In yesterday’s post I made a quip that moving forward we’re likely to not have any studies including unvaccinated (both uninfected and naturally immunized) individuals.

Luckily, it appears that doesn’t seem to be the case just yet. Last week a preprint study was published online that looked specifically at unvaccinated Qatari individuals who were infected by COVID and examined their reinfection rates.

I was made aware of this study by one of Dr. MoBeen’s streams:

This is a pretty important study since it measures reinfection rates both before and after the Omicron emergence. For many of us, this study is extremely important because it provides some evidence outside of the context of vaccination- something that is extremely wanting during these times.

It’s fortunate that Qatar appears to be one of the only countries that continues to conduct this type of study.

Into the Study

The study comes from Chemaitelly, et. al.1 and was published online just recently in medRxiv.

The researchers wanted to answer the following questions:

We sought to answer three questions of relevance to the future of this pandemic: 1) When infected with a pre-Omicron variant, how long does protection persist against reinfection with pre-Omicron variants? 2) When infected with a pre-Omicron variant, how long does protection persist against reinfection with an Omicron subvariant? 3) When infected with any variant, how long does protection persist against severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19? Answers to these questions help us to understand duration of protection resulting from natural-infection, effects of viral evasion of the immune system on this duration, and effectiveness of natural infection against COVID-19 severity when reinfection occurs.

Again, this is a pretty critical study for those of us who are curious about our natural immunity.

Using data from millions of Qatari residents the researchers matched patient information based on infection history (via testing, hospitalization, etc.) as well as different demographics:

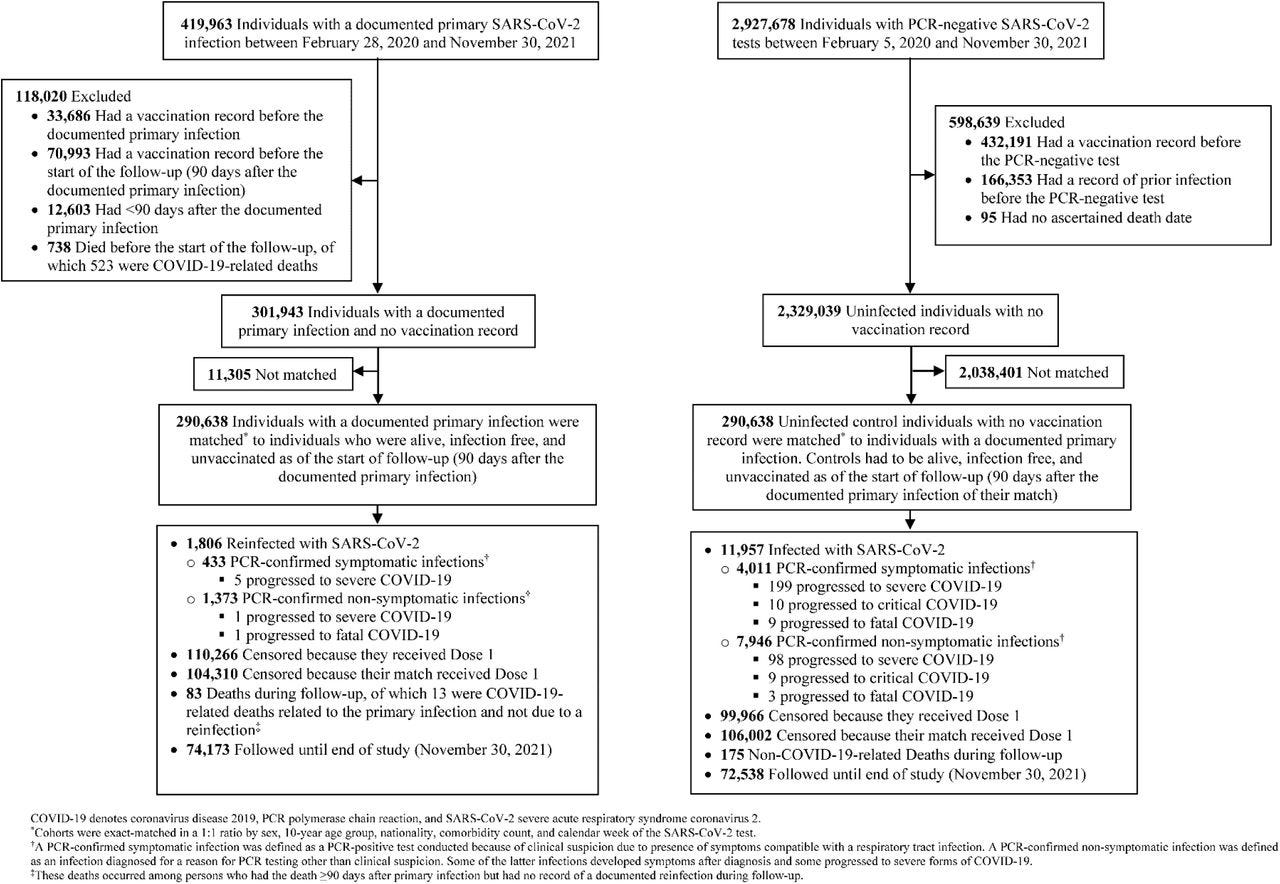

Individuals in the primary-infection cohort were exact-matched in a one-to-one ratio by sex, 10- year age group, nationality, and comorbidity count (none, 1-2 comorbidities, 3 or more comorbidities) to individuals in the infection-naïve cohort, to control for differences in risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar.19, 24–27 Matching by these factors was shown to provide adequate control of differences in risk of infection.4, 28–31 Matching was also done by the calendar week of SARS-CoV-2 testing. That is, an individual who was diagnosed with a primary infection in a specific calendar week was matched to an infection-naïve individual who had a record of a SARS-CoV-2-negative test in that same week (Figures S1-S3). This matching ensures that all individuals in all cohorts had active presence in Qatar at the same calendar time. Matching was performed using an iterative process so that each individual in the infection-naïve cohort was alive, infection-free, and unvaccinated at the start of follow-up.

An example of the cohort matching can be seen below. Note that those with any recorded vaccination history was censored and removed from the analysis:

In the end, the researchers used two cohorts- one who was previously infected with a pre-Omicron strain as well as those who were infection-naïve. Three different “trials” were conducted based on the questions raised above comparing these two cohorts.

For the sake of our current Ba.4/Ba.5 predicament, I think the first two studies are the ones most people would be interested in.

As a comparative analysis, we can argue that a prior infection should be akin to vaccination (2-doses) and that reinfection would be similar to infection as seen within the clinical trials.

Pre-Omicron Reinfection Study

When examining reinfection rates prior to the Omicron wave the researchers had these results (emphasis mine):

There were 1,806 reinfections in the primary-infection cohort during follow-up, of which 6 progressed to severe and 1 to fatal COVID-19 (Figure S1). Meanwhile, there were 11,957 infections in the infection-naïve cohort, of which 297 progressed to severe, 19 to critical, and 12 to fatal COVID-19. Cumulative incidence of infection was 1.7% (95% CI: 1.6-1.8%) for the primary-infection cohort and 9.6% (95% CI: 9.4-9.9%) for the infection-naïve cohort, 15 months after the primary infection (Figure 1A). […]

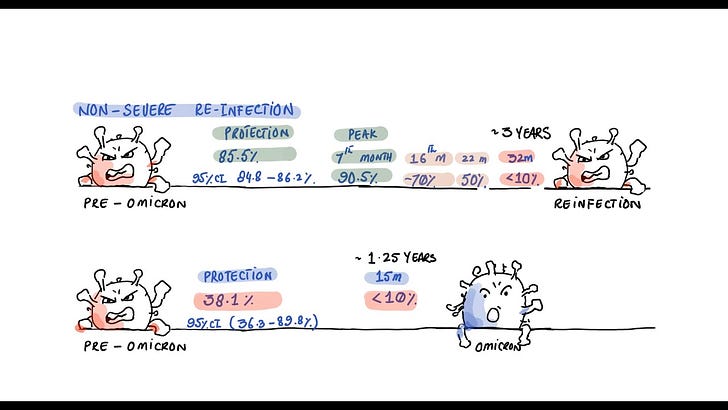

Effectiveness of pre-Omicron primary infection against pre-Omicron reinfection was 85.5% (95% CI: 84.8-86.2%). Effectiveness increased slowly after the primary infection and reached 90.5% (95% CI: 88.4-92.3%) in the 7th month after the primary infection (Figure 2A). Starting in the 8th month, effectiveness waned slowly and reached ∼70% by the 16th month. Fitting the waning of protection to a Gompertz curve suggested that effectiveness reaches 50% in the 22nd month and <10% by the 32nd month (Figure 3).

This 85.5% is the number we can compare to the vaccine clinical trials. Remember that both Pfizer and Moderna indicated that their vaccine efficacy rate was in the 90th percentile. Compared to the vaccines, this number is actually pretty good.

BUT, remember that the vaccine trials looked at relative risk reduction (RRR), and not absolute risk reduction (ARR)2. As I indicated in my prior post on RRR and ARR, I indicated that Pfizer’s clinical trial showed an RRR value of around 95%, yet their ARR value was around 0.8%.

ARR is generally considered to be a more important factor than RRR when accessing the effectiveness of a drug or vaccine.

This should remind us to be a bit cautious with the data above and looking at that 85.5%, because that 85.5% is an indication of RRR, not ARR.

However, considering that we are well-versed in the differences between RRR and ARR, we can conduct our own calculations and see if the ARR values are comparable between vaccines and natural immunity.

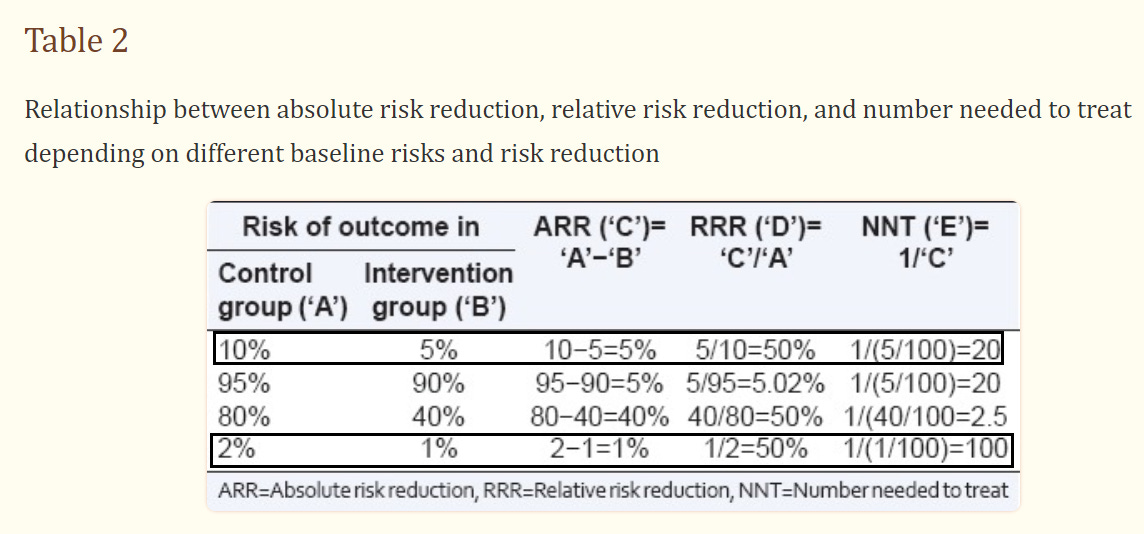

I’ll show the calculations below for ARR, but follow along and see if you can calculate the values yourselves using the following table (you can also follow along with my calculations for the Pfizer trial from the RRR vs ARR post- I’ll show my calculations for how the Qatari researchers reached their 85.5% RRR in the footnote below3):

So we would first need the risk outcome values. The researchers provided it in the above excerpt:

There were 1,806 reinfections in the primary-infection cohort during follow-up, of which 6 progressed to severe and 1 to fatal COVID-19 (Figure S1). Meanwhile, there were 11,957 infections in the infection-naïve cohort, of which 297 progressed to severe, 19 to critical, and 12 to fatal COVID-19.

Each cohort contained 290,638 patients, so that will be our denominator (number of participants).

Calculating Risk Outcome:

For the control (naïve group, or ‘A’) we can take the 11,957 infections and divide it by the participants:

11,957(naïve infected) / 290,638 (patients) = 0.04114, or 4.114%

We can then do the same for the prior-infected group (‘B’)of 1,806. Remember, the patient number here is the same:

1,806 (reinfections) / 290,638 (patients) = 0.006214, or .6214%

ARR Value (‘C’)

Now that we have our risk for each group, we can just subtract the percentage of reinfections (.6214%) from the percentage of naïve infections (4.114%) to get our ARR value (‘C’):

4.114% (naïve risk) - 0.6214% (reinfection risk) = 3.4926% ARR

ARR values are generally going to be low within this context, which suggests that the risk of infection early on during the prior strains was not very high.

However, compare this 3.4926% ARR after natural immunity to the .8344% ARR based on Pfizer’s own clinical data.

That’s about an order of 4X different4 between the two, and comparatively speaking ARR is a more important indicator.

This would, in some sense, suggest that naturally immunity may offer greater protection than vaccine alone within this context.

However, remember the important mantra: is the risk warranted?

For those of us who are naturally immunized, this may speak well on our behalf. However, we always have to consider if the risk of infection and severe disease outweighs the benefits of natural immunity for those who haven’t gotten sick yet.

Keep that in mind when looking at this ARR value. Also, remember that many variables are likely to lead to the ARR value above, such as control measures and differences in social/cultural interactions could also greatly influence the above ARR value. It may be considered improper to do the analysis above given the differences in cohort.

If I wanted to be more consistent, I would probably use data from a clinical trial in Qatar for Pfizer since those results would be far more comparable to this situation, however I used the Pfizer data since I calculated that previously5.

So judging from the RRR value alone, naturally immunity may seem comparable to vaccinated. However, on the basis of ARR there appears to be some evidence that naturally immunity will fare better- well, at least within the context of reinfection prior to Omicron (more consistent evidence is needed).

Omicron Reinfection Study

For this section, we can’t quite make a comparison to the vaccine clinical trials because we would essentially need a re-reinfection group to measure (technically, the reinfection group would be considered the “booster” group within this context, so in order to test natural immunity “booster” protection we would need to have a study with a 3rd infection cohort).

So we’ll leave that comparison alone for now. However, the results do provide an interesting paradox:

There were 7,995 reinfections in the primary-infection cohort during follow-up, of which 5 progressed to severe COVID-19 (Figure S2). Meanwhile, there were 12,230 infections in the infection-naïve cohort, of which 26 progressed to severe, 7 to critical, and 5 to fatal COVID-19. Cumulative incidence of infection was 6.8% (95% CI: 6.7-6.9%) for the primary-infection cohort and 10.4% (95% CI: 10.2-10.6%) for the infection-naïve cohort, 165 days after the start of follow-up (Figure 1B).

The overall adjusted hazard ratio for infection was 0.62 (95% CI: 0.60-0.64; Table 3). Effectiveness of pre-Omicron primary infection against Omicron reinfection was 38.1% (95% CI: 36.3-39.8%). Effectiveness varied for the primary-infection sub-cohorts (Figure 2B). It was ∼60% for those with a more recent primary infection, between June 1, 2021 and November 30, 2021, during Delta-dominated incidence.4, 34, 35 Effectiveness declined with time since primary infection and was 17.0% (95% CI: 10.1-23.5%) for those with a primary infection between December 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021, during Alpha-dominated incidence.4, 34, 35 However, higher effectiveness of ∼50% was estimated for those with a primary infection before August 31, 2020, during original-virus incidence (note discussion in Section S3).4, 34, 35 Fitting the waning of protection to a Gompertz curve suggested that effectiveness reaches 50% in the 8th month after primary infection and <10% by the 15th month (Figure 3).

Effectiveness of pre-Omicron primary infection against severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19 due to Omicron reinfection was 88.6% (95% CI: 70.9-95.5%; Table 3). In the additional analysis restricting the matched cohorts to the sub-cohorts ≥50 years of age (6,304 individuals), effectiveness against reinfection and against severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19 reinfection was 21.6% (95% CI: 11.1-31.0%) and 84.6% (95% CI: 59.7-94.1%), respectively. In the sensitivity analysis adjusting the overall hazard ratio by the ratio of testing frequency, effectiveness against reinfection was 31.7% (95% CI: 29.7-33.6%). More results are in Section S3.

In keeping with the pre-Omicron section, I wanted to capture the important information from the Omicron reinfection section (above) intact.

We can see that the RRR value during the Omicron wave was around 38% if one were previously infected, which doesn’t seem like much protection. But this does make sense give the supposedly high immune escape that came with Omicron. Prior to this study there wasn’t much evidence in the way of natural immunity- we only knew of immune escape in those who were vaccinated6.

However, this evidence helps to validate the idea that Omicron differs so greatly from prior variants that nearly everyone can get infected with Omicron, regardless of immunization status (vaccine vs. natural).

But I think what’s most interesting is the reduced severity noted in the 3rd paragraph. It sounds a bit familiar, right?

“These are sterilizing vaccines!”

“Breakthrough infections are very rare!”

“The vaccines don’t stop the transmission, but they stop severe illness!”

The last point is the one that’s important here, as the researchers suggest that prior infection may not stop transmission of Omicron, but may aid in reducing its severity (similar to the vaccines).

As noted in the researchers’ Discussion:

Despite waning protection against reinfection, strikingly, there was no evidence for waning of protection against severe COVID-19 at reinfection. This remained ∼100%, even 14 months after the primary infection, with no appreciable effect for Omicron immune evasion in reducing it.

This pattern also mirrors that of vaccine immunity, which wanes rapidly against infection, but is durable against severe COVID-19, regardless of variant.4, 6–8, 30

Aside from the multitude of caveats needed to make the comparison, I think it’s rather interesting that these results somewhat mimic those we are seeing with vaccinations. This study sheds further light into an area that would otherwise be left untouched, and given this information it’s rather surprising that the remarks here a similar to those made with the vaccines.

In Regards to Seasonal COVID

Throughout the study the researchers posited whether COVID may be somewhat characteristic of other seasonal coronaviruses:

Seasonal “common-cold” coronaviruses are characterized by short-term immunity against mild reinfection,10 but long-term immunity against severe reinfection.2 While SARS-CoV-2 infection with the original virus or pre-Omicron variants elicited >80% protection against reinfection with the original virus11–13 or with Alpha (B.1.1.7),14 Beta (B.1.351),15 and Delta (B.1.617.2)16 variants, protection against reinfection with Omicron subvariants is below 60%.16, 17 Reinfections have become common since Omicron emergence.17

And within the Discussion they make a similar reference as well:

Infection with common-cold coronaviruses, and perhaps influenza,38 induces only a year-long immunity against reinfection,10 but life-long immunity against severe reinfection.2 To what extent this pattern reflects waning in biological immunity or immune evasion with virus evolution over the global season is unclear. Above results suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may exhibit a similar pattern to that of common-cold coronaviruses within few years. Short-term biological immunity against reinfection of 3 years may decline as a result of viral evolution and immune evasion, leading to periodic (possibly annual) waves of infection. However, the lasting immunity against severe reinfection will contribute to a pattern of benign infection. Most primary infections would occur in childhood and would likely not be severe. Adults would only experience periodic reinfections, also not likely to be severe.

Consider that the mainstream narrative for the first year or so was that zero-COVID was a possibility as long as stricter and stricter measures were put into place.

However, the Omicron era has now caused doctors to respond as if COVID is now behaving like a seasonal cold or flu.

I suppose the more mild nature of Omicron made it more palatable to suggest a seasonal nature to COVID (if it does come) in order to attenuate zero-COVIDians, but part of me doesn’t think it was Omicron that made the virus “seasonal”, but that seasonality is the likely end goal of COVID. That includes the possibility of reinfections for everyone- something that I originally did not consider, but later thought otherwise via my reinfection post:

It’s also something that Dr. MoBeen reiterates in his video, in which he remarks that seasonal COVID is the end goal (of which he has thought since the beginning of COVID).

Even more important, it at least suggests that COVID may be more comparable to other upper respiratory infections- something that tends to be dismissed in various avenues of discourse.

We’re dealing with a lot of noise that makes it difficult to figure out the appropriate signals, but as more information accumulates it appears that the likely end goal will result in seasonal COVID.

Concluding Remarks

In the era of vaccinate everything, it’s pretty refreshing to see a study that takes into account those who have not been vaccinated.

Whether these results will upset vaccinated or unvaccinated individuals, it’s interesting that the results here parallel those seen within vaccinated cohorts.

Protection from reinfection seems comparable to that seen within the literature in regards to vaccination, which is something that has been a point of contention all around, even though the literature eventually made similar remarks.

But what’s most interesting is the waning immunity in the face of Omicron, which just highlights the fact that Omicron is so distinct from Delta that most forms of protection either waned or depleted with the Omicron wave.

The researchers note that waning immunity is likely to occur in both forms of immunization, but that natural immunity may last somewhat longer.

In short, this study provides some promising evidence in regards to natural immunity, but as it compares to vaccinated individuals the information isn’t so clear due to some of the comparable results. Further studies are needed, especially in the wake of Omicron, in order to make such an assessment.

We should only hope that more studies on natural immunity may come in the future.

Limitations

I do want to include a bit about some limitations to this study. This tends to be an overlooked area but it provides the necessary caveats when assessing studies.

For instance, note that the study based vaccinated/unvaccinated status on reported vaccinations, so there could be instances in which a vaccinated individual made their way into the study. This would depend on the health surveillance nature of Qatar, and whether they enforce mandatory collection of data. This is one thing to keep in mind.

Also, positivity was not measured based on seroprevalence of antibodies such as anti-Nucleocapsid antibodies. Therefore, it’s likely that naturally-immunized participants may have been included in the study as well. The researchers note this:

We investigated incidence of documented infections, but other infections may have occurred and gone undocumented. Undocumented infections confer immunity or boost existing immunity, thereby perhaps affecting the estimates (note Section S3).

There’s also the matter of what constitutes a reinfection. As the researchers remarked, reinfection was defined as another infection happening 90 days after the initial infection:

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection is conventionally defined as a documented infection ≥90 days after an earlier infection, to avoid misclassification of prolonged PCR positivity as reinfection.12, 13, 16 Therefore, each matched pair was followed from the calendar day an individual in the primary- infection cohort completed 90 days after a documented primary infection.

This appears to be the traditional method of defining reinfection, but keep this in mind that this excludes people who may have been reinfected before the 90 days. If you look at other studies that compare reinfections, make sure to see how they define it- it may not be the same as it is defined in this study.

Lastly, I’ll provide a limitation to my ARR value. As I noted above, the two cohorts I’m comparing (Pfizer clinical trial vs the Qatar study) are likely to be very different from one another. Multiple variables are likely to influence the ARR value from each study, and so the 4X magnitude difference is likely to be incorrect. Keep those caveats in mind when looking at that value.

With that, I’d like to know what you all think of the study. Is this comparable to natural immunity? Was there some things missed in this study? Please let me know below!

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Chemaitelly H, Nagelkerke N, Ayoub HH, et al. Duration of immune protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection in Qatar. medRxiv; 2022. DOI: 10.1101/2022.07.06.22277306.

Remember that RRR is measured based on the point of contact, similar to the seatbelt analogy. At the point you get exposed (or in an accident) how likely are you to be protected?

ARR is different, as it takes into account the probability of the event taking place in the first place. So although RRR may indicate that you are well-protected at the point of exposure, ARR will tell provide context as to how likely you are to be exposed in the first place.

This requires a bit of cheating because you generally conduct calculations that provide you with the ARR before the RRR value. Therefore, we can use the values calculated for ARR above to get our RRR value:

Take the ARR value (3.4926%) and divide it by the ‘A’ value (4.114%). Note that I’m using percentages here to keep the units the same. I will have to convert the final value into a percentage afterwards.

3.4926% ARR / 4.114% ‘A’ = 0.8490, or 84.90% RRR

Keep in mind that I’m using different significant figures from the researchers, so my percentage is slightly off. However, it’s still pretty close to what they got above.

3.4926 (ARR natural immunity) /.8344 (ARR Pfizer clinical trial) = 4.186, or roughly a factor of 4 difference.

If anyone has longitudinal data on a Qatar clinical trial with Pfizer that could be more comparable, please let me know in the comments. Thanks!

I can’t find any data on Israel and breakthrough infections with a large cohort analysis. If anyone has a study that can show waning protection with Omicron and 2-dose please link it in the comments. Thanks!

After posting, I probably should have asserted that this at least suggest that vaccines are not better than natural immunity- they are at least comparable, with the slight caveat that natural immunity may have a better ARR, or may not wane as suddenly as vaccinated.

I suppose if we want to get antagonistic, us natty folk can circle around the vaccinated and chant "one of us":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mRe8J4scGtU

Very interesting! When I read these kinds of studies, I always remind myself that PCR tests sometimes are false positive, giving something like 2% false positives. So if you test 1,000 people three times, you would get incidence of 60, or 6% or so, even if none of them had Covid.

This brings up a question that is actually burning in my mind: WHAT IS A REINFECTION?

For example, let's say that I, a previously infected unvaccinated individual, come in close contact with an ill person. Am I "reinfected" if I test positive some time later, despite having no symptoms?

The reason for my question is that last winter, my wife had Covid and I took care of her and did not get ill. After a week or so, I realized that on one recent evening I did feel slightly funny in my nose, which was such a fleeting feeling that it was possibly nothing at all.

But I always wonder, unfortunately without a definitive answer, what if that evening I did a PCR test on my nose and came up positive. Was I "reinfected"? It is a question to which I do not know the answer to, but it is very important for me and for all people.

My own answer, which is probably not perfect, is that a properly defined reinfection must at least involve symptoms such as fever and viremia and a reasonably low Ct threshold.

This study seems to define reinfection as a "positive PCR test", which always makes me wonder how many of those reinfections were not true illnesses.