FDA releases final guidance on NAC products

What this possibly means for NAC dietary supplements moving forward.

Last week the FDA issued a final guidance on N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and their enforcement discretion in regards to the sale and distribution of products containing NAC.

Although the agency issued a notice of a guidance in the Spring, it was only last week that the FDA published a final draft of the guidance in a 5 page (really 3 page) document considered a “guidance for industry”.

This comes after months of ongoing battles between the FDA and supplement manufacturers after the FDA suddenly began issuing warnings about NAC, culminating into many retailers including Amazon and Walmart pulling NAC supplements off of their shelves.

NAC has been widely available for decades, and so the sudden warnings obviously raised concerns about whether this has any association with the current pandemic and at-home treatment options.

At the center of this debate was the argument over whether NAC qualified as a “dietary supplement”.

Dietary supplements are defined by the FDA’s Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) as follows (taken from the final guidance):

The term “dietary supplement” is defined by the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 321(ff)(3)(B)) to exclude:

(i) an article that is approved as a new drug under section 505 [of the FD&C Act], certified as an antibiotic under section 507 [of the FD&C Act], or licensed as a biologic under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 262), or

(ii) an article authorized for investigation as a new drug, antibiotic, or biological for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted and for which the existence of such investigations has been made public,

which was not before such approval, certification, licensing, or authorization marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food unless the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article would be lawful under [the FD&C] Act.

Thus, if an article has been approved as a new drug under section 505 of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 355), products containing that article are outside the definition of a dietary supplement unless either of two exceptions applies. First, there is an exception if the article was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food before such approval. Second, there is an exception if FDA (under authority delegated by the Secretary of Health and Human Services) issues a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article would be lawful under the FD&C Act.

Where NAC runs afoul appears to be due to a slight technicality, in that NAC was approved as a drug before it was marketed as a supplement. Because of this technicality, NAC falls under the category of a drug rather than a supplement, meaning that it undergoes different regulatory procedures and rules for marketing:

FDA has determined that NAC is excluded from the dietary supplement definition under section 201(ff)(3)(B)(i) of the FD&C Act because NAC was approved as a new drug before it was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food. Specifically, NAC (i.e., acetylcysteine) was approved as a new drug under section 505 of the FD&C Act on September 14, 1963 (see 28 FR 13509 (Dec. 13, 1963) (announcing the approval)). FDA is not aware of any evidence that NAC was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food prior to September 14, 1963.

This makes the current situation even more baffling. After decades of being widely available in most retail stores, why the sudden crackdown?

NAC has been studied rather extensively over the past few decades, and many clinical trials have gone underway to look at some of the therapeutic effects from NAC use, including as a prophylactic/treatment for COVID.

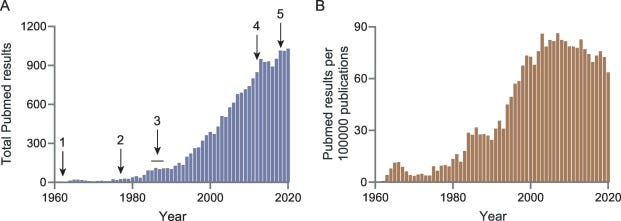

For example, Pedre, et. al.1 provides two graphs showing the number of NAC publications found on Pubmed over the past few years:

The popularity of NAC has continuously increased over the last 60 years. Since 2009, the yearly number of NAC-related publications has been well above 900, and since 2013 the number has plateaued at around 1000 papers per year (Fig. 1A). Even if the increasing number of NAC-related publications is to be normalized against the overall increase in PubMed publications, it is still apparent that interest in NAC has remained at a high level over the last 20 years (Fig. 1B).

It could be for this reason that many speculate the FDA is targeting NAC, possibly due to the ability for new drugs to come to market under patent that would be undermined by the widespread availability of NAC.

Personally, I don’t agree much with this take because NAC is such a small molecule, comprised only of an amino acid with an acetyl group2 attached. It’d be rather difficult to patent such a molecule on its own, although many investigative drugs have combined NAC with other agents to examine their effects in clinical trials.

It could be that medications that elevate l-cysteine levels may be patented, which may make it difficult to market such a drug when supplementation with NAC directly may end up causing the same effect.

Instead, I’m more of the belief that this is just another crackdown of at-home, alternative methods of treatment especially in the fight against COVID. It’s a way for bureaucratic agencies to flex their authority by targeting supplements and limiting options for the layperson. It just so happens that NAC, due to the technicality in definitions indicated above, is able to be targeted unlike other agents such as Quercetin or Vitamin D.

As of now, there are questions as to what discretion may be used. It appears that the FDA may allow for dietary supplements containing NAC as long as it meets certain criteria:

Accordingly, as described below, we intend to exercise enforcement discretion with respect to the sale and distribution of certain products that contain NAC and are labeled as dietary supplements. The enforcement discretion policy applies to products that would be lawfully marketed dietary supplements if NAC were not excluded from the definition of “dietary supplement” and that are not otherwise in violation of the FD&C Act. For example, with respect to the sale of an NAC-containing product that is labeled as a dietary supplement, FDA does not intend to object solely because the product is intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man and, therefore, is a drug under section 201(g)(1)(C) of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 321(g)(1)(C)).4 However, this enforcement discretion policy does not apply to an NACcontaining product that is labeled as a dietary supplement but is intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease and, therefore, is a drug under section 201(g)(1)(B) of the FD&C Act. Likewise, for example, the enforcement discretion policy does not apply to NAC-containing products that are adulterated or misbranded under the FD&C Act (other than those misbranded only because they contain NAC and are labeled as dietary supplements).

A lot of this is too much legalese for me, but I take this to mean that NAC supplements may be marketed as dietary supplements even if it has mechanisms that would cause it to act as a drug, so long as the label and marketing of said supplements don’t include indications of these drug actions.

Put another way, NAC may be marketed for “immune support” even though it has other therapeutic effects, but it can’t explicitly state that NAC can treat hangovers, COVID, or acetaminophen overdoses-essentially any wording that would indicate that it can be used as a drug, unlike over-the-counter pain relievers that state they can be used against headaches or muscle aches explicitly.

That may explain why I came across NAC while at a trip to Walmart, since I thought most big retailers hurried to remove these from the shelves:

Currently, the future for NAC is not clear. In March 31, 2022 the FDA responded to two citizen petitions from the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN) and Natural Products Association (NPA) in regards to the removal of NAC from stores due to its historical use as a supplement, arguing that NAC should not be excluded from the category of dietary supplement. The FDA ruled that NAC does not fall under the category of dietary supplement due to the law provided above (FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 321(ff)(3)(B)), and instead falls under the category of a drug.

However, the FDA is allowing for part of the NPA’s petition in regards to rulemaking on NAC as a dietary supplement. In the meantime, the FDA is reviewing the safety profile of NAC, and it’s likely that this review may determine the future availability of NAC:

Unless we identify safety-related concerns during our ongoing review, FDA intends to exercise enforcement discretion until either of the following occurs: we complete notice-and-comment rulemaking to allow the use of NAC in or as a dietary supplement (should we move forward with such proceedings) or we deny the NPA citizen petition’s request for rulemaking. Should we determine that this enforcement discretion policy is no longer appropriate, we will withdraw or revise this guidance in accordance with 21 CFR 10.115.

And this may be the area to keep a watchful eye out. Should a supplement that has been extensively used and widely available suddenly come up with concerning safety issues that would pull it from market, we may argue that something may be afoot.

Remember that the CDC came out with concerns over melatonin recently, which appeared to be more fear mongering rather than legitimate concerns over widespread melatonin overdosing:

Within the coming months we may find out how the FDA will rule on the matter, but for now I will state that I may (or may not) have bought some NAC to try out.

Remember, consult your doctor and don’t take the information here as medical advice!

Also, I would normally like to add additional information in regards to mechanisms of action for specific compounds or drugs that I highlight, however several of my recent posts have been rather long so I will keep that for next post to keep this one shorter. So please look out for that post.

For those who would like to read a bit more on this ruling I came across these two articles that you may find interesting, as they include comments from the groups who issued the citizen’s petition.

Natural Products Insider: FDA issues final ‘enforcement discretion’ guidance on NAC

Whole Foods Magazine (yes, this is actually a thing): FDA Issues Final Guidance on “Enforcement Discretion” of NAC

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Pedre, B., Barayeu, U., Ezeriņa, D., & Dick, T. P. (2021). The mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine (NAC): The emerging role of H2S and sulfane sulfur species. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 228, 107916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107916

An acetyl group is a functional group that has a carbonyl (carbon double-bonded to oxygen) group that’s attached to a methyl (-CH3) group. When this acetyl is bonded to a nitrogen (N) the entire group gets labeled as an N-acetyl group, hence the name N-acetyl cysteine since the acetyl group is attached to the amine (nitrogen) of L-cysteine.

Attack on ivermectin.

Attack on hydroxychloroquine.

Attack on NAC.

Could they be any more obvious?

"After decades of being widely available in most retail stores, why the sudden crackdown?"

Why? Because it's an effective treatment for covid. I wanna see how they are going to prohibit quercetin and zinc, also effective treatments for covid, and Black Seed Oil, another effective treatment. Can they prevent an oil from being sold? Can they prevent a plant extract from being sold? FDA = marketing arm for Pharma. They do not work for the American people, they work for Pharma.

c19early.com