There’s been a lot of discussion in recent days relating to RFK Jr.’s appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast, and the ensuing “fallout” outlined by many news outlets.

I haven’t watched the episode yet, but I generally assume that the presentation is one of open dialogue, drawn out over several hours which allow ideas to either flourish or fester based on how the conversation flows. It’s one of the most fascinating, and much-needed approaches to dialogue now, as long-form podcasts such as Joe Rogan’s allows his guests to either sink or swim when provided enough time. It’s why his podcast does so well, especially at a time when TikTok and YouTube Shorts enforce a constant dopamine hit with extremely short videos that only serve to enforce ever-shorter attention spans and cheap reward mechanisms.

But this apparent discussion has led to widespread criticisms of Joe Rogan for even daring to provide RFK Jr. a platform, including one Dr. Peter Hotez who was a guest on Joe Rogan’s podcast during the pandemic.

Dr. Hotez appears to have taken it upon himself to rebut the interview, landing him in an awkward position in which RFK Jr., with the support of people such as Elon Musk and Joe Rogan himself, has asked for a debate with Dr. Hotez.

Many people have commented on this situation, so it’s quite clear that there’s a lot of attention and interesting being brought to this issuance of a debate.

I’ve thought about this for a bit, and I suppose that my ideas differ a bit relative to what I’ve seen, and this comes down to what exactly is earned by debating, and is the intent of a debate really just to “win”?

How do you “win” a debate?

If we consider political discourse, the intent of a debate may be to win against an opponent. That’s how debate works in high school and college debate, even on topics that are not inherently political. In this case, the intent of a debate is to essentially gamify an issue or topic, and in doing so relegates it to a position in which the overall intent is to appear to win, rather than to focus on the substance of the topic.

A while back I heard comments that debate clubs and tournaments have changed from what is was years ago. I was on the debate team during my senior year of high school, but that was just to add some padding to college applications- I certainly wouldn’t consider myself good at debate myself (I think I “won” only once that year, and barely). In those days the debate focused on the topics, and the ability to produce a cogent argument (hence my issue).

But in seeing some of the discussions over modern debate, it appears that the new tactic is not one of substance, but one of presentation. That is, talk fast and incoherently in order to gain more points over your opponent, irrespective of whether there is anything meaningful to what is being presented. Quantity over quality as it appears. This may explain why so many debaters on YouTube, especially so-called left-leaning, philosophy YouTubers seem to talk fast even if there isn’t much to what they are saying.

And yet even now the approach to debate seems even more removed from actual topics, and instead focuses on ad hominems.

Consider a rather timely article from The Free Press:

As James Fishback reports, one doesn’t even need to talk about the debate topic; just look through your opponent’s social media profiles and make that the point of contention. That appears to be the case for one high school debater Matthew Adelstein:

Adelstein told me that, in April 2022, he competed at the prestigious Tournament of Champions in Lexington, Kentucky, where he debated in favor of the federal government increasing its protection of water resources.

In his final round of the two-day tournament, Matthew was shocked to hear the opposing team levy a personal attack against him as their central argument. The opposing team argued: “This debate is more than just about the debate—it’s about protecting the individuals in the community from people who proliferate hatred and make this community unsafe.”

Suffice it to say, Adelstein appeared to have lost that round, as his misinterpretation of a tweet landed him in the spot of being considered a bigot, which was enough to warrant a win for his opponent.

Read the article from Fishback for more on this apparent issue, as it appears that many debate judges have taken to using a debater’s personal life as a way of marking marking them down, irrespective of the relevancy to the debate topic.

In this case, what Fishback presents is a glaring issue in how we perceive debates, especially under the guise that debates should allow a side to “win”. In political discourse, this approach may seem feasible, and is in fact a staple in elections. This is why we allow mudslinging, no matter how egregious this can be. It makes for good entertainment such as the debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.

However, within the realm of science the concept of debate shouldn’t be contingent upon the idea of winning. Science has always been open to discourse, and scientists are allowed to provide whatever argument they deem feasible so long as they back it up with evidence.

It’s the evidence that matters, and we may argue that the weight of one’s argument is what allows certain ideas to prevail, rather than the need to win by all means necessary.

What I would argue is that science has become too politicized, and thus it has become gamified, especially within the realm of a debate. You don’t have to rely on facts and evidence, and you apparently don’t even have to stay on topic. Just leverage an attack against your opponent, argue loosely that they are acting unscientific (whatever that means), suggest that they are not an expert (again, what does that mean?), and you can supposedly “win” a scientific debate, evidence be damned!

In that regard, the winnable nature of a debate becomes entirely subjective, and becomes far removed from the actual substance that should feed a debate.

Rather, if both sides present what they deem to be the best evidence for their argument, then viewers/readers would be allowed to stew on the evidence and form their own conclusions, all the while hopefully becoming more informed and more perceptive of the different viewpoints.

Unfortunately, gamification means that we are more inclined towards arguments based on who is presenting them, how we perceive these individuals, and how they come across- all things that are tangential to the actual issues presented.

So if we argue that debates should be won, we should look at how we perceive a “win”. If no evidence is provided, is the need to win really all that necessary? Because if viewers/readers are not made more informed, then what exactly would be the intent of a win?

Enforcing echo chambers

Many years ago many millennials’ childhood idol Bill Nye entered into a debate with Ken Ham over the topic of evolution vs creationism.

As of now, the debate has over 10 million views. It’s been years since I have viewed it so I can’t recall much of the details aside from a few of the responses after the debate.

In general, I’ve grown up agnostic, and so I leaned more towards Bill Nye’s side of the argument, although now I’d consider there to be a lot more nuance over the evolution vs creationism debate, especially over the fact that one may not even need to argue these ideas as being wholly separate.1

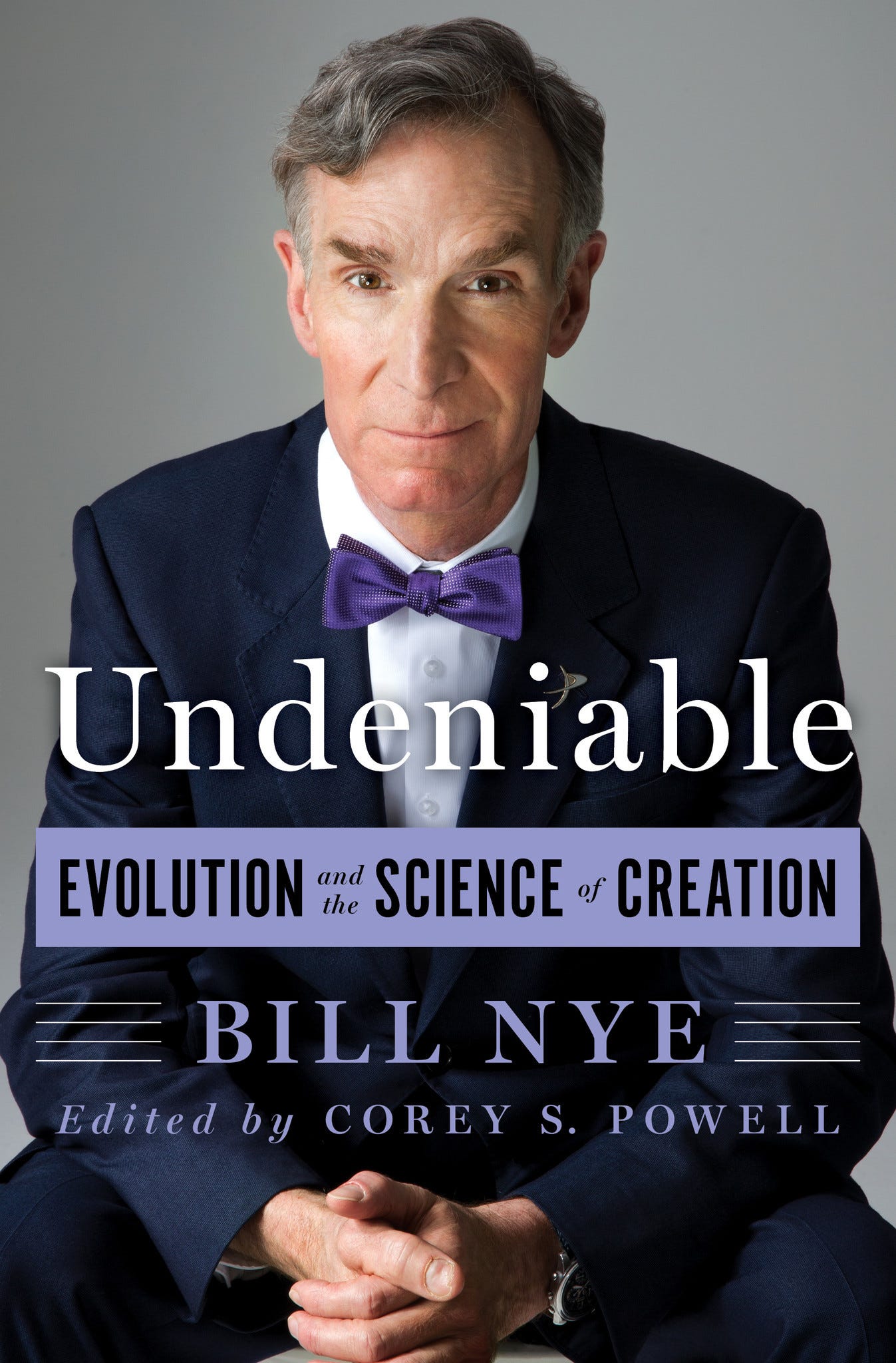

In any case, many evolutionary-minded people deemed this debate as a slam dunk, and Bill Nye seemed to have taken a victory lap over this debate, eventually releasing a book on the “undeniable” concept of evolution:

I was actually excited for this book since I thought it would further elaborate on Bill Nye’s position, but unfortunately my library didn’t have any copies available for months.2

Strangely, after finally getting a copy and reading the book, I became a bit disenfranchised. I actually couldn’t finish it when I first took it out, and had to keep renewing it (which makes me wonder if this happened with others as well).

Was it because the book was dense and full of clear examples of evolution?

No, and rather on the contrary, as I recall the book as being rather redundant and vacuous. That is, many of the topics seemed to rely on the “well, clearly evolution is occurring! You just need to look around!” form of presenting the argument.

I don’t know if this was one of the points that I began having a falling out with Bill Nye, or maybe it was his self-aggrandizing show which contradicted everything he initially stood for. I wasn’t a super big fan of him in any case and just remember him since we watched his videos a lot growing up.

But in any case, the point of this example is to elaborate on the fact that substance can sometimes be missing from a debate. More importantly, if the debate invokes one’s viewpoints, we may be more inclined to agree with the position irrespective of the evidence presented. It was really only after reading Bill Nye’s book outside of the context of a debate that I realized Bill Nye may not really offer much in the way of conceptualizing evolution.

I won’t say that this means that evolution doesn’t exist, but more that Bill Nye just served more as a mouthpiece with not much to add to the actual discourse. In a space where he should be able to elaborate, I don’t recall him elaborating, and yet he has been deemed as the talking head of evolutionary theory.

So when we look at a debate, we may easily fall into the false premise that a debate may inform readers/viewers, rather than serve as a doubling down on one’s already ossified position.

Consider those who want RFK Jr. to debate Dr. Hotez- it’s likely that these people are already heavily critical of both the COVID vaccines and vaccines as a whole- their perspective is already one in which RFK Jr. has taken the “right” stance on the subject matter, and will not be swayed irrespective of the evidence provided to the contrary.

And the same can be said for Dr. Hotez, who many vaccine zealots may consider have taken the right stance on vaccinations and see his recent remarks as emphasizing the benevolence of vaccines in contrast to RFK Jr.’s allegedly conspiratorial position.

Once ossified, it’s hard for people to look for other viewpoints, especially if it contradicts their worldview.

But then that begs the question of who will be swayed by the evidence, and who would actual walk away from a debate feeling more knowledgeable?

The problem is that both sides, in this paradigm of othering opponents, has essentially created insular groups in which no one looks to seek out contrasting viewpoints. Rather, the language that gets used doesn’t do much to encourage differing opinions, and what we deem to be the playbook of opponents may rely on strawman arguments because we dare not to engage with opposite perspectives to see what they actually think.

I have tried to avoid any mention of “clot shots” or “gene therapy” in my writing because I don’t find them useful if one were to persuade others that the COVID vaccines are harmful. If you’re already dealing with someone who argues that the vaccines are beneficial, are you really going to win them over by shouting “CLOT SHOTS!” at them? I highly doubt that, and you’re more than likely to just cause these people to not even dare to see the viewpoints of COVID vaccine critics because of how crazy they may seem.

This also doesn’t take into account that this language also causes confusion. I am reminded of a video presentation a reader provided me (apologies for not remembering who) in which Dr. Ryan Cole was presenting at a meeting with respect to these vaccines, with every castigation of the vaccines being met with applause by the audience. I remember that he kept calling these vaccines “clot shots”, and yet when talking about the adverse reactions in young children he emphasized the high rates of myocarditis, not blood clots.

These are all true in some regard (the vaccines are causing microclots and other severe forms of thrombosis in several individuals, and several people have clear evidence of myocarditis post-vaccination), but would a bystander be able to look at this presentation and discern what is meant by the language? If someone mentions “clot shots” in one breath but then mentions myocarditis in another, how does one interpret this information? Do we infer that one causes the other, or that these two are distinct pathologies related to a similar causative agent?

Again, when I see such a presentation I have to consider who these presentations are for. If for COVID vaccine critics, then this just emphasizes something that everyone on “this side” of the argument are already aware of. Vaccine zealots are likely to pay no mind, and those who are agnostic or willing to see other viewpoints may just be left confused and more inclined to argue that these individuals are just crazy.

All this to say, debates don’t serve much outside of ossifying one’s position. The language that gets used, and the manner in which a debate is conducted, is likely going to cause people to double down rather than to be open-minded. It’s why we can see both sides, even prior to a debate, already arguing that their position is already winning based on whatever perception one can construct.

It is not for debaters to echo back to their base, but to encourage others to look for alternative viewpoints. But again, debates may not be the right place for such discourse.

Is your evidence in order?

This point is something that should have fallen under the “win” header, but I am just thinking of it now at the time of writing this section.

I have made comments several times in the past in regards to growing concerned that studies are being misinterpreted by people on Substack and in independent/alternative media sources.

I won’t deny that I have gotten things wrong, and when that occurs I try to correct my mistakes. I am just as fallible as anyone out there, and I always encourage readers to look for additional information to form their own opinions.

With that being said, a serious problem lies in the fact that writers may be prone to presenting information in a manner that drives more readers and paid subscribers, which may cause writers to rely on clickbait and sparse reading of actual material outside of Abstracts and Titles.

Because of this, there’s a lot of information that gets out there that either appear to misinterpret study findings, or may extrapolate more than would be deemed acceptable.

Consider the fact that recently, several people have looked at a study suggesting that more vaccinations (in this case with bivalent vaccines) may lead to more infections.

There are a lot of issues with the study, but as I mentioned in my article many people seemed to have overlooked the fact that prior infection rates may be a better predictor of this discrepancy found rather than actual number of vaccines:

And yet this notion of negative efficacy with each vaccine dose was repeated by several writers sans any discussion of the role of prior infections.

What if, in a debate, this data was presented as an argument against vaccination, only to have the opponent point out that the study was misinterpreted?

The effect here is two-fold: the person who presented this study may be made to seem uninformed on a topic they deem themselves to be knowledgeable on, and if serving as a representative for a group or movement may actually add some credence to those who look for reasons to delegitimize said group or movement.

For COVID vaccine skeptics, the battle over the vaccines is already an uphill battle, and yet when people rely on bad data or misinterpretations, all this does is feed into the talking point that vaccine skeptics are unscientific and only conspiratorially-minded.

Suppose that one makes an argument that more shots are more deleterious. In that regard, wouldn’t a better argument be made over IgG4 subclass conversion rather than negative vaccine efficacy, especially if the latter relies on one misconstruing data in order to make this argument?

A debater’s argument lives and dies based on the evidence presented, and if the evidence isn’t in order it makes room for easy critiques. Why allow for that room, when one can rely on evidence that actually adds to the argument being made, such as the IgG4 argument with respect to additional doses?

As another point, it appears that RFK Jr. refers to remdesivir and the Ebola trial in his book. I haven’t read his book myself yet, so someone can correct me if this is a mistake, but it seems as if RFK Jr. also mentioned the “50% of the people given remdesivir died from remdesivir” in the Ebola trial within his book.

I had issues with the parroting of this talking point, because this talking point generally came from the same people who argued the nuances of dying from COVID and dying with COVID, as well as the issues of not providing early treatment or too low of a dosage of drugs such as ivermectin.

As I mentioned in a prior article, the Ebola trial went counter to what everyone would consider an early treatment trial should do, and especially for a disease as deadly as Ebola:

I don’t know if RFK Jr. brought this up in his Joe Rogan interview, but again, suppose if this point was brought up in a debate only to have this argument be rebutted?

What I find frustrating is that any attempts at encouraging discourse and better reading among vaccine skeptics may be met with hostility, as if it’s improper to encourage people to do more reading and better parsing of information.

I’ve even seen comments made that one should not raise criticisms because this just adds fuel for opponents to use. So do we just let bad ideas fester until a debate, likely to be viewed by millions, results in one side having egg on their face because we are supposed to play “nice” with bad ideas rather than be kind and raise criticisms of said ideas before they get out into the public? Isn’t it better to make sure ideas are substantiated and backed by proper evidence before bold claims are asserted?

One may consider the articles above as “fact-checking”, but we have to keep in mind that the concept of fact-checking has always been around; it’s only recently that it’s gotten a bad rep and misused by people who try to weaponize fact-checking in order to direct public discourse.

Because aren’t peer reviewers and editors fact-checkers by nature? And aren’t those who engage in open dialogue and discourse inherently engaging in fact-checking when we examine evidence?

If we consider that people are willing to debate, we have to consider the evidence they bring up in said debate, and the possibility that if such evidence is lacking then that leaves room for delegitimization and unnecessary critiques.

TL;DR

There’s more that can be said here, but I’ve probably drawn this post out more than I needed to.

In short, the problem is that we are mistaking debates for the much-needed open dialogue and free flow of information. Debates only serve to ossify one’s position, and can backfire when the evidence used is lacking and allow others to make mockery and strawman of one’s supposed position.

And in reality, if one argues that evidence is on their side, then why make the point that one needs to “win” a debate, rather than just presenting the evidence one has in a discussion and having those who see the discourse form their own opinions?

I won’t be surprised of Joe Rogan wants to engage in dialogue rather than a debate, but regardless this need to constantly debate won’t do much if it leaves people uninformed and confused about the actual topics.

We have to consider what it means to debate, whether the intent of a debate relies on the need to “win”, and whether the evidence is sound before one decides to debate.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

As in, I would argue one could make room for a worldview in which a higher power constructed the world in such a way that allowed for evolution to arise

Around this time I actually found myself wanting to read more on evolutionary biology, but strangely my library’s section hardly had any books that weren’t created along the evolution vs creatonism paradigm. I recall finding one book refuting evolution next to one refuting creationism, and yet hardly any books were actually written from a perspective of evolutionary biology. This also occurred with books on global warming, which came from the perspective of rebutting anything that may be deemed a denial of global warming, rather than emphasizing the supposed evidence.

I believe the only book that seemed rather dense in content was one Life Ascending by Nick Lane, as it seemed more focused on the science rather than the reactionary position against creationism.

I think political debate and debates generally need to be evaluated separately. Political debates ostensibly serve the purpose of showcasing differences between candidates and their suitability for public office. Underscoring character issues (with evidence) or inconsistencies (with evidence) has a place in political discourse. Where we have gotten off the track is that evidence is not needed or respected, and debate forums are ideologically infected, subverting open dialogue.

Hmmm, interesting idea of just presenting the evidence and not an actual debate. Of course, that brings up the issue of validity of the evidence. Hotez can present papers that conclude no relation between autism and vaccines and RFKjr. can present papers showing otherwise. Wouldn't they then have to defend their evidence? Perhaps a debate with evidence presented followed by a 10 minute "rebuttal" and that's it. With rules forbidding ad hominem attacks, etc.

I have thought that political campaigns should be based on something similar; just list out 100 possible issues and their general stance on each. And if, after elected, they change their stance, we get to recall them after 3 strikes. Yippeee.