A new era of obesity drugs is on the horizon.

New GLP-1 receptor agonists are argued to be stronger, cheaper, and easier to administer than their old counterparts. But what does this mean for the further medicalization of diseases?

Prior posts on Ozempic and other GLP-1 receptor agonists for those interested:

On Tuesday I reported that one of Pfizer’s drugs Lotiglipron developed to treat Type II diabetes/obesity was halted due to safety concerns (the last link above).

In looking at this drug the structure appears far different than other Ozempic-like drugs out on the market.

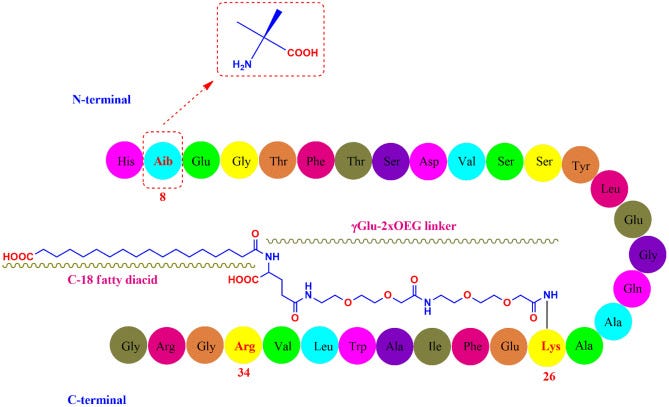

In contrast to prior weight-loss drugs that resemble native GLP-1 or Exendin-4 derived from Gila monsters, these newer drugs are purely synthetic and much smaller in structure.

For instance, the structure of semaglutide is found at the top of the images shown below, with danuglipron on the left and lotiglipron on the right.

This new, synthetic method of GLP-1 receptor agonism appears to be the direction that many pharmaceutical manufacturers are taking, and in some parts it make sense on the part of manufacturers. Note that these new structure are not protein-based, hence they lack the -tide suffix you see for peptides.

Consider that Norvo Nordisk, the developers of semaglutide, have had issues with supplies of their drug for the past several months. Some of these supply issues are likely due to the high demand of the drug, as more celebrities and lay people speak out about their GLP-1 RA use.

Formulation and administration of these drugs have also been a challenge, as many suffer from the first pass effect which reduce their efficacy and bioavailability, and also reduces patient adherence due to the need for routine injections.

Thus, these new, updated drugs are intended to solve these problems due their much smaller sizes and ease of synthesis. Several outlets have already taken to commenting on this new approach, as suggested by the Nature article released just a few days ago:

And Pfizer is not the only company heading in this direction of nonpeptide drug development. Eli Lilly has its own nonpeptide obesity drug undergoing clinical trials1 named Orforglipron:

There have been some debate over the actual nature of appetite suppression and weight-loss caused by the peptide forms of GLP-1 RAs, although it’s believed that the larger size of these molecules may inhibit passage through the blood-brain-barrier, which would allow binding to brain regions and neurons with GLP-1 receptors located on their surface.

So there’s a possibility that these nonpeptide drugs may be far more free to pass into the CNS, and thus may exert a greater appetite suppressing effect, although studies would have to corroborate this hypothesis.

This also raises the question of what effects these newer drugs would have on addiction, as evidence appears to suggest that this class of drugs overall may also reduce the need for alcohol, smoking, or other illicit drugs in those who are prescribed these medications.

It points to an overarching hypothesis that different forms of addiction are likely to be related, but that will be a point for another time.

But as greater interest in these drugs come, so too does the concern over what this would mean for the future landscape of obesity treatment.

Recently, it was reported in Fox Business that doctors who were prescribing Wegovy and other peptide versions of these agonists to patients would have patients forego these treatments, due to the prospect of lifelong use of these medications. It appears that some of these patients have taken to going at it the old-fashioned way through dietary and lifestyle changes rather than having to rely on a drug for the rest of their lives.

That’s all well and good from the perspective that less is better when it comes to pharmaceuticals, but if administration of such drugs become far easier, with far fewer side effects as these new nonpeptide drugs are argued to have, then this position is not likely to hold up in the coming years.

Thus, we are being met with even yet another conundrum, in which the ease of a drug’s use may make it even more desirable for patients, and spur even more incentives for accelerated approval and widespread use of said drugs, and leading to a possible era of weight-loss drug dependency in order to end the obesity epidemic.

Consider that many insurance companies either don’t appear to cover Ozempic-like drugs or have stopped coverage due to the cost or use off-label for weight-loss, as reported in Reuter’s recently. If these nonpeptide versions make it past clinical trials, then it’s likely that these drugs may see coverage by insurance companies if they are indeed far cheaper than their peptide counterparts.

Keep in mind that even as of now, the long-term effects of the currently available iterations of these drugs are still unknown, and so there’s still serious concerns over side effects that can’t be overlooked.

And yet, what would this mean if these drugs do indeed show efficacy in helping reduce addictive behaviors? Would it be beneficial to allow such drugs if they help treat addiction? And wouldn’t obesity and overconsumption of food be categorized as a form of addiction, as there appears to be overlap across different addictions (as I mentioned above?).

There’s a lot to question about the sudden emergence of these drugs and how the public will perceive them in the near future. It begs the question of how much medicalization is actually needed if we are truly entering into an era of widespread weight-loss pill availability.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Pratt, E., Ma, X., Liu, R., Robins, D., Coskun, T., Sloop, K. W., Haupt, A., & Benson, C. (2023). Orforglipron (LY3502970), a novel, oral non-peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist: A Phase 1b, multicentre, blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized, multiple-ascending-dose study in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism, 10.1111/dom.15150. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15150

What does this mean for the further medicalization of diseases? Well, nothing for those that see no use for these things. For the rest, I'm sorry. I know there is demand for injections and pills for what-ails-us. How that demand arises is a study in itself. But wherever it may come from, the saying "as you sow, so shall you reap" still fits.

If we remember the wisdom of Dr. Malcolm, sure we can... but should we? Excluding the very rare compulsive cases that require medical intervention, it seems that whenever we “have a pill for that”, we further alienate ourselves from the responsibility to pursue health, knowledge, and wellness on our own. We also often stop devoting as much time seeking causation.

This allopathic ideology may be better addressed within the field of psychology and sociology, because the same framework is pervasive in many industries. Don’t like mosquitoes? Don’t like weeds? Don’t like your gender? Don’t like remembering phone numbers? Don’t like responsibility or making difficult decisions? We have something for that.

The easy solution is not always the best one for our character, constitution, or communities. Even when faced with the merciful idea of helping severe addiction, isn’t that even simply swapping one crutch for a different one? Perhaps in this case, the magic bullet pill should be retained only for when all other options are thoroughly exhausted, not as a first, designer solution to the inconvenience of responsibility.