Why is this language appearing in science journals?

Gender ideology is seeping into science.

Apologies for anyone waiting for an assessment of Barmada, et al.’s hypothesis with respect to myo/pericarditis incidences in post-vaccinated individuals. As I mentioned on Friday the study is extremely dense in technical language, and not much is provided in the form of elaboration. Because of that, I found that trying to cover the article led me to having to define and elaborate on the information provided by the authors. This just led to far too dense of an assessment, although I can’t a way around it without leaving readers with the idea of “listen and believe” that I’m not a big fan of.

Anyways, usually when I get stuck in reading an article I just shift my attention elsewhere and see what else is going on.

As of now a recent article published in JAMA1 seems to argue that they have better defined Long COVID/PASC, as the current diagnostic criteria is far too broad and really cannot differentiate between real PASC and noise:

I may cover this while I try to grapple with Barmada, et al. a bit further.

However, this post isn’t about an initial assessment of Thaweethai, et al.’s study, but more about the language used in the article.

There’s an ongoing debate about the use of “gendered” language culturally/socially with respect to pronoun usage and other ideological sticking points. Most of these arguments have stayed within the realms of cultural discourse. However, over the years this sort of language has begun to creep into science, with several recent publications even taking to adopting this language in the publications of their articles.

For instance, the above JAMA piece uses the phrase “sex assigned at birth” within their demographic breakdown:

In contrast to other people on the COVID critical side of the discourse, I don’t have any qualms with someone being trans so long as they do not enforce their ideology onto young people, and really the rest of society. If they live to wish as they see fit without targeting others I don’t see a problem with that.

However, that’s not the point of highlighting this language. My gripe with this language is the use of the word assigned, as if to say that the designation of one’s sex is based upon a doctor’s subjective ruling rather than the objective makeup of one’s sex chromosomes or anatomy.

Now, a point can be made that the use of this language may be done to include intersex individuals, but I don’t see how that would require the inclusion of the word “assign”, as an intersex individual would, by all accounts, be determined by anatomically different sex organs and chromosomal makeup. Again, it’s not as if the assignment would be based upon subjectivity.

But the main issue with this language seeping into science articles is that it overlooks the fact that there are inherent, objective differences between sexes that need to be considered within the context of public health.

A trans woman will still be at risk of developing prostate cancer, and the trans man proclaiming that “men can have periods” would still be at risk of ovarian/uterine cancer as well as polycystic ovary syndrome. Such diseases cannot be overlooked by conflating gender and sex, while also overlooking the fact that these risks of cancer may be inherent to an individual’s chromosomal, and innate biological makeup.

Take the fact that people are still trying to figure out why young males are more inclined to be at risk of vaccine-related myo/pericarditis relative to females. One may argue that this bias may be driven by sex and age-related immune differences, in which young males may be more inclined towards an innate immune response compared to other groups, and this may explain some of these reports of heart inflammation.

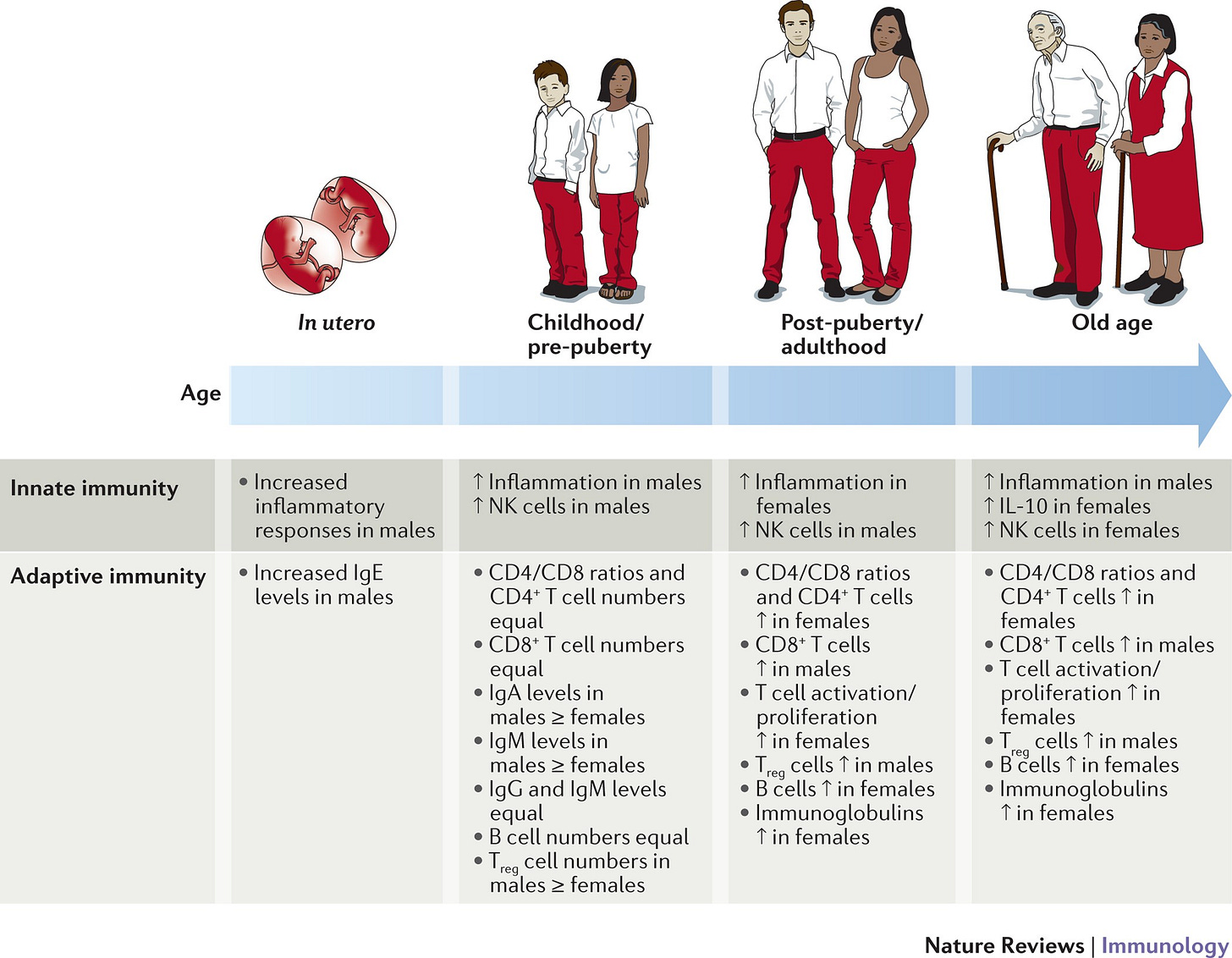

When trying to look up information on sex differences in immunity in order to corroborate this assumption, I came across this review in Nature2:

The review is rather interesting, and I haven’t gotten through all of it yet. However, from what I can glean there’s apparent differences in both innate and adaptive immune responses with respect to males and females, with some of these differences being derived from differences in sex chromosomes.

An overview can be seen in the diagram below with respect to immune differences across ages and sex:

This is due, in part, to several immune-related genes being found on the Y chromosome, with a large portion of other genes being found on the X chromosome, and thus may suggest a directed difference in immune responses between sexes.

Because males only carry one X chromosome, any mutation that confers reduced immune capacity will be expressed as there would be no compensatory mechanism to counteract the mutation. This goes the same for any disadvantage brought on by mutations in the Y chromosome related to immune functions.

In contrast, females have a buffering mechanism to control for deleterious mutations by way of a phenomenon called X-inactivation. Because females are homologous for the X chromosome, expression of both of these chromosomes may induce a doubling-up effect, and so an evolutionary process was developed to attenuate this excessive “X dosing” by way of shutting off one of the X chromosomes so that the other one will be the one that gets expressed.

A clear example of X-inactivation are calico cats which are nearly always female. Their color pattern is due to X-inactivation which leads to cells in certain regions expression one color relative to other regions.

This creates a mosaic effect in females, in which some somatic cells may express one copy of the X chromosome while other cells may express the other. This allows for a built-in compensatory mechanism, as cells that express X-related deleterious genes will be compensated by those that don’t. Also, diversity in genes across the two X chromosomes may also infer greater immune diversity in females, and may be associated with the better outcomes seen in females for certain diseases.

Unfortunately, X-inactivation isn’t a perfect good, as evidence suggests that women are more likely to experience autoimmune diseases relative to men, and may be a consequence of a more robust immune response or x-inactivation biases that may increase expression of deleterious genes.

All this to say that immune function is inherent in one’s chromosomes, and the sex differences seen in vaccine adverse reactions cannot be separated from sex differences in immune responses.

When science articles begin to use such language as “sex at birth”, they completely gloss over the fact that sex is a crucial variable in outcomes from clinical trials and cannot be downplayed. If we are to figure out why young males are more at risk of post-vaccine carditis, we have to take into account sex as a variable. Using the phrase “sex assigned at birth” doesn’t do much from a molecular/genetic perspective, and only examines things from a clinical/social one.

Thus, it’s apparent that this change in language is not being dictated by scientists (at least I would hope not), but more so by ideologically-driven gender scholars and medical professionals who seem to distance themselves from actual scientific principles..

Consider Prasad’s argument about changing the structures of medical school that I examined previously.

Dr. Prasad reveals his "rethinking medical education" post was written by ChatGPT

Modern Discontent is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Shockingly (or maybe not so shockingly) Dr. Prasad just reve…

I won’t argue that Prasad in particular is trying to change the language used in medicine, but I also can’t deny that his top/down approach to medicine would lead to practicing physicians trying to dictate language changes that incorrectly misrepresent facts rooted in empirical, scientific evidence.

Put another way, those who argue against a scientific understanding of medicine, and really the world, are the ones attempting to dictate how science should be disseminated and taught.

In looking a bit deeper into the inclusion of “assigned at birth” as a phrase, it strangely seems that this correction may be due to self-reports in which an individual may provide their “gender” as a conflation of their sex, rather than sex as an innate biological characterization.

A 2016 opinion piece from JAMA3 makes the following remark suggesting why this language was included in studies:

NIH policies to enhance reproducibility through rigor and transparency require that researchers address and report relevant biological variables, such as sex, in human and vertebrate animal studies.2 The Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines reinforce that authors should provide an explanation in the methods section whether the sex of human research participants was defined based on self-report or was assigned following external or internal examination of body characteristics or through genetic testing or other means.4 When sex is based on self-report, it will be incorrect in a very small percentage of individuals because some individuals will not be 46XX or 46XY. However, in most research studies, it is not possible to conduct detailed genetic evaluation to determine the genetic make-up of all participants.

Authors reporting the results of clinical trials should analyze and report data separately for male and female study participants.3,4 Three compelling reasons drive the recommendation to stratify and report outcome data by sex, gender, or both. One reason is to avoid drawing incorrect conclusions. When results for male and female participants are combined, the average of aggregated male and female participants’ results may mask differences between them. The effects of an intervention in one sex might be greater than in the other; toxicity might differ; symptom profiles might differ; or one sex might experience more adverse effects.1 Failing to account for gender can also lead to spurious results. For example, gender, independent of sex, predicts poor outcomes after acute coronary syndrome.7

So this, again, seems to suggest that language used in science is being driven by colloquial, laymen misuse of these terms. Put another way, it seems like a correction that would otherwise not be needed if people understood what sex actually refers to. It’s apparent that such changes are due to the fact that people don’t seem to understand that gender and sex are distinct albeit with heavy correlations, in much the same ways that the word “hypothesis” cannot be conflated with the word “theory”, even though they are both used interchangeably.

The clarification provided between the use of sex or gender in clinical practice seems to fall along distinct lines (emphasis mine):

Sex is recognized implicitly as an important factor in clinical research. More work is needed to standardize the way sex and gender are reported and elucidate the way these characteristics function independently and together to influence health and health care. The following recommendations for reporting in research articles may improve understanding and comparability across studies, and help deliver truly personalized medicine: (1) use the terms sex when reporting biological factors and gender when reporting gender identity or psychosocial or cultural factors; (2) disaggregate demographic and all outcome data by sex, gender, or both; (3) report the methods used to obtain information on sex, gender, or both; and (4) note all limitations of these methods.

However, this again doesn’t do much to help deal with the issues in conflation and misinterpretation of science, especially by those who purport to argue under the guise of science without even engaging in science.

Maybe I’m being a bit persnickety here, but the fact that these changes in research are appearing with even more frequency raises real concerns about how the public comes to understand science.

Those who do not engage with science cannot dictate how science operates, and this doesn’t appear to be the case with the encroachment of ideology into the field.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA. Published online May 25, 2023. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.8823

Klein, S., Flanagan, K. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 626–638 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.90

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting Sex, Gender, or Both in Clinical Research? JAMA. 2016;316(18):1863–1864. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16405

Interesting concept, "trans ideology". This is partly the fault of the trans community for defining "trans" so broadly in the first place. This was intentional, in part just to get away from "transgender", which from the time it was coined was extremely broad in scope, but included a large subculture for which the word "transgender" meant "not transsexual".

What we have now is something else, and I don't even want to try to deal with it here. What does concern me is "assigned sex". Yes, this is a real thing for some people, especially in a world flooded with endocrine disruptors and other stuff that makes sexual development go wrong. Sexual development is certainly not a matter simply of XX vs. XY, and wouldn't be even if those were the only two possible configurations. Enzymes and hormones are part of the "other stuff". For a Y chromosome to do its job properly, these other things have to be intact. For a sampling of what can go wrong, see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8720965/

There are some interesting observations in this publication. See, for example, "2.2.2 17α-Hydroxylase, 17,20-Lyase Deficiency (P450c17D)". In one case we have "steroidogenesis in adrenals and gonads is severely impaired, causing deficiency of cortisol and sex steroids, with mineralocorticoid excess. Consequently, 46,XY fetuses are severely undervirilized while 46,XX sexual development is unaffected at birth (33). The typical presentation of this form of CAH is a phenotypic girl or adolescent with pubertal failure, including lack of breast development and primary amenorrhea, hypertension and hypokalemia (45)."

XY sex chromosomes, but typical presentation as "a phenotypic girl or adolescent with pubertal failure". Male genotype, female phenotype. Hmmm. Admittedly this is rare, as are other similar conditions. I came across this information 19 years ago when I was researching my own endocrine issues revolving around pregnenolone insufficiency and partial pubertal failure. CAH did not fit, in any known variant, but it came closer than anything else I was able to locate back then. I still look for new research from time to time, when I have spare time, which is never.

Also, there is this: https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2002/10000/Gender_verification_of_female_Olympic_athletes.1.aspx

A transwoman that transitioned surgically is usually at minimal risk for prostate cancer. The prostate shrinks away to almost nothing. Don't ask me how I know. An undersized pituitary can be quite a problem, or not. How would one know if it is? Empty sella syndrome diagnosis. How is it diagnosed? It can't be, as far as I know. (Empty/partially empty sella alone is diagnosed through MRI, been there, done that, but finding it doesn't tell you if it is a problem. Syndrome = yes, a problem, but no way to tell if that's what's causing the problem.)

Inquiring about it at least made for an interesting phone conversation with a UCSF endocrinologist.

I'm a copy editor. One of my former bosses once said that conservatives were responsible for this whole "gender" problem because they were too squeamish to use the word "sex" referring to male/female. I tend to agree.

Also, my OB told me my son was a boy at 12 weeks gestation. I said, "Are you sure?" He said, "Well, I sure hope so, because that's a penis." To me, that's why this whole "assigned at birth" is so ridiculous. What are those dumb "gender (should be sex, right?) reveal" parties for, if people are supposed to wait for the doctor to assign it at birth?