Well, it’s that time of year again. Halloween has come and gone, the last few leaves are being blown off of trees with a sudden windy autumns, and most importantly Thanksgiving is fast approaching.

For those not in the know Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated in the US (as well as a few other countries) intended to once celebrate the bountiful fall harvest and giving thanks for said bounties. It’s a time when families get together and eat copious amounts of food, usually signaling the start of the Christmas shopping season. In the US it falls on the fourth Thursday of November, meaning this year Thanksgiving is on the 24th which I, of course, was completely oblivious to.

It’s also the time for that daughter of a distant relative to yell about Indigenous genocide and colonialism while your relatives wonder what they’re paying for at university, but it only happens once a year (hopefully) and you and everyone else just decide to put up with it.

Anyways, although many families have different ways of celebrating Thanksgiving the star tends to be the good old roasted turkey, which may come with complaints of dry breast meat and underdone thighs. But of course, all of the other fixings tend to have a shining role as well—I’m one of those people that actually likes stuffing/dressing.

It’s not uncommon that post-Thanksgiving indulgence comes with a sudden wave of sleepiness and loosening of belts.

Disregard any notion of making dieting during the holidays a thing!

The banality of post-Thanksgiving dinner sleepiness has raised the all-too important question of what exactly makes one sleepy after such gluttonous feasting?

One popular suggestion implicates the turkey, and more importantly the amino acid Tryptophan as being the reason for such sleepiness.

But is turkey and tryptophan to blame, or is this a product of modern myths and misconceptions at work?

What is Tryptophan?

Tryptophan (W) is one of the 20 amino acids used as the building blocks of proteins and enzymes.

Tryptophan comes from the long-chain neutral amino acid (LNAA) group of amino acids due to the bulky, aromatic sidechain.

It’s also considered one of the 9 essential amino acids as our body does not produce it endogenously and requires continuous replenishment from food sources.

How the body uses tryptophan

But tryptophan isn’t the critical molecule for this sleepiness phenomenon, but rather it’s the molecules it synthesizes that are the critical players.

Tryptophan is used by the body as a precursor for two critical molecules: serotonin and melatonin.

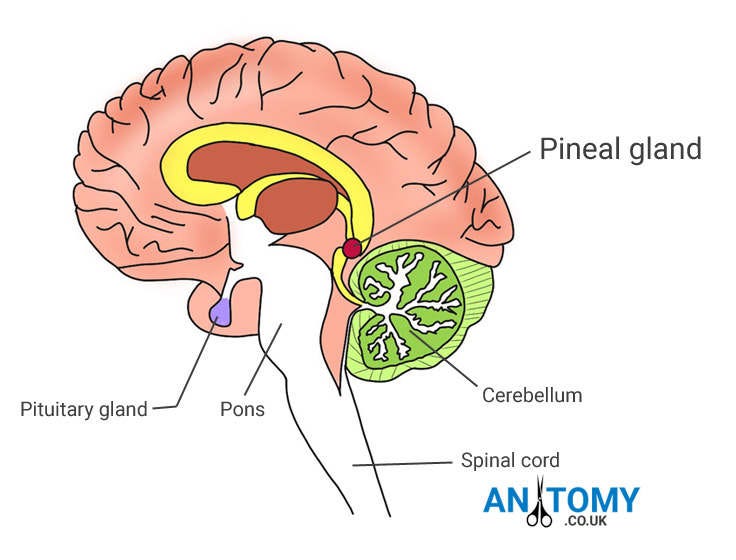

After consumption of tryptophan-rich foods, tryptophan makes its way to the brain (predominately the pineal gland1) where biosynthesis of serotonin is undertaken with the eventual construction of melatonin.

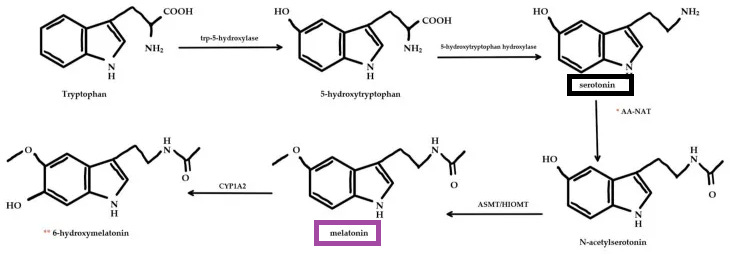

The synthetic pathway is described and illustrated below from a review by Vasey, et al.2:

Endogenous melatonin is synthesized in the pinealocyte, and other tissues, where it is an end-product of tryptophan and serotonin biosynthetic pathways (Figure 3). Initially, tryptophan is transported into the cell, where it is acted on by tryptophan-5-hydroxylase and 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase enzymes to form serotonin [30]. Depending on adrenergic neuronal input, serotonin is acetylated by arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) then methylated by “acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase (ASMT, also called hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase or HIOMT)” to form melatonin [30]. AA-NAT is the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of melatonin [30].

Therefore, it’s not tryptophan per se that is responsible for the sleepiness, but rather it’s argued that the consumption of tryptophan will lead to the production of both serotonin and melatonin, causing the sleepiness.

Is turkey really the problem?

The assumption above tends to be used as a rational for relating turkey to the Thanksgiving food coma.

However, this relationship is more of a conflation with a hint of sounding “sciencey” enough to be taken as true.

In reality, the conversion of tryptophan to melatonin is highly complex.

Remember that melatonin synthesis is intrinsically tied to light exposure, such that shorter wavelengths of light are needed to stimulate its production. It’s one of the reasons why constant exposure to blue light via technology and artificial indoor light can disrupt sleep patterns.

Vasey, et al. notes this in their review:

Melatonin is known to play a role in promoting a sleep state. Therefore, absent or reduced melatonin levels should perpetuate an awake state. It is already known that exposure to light, especially high wavelength light, suppresses circulating melatonin in the blood [11]. Suppression of plasma melatonin is thought to result from the inhibition of melatonin synthetic enzymes like N-acetyltransferase in the pineal gland that are under the influence of external light [11]. Normally, this process inhibits sleepiness during the day when diurnal humans need to be active. However, exposure to high wavelength light during abnormal times disrupts circadian rhythms and inappropriately suppresses melatonin synthesis and secretion in the pineal gland.

It’s likely that all of the light exposure from phones, televisions, and indoor lighting would have an effect in attenuating melatonin production.

That doesn’t even take into account the fact that other meats and foods are high in tryptophan, and therefore doesn’t make turkey unique in that regard.

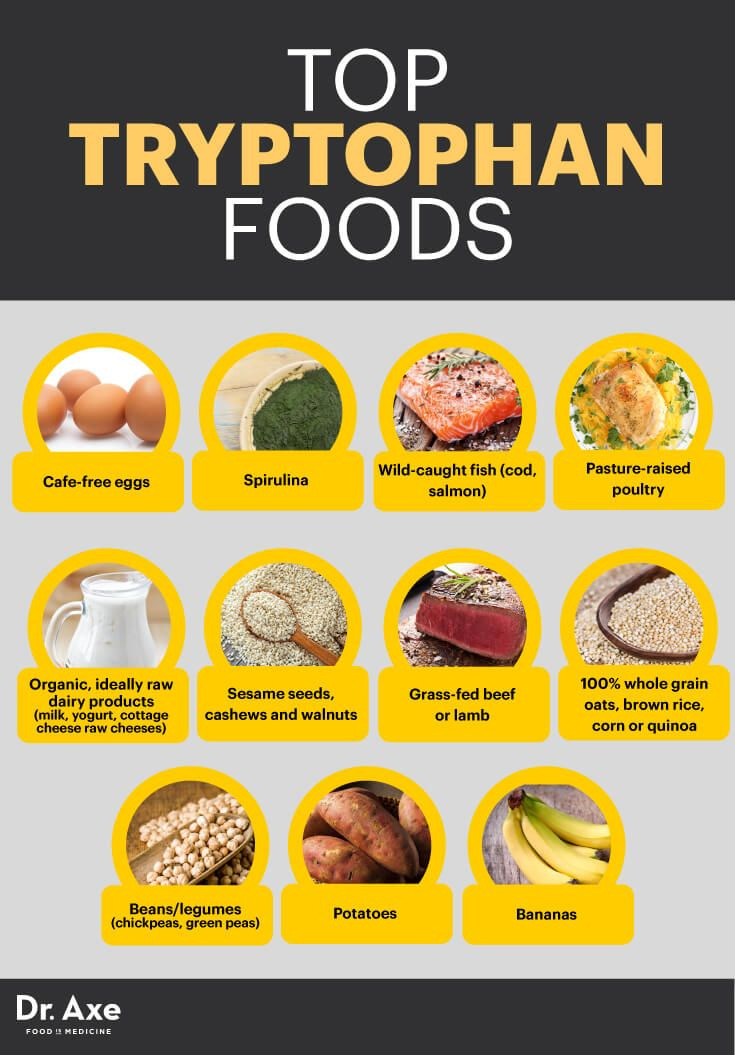

The image below lists some of these common food sources:

Strasser, et al.3 notes a few common plant sources of tryptophan in their review:

Foods known to be high in tryptophan comprise nuts such as cashews, walnuts, peanuts, and almonds; seeds such as sesame, pumpkin, and sunflower seeds and soybeans and grains such as wheat, rice, and corn.

Pereira, et al.4 also makes a comment about meat sources and tryptophan, albeit through inferences:

The modern protein-abundant dietary pattern, rich in meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and milk, is associated with improved sleep quality, probably because of its high content of tryptophan and also of vitamin B12, which seems to aid in the regulation of sleep besides contributing to melatonin effects, being able to increase its synthesis and number of its brain receptors (Yu et al., 2017).

Ironically, given that both cereal and milk contain high levels of tryptophan we may implicate that the staple breakfast combination may actually be a strong inducer of sleep.

It’s hard to find any actual discussions of meat sources rich in tryptophan in science literature, however we can surmise that foods rich in melatonin should also be rich in tryptophan due to serving as a precursor, which would then even include foods such as strawberries, grapes, and even wine as being melatonin-rich products (I guess watch for the winos in the family?).

Interestingly, during the late 1960s several hypotheses came out suggesting that a low tryptophan diet may help with psoriatic arthritis. One case report from Spiera, H. & Lefkovits, A.M, 19675, in which patients with psoriasis had typical meat replaced with turkey meat for a “low tryptophan” diet showed remission of symptoms.

It was later noted by the same researchers that their assessment of tryptophan levels in turkey was off6 and the remissions may not have been owed to a low tryptophan diet. This likely came about due to inability to reproduce such findings by other researchers, as well as some criticisms in regards to the quantification of tryptophan.7 However, it’s interesting that at one time it was assumed that turkey was a “low tryptophan” food.

And so turkey is likely not to be the only food at your Thanksgiving table rich in tryptophan. It wouldn’t seem fitting to place the blame solely on the animal that has both hands and other aromatics shoved up its rear end for our delights—the turkey has already been through enough trauma.

It’s also worth noting that the shuttling of tryptophan to the pineal gland is also attenuated by intake of other proteins, as tryptophan must compete with other LNAAs for transport across the blood-brain barrier. Foods rich in tryptophan are also likely to be rich in other amino acids such as LNAAs, which would alter the tryptophan/LNAA ratio and make it more difficult to transport tryptophan out of plasma into the brain.

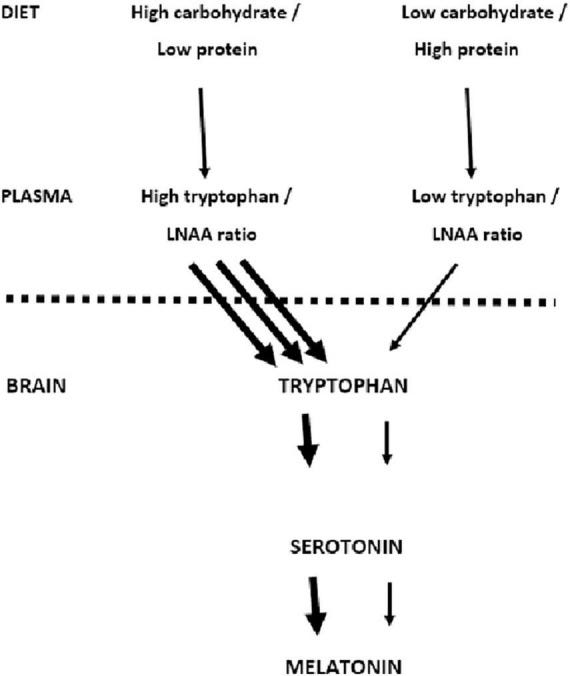

Apparently, even carbohydrates may influence the transport of tryptophan across the brain as high carbohydrate diets can aid in the uptake of tryptophan into the brain.

A review from Benton, et al.8 notes the following:

Carbohydrate-induced increases in blood glucose have been said to increase the uptake of tryptophan by the brain (18), increasing the synthesis of serotonin and melatonin. For example, when Binks et al. (8) reviewed the influence of diet on sleep, they proposed that a major factor was the ability to vary the activity of brain serotonin and hence increase melatonin production. Fundamental to this suggestion is the work of Fernstrom and Wurtman (18). Consuming carbohydrate rapidly increases the levels of blood glucose with a consequent release of insulin, which causes muscle to take up Long Chain Neutral Amino Acids (LNAA—tyrosine, phenylalanine, leucine, isoleucine, valine). An exception is tryptophan which binds to albumin and remains in the blood.

So the effect here consists of a dynamic interaction between the ratio of LNAAs and carbohydrates. A low protein diet may keep the tryptophan/LNAA ratio high. The ingestion of a high number of carbs may then help sop up the other LNAAs leaving tryptophan available for crossing into the brain.

Benton, et al. provides the following diagram illustrating this dynamic:

All this to say that the high consumption of carbohydrates may be more implicated in the sleepiness most people feel, although it’s important to remember that the interaction here is rather complex and the above diagram is a mere hypothesis. Turkey also contains far more than just tryptophan and so this tryptophan shuttling diagram may not work out in favor of producing melatonin.

Again, welcome to complex systems!

Don’t blame the gobbler

And so it appears that a lot of the rumors around turkey isn’t all that it’s gobbled out to be. The evidence clearly suggests a more complex dynamic where far more than the turkey should be looked at in causing that sleepy, fatigued sleeping.

It’s interesting that many articles have come out disabusing this rumor, and yet the rumor still persists. Thus is the strong nature of gossip, or maybe it’s just something to be used as for small talk with those relatives you’d rather not speak to.

In any case, don’t fret over the sleeper agent turkey. The pumpkin pie or the half a bottle of chardonnay can be just as likely to make you sleepy.

Just remember to balance indulgence and moderation, and more importantly remember that it’s about family, and about being in the company of those you love, or at least those you put up with.

Hey, that’s how family goes right? 🤷♂️

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Vasey, C., McBride, J., & Penta, K. (2021). Circadian Rhythm Dysregulation and Restoration: The Role of Melatonin. Nutrients, 13(10), 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103480

Strasser, B., Gostner, J. M., & Fuchs, D. (2016). Mood, food, and cognition: role of tryptophan and serotonin. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 19(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000237

Pereira, N., Naufel, M.F., Ribeiro, E.B., Tufik, S. and Hachul, H. (2020), Influence of Dietary Sources of Melatonin on Sleep Quality: A Review. Journal of Food Science, 85: 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.14952

Spiera, H., & Lefkovits, A. M. (1967). Remission of psoriasis with low dietary tryptophan. Lancet (London, England), 2(7507), 137–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(67)92970-4

Spiera, H., & Lefkovits, A. M. (1967). Turkey, tryptophan, and psoriasis. Lancet (London, England), 2(7531), 1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(67)93046-2

Caplan RM. The Low-Tryptophan Diet In Psoriasis. JAMA. 1969;207(4):758. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03150170084026

Benton, D., Bloxham, A., Gaylor, C., Brennan, A., & Young, H. A. (2022). Carbohydrate and sleep: An evaluation of putative mechanisms. Frontiers in nutrition, 9, 933898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.933898

Fascinating scientific exploration of Turkey Day food coma!

Yams are my go-to food for getting back to sleep quickly after waking up hard in the wee hours (but only if I can't sleep in; even semi-retirement is good that way). Turkey, not so much, but half the foods in that list of high-tryptophan foods are staples of mine. They all seem to help with getting back to sleep.

We're weird around here. We don't stuff ourselves at Thanksgiving, and more or less don't eat things we shouldn't, and aren't more sleepy after that meal than any other, so I don't know. But I did have a sandwich with turkey, bacon, and avocado at lunch yesterday, eating out, and oh did I sleep well that afternoon. Maybe it was the gluten-free bread?