News Roundup 7.21.2023

Fraudulence in scientific research; and does bariatric surgery increase the risk of addiction?

Many of my posts go over the email limit and therefore may not make their way to readers. If that’s the case please check out some of the articles this week. Also let me know if this has made it difficult to share articles. Subscribers have stagnated in recent months and I’m curious the degree that article accessibility plays a role.

Research fraudulence never changes

As many of you may have heard by now Stanford University’s president Dr. Marc Tessier-Lavigne has stepped down from this position due to possible ongoing concerns over fraudulent data in some of his published articles.

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne is a neuroscientist, with research stemming from looking at axon growth and regeneration to topics in Alzheimer’s research. Some of these papers were one’s in which Dr. Tessier-Lavigne was considered a primary author1, with a few having him as a co-author.

Some of these accusations can be a bit confusing. There were questions over whether Dr. Tessier-Lavigne actively engaged in misconduct, or whether he was privy to the misconduct of others in his lab. In some instances it appeared that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne did not know of any manipulation of data or images.

Science reports on some of the findings in a hearing (the full report can be found here):

Today, the Stanford board’s special committee released the law firm’s and scientific panels’ findings, which are based on more than 50,000 documents, over 50 interviews, and input from forensic science experts. Its report finds that for seven papers on which Tessier-Lavigne was a middle, or secondary, author, he bears no responsibility for any data manipulation. The primary authors have taken responsibility and in many cases are issuing corrections.

But the 22-page report (plus a cover letter and lengthy appendix on the altered images) found “serious flaws” in all five papers on which Tessier-Lavigne is corresponding or senior author: the 1999 Cell paper, the two 2001 Science papers, a 2004 Nature paper, and the 2009 Nature paper from Genentech. In four of these studies, the investigation found “apparent manipulation of research data by others.” For example, in one case, a single blot from the 2009 Cell paper was used in three different experiments, and a blot from that paper was reused in one of the 2001 Science papers.

The 2004 Nature paper also contains manipulated images, the report found. Although the report says the allegations of fraud and a cover-up at Genentech involving the 2009 Nature paper were “mistaken”—people likely conflated the fraudulent paper a year earlier, and Genentech scientists’ problems replicating the work, it suggests—that paper showed “a lack of rigor” that falls below standards.

The report finds that overall Tessier-Lavigne “did not have actual knowledge of any manipulation of research data” and “was not reckless in failing to identify” the problems in the papers. Yet it concludes that he did not respond adequately when concerns were raised about the papers on PubPeer or by a colleague at four different points over 2 decades—most recently in March 2021. For example, it chides him for failing to follow up when Science did not publish the corrections he submitted.

If blots sound a bit familiar, remember that an article published in Science last year detailed issues in images of Western blots used in Alzheimer’s papers. Blots are a bit notorious for their ability to be easily manipulated, either with lighting alterations or through copy-and-pasting of the same wells.

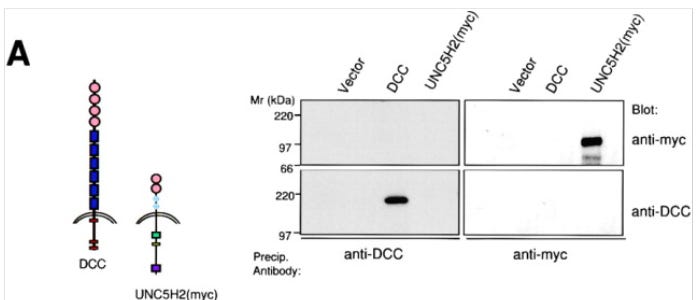

For instance, an article in Stat News shows the following image from the Cell 1999 study2 mentioned that appeared to show signs of copying and pasting (the purple and green boxes are argued to show similar images):

What’s interesting is that the image uploaded to Cell’s online article seems to be rather cleaned up, and so these similarities, whether due to image artifacts or manipulation, don’t appear there:

This could be due to modern techniques allowing for cleaner image qualities, although the extent that one “cleans up” an image is also seriously controversial. This is one of the many examples that have been brought up.

The ensuing fallout has led to some degree of correction for the cited studies, or at least some warnings as is the case for a 2009 Nature3 article that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne was an author on:

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne still seems to be active at Stanford University. However, this fallout points to an issue that has always been there, and yet never really addressed when it comes to science and the rampant degree of fraudulence taking place.

It’s not hard to consider why fraudulence would take place when one considers the incentive structure placed in science, where we only reward people who report positive findings. It also doesn’t help that obscure but illuminating research may not receive the same degree of funding as things that the public may be aware of. An obscure disease that affects very few individuals will not receive the same level of funding as HIV or cancer research.

All of this speaks more to the fact that fraudulent science is always happening, but no one seems to speak up or to do anything meaningful about it.

Consider the number of COVID studies that have come out in recent years. I wouldn’t be surprised if we come to find out that hundreds or thousands of these studies had serious issues with data manipulation or poor methodologies. We’re sort of noticing this in real time already.

Which adds more reason for why we need more critical readers of science. Due diligence is needed to point out flaws in studies or to recognize that some studies are just bad studies. If we start from the premise that all studies have issues then it allows us to be able to discern what these issues are so that we get a better understanding for how to interpret such studies.

We’re likely to never see the end of bad science getting through, but that’s all the more reason why we should be more proactive in discerning what we read and come across.

Also, for anyone interested here are some additional links to the two 2001 Science articles. It’s surprising how many outlets have mentioned these studies and yet haven’t provided any links to them:

Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex4

Binding of DCC by netrin-1 to mediate axon guidance independent of adenosine A2B receptor activation5

Is addiction all in the gut?

A recent news article caught my eye for its rather perplexing claim:

It doesn’t seem like an intrinsic association at first. I mean, how could weight-loss surgery increase one’s risk of addiction?

The study was published online6 just today, and I have yet to fully read the study. However, that isn’t necessarily the point of referencing this study, but rather seeing this study got me thinking about the role of our gut in shaping our overall health.

A few searches online seem to make references towards the association between bariatric surgery and addiction, so it’s not as if this research doesn’t have some basis in the literature already.

Now, the first assumption that one may have is to consider that bariatric surgery may make addictive substances more available and readily absorbed. It’s been argued that the pharmacokinetics of alcohol changes after surgery, making some people more susceptible to quickly becoming drunk. Weight loss may also be a factor wherein lower weights may lead to a lower dosage threshold for substances.

All of these are possible factors. However, in this era of GLP-1 receptor agonists we may have another explanation.

A while back I came across some remarks that bariatric surgery can aid in weight loss not by the physical/mechanical limitations brought on by the surgery, but possibly due to the fact that the surgery almost causes a “reboot” in the proteins produced by the body (timestamped below- the video below is a discussion on another diabetes/weight-loss drug that was being researched):

Note that incretin hormones such as GLP-1 are produced by cells in the intestines, which then go to the pancreas where they activate pancreatic cells to produce insulin. However, GLP-1 that enters the brain may bind to various GLP-1 receptors and induce a feeling of fullness. It appears that this pathway may also be associated with addiction as well, which has been validated by the widespread use of GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic and their associations with reductions in the need for alcohol and other substances aside from food.

So what does all of this mean?

It may suggest that signaling within the gut is something that is likely to be altered by way of bariatric surgery, which may help with weight loss or have an unfortunate consequence of increasing addictive behaviors. On one hand, some evidence suggests that bariatric surgery is associated with increases in GLP-1 production and may explain appetite and addiction suppression in much the same ways that Ozempic can.7 However, there’s also a possibility that cellular signaling pathways may be detrimentally altered, in which case the end result may be reduced incretin expression in the long-run, or even cellular dysfunction. The latter idea is one that has barely been explored, but it’s not too much of a thought to consider that there could be lasting changes to the gut.

Overall, this tells us that there’s likely to be a tighter association between the gut-brain axis as it relates to addiction than we currently know of. We may come to find that the gut plays a more significant role in addiction that we give it credit for.

It also tells us that there’s more things to consider when it comes to procedures and surgical interventions than just anatomical changes. It’s likely that these procedures may alter how our cells communicate with one another. Consider that there’s been growing fascinating with how Botox and the blunting of facial nerves may actually alter mood, likely due to interruptions in the face-brain axis (is this a thing?).

All of this is food for thought, but it raises some things to consider in how there’s a greater connection between systems within our bodies than we make out. We may come to find that there’s deeper connections that influence our overall health.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

For most publications the organization of authors is based on seniority or some sort of hierarchy. That is, the PI tends to be first author on papers, with other co-authors coming next, then graduate students, then lab techs, and then maybe a few glassware cleaners being last.

Hong, K., Hinck, L., Nishiyama, M., Poo, M. M., Tessier-Lavigne, M., & Stein, E. (1999). A ligand-gated association between cytoplasmic domains of UNC5 and DCC family receptors converts netrin-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion. Cell, 97(7), 927–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80804-1

Nikolaev, A., McLaughlin, T., O’Leary, D. et al. APP binds DR6 to trigger axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases. Nature 457, 981–989 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07767

Stein, E., & Tessier-Lavigne, M. (2001). Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex. Science (New York, N.Y.), 291(5510), 1928–1938. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1058445

Stein, E., Zou, Y., Poo , M., & Tessier-Lavigne, M. (2001). Binding of DCC by netrin-1 to mediate axon guidance independent of adenosine A2B receptor activation. Science (New York, N.Y.), 291(5510), 1976–1982. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059391

Svensson, P-A, Peltonen, M, Andersson-Assarsson, JC, et al. Non-alcohol substance use disorder after bariatric surgery in the prospective, controlled Swedish Obese Subjects study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023; 31( 8): 2171- 2177. doi:10.1002/oby.23800

Hutch, C. R., & Sandoval, D. (2017). The Role of GLP-1 in the Metabolic Success of Bariatric Surgery. Endocrinology, 158(12), 4139–4151. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2017-00564

I wouldn't expect articles that exceed email length to have too much affect on subscriptions, but who knows. I tend to start reading in email, if the article is formatted in a readable way, and then go to the Web to like and read comments, no matter what the source. If it's too long for email, I go to the Web that much sooner.

Your email formatting is fine. I don't know for sure what's up with the others that come through as hard-formatted with ridiculously long lines that don't wrap. It could be Outlook or Proton Mail Bridge or ... something. It's not worth the trouble to hunt down. But probably Outlook.

I feel like things are slowing down generally in these parts of Substack. I see it in the posting frequency among my paid subscriptions. I also see it in my own blog's stats, but that seems to have more to do with how much commenting I do elsewhere.