Can the Salem Witch Trials be Blamed on a Fungus?

Part II: The Ergot Hypothesis and its Criticisms.

This is a continuation from yesterday’s post. Here, we look at where the ergot hypothesis came from and some arguments against it.

Table of (Relevant) Contents:

The Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials live on (Conclusion)

tl;dr (too long; didn’t read- for those who want the quick pros and cons of the hypothesis)

Many hypotheses have come about in order to explain the events that led to the Salem With Trials and the death of over 20 people.

In the prior post we brought attention to the fungus ergot in particular and how some of the ergot alkaloid compounds have hallucinogenic and convulsive properties which may mimic some of the symptoms of supposed bewitchments experienced by the people of Salem.

But the question still remains; given that no proper explanation was ever provided over the Centuries, what led to the now prominent belief that a fungus is to be blamed for these horrific witch hunts?

Well, like all cultural phenomenon that need to be explained there’s generally one place to look— the Psychology department of a University.

A Battle of the Psychologists

I was confused as to how to properly piece together this information. In the end, it seemed more fitting to summarize different perspectives before providing my own opinions (very loose opinions at that). And so the following information will look at the accounts of different psychologists and whether there is evidence to support or refute the notion that ergot poisoning was responsible for the events leading up to the Salem Witch Trials.

A Hypothesis is Published

The first notion tying ergot to the Salem Witch Trials came from a then psychology graduate student named Linnda R. Caporeal, who published her hypothesis in the number 192 weekly issue of Science published in April 2, 19761.

At the time of its publication it’s likely that hysteria was taken as the main explanation for all of the goings on with witchcraft and the hunting of such beings. Note that such persecutions came about at a time when monotheistic religions gained prominence which contrasted the old, pagan rituals and lifestyles from before.

In essence, the clashing between the two cultures, spurred on by political turmoil and superstitions would justify some of these behaviors (it’s a reason why the term witch hunt has been adopted as a commonly used idiom).

However, Caporael offered a different approach. In her hypothesis she proposed that a physiological explanation could be possible, and even noted that diseases may have been the first route that doctors may have taken before assuming bewitchment:

3) Physiological explanations. The possibility that the girls' behavior had a physiological basis has rarely arisen, although the villagers themselves first proposed physical illness as an explanation. Before accusations of witchcraft began, Parris called in a number of physicians (6, 7). In an early history of the colony, Thomas Hutchinson wrote that "there are a great number of persons who are willing to suppose the accusers to have been under bodily disorders which affected their imagination" (12, vol. 2, p. 47). A modern historian reports a journalist's suggestion that Tituba had been dosing the girls with preparations of jimsonweed, a poisonous plant brought to New England from the West Indies in the early 1600's (8, footnote on p. 284). However, because the Puritans identified no physiological cause, later historians have failed to investigate such a possibility.

Caporael’s hypothesis built off of prior historical evidence of the effects of ergot. However, it is in her own hypothesis in which she makes associations between the consumption of ergot and the symptoms of the young girls in Salem.

For instance, Caporael argues that the timing of rye harvesting lines up with the timing of the symptoms as the threshing and storage of rye may have occurred right before winter, lining up with the first symptoms appearing at the end of 1691:

Spring sowing was the rule; the bitter winters made fall sowing less successful. Seed time for the rye was April and the harvesting took place in August (23). However, the grain was stored in barns and often waited months before being threshed when the weather turned cold. The timing of Salem events fits this cycle. Threshing probably occurred shortly before Thanksgiving, the only holiday the Puritans observed. The children's symptoms appeared in December 1691.

As it relates to weather, Caporael includes an account of the weather during the spring and summer months of 1691, suggesting that the wet and warm months may have been conducive to the growth of ergot. Caporael actually notes that spring sowing was the preferred time, which would raise some doubts to the need for winter susceptibility.

However, note that there’s a bit of uncertainty and ambiguity in Caporael’s writing:

In all probability, the infestation of the 1691 summer rye crop was fairly light; not everyone in the village or even in the same families showed symptoms.

Certain climatic conditions, that is, warm, rainy springs and summers, promote heavier than usual fungus infestation. The pattern of the weather in 1691 and 1692 is apparent from brief comments in Samuel Sewall's diary (24). Early rains and warm weather in the spring progressed to a hot and stormy summer in 1691. There was a drought the next year, 1692, thus no contamination of the grain that year would be expected.

There’s a bit of ambiguity as to the actual weather patterns, including the assumption that infestation may have been “light” in order to account for the select few individuals who had symptoms.

One convincing aspect in Caporael’s hypothesis is an examination of the localization of defenders, accusers, and convicted witches as mapped below:

It’s been suggested that Putnam inherited land from his father west of the divide. Much of this land was swampland, making them areas ripe for ergot takeover if they were used to grow crops.

This may explain why some of the young girls who were experiencing symptoms of bewitchment lie predominately to the west of the divide, as they may have been the most likely to have ingested the tainted rye.

Note that Putnam’s daughter and two other young residents of his estate, as well as Parris’s daughter and niece were some of those afflicted with the “bewitchment” (noted by the X’s on the map).

It makes sense, when paired with political turmoil that those on the side where bewitchment may have occurred would accuse (accusers labeled with A’s) those on the other side of the town of being witches (noted by the W’s and D’s for defenders of the accused), that such a distinct pattern may be realized.

Lastly, Caporael looked at some accounts during the trial in which some symptoms of “bewitchment” were noticed, with some symptoms mimicking that of convulsive ergotism:

The trial records indicate numerous interruptions during the proceedings. Outbursts by the afflicted girls describing the activities of invisible specters and "familiars" (agents of the devil in animal form) in the meeting house were common. The girls were often stricken with violent fits that were attributed to torture by apparitions. The spectral evidence of the trials appears to be the hallucinogenic symptoms and perceptual disturbances accompanying ergotism. The convulsions appear to be epileptiform (6, 13).

Accusations of choking, pinching, pricking with pins, and biting by the specter of the accused formed the standard testimony of the afflicted in almost all the examinations and trials (26). The choking suggests the involvement of the involuntary muscular fibers that is typical of ergot poisoning; the biting, pinching, and pricking may allude to the crawling and tingling sensations under the skin experienced by ergotism victims. Complaints of vomiting and "'bowels almost pulled out" are common in the depositions of the accusers. The physical symptoms of the afflicted and many of the other accusers are those induced by convulsive ergot poisoning.

Caporeal also included the account of one man who lived outside of the town named Joseph Bayler, who after visiting the Putnam’s experienced feelings of sudden blows to his stomach followed by feelings of pins and needles in his extremities later on:

Joseph Bayley lived out of town in Newbury. According to Upham (4), the Bayleys, en route to Boston, probably spent the night at the Thomas Putnam residence. As the Bayleys left the village, they passed the Proctor house and Joseph reported receiving a "very hard blow" on the chest, but no one was near him. He saw the Proctors, who were imprisoned in Boston at the time, but his wife told him that she saw only a "little maid." He received another blow on the chest, so strong that he dismounted from his horse and subsequently saw a woman coming toward him. His wife told him she saw nothing. When he mounted his horse again, he saw only a cow where he had seen the woman. The rest of Bayley's trip was uneventful, but when he returned home, he was "pinched and nipped by something invisible for some time" (11). It is a moot point, of course, what or how much Bayley ate at the Putnams', or that he even really stayed there. Nevertheless, the testimony suggests ergot.

Overall, Caporael suggests that other factors could have been instrumental in the symptomatology, as it is likely that the ergot poisoning may have caused some of the symptoms which were then exacerbated by notions and superstitions surrounding witchcraft:

While the fact of perceptual distortions may have been generated by ergotism, other psychological and sociological factors are not thereby rendered irrelevant; rather, these factors gave substance and meaning to the symptoms. The content of hallucinations and other perceptual disturbances would have been greatly influenced by the state of mind, mood, and expectations of the individual (30). Prior to the witch cake episode, there is no clue as to the nature of the girls' hallucinations. Afterward, however, a delusional system, based on witchcraft, was generated to explain the content of the sensory data (31, p. 137).

And so Caporael’s hypothesis spurred the association between ergot and the Salem Witch Trials. Many of these accounts sound convincing— tales of hallucinations and visions of specters certainly would evoke thoughts of witchcraft.

Her work has been cited by many people even to this day.

Ironically, I will also state that I first heard of the ergot hypothesis in one of my Psychology courses. Let’s just say I have some of my personal biases with this hypothesis.2

However, there are several questions raised in regards to Caporael’s hypothesis, and just like the notions of witchcraft some of these ideas may not be substantiated.

A Rebuttal against Ergot

Even at the time Caporael’s ideas were met with a good deal of skepticism and wasn’t readily adopted as a plausible hypothesis among historians.

A few years after her piece two psychologists, Nicholas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb, would jointly publish a paper in 19763 refuting the hypothesis raised by Caporael in a not so subtle way.

In their piece they criticized much of the accounts provided by Caporael by scouring through the available testimonies.

In many cases, the symptoms of convulsive ergotism tend to not appear as widely as one would assume. Keeping in mind that ergot poisoning should present with various symptoms the accounts and testimonies of the villagers paint a different story to the contrary.

For example, symptoms of convulsive ergotism generally include diarrhea and other gastrointestinal ailments. Although Caporael makes mention of some of the young girls having such symptoms, the actual testimonies don’t appear to indicate that this symptom was widespread:

Caporael says that "complaints of vomiting and 'bowels almost pulled out' are common in the depositions of the accusers" (1, p. 25). This statement is incorrect. Records of Salem Witchcraft (RSW) (11) contains 117 depositions by the afflicted girls and 79 depositions in which other witnesses describe the behavior of the girls. There are also eyewitness accounts by Mather (10), Lawson (9), Brattle (7), and Hale (8) which are not contained in RSW. We examined all these sources and were unable to find any reference to the occurrence of vomiting or diarrhea among the afflicted girls. In all these sources we found only three instances of gastrointestinal complaints among the girls (11, vol. 1, p. 106; vol. 2, p. 31). In one of these cases (11, vol. 1, p. 106) the girl making the complaint (Mary Warren) lived outside the area that Caporael suggested was exposed to ergot (13). Thus 8 of the afflicted girls did not report any gastrointestinal symptoms. Those who did reported only a single instance. None of them reported vomiting or was observed to vomit, and there is no indication that any of them suffered from diarrhea.

A lack of this symptom alone doesn’t discredit ergot poisoning. However, one strange symptom that has been mentioned several times is the appearance of specters or of witches visiting people assumed to have been afflicted with bewitchment.

Now, I have never taken LSD so I have no personal account as to what visions are typical with LSD. However, some research suggests that LSD may lead to hallucinations through visual distortions, but they shouldn’t present with seeing apparitions or other figures (unlike the machine elves associated with DMT use).

Given that Caporael has associated the hallucinations of the young girls to some of these LSD derivatives found in ergot, it raises questions as the use of these compounds should not evoke apparitions or other images.

This is another criticism brought forth by Spanos and Gottlieb:

Caporael points out that one ergot alkaloid, isoergine (lysergic acid amide), has 10 percent of the activity of LSD and might therefore produce perceptual disturbances. She remarks that "the spectral evidence of the trials appears to be hallucinogenic symptoms and perceptual disturbances accompanying ergotism" (11, p. 25). The term "hallucination" is, unfortunately, very unspecific, and in the psychological literature is used to refer to a wide variety of distinct experiences (16). Although LSD is commonly referred to as a hallucinogen, Barber has correctly pointed out that "subjects who have ingested [LSD] very rarely report, when their eyes are open, that they perceive formed persons or objects which they believe are actually out there" (17, p. 109). Instead, they tend to report perceptual distortions such as persistent afterimages, rainbow-like colors, halos on the edges of objects, changes in depth perception, contours that appear to undulate, and the like. None of the testimony given by the afflicted girls indicates perceptual distortions of that kind. Instead, they reported seeing "formed persons"-the specters of the accused attacking, biting, pinching, and choking them and others.

This raises questions as to where these apparitions may have come from. Remember that several of these accounts tell of the appearance of what seems to be witches. It would be rather strange for these individuals to have seen images of witches unless brought forth by preconceived notions that may influence perception.

One example includes a refutation of Joseph Bayler’s story. Caporael’s account doesn’t provide much convincing evidence in support of bewitchment, and the reports from Spanos and Gottlieb add to this criticism (emphasis mine):

The final case, and the only one to exhibit as many as four of the symptoms listed in Table 1, is that of J. Bayley, who as Caporael points out did not live in Salem Village. He and his wife had spent one evening there and left the next day. On their way out of the village they passed the house of a man and wife accused of witchcraft. Bayley reported that at this point he felt a blow to his chest and a pain in his stomach. He also thought he saw the accused witches (who were jailed at the time) near the house and then became speechless for a brief period of time. Shortly thereafter he experienced another blow to the chest and thought he saw a woman in the distance. When he looked again he saw a cow rather than a woman. After arriving at his home he reported feeling pinched and bitten by something invisible. His wife experienced no symptoms. Caporael says Bayley's testimony "suggests ergot" (1, p. 25). It seems far more plausible, however, that being a fervent believer in witchcraft he experienced an upsurge of anxiety as he approached the house of two convicted witches than that he ingested ergot during his stay in the village and by coincidence experienced the first symptoms of his poisoning as he happened to pass the witches' house.

Both accounts don’t explain much in the ways of how Joseph Bayley became ill while his wife was spared, and it doesn’t quite explain how spending such short time in the village could elicit such symptoms as young girls are more susceptible to ergot poisoning and the effects require continuous exposure and consumption of ergot.

Overall, it’s hard to argue that such limited evidence could be indicative of compulsive ergotism given the small level of exposure.

In fact, in examining the symptoms of various villagers who witnessed bewitchment a pattern can be seen, in that a majority of the symptoms appear to revolve around apparitions and convulsions specifically.

Again, one would assume that ingestion of ergot would lead to multiple symptoms rather than these two symptoms in particular.

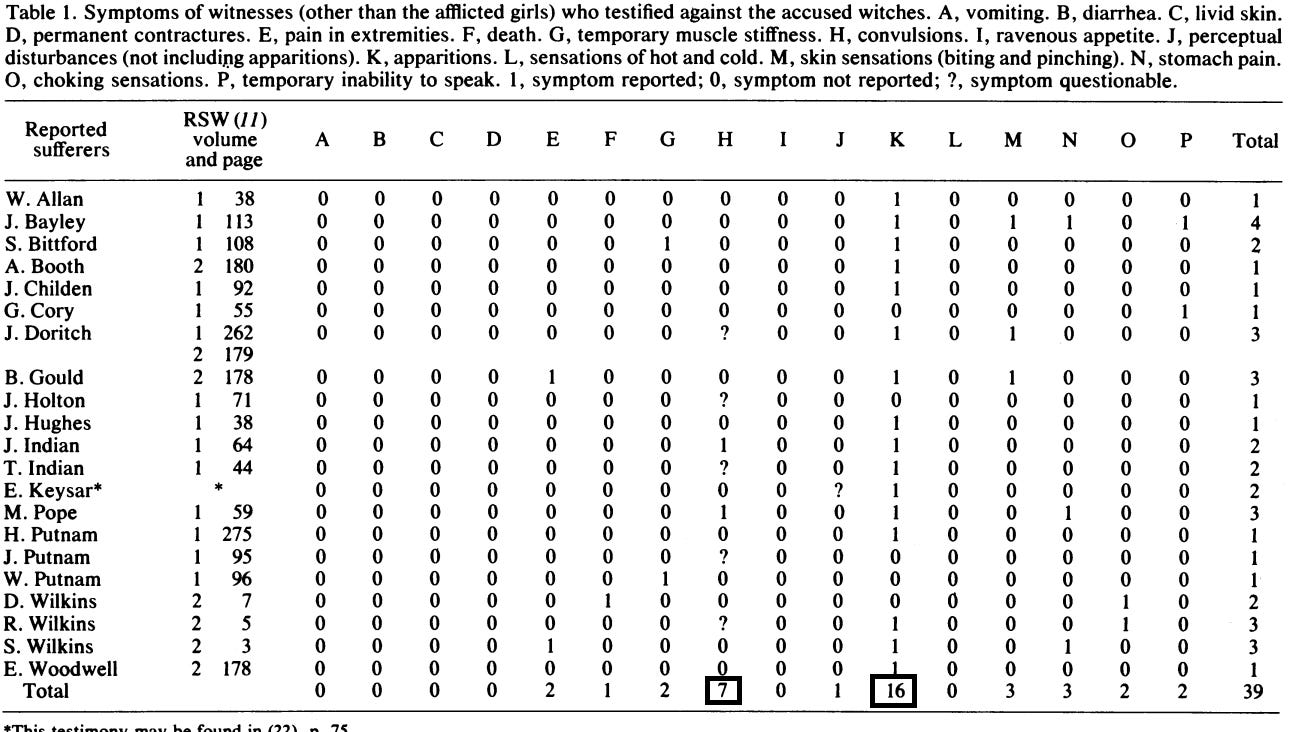

In reviewing some of the other villagers’ symptoms Spanos and Gottlieb provide the following chart:

Note that when you look at each row (which relates to a witness or subject of “bewitchment”) that most people appear to have reported only one symptom (J. Bayley being considered to have had at least 4 symptoms; the most out of recorded witnesses).

Even barring that the timelines of these experiences don’t coincide with suggested ergot exposure, the fact that such experiences tend to revolve around apparitions-which would run counter to the actual experiences of those who suffer ergotism or ingest LSD derivatives- again raises some doubts as to the role of ergot in lieu of other possibilities.

Instead, Spanos and Gottlieb suggest that many of these symptoms may have been psychological in nature, almost akin to a social contagion. They argue that the young girls may have taken the social cues of those around them and acted accordingly. It would make sense given that symptoms of ergotism shouldn’t appear when prompted, so to speak (emphasis mine):

According to Caporael, the afflicted girls' convulsions "appear to be epileptiform" and their reports of being bitten, pinched, and pricked by specters "may allude to the crawling and tingling sensations under the skin experienced by ergotism victims" (1, p. 25). There is no question that the girls frequently convulsed and reported being bitten and pinched. However, a careful look at the social context in which these symptoms were typically manifested belies the notion that they resulted from an internal disease process. The trial testimony indicates very clearly that the girls convulsed and reported being bitten and pinched when an accused person's behavior provided them with a social cue for such acts.

For example, when one of the accused was ordered to look at an afflicted girl, "he looked back and knocked down all (or most) of the afflicted who stood behind him" (11, vol 2, p. 109). In another case, "As soon as she [the accused witch] came near all [the afflicted] fell into fits" (11, vol. 1, p. 140). The courtroom testimony contains a great many instances of the afflicted girls' convulsing en masse when the accused entered the room, looked in their direction, moved his chair, and so on (11). The afflicted girls' reports of being pinched, choked, and bitten are described thus by Lawson, an eyewitness (9, p. 156):

It was observed several times, that if she [the accused witch] did but bite her underlip in time of examination the persons afflicted were bitten on their arms and wrists and produced the marks before the magistrates, Ministers and others.

The afflicted also produced the pins with which the accused purportedly pinched them (9, p. 156).

The afflicted girls were responsive to social cues from each other as well as from the accused and were therefore able to predict the occurrence of each other's fits. In such cases one of the girls would cry out that she saw the specter of an accused witch about to attack another of the afflicted. The other girl would then immediately fall into a fit (1, vol. 1, p. 183). Termination of the girls' convulsions was also cued by social-psychological factors.

At this point it’s important to remind readers that all of these accounts are secondhand and nearly 300 years after the fact, so some skepticism should be warranted when retelling the accounts of these witnesses.

At the same time many of these villagers would not be aware of the level of psychological/physiological knowledge that many of us have now, and so we may argue that villagers who would knowingly lie would lie in favor of what they believed to be the type of symptoms that should be associated with bewitchment.

It’s for this fact that there’s a good possibility that such experiences could be influenced by beliefs and assumptions at the time, possibly ramped up by social contagion and the fears over the supernatural.

What started as benign may have been blamed on the supernatural, creating an unnecessary feedback loop in which the girls would eventually take on the clear symptoms of bewitchment:

It is worth noting that the initial symptoms of the afflicted girls were rather ambiguous, and that they began to correspond more closely to popular stereotypes of demonic behavior as the girls gained increasing exposure to information about those stereotypes. The initial symptoms included "getting into holes, and creeping under chairs and stools, and [using] sundry odd postures and antic gestures, uttering foolish and ridiculous speeches" (20, p. 342). About 2 weeks after these symptoms began a neighbor had a "witch cake" baked in order to determine whether the girls were bewitched. Only after this event did the girls begin convulsing and reporting the specters of witches (20, p. 342). As the witchcraft trials progressed, the girls added to the repertoire. They collapsed en masse when looked at by the accused during the first trial (11, vol. 1, p. 18). During the fourth examination they began complaining of being bitten whenever they observed the accused nervously bite her lip and of being pinched when she moved her hand (14, vol. 2, p. 48). In later examinations they began to mimic the accused; they held their heads in the same position as that of the accused (11, vol. 1, p. 87) and rolled their eyes up after the accused did so (11, vol. 1, p. 142). This temporal pattern suggests that the demonic manifestations were learned, that the girls' behavior was gradually (although perhaps unwittingly) shaped to fit the expectations for demonic behavior held by the community.

The refutation proposed by Spanos and Gottlieb cast some considerable doubt over the idea that ergot played as a big of a role as one would assume. The evidence, I would argue, is rather spurious and may better fit the idea of finding evidence rather than examining the phenomenon as a whole.

Now, to be fair to Carporael her perspective was rather hesitant and considered that multiple factors are likely to be at play.

I would also raise some criticisms against Spanos and Gottlieb, as they don’t provide proper distinctions between convulsive or gangrenous ergot. Note that some of the symptoms overlap, such as the feelings in the extremities of the bodies, although gangrenous ergotism should present with severe burning sensations and skin discolorations that should not be seen in convulsive ergot victims.

Their writings suggest that the lack of gangrenous ergotism symptoms would refute the notion that ergot played a role, however once again convulsive ergotism shouldn’t present with signs of gangrene.

Most ergot poisoning victims don’t present with both, and so it’s an argument that would not be substantiated by the literature.

They also comment that many of these symptoms would be alleviated by the dairy and seafood that the villagers were likely to have eaten— sources of Vitamin A which have been argued to attenuate much of the symptoms of ergotism.

There doesn’t appear to be any evidence in support of an association between ergotism and hypovitaminosis, and instead an argument could probably be made that Vitamin A may be the reason why the symptoms of ergot poisoning were not so widespread- if they are to be believed.

The Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials live on

Over the next few years more writings would come out in defense or in further refutation in regards to the ergot hypothesis.

In 1982 a historian and associate professor Mary K. Matossian would come out with her own piece in defense of Carporael’s work4, with one note that the cold winters followed by damp springs would create for an environment fit for ergot- an argument that would, ironically, run counter to Carporael’s suggestion that spring was the heavily favored sowing season for the villagers.

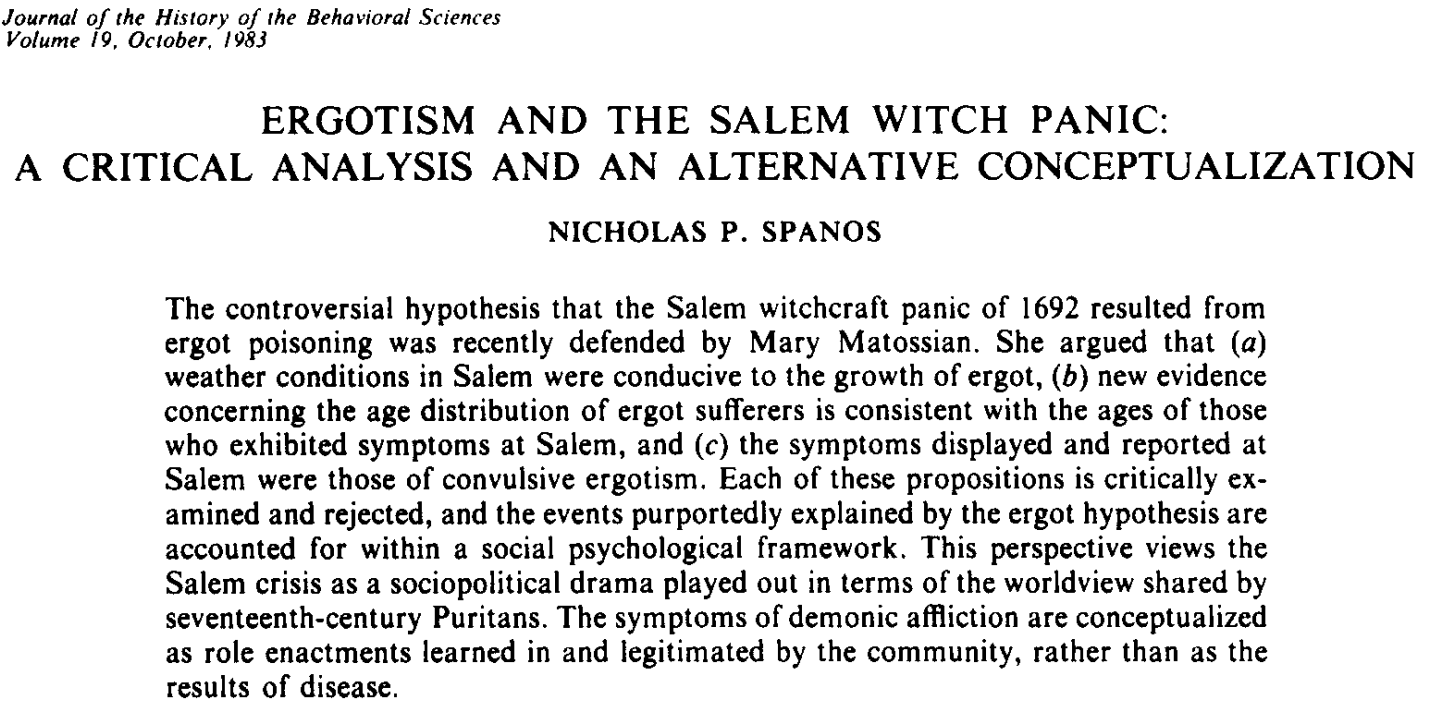

Spanos was quick to rebut with his own, lengthy article pointing to psychosocial factors being the main culprit5.

The criticisms against the ergot hypothesis would eventually include a pediatrician named Alan Woolf who released his own piece in 20006:

Alan Woolf’s brief review is great for the fact that he provides a tl;dr (too long; didn’t read) summary of the pros and cons of the ergot argument (I will provide a link for those who want a quick summary).

tl;dr

And so just like all other topics the idea as to whether ergot played a role in the Salem Witch Trials continues to be divisive. Even with such spurious evidence it’s interesting that such an idea continues to live one.

I would argue part of this reason lies in reporting, as this report from Historic Mysteries leans into the fact that there is a good deal of evidence in support of the hypothesis. After Matossian released her piece the New York Times released a favorable article supporting the hypothesis even further.

Although the Salem Witch Trials is heavily referenced for its historical significance, it’s generally through cultural/media portrayal that we tend to remember that such an incident occurred, with a noteworthy example being the film Hocus Pocus. It’s even been suggested that many tourists visit Salem, Massachusetts because of the film rather than the actual history, although I would also consider this to likely be hearsay to deter rampant, rowdy tourism during this time of the year.

Another likely reason would be the alluring aspect of having an answer. In a world that seeks and requires explanations, having a reason for such a horrific incident may be provide some clarity.

Strangely, we may also seek to find answers that may take away some of the blame from ourselves. If we are to believe that we are not capable of such inhumane atrocities, that we became bewitched or were influenced by external factors, then we may justify our actions irrespective of how inhumane they are— it was not our fault; I was not in control. I was afraid and acted accordingly.7

There’s a reason why the term with hunt perseveres even to this day. It serves as an important reminder that divisiveness continues in all aspects of our lives, and that we should not be quick to make assumptions based on spurious accusations that have not been substantiated.

In summary, we may never find out the true explanation for what led to the persecution and death of over 20 innocent people. Although the ergot hypothesis could be considered rather spurious, the greatest possibility could be a collection of multiple factors.

And already divided town, full of superstitious, God-fearing villagers would only need a tinge of ergot to get things started.

During this time of the year, it’s a reminder of the atrocities that have been committed, and the atrocities that we are all capable of.

And sometimes that can be the most frightful thing of all.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Caporael L. R. (1976). Ergotism: the satan loosed in Salem?. Science (New York, N.Y.), 192(4234), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.769159

As I mentioned before I double-majored in Biochemistry and Psychology during my undergrad. Balancing the classes was difficult, and for some reason in one semester I decided to put one of my psychology courses after one of my lab classes. I would eventually regret this decision and I essentially stopped showing up to the class and reading the textbook on my own time.

Now, the professor was aware that people would not show up, and near the end of class rather than teach about psychology topics he showed several videos on the Salem Witch Trials. In fact, to sort of punish those of us who didn’t show up he made the final based predominately on these videos, with some questions asking about ergot and contaminated rye bread.

Let’s just say that I needed at least a D on this final to keep my A in the class. This was the only psychology class I received a B in, and I still remember it to this day…

Spanos, N. P., & Gottlieb, J. (1976). Ergotism and the Salem Village witch trials. Science (New York, N.Y.), 194(4272), 1390–1394. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.795029

Matossian, M. K. (1982). Views: Ergot and the Salem Witchcraft Affair: An outbreak of a type of food poisoning known as convulsive ergotism may have led to the 1692 accusations of witchcraft. American Scientist, 70(4), 355–357. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27851542

Spanos N. P. (1983). Ergotism and the Salem witch panic: a critical analysis and an alternative conceptualization. Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences, 19(4), 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696(198310)19:4<358::aid-jhbs2300190405>3.0.co;2-g

Woolf A. (2000). Witchcraft or mycotoxin? The Salem witch trials. Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology, 38(4), 457–460. https://doi.org/10.1081/clt-100100958

Very good compare/contrast of the available evidence. Sometimes things that may seem plausible on one hand don’t seem so relative on the other. Overall this is a great example of how I prefer to research things - by examining both sides of the story. I find that oftentimes the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

Might Puritanism have been a cause of witch hunts?