Eisai-Biogen to seek full approval for Alzheimer's immunotherapy Leqembi

Is the approval warranted given the prior controversies surrounding Adulhelm and regulatory capture?

On April 10 Reuters reported that the FDA is planning to hold a meeting in June to discuss full approval of the Alzheimer’s immunotherapy Leqembi (Lecanemab), which was developed in partnership between Japanese pharmaceutical company Esai and US-based Biogen.

Leqembi is intended to slow the progression of cognitive decline within the early stages of Alzheimer’s dementia. Given that the rate of AD is expected to increase as the number of elderly people increase, such therapies may be considered promising for an aging population.

Alzheimer’s is considered one of the biggest concerns in public health. However, with such concerns comes the possibility of pharmaceutical companies preying on the wants of the public.

Leqembi gained accelerated approval in January of 2023, but it came months after controversies surfaced in regards to Esai-Biogen’s prior AD immunotherapy Adulhelm (Aducanumab) received accelerated approval in 2021 with highly questionable data.

This accelerated approval also came weeks after a congressional report was released suggesting that Esai-Biogen did not go through the typical regulatory approval process for Adulhelm, with evidence suggesting that excessive meetings between FDA members and Biogen employees had occurred, and that Esai-Biogen was intending to target specific demographics for their highly expensive drug.

Keep in mind that Adulhelm was intended to come to market with an annual cost of around $56,000, but because insurance companies wouldn’t cover the cost Esai-Biogen reduced the cost by nearly half (~$28,200). It should be worth considering that a company is likely to still make a profit off of their pharmaceuticals, and so even at a price cut of nearly a half Esai-Biogen is likely to still be making money off of this immunotherapy- exactly how much did these immunotherapies cost to produce?

Strangely, Leqembi has a comparable annual price of $26,500, which raises questions as to whether Leqembi was intended to come to market with a price tag around $50,000 before Adulhelm’s had to be cut in half, but that’s speculation on my part.

Since many of these topics have been covered in prior posts, I’ll just raise the point that Esai-Biogen shouldn’t really be seen in the most positive light. Prior evidence has raised serious ethical questions towards how these drugs are being approved, and whether the evidence validates the ability to seek full approval with Leqembi.

As of now there is no cure for Alzheimer’s dementia, but that doesn’t mean that any treatment should be approved if it appears to provide even some benefit.

As a preventative agent, these immunotherapies would have to be considered within the longterm. Consider the cost, utility, and risk of serious adverse complications for someone who may be expected to take these therapies for years with evidence only showing a modest benefit of reducing the rate of cognitive decline.

Lasting Benefits of Leqembi?

In addition to Reuter’s reporting an article came out in CNBC last week with a rather interesting headline:

Given the fact that Leqembi is considered to be a preventative agent (i.e. slows the progression but doesn’t stop it), I was rather curious what it meant for patients to retain the benefits even after stopping the drug.

One may argue that a retention of benefits would infer that stopping Leqembi did not lead to a “return to baseline” i.e. that patients within the the Leqembi group did not have the same degree as cognitive impairment as those in the placebo group after stopping the treatment, but given the circumstances of dementia’s progression this seems like a rather strange argument to make (if it was the argument being made).

In essence, there probably wouldn’t be a rebound effect akin to someone who stops taking antihypertensives whose blood pressure then becomes elevated to levels prior to taking the medications.

Here’s how the CNBC article describes this “retention of benefits”:

The difference in disease progression rates between the Leqembi and placebo groups stayed the same during the gap period between treatments, according to the analysis. In other words, the disease continued to progress more slowly in patients who took Leqembi compared to the placebo group even during the period they were not taking the drug.

“The benefit that had been derived from being on treatment persisted,” Dr. David Russell, director of clinical research for the Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders, told CNBC.

“The disease was set back for a certain amount of time,” he added. “People get another year before they progress to a more moderate stage of disease compared to the people who didn’t get any treatment.”

The article draws data from a December 2022 study from McDade, et al.1

This study separated the use of Lecanemab into 3 time periods:

Study 201 blinded period: patients were blinded to what dose of Lecanemab they were given, or if they were in the placebo group. This time period lasted 18 months with primary endpoint measures taken at 12 months.

Gap Period: patients were taken off of either Lecanemab or placebo and measured for progression of cognitive decline for an average of 24 months post-blinded period, although the time period ranged from 9-59 months.

201 Open-Label extension (OLE): Patients who fulfilled the OLE inclusion/exclusion criteria were able to be provided the highest dose Lecanemab (10 mg/kg biweekly) following the Gap period. Note that this period included patients from either the placebo arm of the study as well as the 10 mg/kg biweekly group who were allowed to continue treatment.

Patients were assigned to either a placebo group or to 1 of 5 Lecanemab treatment groups:

2.5 mg/kg biweekly

5 mg/kg monthly

5 mg/kg biweekly

10 mg/kg monthly

10 mg/kg biweekly

As the discussion is focused on this supposed gap period the other aspects of the study will not be looked at (the end of this post will provide some information on the different biomarkers and tests conducted).

Suffice to say, the results of this gap section don’t appear to infer a retention of benefits, and instead notes that several biomarkers, including cognitive reports began to increase after stopping Lecanemab treatment:

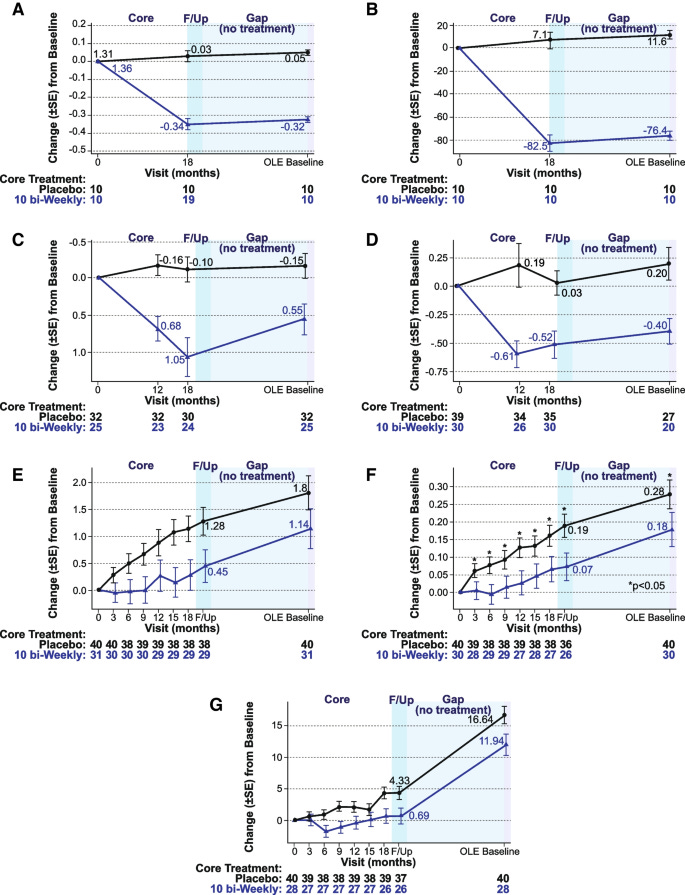

The above comes from Figure 7 and details some of the measurements taken in both the placebo group as well as the 10 mg/kg biweekly Leqembi group.

Values are relative to baseline, which is noted to start at 0. Note that the values should be interpreted based on what is being measured. That is, a higher plasma Aβ42/40 ratio relative to baseline is considered to reflect lower amyloid formation (7C) while higher p-tau181 values are correlated with worse AD and cognitive impairment (7D). Keep that in mind when reading the y-axis as the measures are different between each graph. 7A and 7B are results of amyloid PET SUVr and amyloid Centiloid imaging respectively.

Overall, the values here aren’t reflective of a retention of benefits, and in fact would suggest that halting of Leqembi appears to lead to accumulation of tau aggregates and amyloid proteins.

Some of the interesting findings can be seen in 7E-7G which were tests for cognition. Here, there appears to be parallel progression of cognitive decline between the placebo and the 10 mg/kg biweekly group. Note that these lines are suggested of rate of cognitive impairment, and care should be taken to assume perfectly parallel lines within this gap period. However, from a cursory glance the gap period appears to show a similar rate of cognitive decline in both groups which is reflective of the parallel-appearing lines.

What’s interesting is that the persistent gap may suggest that early treatment merely serves to delay the rate of progression. That is to say, treatment with Leqembi may delay the otherwise inevitable progression of Alzheimer’s dementia by a certain time period, and that those within the treatment group may have “bought” an additional few months.

McDade, et al. interpret these results in the following manner (emphasis mine):

While brain amyloid reaccumulated slightly as measured by PET during the gap period (by a mean of approximately 6 Centiloids), the soluble Aβ42/40 decreased (reaccumulated) by 47% and plasma p-tau181 levels increased (reaccumulated) by 24%. Over the gap period, the rates of clinical progression were similar between those treated with lecanemab and placebo in the core period, keeping the same absolute separation obtained at the end of treatment, but without further added benefit while off treatment.

So there’s a bit of wordplay going on here. It’s not necessarily that the disease continued to progress more slowly after treatment ended, but that the disease appears to progress in a typical fashion, just that those in the treatment group may have bought themselves some additional time before reaching the same degree of cognitive impairment as the placebo group. Note that I interpreted the phrase “continued to progress more slowly” as an indication of rate of cognitive decline, and not necessarily the level of cognitive decline.

Although this may seem a bit pedantic for something that would otherwise be typical media misinterpretations, consider that Esai-Biogen are attempting to seek full approval of Leqembi, and if such reports are misinterpreted then they may skew perception of these drugs as providing a benefit that is otherwise not presented in the data.

Keep in mind that the results of this study were argued to suggest long-term use of this drug, of which there is still long-term efficacy and safety unknowns:

Parallel decline in the gap period between the treated group and the placebo group may suggest that continued treatment is needed to achieve a continuing therapeutic benefit.

We also still have no actual evidence of the benefits of Leqembi aside from clinical markers.

There are also several issues with this study, including the fact that the gap period only collected information from the follow-up period as well as the beginning of the OLE phase of the trial, so the graphs within the gap period are likely to reflect the fact that data was collected from only two timepoints and really can’t provide any measures on clinical progression.

There’s also a rather egregious issue in the makeup of each treatment group when it comes to the gene ApoE4.

Apolipoprotein E is a lipoprotein with 3 polymorphic forms (ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4), all of which appear to contribute in some way to neurodegeneration. Current evidence suggests that carriers of ApoE4 may be at greater risk of Alzheimer’s dementia, as well as increased risk of earlier presentation of the disease. In contrast, ApoE2 is argued to possibly have a protective effect.

The exact dynamics of these lipoproteins have not been fully elucidated. It can be argued that ApoE2 having a protective effect may infer that heterozygous and homozygous carriers of ApoE4 may lack the same level of protection, and therefore are more susceptible to neurodegeneration. On the other hand, ApoE4 may also be more cytotoxic than ApoE2, and thus carriers may be more inclined to cellular/neuronal damage.

More can be found in a review from Safieh, et al.2.

And for those interested, it’s been recently reported that actor Chris Hemsworth found out that he was homozygous for ApoE4, leading up to consider early retirement from acting in order to focus on other aspects of his life.

All this to say, ApoE4 has been considered to be an indicator of early and more progressive Alzheimer’s dementia, and as such carriers may be more at risk relative to non-carriers.

Therefore, if one were to consider this gene in particular in a clinical trial, especially one intended to reduce the progression of Alzheimer’s, then wouldn’t it be considered important to have an even mix of carriers and non-carriers across all treatment groups?

Apparently, this trial did not appear to randomize ApoE4 carriers in an even manner. Strangely, the placebo group appears to have a very low percentage of non-carriers compared to the makeup of the highest dose group (10 mg/kg biweekly):

Essentially, the highest treatment group is comprised largely of non-carrier patients. One has to wonder if the slower progression of disease in this group may partially be contributed to the low number of ApoE4 carriers in this group. Note that the placebo group appears to have a nearly reversed proportion of carriers/non-carriers.

This raises questions as to whether this may have influenced the outcomes, as the authors note that ApoE4 carrier status is a significant covariate for PET SUVr results.

As Esai-Biogen seek full approval, remember that approval should be based on clear, overwhelming evidence towards the benefits of the therapeutic. So far there still is no long-term safety and efficacy data.

For those interested in some information on these biomarkers I’ve included some additional information below.

plasma Aβ42/40 ratio: amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides are considered to be the pathological agent in Alzheimer’s dementia. The peptides come in various isoforms, with the number noting the peptide length (42 notes that Aβ42 is 42 amino acids long). These two isoforms are considered to be the most important. However, because the measures of these plaques vary it’s been argued that a ratio better serves as a differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s with respect to other neurodegenerative disease. In general, it’s been argued that Aβ42 levels decline in AD progression, and thus a lower ratio would suggest greater disease progression.

More information can be found in a review from Hansson, et al.3

Keep in mind that Aβ42 levels in blood may not correlate with levels found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Studies may also utilize different methods, such as mass spectrometry or an immunoassay which may require different interpretations.

P-tau181: Tau proteins are microtubular-associated proteins that are assumed to be associated with neurodegeneration. Tau proteins may become hyperphosphorylated (phosphates added), and it’s assumed that these additional phosphate groups aid in the aggregation and neurofibrillary tangles of these proteins. In particular, evidence has suggested that phosphorylation of tau at the threonine position 181 (hence p-tau181) serves as a good indicator of AD progression and may be a better predictor of AD, as some evidence suggests that phosphorylation of these tau proteins may occur in response to amyloid-Beta formation.

More information on tau proteins can be found in this review from Alonso, et al.4.

Additional information on biomarker diagnostic tests can also be found in a review from Iaccarino, et al.5

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

McDade, E., Cummings, J.L., Dhadda, S. et al. Lecanemab in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease: detailed results on biomarker, cognitive, and clinical effects from the randomized and open-label extension of the phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Alz Res Therapy 14, 191 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-01124-2

Safieh, M., Korczyn, A. D., & Michaelson, D. M. (2019). ApoE4: an emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. BMC medicine, 17(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1299-4

Hansson, O., Lehmann, S., Otto, M., Zetterberg, H., & Lewczuk, P. (2019). Advantages and disadvantages of the use of the CSF Amyloid β (Aβ) 42/40 ratio in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimer's research & therapy, 11(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-019-0485-0

Alonso AD, Cohen LS, Corbo C, Morozova V, ElIdrissi A, Phillips G and Kleiman FE (2018) Hyperphosphorylation of Tau Associates With Changes in Its Function Beyond Microtubule Stability. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12:338. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00338

Iaccarino, L., Burnham, S.C., Dell’Agnello, G. et al. Diagnostic Biomarkers of Amyloid and Tau Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Overview of Tests for Clinical Practice in the United States and Europe. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2023). https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2023.43

Thanks for this article.

I was always skeptical of drugs that affect dementia and cognition. But I had a patient with severe Alzheimer's and I forget what drug she took but it made a significant difference.

Thanks for this article.

I was always skeptical of drugs that affect dementia and cognition. But I had a patient with severe Alzheimer's and I forget what drug she took but it made a significant difference.