Herpes reactivation following COVID Vaccination

A look at the limited number of case reports and literature reviews.

Prior posts for those interested:

In lieu of the prior posts we can consider the effect of COVID vaccination on the uptick in HHV reactivation. As many of us are aware, it was rather common to see people report evidence of herpes zoster (shingles) following vaccination, and led to great attention over what this may mean.

Not much seems to have come from these initial reports, and so it’s quite possible that a lot of information has been taken for granted that would otherwise provide pertinent and relevant information for all of the adverse events seen, especially in assessing overlaps between Long COVID post-infection as well as “long vaccination”.

For instance, most reports on HHV reactivation have focused predominately on chickenpox/shingles, and so other HHVs have not been as well-examined. There’s also the fact that many of these reports were considered mild and transient, which may not bode well given the fact that many HHVs have been associated with cardiovascular issues such as myocarditis.

With all of this in mind we’ll take a look at a few case reports and literature reviews of HHV reactivation following COVID vaccination. Note that some of these case reports and studies will likely be included in various systematic and literature reviews. Also, once again, the focus here will unfortunately be more directed towards herpes zoster (shingles) and varicella zoster virus (chickenpox).

Things to consider- PR and PR-LE

Many of the HHVs present with cutaneous (skin) symptoms such as rashes, itchiness, and other sorts of symptoms. Most HHVs, such as HSV-1 and 2 and VZV present with blister-like rashes.

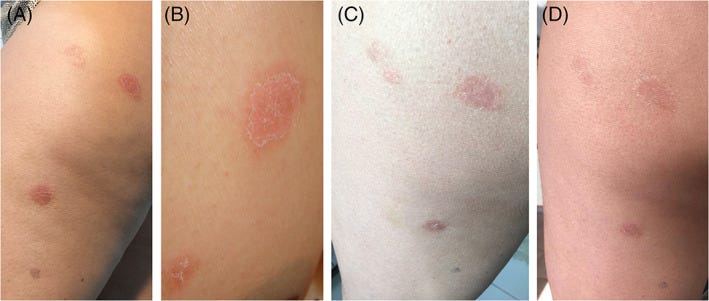

HHV-6 and HHV-7 can also present with cutaneous symptoms during reactivation, although in the case of these HHVs the skin rashes are a bit unique, with the presentation being labeled as pityriasis rosea1 (“scaly pink”). The rashes are more oval and larger in appearance, usually involving the trunk (torso) of the body. The rash can initially start as a small oval patch called a herald patch on the face or trunk of the body, although some instances of PR may not initially present with said patch.

Prior to the presentation of the herald patch symptoms of a sore throat, headache, fatigue, or fever may precede days before herald patch formation. Afterwards, the rash may extend the rest of a person’s trunk in a Christmas tree-like fashion, and so these cutaneous presentations have also been called a “Christmas tree rash”. Usually these rashes present for several weeks, and are usually considered non-severe in most cases and tend to fully resolve.

Although it’s been suggested that several cases of PR are related to HHV-6 and HHV-7 reactivation, the actual etiology can sometimes not be known due to limited investigations. For instance, PR may occur in response to certain drugs or vaccinations rather than due to HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation.

In these cases of drug/vaccine-related PR, the skin rashes are termed pityriasis rosea-like eruptions (PR-LE). The cause for PR-LE is generally unknown, although it’s been proposed that the body’s hyperactivated response to a drug or vaccine may elicit the cutaneous symptoms.

It’s been suggested that PR and PR-LE rates increased since the onset of the pandemic, providing further association between HHV activation and SARS-COV2 (for both the virus and the vaccine).

Unlike PR, the rashes that present as PR-LE are itchy and appear darker/redder. Skin biopsies also tend to present with evidence of eosinophil infiltration.

Drago, et al.2 provides an outline distinguishing between PR and PR-LE.

One of the issues with differentiating between PR and PR-LE is due to the fact that many clinical assessments may not tests for the presence of HHV-6/HHV-7. Skin biopsies may not be taken from patients as well to confirm the presence of HHV or eosinophils.

One clear method of discerning between PR and PR-LE is the discontinuation of certain drugs to see if a patient’s skin clears of the itchy rashes, although this wouldn’t be possible in the case of vaccinations (you can’t “de-vaccinate” someone). Therefore, there tends not be clear evidence of HHV reactivation in some instances of PR or PR-LE events due to the lack of testing, with PR and PR-LE providing proximal associations that a viral reactivation is occurring.

There’s also the fact that PR and PR-LE may be mistaken for other skin conditions such as psoriasis, chickenpox/shingles, eczema, or others, and so clinicians may incorrectly conflate presentations of one HHV with either another HHV or some other etiological agent. Therefore, it’s quite possible that some reports of PR may be underreported due to mistaking them for other conditions.

All this to say that there’s likely to be some issues in data collection when it comes HHV reactivation following COVID vaccination. It’s possible that PR and PR-LE may have been overlooked or assumed to have been related to VZV and the presentation of shingles.

HHV Reactivation- Select Studies

Similar to the prior posts there’s a lot of case reports and studies to cover, so there may be a bit of disorganization going on. Also, remember that the literature is biased towards VZV reports.

Shafiee, et al.

This is one of the most recent systematic reviews on HHV reactivation, and in fact these posts on HHV were owed in part to this systematic review publication. After screening different studies the authors came across 80 studies worth reviewing (11 observational cohorts, 59 case reports , and 10 case report series).

Overall, evidence suggested an association between COVID vaccinations and VZV reactivation, with most of these episodes of reactivation being associated with the mRNA vaccines in particular. However, keep in mind that observational studies were likely designed with VZV assessments in mind, and so other HHVs may not have been examined. Interestingly, case reports/case series note a higher degree of HHV reactivation after the 1st dose relative to the 2nd or the booster.

Note that the case reports show an age-stratified presentation where VZV and CMV appeared in older patients (mean age ~55 and 60, respectively) whereas EBV, HSV, and HHV-6 reactivation appeared to occur in younger cohorts, although limited case reports may bias these results.

Most of the reports from this review were from 2022. Also, HHV-6 reactivation was at a scant 2 relative to the VZV reactivation which made up 70% of the case reports, which may either suggest that the prevalence of HHV-6 reactivation may be far fewer than other HHVs, or clinicians may not be aware of the need to assess for HHV-6/HHV-7. The lack of observational studies for other HHVs may suggest that researchers may have improperly focused on VZV, biasing the available information and creating a false impression of what HHVs to look out for.

Navarro-Bielsa, et al.

In contrast to Shafiee, et al. a review from Navarro-Bielsa, et al. examined reports provided to the European database of suspected adverse drug reactions (EudraVigilance), which seem to note a rather interesting collection of reports, specifically with respect to the extremely high case of HHV-6 following Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine:

Remember that VAERS and similar reporting systems may not differentiate between coincidental infections or infections related to vaccination. Therefore, it’s possible that many of these reports are tangential infections. The chart also doesn’t differentiate based upon other demographic data, including dosage. It’s possible that the high level of HHV-6 reports may be due to the approval period for Pfizer/BionNTech’s vaccine for children, such that most children may have been given Pfizer/BioNTech relative to other COVID vaccines, and so the timing may have been associated with childhood infection with HHV-6.

Now, that being said, if childhood infection were the explanation for the high HHV-6 infections we should at least expect a similar pattern to show up across all the other viruses if that were the case. The same can be said for the other vaccines, but again a smaller sample size of the other vaccines should be taken into account. Also, cutaneous presentation of VZV via chickenpox and roseola infantum via HHV-6 may suggest a difference in recognition of viral infection relative to EBV or CMV, which may be mistaken for common respiratory infections if they don’t present with cutaneous symptoms. One does have to consider the fact that the VZV and HHV-6 numbers are the same (not similar), and so VAERS-like reporting may have categorized these two together. VAERS-like reports are subjective to some degree, and so unless a full examination is conducted it’s hard to ascertain what these values mean.

The authors don’t provide an explanation for these figures, although the article is an interesting read for those who would like additional context for HHV reactivation.

Hertel, et al.

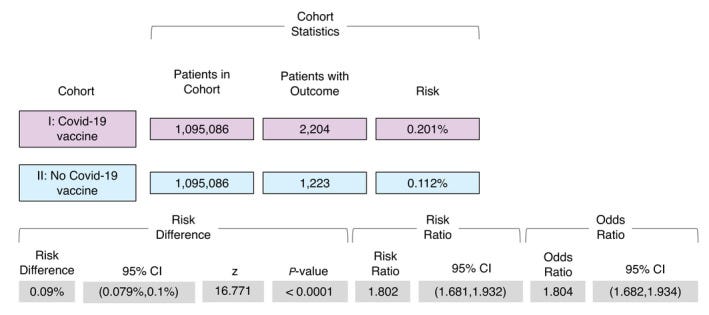

This review looked at over 1 million records within TriNetX’s global database for evidence of VZV reactivation following COVID vaccination. In this case, records were separated into two cohorts based upon vaccination records (Cohort I- vaccinated; Cohort II- unvaccinated). Patients were matched to remove confounders and were examined for rates of VZV reactivation between the two cohorts. Unfortunately, this study, like many others, focused solely on VZV reactivation.

The cohorts leaned older (mean age ~54) which would be expected. Patients within Cohort 1 were also predominately vaccinated with Pfizer/Moderna (~88%). Moderna vaccination was slightly below 10% and AstraZeneca around 1.5%. VZV reactivation was measured based upon reported cases within a 60-day time period following COVID vaccination. Information from the TriNetX database goes up until November 2021, so keep in mind that 2022 and 2023 are not accounted for in this data.

Given these parameters, there appeared to be evidently higher VZV reactivation among the COVID-vaccinated cohort relative to the unvaccinated cohort:

Unfortunately, the researchers don’t make mention of the prevalence of VZV reactivation with respect to vaccine dosage. They also don’t stratify the events relative to the vaccines as well. Also, the use of a 60-day window is rather broad and doesn’t provide insights into VZV reactivation relative to the vaccination period (i.e. are most of the reported VZV reactivations occurring days after vaccination or weeks/months afterwards?).

So overall, this study confirms the anecdotal/observational accounts of shingles and other markers for VZV reactivation, although it doesn’t add much additional context given the limitations of the study.

Pityriasis Rosea Post-Vaccination

Given that most investigations into HHV reactivation have focused on VZV in particular, I thought it pertinent to look for evidence of PR or PR-LE post-COVID vaccination and see what the literature mentions. Note that in many cases of PR or PR-LE a confirmation of HHV-6 or HHV-7 reactivation may not be made, and so it’s possible that the two (PR and PR-LE) may be used interchangeably.

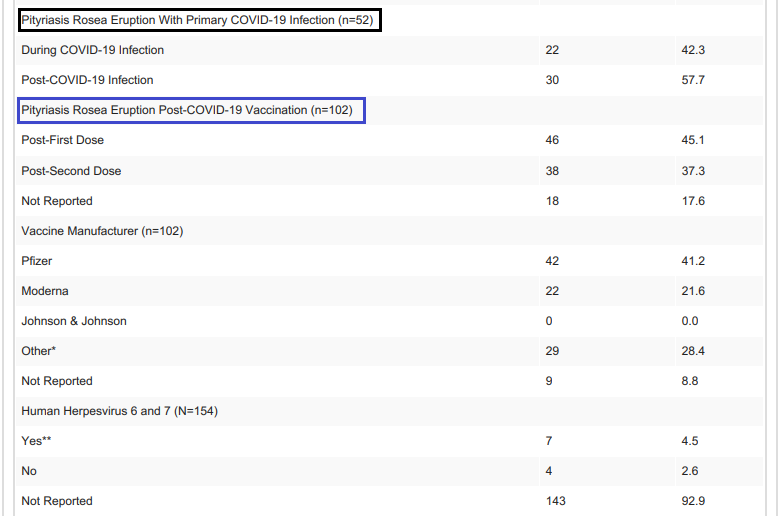

Wong, et al.

This review from Wong, et al. examined case reports of PR following COVID infection and COVID vaccination. Unfortunately, as is expected, there doesn’t appear to be a distinction between PR and PR-LE based upon the case reports examined. Also, confirmation of HHV-6 and HHV-7 did not occur in most of these cases, leaving the cause of these cutaneous symptoms relatively unknown.

It’s worth noting that higher rates of PR/PR-LE occurred after the first dose of a COVID vaccine, with many of the reported cases occurring in those given Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine. Again, keep in mind a possible bias towards Pfizer/BioNTech and PR/PR-LE due to vaccination rates between the different vaccines.

In one review7 of cutaneous reactions in Turkish patients following COVID vaccination there appeared to be evidence of PR/PR-LE following the inactivated virus vaccine CoronaVac. Although the authors argue a higher rate of more severe cutaneous reactions following Pfizer/BioNTech, the evidence of PR/PR-LE with other vaccines suggest a possible overlap in causative agent.

Keep in mind that PR/PR-LE have been recognized following other types of vaccinations, and so all of these episodes may be tied to immunological responses to vaccination.

With that being said we’ll take a small look at case reports, although investigations may be rather limiting and may not provide much additional details. Because of this the scope of case reports will be limited.

For instance, one case report from Wang, et al.8 notes a 40-year old man who developed an extremely itchy skin rash 7 days after receiving the first dose of Moderna’s COVID vaccine. The rashes persisted the following days, becoming more oval in nature. No herald patch was recognized, although histopathological assessments of the rashes noted eosinophil infiltrates. The patient was noted to have had urticaria (hives) months prior.

The patient did not want further clinical assessments so no testing for viral agents was conducted, although the itchiness of the rashes along with the eosinophil infiltrate may be more suggestive of PR-LE rather than PR due to HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation. Note that the eosinophil infiltrate that Wang, et al. identified was argued to be different than what has been recorded in the literature, and so this may not be a clear case of PR-LE.

Wang, et al. also include information for other case reports, although the diagnosis and treatment for PR/PR-LE is not provided in many of these case reports, again suggesting a lack of investigation for many of these case reports.

One early case report from Cohen, et al.9 notes of a 66-year old man who began developing a rash a week after his first dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Histopathological findings suggested PR, although no viral examination was conducted, and the patient seemed to have been prescribed triamcinolone for his itchiness.

A case report from Bin Rubaian, et al.10 notes of a 15-year old female who developed rashes 2 days following her second Pfizer/BioNTech dose. The rash would later spread throughout her body, leaving her self-conscious of the rashes.

A herald patch was noted, and the patient was diagnosed with PR and was prescribed Acyclovir (antiviral) for one week. The rashes stopped appearing following the Acyclovir treatment. Although no viral confirmation was conducted, the use of the antiviral Acyclovir and the reduction in rash formation may be suggestive of HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation.

One atypical case report from Pedrazini, M. C., & da Silva, M. H.11 notes of a 53-year old woman who received two doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine and eventual presented with a unique case of rashes.

The patient was described has having autoimmune disease via Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis prior to vaccination. Nearly two weeks after the second dose of the COVID vaccine she developed rashes on her right thigh which were mildly itchy. she attempted to treat the rash with an antifungal cream.

After 8 days the lesion grew along with other lesions located on the patient’s calf, buttocks, and thigh. A dermatologist, along with an infectious disease specialist, would later diagnose the patient with PR, and prescribed her antiseptic medications along with L-Lysine supplementation.

In this case, the typical rashes seen with PR/PR-LE were not present, with the cutaneous presentation involving various lesions relegated to the lower extremities of the body instead of the typical presentation on the torso of patients.

Although atypical in nature, the authors don’t provide any information on histopathological results, and so it’s curious what measures were used to come to the diagnosis of PR. Personally, I also couldn’t discern the supposed herald patch that is pointed out in Figure 1 so I’m a bit hesitant with this diagnosis.

That being said, it’s worth considering that PR/PR-LE may not always present in a similar fashion as what’s reported in the literature. This case also again emphasizes the fact that PR/PR-LE may occur with different vaccines.

For this atypical presentation the authors make the following remarks:

Diagnosis of typical PR, with Christmas tree‐shaped truncal involvement, is not difficult for doctors like dermatologists or general pediatrician however, its atypical presentations can be challenging even for these professionals. 13 In the typical form diagnostic doubts hardly arise but, as 20% of the cases present atypically, this can favor unnecessary procedures and drug prescriptions. 34 Although it usually demonstrates a truncal predilection, this presentation may be absent in some patients who instead exhibit atypical features and distributions such as only lesions located in the extremities, 12 as seen in this case report. The fact that PR is also confused with other pathologies such as psoriasis, syphilis, allergic dermatoses and fungi 35 would justify the use of cream with ketoconazole and associations by the patient when the herald patch appeared.

Regarding the fact that the “mother patch” appeared soon after one of the doses of Oxford‐AstraZeneca, there are other reports described of PR after other vaccine schedules, for example, against smallpox, tuberculosis, influenza, papillomavirus, poliomyelitis, tetanus, pneumococcus, triple viral (diphtheria‐pertussis‐tetanus), hepatitis B and yellow fever. 11 A report issued by the UK in June 2021 reports 52 cases of PR after Oxford‐AstraZeneca vaccination in the first half of the year but does not give details of whether the reactions were after the first or second dose of the vaccine. 10 Other anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines also had PR as an adverse reaction 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 with the manifestation occurring after the first dose, 28 or after the second dose 28 , 30 , 31 and in some patients, the medallion (herald patch) and some lesions, occur after the first dose with exacerbation after the second dose. 29 , 31

Overall, these case reports note of a phenomenon that has been well-recognized based upon anecdotal evidence. That is, it’s been rather evident that shingles and other cutaneous symptoms have developed in some people post-COVID vaccination.

The question remains to what degree many of these presentations are owed to HHV reactivation, or whether some of the symptoms, as in the case of PR-LE, are due to other factors such as an immunological response to the vaccines that manifest as lesions or rashes.

And even as many pieces of literature come out recognizing this association between COVID vaccination and possible HHV reactivation there still appears to be a lack of investigations that provide deeper insights. Consider that most reports on PR/PR-LE don’t make mention of HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation, which would be a critical diagnosis to uncover as it would suggest a broader phenomenon of HHV reactivation.

So the degree of HHV reactivation is still relatively unknow. More importantly, cutaneous symptoms are not the only indication that HHV reactivation may be occurring. As noted in the case report from Bookhout, et al.12 from the first report some episodes of HHV reactivation may not be associated with cutaneous presentations, and therefore may go unrecognized until a possible fata incident may occur, such as may be the case for meningitis caused by HHV reactivation.

This will be covered within the next post, along with some attempts at consilience and rationalization of the evidence shown.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Litchman G, Nair PA, Le JK. Pityriasis Rosea. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448091/

Drago, F., Ciccarese, G., & Parodi, A. (2018). Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: How to distinguish them?. JAAD case reports, 4(8), 800–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

Shafiee, A., Amini, M. J., Arabzadeh Bahri, R., Jafarabady, K., Salehi, S. A., Hajishah, H., & Mozhgani, S. H. (2023). Herpesviruses reactivation following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of medical research, 28(1), 278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01238-9

Navarro-Bielsa, A., Gracia-Cazaña, T., Aldea-Manrique, B., Abadías-Granado, I., Ballano, A., Bernad, I., & Gilaberte, Y. (2023). COVID-19 infection and vaccines: potential triggers of Herpesviridae reactivation. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia, 98(3), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2022.09.004

Hertel, M., Heiland, M., Nahles, S., von Laffert, M., Mura, C., Bourne, P. E., Preissner, R., & Preissner, S. (2022). Real-world evidence from over one million COVID-19 vaccinations is consistent with reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 36(8), 1342–1348. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18184

Wong, N., Cascardo, C. A., Mansour, M., Qian, V., & Potts, G. A. (2023). A Review of Pityriasis Rosea in Relation to SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination. Cureus, 15(5), e38772. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38772

Cebeci Kahraman, F., Savaş Erdoğan, S., Aktaş, N. D., Albayrak, H., Türkmen, D., Borlu, M., Arıca, D. A., Demirbaş, A., Akbayrak, A., Polat Ekinci, A., Gökçek, G. E., Çelik, H. A., Taşolar, M. K., An, İ., Temiz, S. A., Hazinedar, E., Ayhan, E., Hızlı, P., Solak, E. Ö., Kılıç, A., … Yılmaz, E. (2022). Cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination in Turkey: A multicenter study. Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 21(9), 3692–3703. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.15209

Wang, C. S., Chen, H. H., & Liu, S. H. (2022). Pityriasis Rosea-like eruptions following COVID-19 mRNA-1273 vaccination: A case report and literature review. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi, 121(5), 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.12.028

Cohen, O. G., Clark, A. K., Milbar, H., & Tarlow, M. (2021). Pityriasis rosea after administration of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 17(11), 4097–4098. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1963173

Bin Rubaian, N. F., Almuhaidib, S. R., Aljarri, S. A., & Alamri, A. S. (2022). Pityriasis Rosea Following Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccination in an Adolescent Girl. Cureus, 14(7), e27108. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27108

Pedrazini, M. C., & da Silva, M. H. (2021). Pityriasis rosea-like cutaneous eruption as a possible dermatological manifestation after Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine: Case report and brief literature review. Dermatologic therapy, 34(6), e15129. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15129

Bookhout, C., Moylan, V., & Thorne, L. B. (2016). Two fatal herpesvirus cases: Treatable but easily missed diagnoses. IDCases, 6, 65–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2016.09.013

I have a neighbor who is in his 50's who just came down with shingles. I know an older woman who also came down with shingles. It seems to be very common now.

What we haven't heard is a lack of outbreaks with these types of infections. And with the MSM, we'd hear about them if they were not occurring. But, crickets.