Can the Salem Witch Trials be Blamed on a Fungus?

Part I: An introduction and a look at Ergot.

Witchcraft has had a long, sordid history across many cultures, especially for those in Europe. As monotheistic religions grew and came into conflict with pagan or holistic practices it was not uncommon to see trials and the targeting of individuals for practicing things that were not deemed socially or religiously fit.

Such witch hunts spanned several centuries in Europe and made its way over to the Americas, with one of the most recognizable events occurring in a small village called Salem, Massachusetts.

When one looks for clear examples of injustice and undue process, one has to look no further than the Salem Witch Trials, as it serves as prime example for how spurious accusations and superstitious beliefs can lead to unneeded death and divisiveness.

The accusations of bewitchment came about at a time of great unrest for the small farming village, as there was hostile rivalry between two families— the Portners and the Putnams.

The story leading to the eventual start of the Salem Witch Trials suggests that a merchant turned pastor Samuel Parris arrived to the small town of Salem bringing with him his wife, three children, and two slaves from Barbados.

One of these slaves, Tituba, would tell stories about voodoo practices to some of the children, including Parris’ daughter Betty and his niece Abbigail.

Eventually, both Betty and Abbigail would show with strange behaviors and symptoms that worried those around them.

Britannica explains it as follows:

In January 1692 Betty’s and Abigail’s increasingly strange behaviour (described by at least one historian as juvenile deliquency) came to include fits. They screamed, made odd sounds, threw things, contorted their bodies, and complained of biting and pinching sensations.

After no explanation could be provided the local doctor, William Griggs, blamed such symptoms on supernatural forces, most notably the work of witches and witchcraft, thus setting the stage for the eventual witch trials which would culminate in the unjust hangings and deaths of several people.

A deeper dive into the witch trials can be found on Britannica’s website, but for our sake the question remains: what exactly were the cause of the symptoms displayed by Betty and Abigail, which later came about in other children and young women?

What were these symptoms of bewitchment that led to the accusations that witches were afoot?

Several hypotheses have come about, including various mental disorders and other diseases that may have presented as hallucinations or convulsions, including psychosis or epilepsy.

However, one prominent hypothesis that tends to make its rounds points to contaminated food sources as being the main cause of these bewitchments. It’s been argued- and supported/refuted by several researchers- that the psychological and physiological symptoms displayed by the young girls in Salem may have been caused by ergot poisoning stemming from the fungus ergot which can contaminate rye and rye-based flour.

We’ll explore this hypothesis and see whether all of this could be explained by fungal poisoning, or if there’s a bit more here than just a bit of fungus.

Ergot-nomics: An Overview into Ergots

Ergots are a class of fungi from the genus Claviceps, with many members parasitizing various grain and cereal species.

The most common ergot is the Claviceps purpurea, which infects rye. Common features of parasitized rye is the presence of the sclerotium, which is a large black fruiting body from the ergot that protrudes from the rye plant.

The spread of ergot tends to require two conditions: a harsh, cold winder followed by a damp spring.

It’s suggested that stalks of rye become weakened over harsh winters making them more susceptible to invasion by ergot. A damp spring also creates the proper environment for fungal growth, and so pairing of the two allows for the ergot spores to take hold and parasitize the plant.

Ergot Poisoning & Ergotism

There have been many historical accounts of ergot poisoning spanning several millennia, with some accounts across many cultures discussing hallucinations after consumption, or descriptions of the strange growths from plants akin to ergot parasitism.1

Ergot poisoning is derived from the excess ingestion of compounds found in ergot sclerotium called ergot alkaloids.

Ergot alkaloids comprise some of the widest arrays of nitrogenous-based fungal metabolites in nature. Although ergot alkaloids have many toxic side effects they have been used extensively in many cultures as a therapeutic agent.2 In modern times, some of these ergot alkaloids are being looked at as possible therapeutic agents for Parkinson's disease.

Ingestion of large quantities of ergot alkaloids from contaminated foods may lead to the disease known as ergotism. Historical accounts suggest that epidemics of ergotism have occurred over the centuries (Eadie, M. J.3):

There are many reports of ergotism outbreaks in the literature from medieval and early modern times. Outbreaks may also have occurred in ancient times.6 In his Traité des Nerfs et de Leurs Maladies (published in 1778–1780), Tissot1 reviewed the recorded outbreaks of ergotism in central and western Europe. The record of epidemic ergotism in Europe was tabulated by Hirsch in 1885,2 and the subject was discussed in Barger’s monograph Ergot and Ergotism4 in 1931, when epidemic ergotism had nearly disappeared.

Interestingly, the presentation of ergotism is bifurcated and can be categorized as either “gangrenous” ergotism or “convulsive” ergotism based on the symptoms that manifest.

Gangrenous ergotism, also known as St. Anthony’s Fire, is typified by the discoloration and pain in the extremities, which may lead to gangrene and sepsis of limbs. In contrast, convulsive ergotism tends to present with hallucinations and convulsions.

A description of both forms of ergotism comes from a review by Schiff, P. L.:

The first gangrenous form (Ergotismus gangraenosus), commonly known as “holy fire,” “infernal fire,” or “St. Anthony's Fire,” was more common in France and its effects were characterized by pronounced peripheral vasoconstriction of the extremities (limbs). Hands, feet, and whole limbs would swell, producing a violent, burning pain that ultimately culminated in the separation of a dry gangrenous limb (usually a foot) at a joint, without pain or loss of blood. St. Anthony's Fire was so named because the Order of St. Anthony traditionally cared for sufferers in the Middle Ages, and the condition was characterized by severe burning pain (“fire”). The second form of ergotism, also known as the convulsive form (Ergotismus convulsivus), was particularly common in Germany and was typically characterized by the development of delirium and hallucinations, accompanied by rigid, extremely painful flexed limbs, muscle spasms, convulsions, and severe diarrhea.

Strangely, both forms of ergotism can be derived from the same ergot strain (eg. Claviceps purpurea), and in most cases one who presents with some form of ergotism does not present with the other.

One clear example is a divide between the east and west regions of the Rhine River4, where countries to the west such as France experienced predominately gangrenous ergotism while those to the east such as Germany experienced predominately convulsive ergotism.

It’s assumed that this distinction between convulsive and gangrenous ergot stems from different ergot alkaloid content produced by the fungus, which may depend upon climate and nutrient sources.

When it comes to gangrenous ergotism, it’s believed that many of the effects stem from peptide ergot alkaloids such as Ergotamine which act as strong vasoconstrictors, leading to its use in the early 20th Century as a treatment for migraines and uterine contractions.5

However, use of such compounds may lead to vasospasms (persistent contraction of blood vessels which may cut off blood flow). Severe cutoff of blood and circulation through prolonged vasoconstriction is likely the explanation for the skin discoloration and eventual gangrene seen in individuals who consumed contaminated rye products.

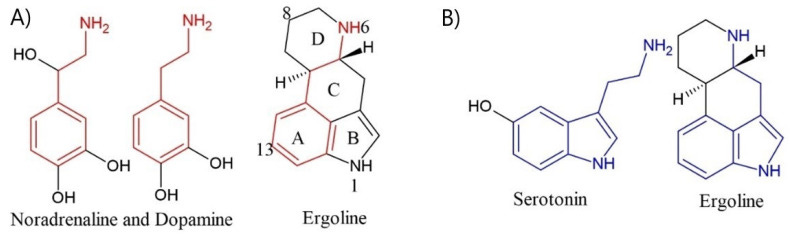

Convulsive ergotism may stem from Lysergic acid derivatives which mimic the structure of Catecholamines due to their Ergoline backbone.

Of course, Lysergic Acid serves as a precursor for Lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD, and research into LSD stemmed from synthesis of different lysergic acid derivatives.6

As such, these compounds readily bind to 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine, or more commonly known as Serotonin) receptors and may create hallucinations and other psychotropic responses (Schiff, P. L.).

LSD and related hallucinogens are known to interact with brain 5-HT receptors to produce agonist or partial antagonist effects on serotonin activity. This includes both the presynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors, as well as the postsynaptic 5-HT2 receptors. Theoretically, LSD and other hallucinogens promote glutamate release in thalamocortical terminals, thus producing a dissociation between sensory relay centers and cortical output. It is not known whether the agonist property of these hallucinogens at 5-HT2C receptors contributes to behavioral alterations. LSD has also been demonstrated to interact with many other 5-HT receptors, including cloned receptors whose functions have not yet been determined. In any event, the precise mechanism by which hallucinogens exert their effects remains unsolved.

It’s been suggested that convulsive ergotism symptoms are similar to that of serotonin syndrome (Eadie, M. J.).

However, this effect is also shared by Ergotamine and other ergot peptides, as many of them share the lysergic acid moiety, allowing them to bind to these receptors as well.7

This makes the situation all the more confusing, as both forms of ergotism are likely to be derived from vasospasms caused by ergot alkaloids, and yet the symptoms are unique and tend not to occur together.

It’s likely that differences in growing seasons and nutrients may alter the level of ergot peptide derivatives relative to lysergic acid derivatives (and vice versa), and it’s the net agonist/antagonistic effects based on the overall sum of ergot alkaloids that determines whether the side effects are convulsive or gangrenous in nature.

Also, note that many of actual effects of specific ergot alkaloids have not been intrinsically tied to specific ergotism. It’s only through isolation and synthesis of specific compounds that we know that one alkaloid may be tied to one form of ergotism.

For instance, the therapeutic use of Ergotamine Tartrate for migraines tends to present with symptoms of gangrenous ergotism in people who take excess8, pointing to this compound in particular as a possible agent in the disease.

Fortunately, modern practices have been able to remove ergot and other contaminates through the manufacturing process, and rarely does anyone in the modern world suffer from ergot poisoning through consumption of rye or other cereals.

However, the same can’t be said for those in centuries past, and for the girls in Salem Massachusetts ergot poisoning could have been a reality for the symptoms that they presented with.

Or maybe not.

The next section will take a look at where the idea of tying ergot poisoning to the Salem Witch Trials came from, including refutations of such a hypothesis.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Schiff P. L. (2006). Ergot and its alkaloids. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 70(5), 98. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj700598

One example is the use of ergot in Europe to help increase uterine contractions and speed up labor (oxytocic effects), although the side effects of ergot may also result in stillbirth showing a dangerous duality with these compounds.

Additional toxicity can be found in this brief review from Smakosz, et al.:

Smakosz, A., Kurzyna, W., Rudko, M., & Dąsal, M. (2021). The Usage of Ergot (Claviceps purpurea (fr.) Tul.) in Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Historical Perspective. Toxins, 13(7), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13070492

Eadie M. J. (2003). Convulsive ergotism: epidemics of the serotonin syndrome?. The Lancet. Neurology, 2(7), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00439-3

Use of Ergotamine (in the form of Ergotamine Tartrate) has fallen to the wayside over the years, and possibly for the best as the most bioavailable form of the drug came in the form of rectal suppositories.

Schiff, P. L. provides a pretty in-depth explanation for Dr. Hoffman’s discovery and use of LSD. It’s very long but it’s a pretty interesting story:

Lysergic acid diethylamide (German term: lysergsaurediethylamid) was first synthesized in 1938 in a screening of compounds for oxytocic activity and was the 25th semisynthetic ergot that Dr. Albert Hofmann of Sandoz AG in Basel, Switzerland, prepared by combining (+)-lysergic acid with different amines. The compound was tested in comparison with ergonovine and found to have less oxytocic activity and thus Sandoz pharmacologists ceased any further development of this particular formulation. According to company policy, LSD-25 should thereafter have been discounted and never resynthesized. However, on Friday, April 16, 1943, Dr. Hofmann, acting under a “peculiar presentiment” that the compound possessed as yet undiscovered properties, resynthesized the compound. He was interested in further investigating the analeptic activity of LSD-25 in comparison to nikethamide because of the partial structural similarities of the 2 compounds. Unknown to him, Hofmann accidentally ingested some of the product during the purification and crystallization of lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate, and was compelled to go home in midafternoon and lay down. He experienced a dazed and dream-like state, in which he sensed a distortion of time and was flooded with vivid, highly colored, kaleidoscopic images of extreme plasticity and unusual dimension. Several hours later he returned to normal and inherently understanding that these reactions had to be a result of something that he had come in contact with in the laboratory, was prompted to undertake a series of self-experiments ingesting the smallest quantity of an ergot alkaloid (0.25 mg) that at the time might be expected to produce a biological effect. On Monday, April 19, he separately ingested every product (in a dosage of 0.25 mg) with which he had worked the previous Friday. About 40 minutes after ingesting a solution of lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate the hallucinations and emotions that he had previously experienced returned. He spoke and wrote only with difficulty, and requested that his laboratory assistant accompany him home. As they rode their bicycles to his home (no automobiles used during WWII, except for designated individuals), Hoffmann's field of vision alternately wavered and became distorted, and he had the sensation of not being able to move from place to place, even though his assistant later confirmed that they had traveled rapidly. On arriving home, he asked his assistant to call for the family physician and also requested milk from his neighbors. He recovered in about 14 hours and his colleagues at Sandoz were astounded at his description of the event. A few of them ingested small doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and confirmed Hofmann's description and experience. Since it is currently believed that marked behavioral changes occur in dosages of 25-50 nanograms (ng = 10−9 g), it can be estimated that Hofmann ingested roughly a 10,000-fold overdose of the hallucinogen. This unique man, who made such a staggering discovery in his seminal research with LSD, just recently reached his 100th birthday. Sandoz tried to find a therapeutic, commercial utility for LSD, even providing free samples and financial support to many investigators, but ultimately researchers observed that the experiences of a numerous variety of patients (psychiatric, alcoholic, cancer, and others) included as many adverse reactions (“bad trips”) as beneficial ones.

Merhoff, G. C., & Porter, J. M. (1974). Ergot intoxication: historical review and description of unusual clinical manifestations. Annals of surgery, 180(5), 773–779. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-197411000-00011

Well, the bewitching could be attributed to ergot. Lots of evidence it. But the witch trials can be attributed to sociopathic preachers, politicians, and manipulated fear. Sound familiar?

I am reminded of Michael Shermer's book: Why People Believe Weird Things, which covers witch trials from the middle ages, Salem, holocaust deniers etc. Seems like an updated version could include people believe the government narrative about (I was going to say covid and the v@x), well, just about everything.

You deserve a dedicated channel, yet another great article. Thank you. ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐