyerich, S., Deng, L., Niessing, D., Fischer, K., Feederle, R., Blank, S., Schmidt-Weber, C. B., Hilger, C., Biedermann, T., & Ohnmacht, C. (2022). A novel monoclonal IgG1 antibody specific for Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose questions alpha-Gal epitope expression by bacteria. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 958952. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.958952

Platts-Mills, T. A. E., Li, R. C., Keshavarz, B., Smith, A. R., & Wilson, J. M. (2020). Diagnosis and Management of Patients with the α-Gal Syndrome. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 8(1), 15–23.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.017

Wilson, J. M., Schuyler, A. J., Schroeder, N., & Platts-Mills, T. A. (2017). Galactose-α-1,3-Galactose: Atypical Food Allergen or Model IgE Hypersensitivity?. Current allergy and asthma reports, 17(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-017-0672-7

Hilger, C., Fischer, J., Wölbing, F. et al. Role and Mechanism of Galactose-Alpha-1,3-Galactose in the Elicitation of Delayed Anaphylactic Reactions to Red Meat. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 19, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-019-0835-9

I'd say it would be more worrisome when the alpha gal is your wife! LOL

I could be oversimplifying but IgE essentially is part of an immune "extended use or exhaustion" signal.

So evolutionarily we have the antibody response to meat as a protective mechanism (meat from kills left out, not cured correctly, poisioned, etc), so in a sense, our immune system treats it as a possible source of infection, then turns it down when it's deemed "safe". But because of this, too much can also trigger inflammatory activation, hence why ultimately carnivore diets in the long-term show detrimental effects immunologically and increased aging. Small amounts can be beneficial, while as always the dose makes the poison. BTJMO.😉🤷♀️

My understanding of the lone star tick specifically, is that it was a gain of function accident, based on Mikovits book.