More shots, more infections?

Or maybe prior infections provide a clearer explanation for a new pre-print finding.

I’ve seen a few Substacks posting about this new pre-print1, which supposedly argues that those who are “up-to-date” were more associated with a COVID infection than those who were “not up-to-date”.

The argument over these findings revolve around something that the researchers themselves conclude based upon their results:

Summary Among 48 344 working-aged Cleveland Clinic employees, those “not up-to-date” on COVID-19 vaccination had a lower risk of COVID-19 than those “up-to-date”. The current CDC definition provides a meaningless classification of risk of COVID-19 in the adult population.

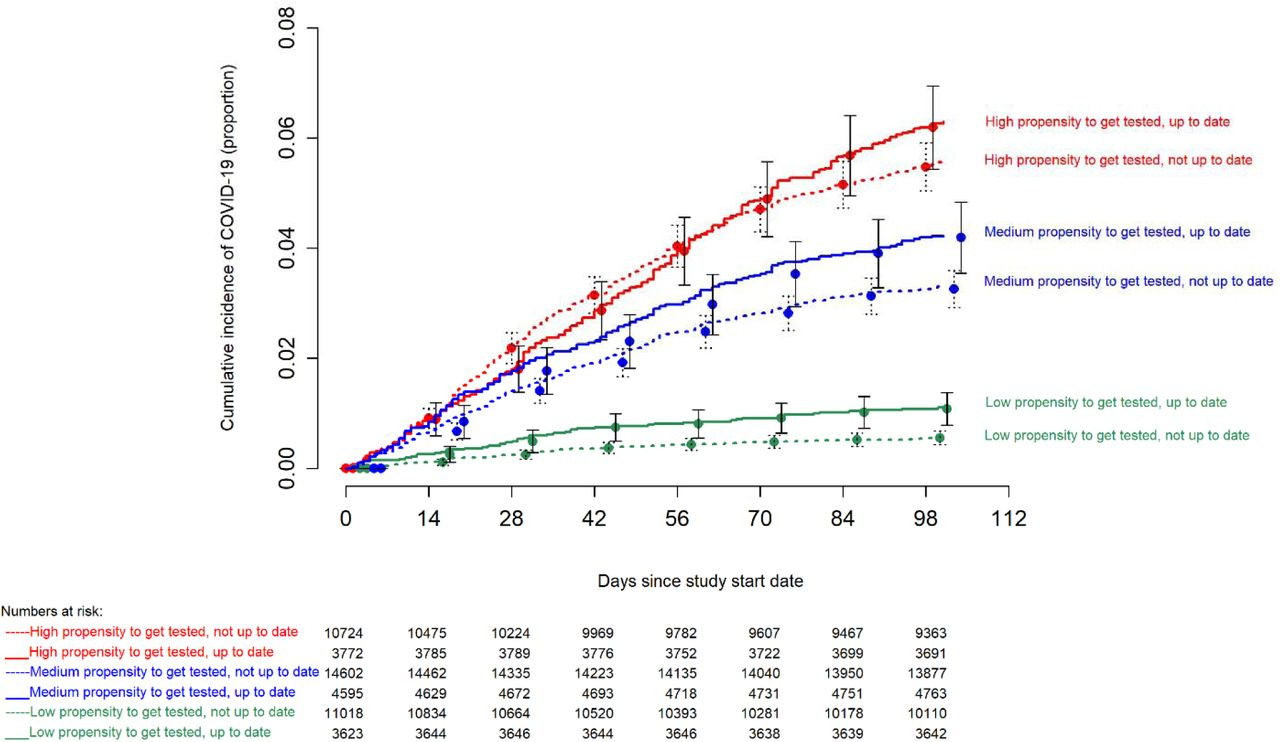

With most people using this Figure as validation of these remarks:

A rather shocking finding, and it would raise some serious questions of efficacy with these vaccines if we assume that the more doses means the greater the risk of COVID infection.

Keep in mind that the intent of this study was to use the newest definition of “up-to-date” provided by the CDC which refers to those who have received the bivalent vaccines.

But this finding would only seem shocking without context.

That is, is this all this study shows?

As a spoiler, I wouldn’t be writing this post if that wasn’t the case.

The study looks at data from Cleveland Clinic employees, starting at the end of January (January 29, 2023) when the XBB lineages became dominant, up until May 10, 2023. Patient information on COVID infection was used to determine infection during the time of the study.

What’s interesting is that testing for COVID was highly varied among Cleveland Clinic employees, such that the range of testing among employees since the pandemic had a range from 0 to 63.5 tests per year. The median appears below one per year, suggesting that about half of the employees were only tested once during the time of COVID:

Altogether, 36 490 subjects (76%) were tested for COVID-19 by a NAAT at least once while employed at Cleveland Clinic. The propensity for COVID-19 testing ranged from 0 to 63.5 per year, with a median of 0.64 and interquartile range spanning 0.32 to 1.27 per year.

This seems to suggest that a “test to stay” type of protocol may not have been in effect. That is, testing may either be voluntary or may occur upon suspected COVID infection.

What this tells us is that the data used to infer COVID infection is likely to be subjective. It’s possible that many people who became sick with COVID may have gone untested or unrecorded unless they voluntarily tested, or were made to test under certain circumstances such as showing symptoms. It may also suggest that people who are more likely to get tested may just be more likely to test positive.

It’s a mix of surveillance as well as false positives that could account for this association (the more you test, the more likely you may turn up positive by way of chance).

And this is made apparent when employee data are stratified by testing propensity2, in which the researchers note that there appears to be an association between those who test more often and cumulative incidences of COVID infection:

On the surface, this finding would appear a bit redundant. Obviously, one would argue that those who get tested more often is likely to test positive- this is a point made clear by people who questioned the degree of COVID testing that was going on in 2020 and 2021. The exact reason for the higher number of testing between employees in this scenario is not made clear, and so multiple reasons can explain why one chooses to get tested more frequently than others.

It is worth noting that if the low propensity group is also comprised of people who never tested, then these results are likely to be biased by an obvious fact in the other direction. Instead of more tests meaning more infections, we also have to deal with the fact that there are those who never tested, and thus would obviously show up negative. Thus, the high propensity group may inherently bias high, and the low propensity group may inherently bias low, and may explain the large discrepancy between these two groups.

Again, the researchers don’t make clear how the propensity groups are stratified.

But here is where I am contentious of some of the remarks I have seen. Rather than default to the “vaccines bad” position, we should hope that people take a bit more time looking into a study and discerning a bit more about what has taken place.

I make this point because it’s quite obvious that the researchers did a bit more testing to stratify data. In this case, the researchers stratified employees based on prior infection history.

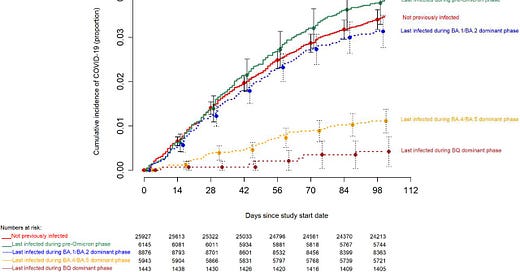

In doing so, the researchers note that this association between infection rates is actually made more apparent when one examines prior infection history, such that those who were infected with a more recent variant were more likely to test negative within the study’s time period (emphasis mine):

In contrast, consideration of prior infection provided a more accurate classification for risk of COVID-19. Those whose last prior SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred during the Omicron BQ or BA.4/BA.5 dominant phases had a substantially and significantly lower risk of COVID-19 than those whose last SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in the early Omicron or pre-Omicron periods or those not previously known to have had COVID-19 (Figure 3).

It’s interesting that the “not previously infected” group appears to show fewer incidences of COVID infection relative to the “pre-Omicron phase” employees, although one has to take into account that seroprevalence data is not provided, so one has to consider that several of these people may have been infected but were not aware of their infection, but were then lumped into the “not previously infected” group.

In further elaboration, the researchers stratify their data based on bivalent vaccination history. Here, they again note that the biggest discrepancy appears to be based on prior infection history, rather than vaccination status (emphasis mine):

When stratified by most recent prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, there was no difference in risk of COVID-19 between the “up-to-date” and “not up-to-date” states within each most recent prior infection group, except for those not previously known to be infected, among whom the “up-to-date” state was associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 than the “not up-to-date” state (Figure 4).

I’ll be honest and say that I’m rather surprised I haven’t seen these Figures referenced in some of the posts that I’ve seen, because I would argue that this isn’t clear evidence of more vaccines leading to more infections.

Rather, it suggests that the immunity one has, and the more matched one’s immunity is to the currently circulating variant, the more likely they are to be protected from infection (spoken of very loosely here).

The researchers provide two explanations for their results, as detailed in the Discussions section. Here, I must highlight a seriously necessary comment, and one that has been continuously overlooked by the CDC and many scientists/doctors:

There are two reasons why not being “up-to-date” on COVID-19 vaccination by the CDC definition was associated with a lower risk of COVID-19. The first is that the bivalent vaccine was somewhat effective against strains that were more similar to the strains on the basis of which the bivalent vaccine was developed, but is not effective against the XBB lineages of the Omicron variant [2]. The second is that the CDC definition does not consider the protective effect of immunity acquired from prior infection. Because the COVID-19 bivalent vaccine provided some protection against the BA.4/BA.5 and BQ lineages [2], those “not-up-to-date” were more likely than those “up-to-date” to have acquired a BA.4/BA.5 or BQ lineage infection when those lineages were the dominant circulating strains. It is now well-known that SARS-CoV-2 infection provides more robust protection than vaccination [4,11,12]. Therefore it is not surprising that not being “up-to-date” according to the CDC definition was associated with a higher risk of prior BA.4/BA.5 or BQ lineage infection, and therefore a lower risk of COVID-19, than being “up-to-date”, while the XBB lineages were dominant.

The researchers here even point to the fact that natural immunity, especially against a variant still in circulation, may provide far better protection that just vaccinating and always being behind the variant curve.

Now, there are important things to remember in the case of this study.

Remember that the argument over natural immunity must take into account the fact that people were infected prior to the start of the study. The same goes for any natural immunity study, but it essentially suggests that enrollment of patients with a recent infection history may inherently lead to lower incidences of infection. This should be taken into account when looking at this information, as distance from last infection, as well as distance from last vaccination, are variables that need to be considered within this context.

Put another way, this may tell us that an earlier enrollment date may see a higher incidence of infection among “not up-to-date” employees, due to the mere fact that they wouldn’t have gotten infected yet prior to the start of the study.

Also, what’s important to consider is something that Brian Mowrey of Unglossed has mentioned several times in his writings on infection and vaccination studies.

That is, one has to take into account the fact that your subjects are likely to be shuffled around to other cohorts during the undertaking of the study.

In this study in particular, employees who received the bivalent booster during the study period appear to have been moved from the “not up-to-date” group to the “up-to-date” group (emphasis mine):

A subject’s vaccination status was “not up-to-date” before receipt of a COVID-19 bivalent vaccine, and “up-to-date” after receipt of the vaccine. Subjects whose employment was terminated during the study period before they had COVID-19 were censored on the date of termination. Curves for the “not up-to-date” state were based on data while the vaccination status was “not up-to-date”. Curves for the “up-to-date” state were based on data from the date the vaccination status changed to “up-to-date”.

So not only is the data from this study heavily dependent upon how many people were infected with the most up-to-date variant, but it is also likely to be influenced by cohort switching during the study. This is likely to influence the results seen.

I normally don’t look at these sorts of studies because it becomes easy to misinterpret the data by omitting certain key parts of the study. The fact that several Substacks have reported on this study, but then failed to point out that the stratification is better justified by prior infection history, rather than vaccination history, is a bit frustrating.

I must emphasize that this doesn’t tell us anything about getting more vaccines being worse for you. Other studies may substantiate this claim, but this study in particular cannot do so, because the researchers themselves found a better explanation for their results when looking at infection history.

And yet, this remark of more vaccines leading to more infection seems to have been reiterated several times over. In a rather cynical sense, I’m curious how many people read the study, or looked to what others wrote in order to form their own opinion. I would argue that one key flaw of Substack is that it causes writers to become far too self-referential. That is, if one person writes about a study, another writer may piggyback off that person’s writing, with the assumption that the previous writer did their due diligence in analyzing the study.

Pair that with a few degrees of separation, and then we’re dealing with misinterpreted data becoming established facts, and unfortunately once it becomes established it becomes harder to argue against these assumptions, especially when they fit a narrative.

But I’ll leave that aside for now.

What’s likely to be the key takeaway from this study is something that many readers should be well-aware of by now. That is, the perspective of immunity that only assesses vaccination status is completely unscientific. It tells us nothing about the nuances of immunity, and why there’s more to immunity that just checking for antibodies, as Joomi Kim has written about several times:

More than anything, this study emphasizes the point that definitions based on vaccination are completely erroneous, and essentially misses the forests for the trees, which the researchers themselves state (emphasis mine):

In conclusion, this study found that not being “up-to-date” on COVID-19 vaccination by the CDC definition was associated with a lower risk of COVID-19 than being “up-to-date”. This study highlights the challenges of counting on protection from a vaccine when the effectiveness of the vaccine decreases over time as new variants emerge that are antigenically very different from those used to develop the vaccine. It also demonstrates the folly of risk classification based solely on receipt of a vaccine of questionable effectiveness while ignoring protection provided by prior infection.

There’s more to immunity than vaccination. Doctors and those in charge of public health should clearly be aware of this fact.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) among Those Up-to-Date and Not Up-to-Date on COVID-19 Vaccination

Nabin K. Shrestha, Patrick C. Burke, Amy S. Nowacki, Steven M. Gordon

medRxiv 2023.06.09.23290893; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.09.23290893

Propensity in this study was defined as the number of PCR tests an employee received divided by how long they were employed at the Cleveland Clinic during the time of COVID.

Where I worked, un-jabbed health professionals with religious exemptions or medical exemptions had to be tested weekly in order to be allowed to remain at work, (until all those PCR tests with expiring EUA got used up and/or that mandate was relaxed). Something similar might partly account for high rate of testing at Cleveland clinic. We swabbed our own noses and brought it to the lab. Half of the time, I had to swab at home and drive the sample to the lab, to keep the weekly schedule. Lots of other employees tested like mad with each respiratory infection to determine if it was COVID. Oddly, I had no symptoms which might have induced any test for respiratory infection from March 2020 to Sept 2022 when I departed, just that string of compulsory PCR weekly tests.

Thanks for pointing out the nuance in the study. I agree most people don’t read the studies and just take either the abstract or the opinion they read here on substack as gospel. I noticed many of the same things you did when I actually read it in full last night. All I could conclude after reading the study was being “up-to-date” provided no measurable benefit.

Maybe if I bothered looking at their adjusted odds ratio in detail I might be convinced that more jabs = more risk of being infected, but they didn’t adjust for the things I was interested in which are pretty much the same things you pointed out in your post. This isn’t a criticism of their methods, the adjustments I would have liked to see may not have been possible depending on the actual data they had available. The study is very transparent in regards to what they found and the limitations of their findings.