The hospital/microbiome paradigm

How does the precarious nature of a hospital help/hurt the microbiome?

The following, like all articles, is an opinion piece intended to add further context to the role of the microbiome as it relates to a hospitalization. This information is intended to serve as food for thought, and certainly not as medical advice, so please consider the proceeding article as intending to be informative and not prescriptive.

It’s well known that the hospital protocols for COVID patients have been heavily scrutinized, with several articles online having headlines akin to “hospital protocols killed patients”.

Because of these concerns it’s worth examining hospital dynamics with respect to the microbiome.

Sprinkled throughout the previous microbiome posts were comments with respect to the hospital’s role in these secondary bacterial infections.

It’s possible that many secondary infections are acquired by community spread, but it’s also very possible that the hospital contributes to infections as well.

Indiscriminate antibiotic use, poor nutrition, and nosocomial infections through the interventions used in hospitals all contribute to the deterioration of patients.

Note that nosocomial infections have been considered by several to be some of the top leading killers here in the US.1

This begs the question: how much does a hospital stay contribute to the worsening of COVID patients?

Note that this post will not answer these questions, but provide further context to the factors related to nosocomial infections in COVID patients and the role that the microbiome plays in these outcomes.

To antibiotic, or to probiotic

One obvious method used to curtail secondary infections in COVID patients is to provide a sterile environment: if you get rid of all pathogens, the patient should be kept safe, right?

But let’s consider the article from Carrier Arnold2 cited previously which remarks on rethinking sterility within a hospital setting:

Today, antibiotic-resistant infections show no signs of stopping, nor do hospital-acquired diseases.3Historically, these infections have been blamed on the presence of harmful bacteria, and increasingly stringent infection-control procedures and standards for sterility have been seen as the solution.5 A new hypothesis says that hospital-acquired infections are being driven not by the existence of harmful microbes but by the absence of helpful species.

Underneath the bright lights and on the stainless steel gurneys lives a large community of microorganisms, most of which are harmless and some potentially beneficial.6 Hospital microbiomes, some researchers think, form a key part of a hospital’s “immune system” and in some cases may help protect patients against infectious diseases.

“For the past 150 years, we’ve been literally trying to just kill bacteria. There is now a multitude of evidence to suggest that this kill-all approach isn’t working,” Gilbert says. “We’re now trying to understand that maybe, just maybe, if we could cultivate nonpathogenic bacteria on hospital surfaces, then we could see if that would lead to a healthier hospital environment.”

Human microbiome research has shown that the use of antibiotics can disrupt the normal array of microbes that live in and on our bodies.7 The constant attempts at sterilization in hospitals might function on a similar level—the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, bleach, and hand sanitizer might take out some of the harmful pathogens, but it also cuts a swath through the hordes of nonpathogenic microorganisms.

Attempts to sterilize the hospital environment have proven to provide opportunities for resistant bacteria to bloom among the surfaces of equipment. This may also stem from rampant use of hand sanitizers and other antimicrobial products that may select for resistant bacteria among the staff as well, which can then spread to compromised patients.

As mentioned in the bacteremia article, it’s possible that bacteremia in COVID patients may stem from intravenous catheter use, which may provide a route for skin commensal bacteria into the blood of patients, possibly playing a role in sepsis.

For patients on ventilators, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) may be common and is associated with poorer outcomes in patients.3

The risk of infection for hospitalized patients may cause doctors to take a preventative approach and prescribe antibiotics prophylactically to inpatients.

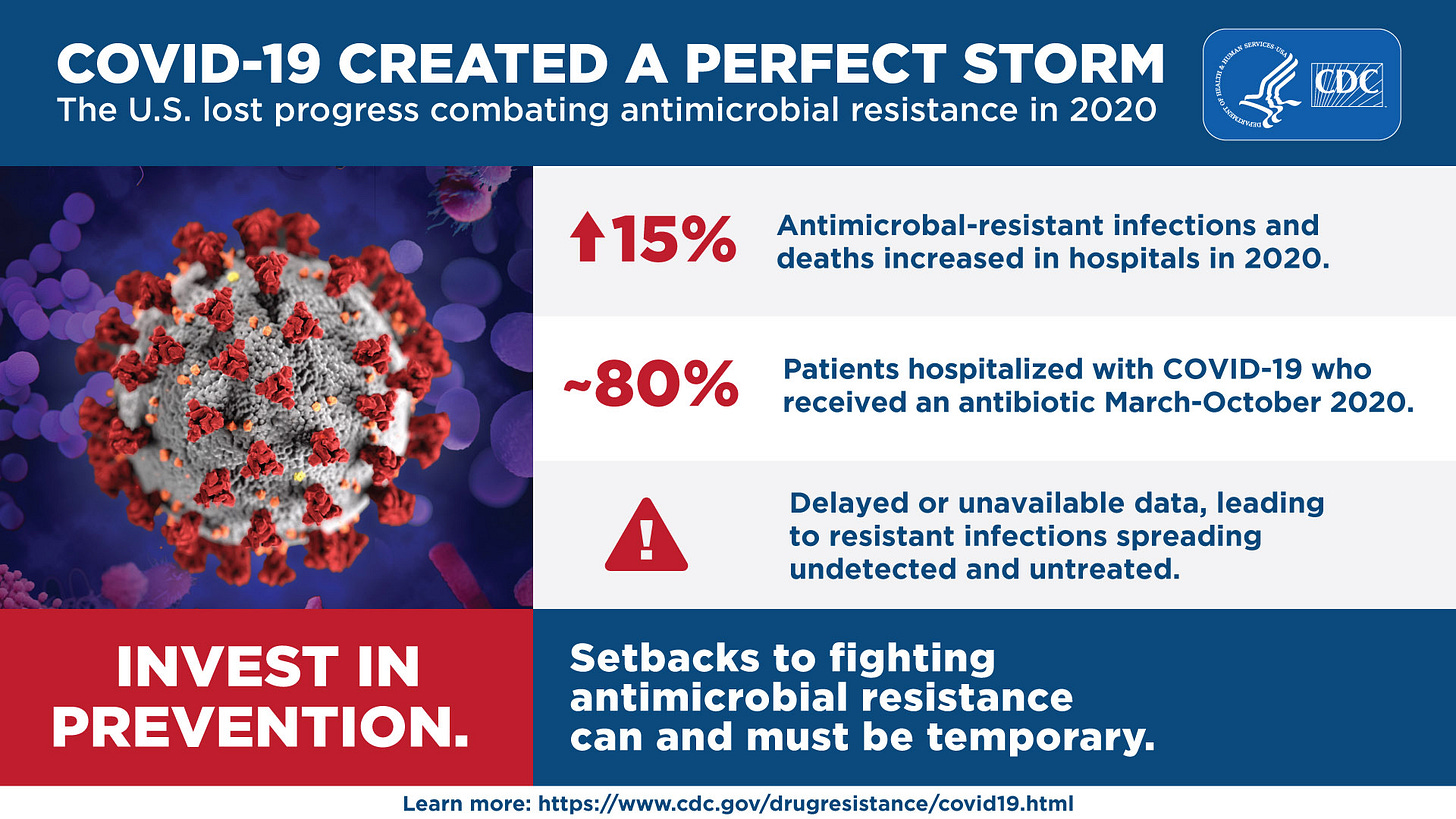

A CDC report from June 2022 suggests that antibiotic use during the early months of the pandemic could have been as high as ~80%, and likely contributed to the increase in antimicrobial-resistant infection in hospitalized patients.

Remember to take such metrics with a grain of salt, as the use of antibiotics would vary greatly depending on a hospital’s own policies in dealing with SARS-COV2. The initial guidelines from the CDC also raise some hesitancy in prescribing antibiotics unless diagnostic tests confirm a possible infection, or there is suspicion of bacterial pneumonia/sepsis in patients.

Remember too that several patients were prescribed Hydroxychloroquine in tandem with Azithromycin, an antibiotic, and may serve as a contributory factor for hospitalized patients.

Regardless, the use of antibiotics comes with serious concerns. If a patient doesn’t have an actual infection, the use not only will prove futile but will also damage the microbiome of the patients.

As the microbiome itself acts as a defensive barrier4, the untimely use of antibiotics may inherently erode the protection and make patients even more susceptible to secondary infections. That also comes as the alterations to the host’s microbiome also reduces the ability to deal with inflammation and may make the cytokine storm even worse.

So this raises a critical question: if antibiotics may come with serious concerns, would the use of probiotics be better for patients?

That is to say, should a probiotic approach be taken to help improve outcomes in hospitalized patients, rather than an antibiotic one?

Several researchers have wondered whether a probiotic approach may be more beneficial as a way of maintaining commensal bacteria during times of disease and trauma.

In particular, several studies have examined probiotics as a preventative tool in curbing diarrhea caused by Clostridioides difficile5; a common consequence of antibiotic use.

Rather than have to deal with C. difficile, would the use of probiotics help to restore the altered microbiome and prevent infection of opportunistic bacteria? This question may also extend to other prophylactic use in other interventions as well.

Unfortunately, this assumption may be easier said than done.

Some studies have suggested that prophylactic probiotics may be beneficial to patients. Of note, several reviews looking at probiotic use in mechanically ventilated ICU patients suggest that probiotics may help reduce the risk of VAP.6,7

However, it’s worth noting that these results tend to be mixed, likely owed to low sample sizes in various RCTs, the specific strains of bacteria in probiotic used, and the disease in question.

But here there is, once again, a balancing act. As SARS-COV2 alters the gut microbiome and makes it more permeable, the use of probiotics may not be beneficial, and may actually contribute to bacteremia as the bacteria from probiotics may easily escape into a patients bloodstream.

A review from Katkowska, et al.8 notes several cases in which probiotic use were noted to lead to bacteremia with those specific strains in the provided probiotics, as well as other adverse outcomes such as infection due to the bacteria behaving more as opportunistic agents rather than commensal support.

This creates a serious conundrum for clinicians. As evidence mounts to indicate the significance of the gut microbiome, and given all of the different microbial interactions a hospitalized patient must deal with one may question what the practical response is.

Is it better to prescribe antibiotics and hope that resistant bacteria may not bloom and overwhelm the patient, or should a proactive, probiotic approach be taken given the limited data and the possibility for the probiotic to lead to its own adverse events?

Hospital malnutrition and lack of prebiotics

Like all of us, our microbiome is living, and therefore requires sustenance for their survival.

Nutrients needed to sustain a healthy microbiome are referred to as prebiotics, which may include various plant compounds especially dietary fiber.

Unfortunately for many hospital patients, hospitals aren’t well-known for having nutrient-dense foods, with many cafeterias likely focusing on reduced salt intake for patients as being more important. This may lead some patients to seek out unhealthy foods as they receive care, which of course would spell trouble for these patients.

Indeed, it’s known that hospitalized patients may suffer from malnutrition, leading to worse outcomes and possibly may contribute to mortality.9

Several studies have also pointed to increased risk of malnutrition in hospitalized and ICU COVID patients.10

In more critically ill patients who may be unable to feed themselves other methods of providing nutrients may be used such enteral feeding, in which a feeding tube is brings an enteral formula into the stomach of patients.

Enteral formulas are designed with macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals in mind11, but they may only serve as verisimilitudes of actual foods, as many likely lack some of the other vital nutrients from whole foods.

There’s also the fact that nutritional needs would differ among patients who may require additional supplementation, and that many patients may not be cared for properly while in the ICU and may be underfed.

Most notably, lack of dietary fiber (both soluble and insoluble), a critical prebiotic for beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium to ferment into short chain fatty acids, would also influence the makeup of the gut microbiome and encourage a pro-inflammatory response.

Strangely, even as more attention is being given to the microbiome many healthcare policies and nutritional guidelines may not be catching up to the same degree, as the addition of fiber for ICU patients still appears to be a controversial opinion.12

No study appears to have been done to correlate dietary fiber intake and severity in COVID patients, although the literature tends to point towards there being a large degree of malnutrition in COVID patients regardless, which may influence outcomes.

So how a hospital manages such specific nutritional requirements is worthy of examining, as it’s quite likely that the inability to provide whole, nutrient-dense foods to patients may play some role in patient outcomes.

Of course, how one would go about doing so is another matter, and it brings up the point of whether patients would even be able to properly digest the foods without suffering from adverse complications such as bloating or vomiting.

But regardless, it doesn’t remove the fact that lack of nutrition is a key component of patient outcomes.

What to do about the microbiome

By the time a patient reaches a hospital it becomes a literal do or die moment for clinicians.

As hospital protocols have come under serious scrutiny, it raises questions as to what approach hospitals should take in helping patients recover and avoid serious illness.

Here, we took a glance at interventions with respect to the microbiome. It’s clear that the microbiome is critical to our overall health, but what exactly can be done for hospital patients?

In summary, antibiotic use may prevent illness from pathobionts or bacteria which may enter through intravenous catheters, feeding tubes, or mechanical ventilators. However, these same bacteria are likely to become heavily resistant to antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents, which would make treating them even more difficult.

Rather than take an antibiotic stance the use of probiotics may actually help improve the deteriorating gut and lung microbiome as the SARS-COV2 infection persists, as some studies have suggested a benefit in the use of probiotics for patients hospitalized for other reasons. However, if the gut has been compromised to a severe degree, it’s possible that the probiotics may actually translocate into the blood and become pathogenic themselves.

And that comes with the fact that nutrition is likely to have drastically changed once someone enters the hospital, which itself may contribute to the declining state of the patient.

No matter which way someone looks at it, the hospital is not likely to provide an environment conducive for microbiome health.

Now, let me be clear that this doesn’t mean that the hospital should be avoided. However, what it means is that maintaining a healthy microbiome should be critical in avoiding having to go to a hospital as a healthy, homeostatic microbiome may help reduce risk of severe infection while helping improve overall health.

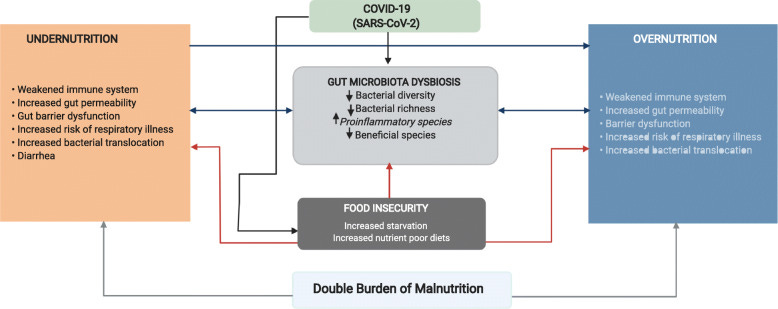

It’s quite clear that the increase in obesity over the past few years has not helped our guts, especially given food shortages, increasing prices, and the increase in takeout and fast foods that have damaged our guts and made us more susceptible to all kinds of illness.

Littlejohn, P., & Finlay, B. B.13 refer to this situation as the double burden of malnutrition and outlines this scenario below:

As the discussion so far in many of these posts have looked at how our microbiomes can become damaged, it’s worth looking at ways in which we can repair and maintain a healthy microbiome.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Liu, J. Y., & Dickter, J. K. (2020). Nosocomial Infections: A History of Hospital-Acquired Infections. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America, 30(4), 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2020.06.001

Arnold C. (2014). Rethinking sterile: the hospital microbiome. Environmental health perspectives, 122(7), A182–A187. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.122-A182

Giacobbe, D. R., Battaglini, D., Enrile, E. M., Dentone, C., Vena, A., Robba, C., Ball, L., Bartoletti, M., Coloretti, I., Di Bella, S., Di Biagio, A., Brunetti, I., Mikulska, M., Carannante, N., De Maria, A., Magnasco, L., Maraolo, A. E., Mirabella, M., Montrucchio, G., Patroniti, N., … Bassetti, M. (2021). Incidence and Prognosis of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Multicenter Study. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(4), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040555

Khan, R., Petersen, F. C., & Shekhar, S. (2019). Commensal Bacteria: An Emerging Player in Defense Against Respiratory Pathogens. Frontiers in immunology, 10, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01203

Valdés-Varela, L., Gueimonde, M., & Ruas-Madiedo, P. (2018). Probiotics for Prevention and Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1050, 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72799-8_10

Li, C., Lu, F., Chen, J., Ma, J., & Xu, N. (2022). Probiotic Supplementation Prevents the Development of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia for Mechanically Ventilated ICU Patients: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in nutrition, 9, 919156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.919156

Sun, Y. C., Wang, C. Y., Wang, H. L., Yuan, Y., Lu, J. H., & Zhong, L. (2022). Probiotic in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients: evidence from meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC pulmonary medicine, 22(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01965-5

Katkowska, M., Garbacz, K., & Kusiak, A. (2021). Probiotics: Should All Patients Take Them?. Microorganisms, 9(12), 2620. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9122620

Hiesmayr, M., Tarantino, S., Moick, S., Laviano, A., Sulz, I., Mouhieddine, M., Schuh, C., Volkert, D., Simon, J., & Schindler, K. (2019). Hospital Malnutrition, a Call for Political Action: A Public Health and NutritionDay Perspective. Journal of clinical medicine, 8(12), 2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122048

Feng, X., Liu, Z., He, X., Wang, X., Yuan, C., Huang, L., Song, R., & Wu, Y. (2022). Risk of Malnutrition in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(24), 5267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245267

Iacone, R., Scanzano, C., Santarpia, L., D'Isanto, A., Contaldo, F., & Pasanisi, F. (2016). Micronutrient content in enteral nutrition formulas: comparison with the dietary reference values for healthy populations. Nutrition journal, 15, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0152-2

Green, C. H., Busch, R. A., & Patel, J. J. (2021). Fiber in the ICU: Should it Be a Regular Part of Feeding?. Current gastroenterology reports, 23(9), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-021-00814-5

Littlejohn, P., & Finlay, B. B. (2021). When a pandemic and an epidemic collide: COVID-19, gut microbiota, and the double burden of malnutrition. BMC medicine, 19(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-01910-z

A very dear & sweet older gentleman with whom I attended church passed away recently after a bad UTI which turned into MRSA after an extended hospital stay. Indeed it definitely shows how bacteria can get a foothold and overrun our bodies. With so much advertising spent on disinfecting & terrifying the masses over “germs” it’s no wonder we end up in such predicaments. It’s almost like we’re trying to go full circle ... we’ve got sewage sanitation & proper food storage techniques but we somehow think sterility is the goalpost when that is almost just as bad as abject filth.

How about that bariatric surgery????

So many of those patients come in with anemia, low albumin and so on…. I bet those Roux-en-Y, etc. surgeries are a disaster for the microbiome. It’s also true that a lot of obese patients show signs of malnourishment in their labs.