What exactly is "clinically meaningful" when it comes to Leqembi?

Part II: Where researchers, clinicians, and testimonials can't provide a clear explanation for what this expensive immunotherapy with serious side effects should do.

In the prior post I provided a bit of an overview to Study 301, which is a Phase III clinical trial for Leqembi. The results of this trial were the focal point for last Friday’s FDA advisory meeting, and were what was under scrutiny in order to determine if Leqembi should seek full, traditional FDA approval.

As noted, the main point of contention here lies with the argument over safety and efficacy of these immunotherapies, where safety concerns over brain swelling and bleeding, including possible deaths are under scrutiny, as well as what the actual efficacy of this drug is.

It has been argued, and voted unanimously by the committee, that a CDR-SB difference of 0.451 between the Leqembi group and the placebo group is “clinically meaningful”, and yet what does that exactly mean?

Can one accurately provide any description for how to translate a CDR-SB difference of 0.451?

As we’ll see, not many people can accurately detail what this exactly means, and instead will obfuscate this fact.

Note: When referring to speakers from the Open Public Hearing portion of the meeting, a link to that specific speaker will be provided under their speaker number, aside from Dr. Chandrin which I embedded directly in the article below.

Is a CDR-SB difference of 0.451 “clinically meaningful?”

Remember that the primary endpoint for Leqembi’s Study 301 trial, and really any immunotherapy trial for Alzheimer’s, is a statistically significant difference in CDR-SB score between treatment group and placebo group.

Here, Eisai and the FDA are arguing that the CDR-SB difference of 0.451 seen between the groups is both statistically meaningful, as well as clinically meaningful.

But as well-emphasized before, how does one interpret these findings to be clinically meaningful1?

As an example of the confusion over what Leqembi’s primary endpoints suggest, one speaker, Dr. Rishmarama Chandrin (Speaker #132), a practicing physician and assistant professor at Yale’s School of Medicine, provides an account of patients asking her about Leqembi since its accelerated approval in January. Dr. Chandrin was hoping that the meeting would provide clearer explanations of the drug’s safety and efficacy.

Suffice it to say, Dr. Chandrin was left wanting, as she raised rightful concerns over serious adverse events and how to even interpret the CDR-SB difference (timestamped below):

As shown above, neither Dr. Chandrin nor her coworkers can discern what these results are supposed to translate into in the real world.

But this was also the case when initial results of the Phase III clinical trial came out. For instance, an editorial in The Lancet3 published in December 2022 even remarked that the clinically meaningful use of Leqembi is unknown (emphasis mine):

After such a long and fruitless wait for a successful therapy for Alzheimer's disease, a phase 3 trial showing efficacy on clinical outcomes is welcome news. However, a 0·45-point difference on the CDR-SB, an 18-point scale, might not be clinically meaningful. A 2019 study suggested that the minimal clinically important difference for the CDR-SB was 0·98 for people with mild cognitive impairment and presumed Alzheimer's aetiology, and 1·63 for those with mild Alzheimer's disease. Furthermore, development of ARIA—seen in one in five patients taking lecanemab—could potentially lead to unmasking, introducing bias.

The 2019 article in question appears to be a study from Andrews, et al.4, in which researchers wanted to determine what degree of cognitive decline may be considered clinically meaningful.

That is, at what degree of decline will the decline be noticeable by clinicians and warrant further interventions?

The term used by Andrew, et al. is called the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), as defined below (emphasis mine):

A key challenge in clinical trials to evaluate the effects of interventions related to Alzheimer's disease (AD) and dementia is to assess the clinical—rather than statistical—significance of differences in outcomes across trial cohorts. [1] The concept of a minimal clinically important difference (MCID)—also known as minimal important difference, minimal clinically relevant change, or minimum detectable change [2]—can be valuable in this context. MCID is “the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and cost, a change in patient's management.” [3]

In assessing MCID for Alzheimer’s Andrew, et al. looked at the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set, which collected data on patients with different degrees of cognitive decline between the years of September 2006 and September 2015.

Data collected included patient demographics, as well as indications by clinicals as to whether a patient appeared to show noticeable cognitive decline (emphasis mine):

Data for the UDS are collected and recorded directly by trained clinicians and contain, among other measures, information on (1) patient demographics, medical history (including medication use), and family history; (2) cognitive and functional status, measured using validated instruments such as the MMSE, CDR, and the FAQ; and (3) behavioral symptoms, evaluated using the NPI-Questionnaire. Importantly, at each visit the NACC data include a derived indicator of whether a clinician has observed meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes relative to previously attained abilities.

Data collected were based on annual visits, with patients who showed two consecutive visits within the ADC timeframe having their information included.

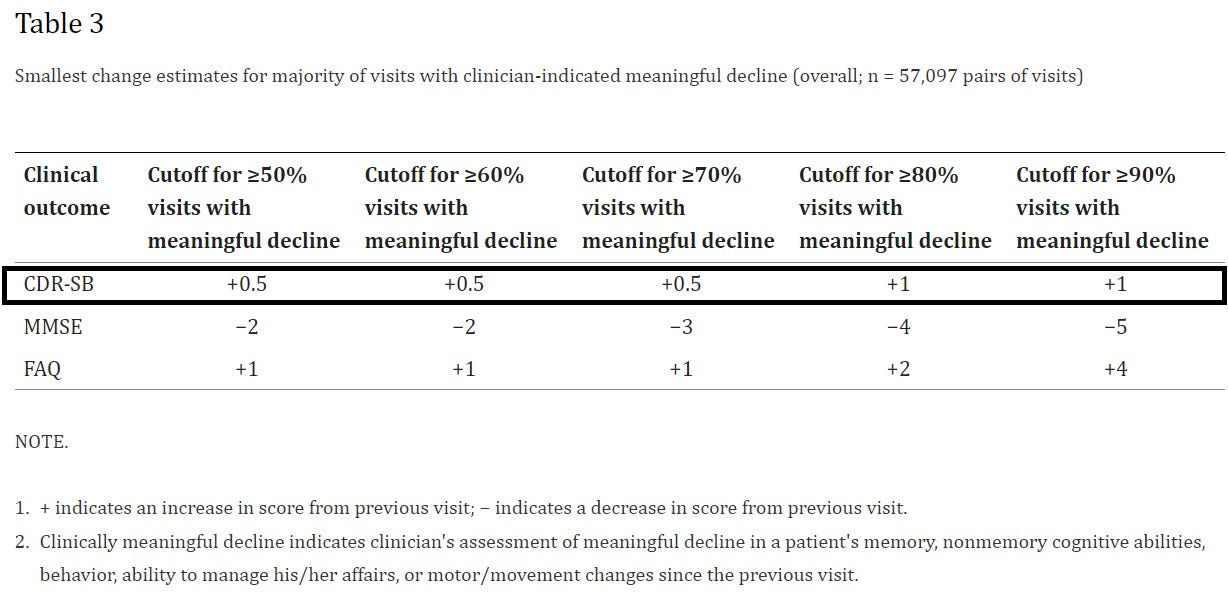

When comparing clinician remarks to CDR-SB scores, researchers noted that a CDR-SB score increase of around 0.5 was needed for at least 50% of clinicians to note meaningful cognitive decline in their patients.

However, this threshold was also dependent upon the degree of cognitive decline in the patient upon first visit, such that the greater the disease severity the greater the MCID upon subsequent visits needed to be in order for clinicians to recognize meaningful decline (emphasis mine):

In addition, on average, the magnitude of changes in CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ associated with clinician assessment of meaningful decline increased with increase in disease severity (Fig. 1 and Table 2). For example, among those with a clinically meaningful decline, the mean change in CDR-SB scores was 0.54 for patients with normal cognition (ES: 0.29; SRM: 0.34), 0.98 among those with MCI-AD (ES: 0.44; SRM: 0.57), 1.63 for those with mild AD (ES: 0.54; SRM: 0.70), and 2.30 for the moderate-severe AD cohort (ES: 0.51; SRM: 0.81).

This appears to be where The Lancet got their numbers from. It’s interesting that the minimal change in CDR-SB scores increased with disease severity, although it’s likely due to the fact that early changes in cognition are far more noticeable. That is, a patient who shows early signs of forgetfulness may be more noticeable relative to prior months than a patient already in the throws of severe cognitive decline who is heavily dependent on others. Changes in the latter stages may be hard to discern if one is likely to show a good deal of debilitation.

So far, a lot of this may seem like unnecessary information, but remember that we are being told that Leqembi’s results are “clinically meaningful”, with some testimonies by clinicians providing Leqembi even arguing that they show clinically significant slowing of decline.

So how do we interpret Andrew, et al.’s findings within the context of Leqembi?

Consider a clinician who sees two patients within the early stages of cognitive decline. Both of the patients are similar across demographics, and they score with similar CDR-SB scores noting mild cognitive impairment (MCI). However, one patient goes on to receive Leqembi while the other one doesn’t. The clinician is unaware that one patient is taking Leqembi (likely not to be the case in a real-world setting, but let’s entertain this scenario).

When both patients return to see the clinician after 18 months, would the clinician, by way of assessing the patient and measuring CDR-SB scores, be able to determine which patient received Leqembi, and which one did not?

If Andrew, et al.’s findings are correct, the answer to this would likely be NO.

That is, the difference between the Leqembi patient and the placebo patient, with a CDR-SB difference of 0.451, may not be noticed by most clinicians as it does not meet the threshold of MCID. For instance, if more than half of the clinicians would require a score of at least 0.5 to recognize meaningful decline, odds are most clinicians may not be able to discern any difference unless otherwise told that the patient is on a treatment regimen and possibly conflating expectations with actual evidence.

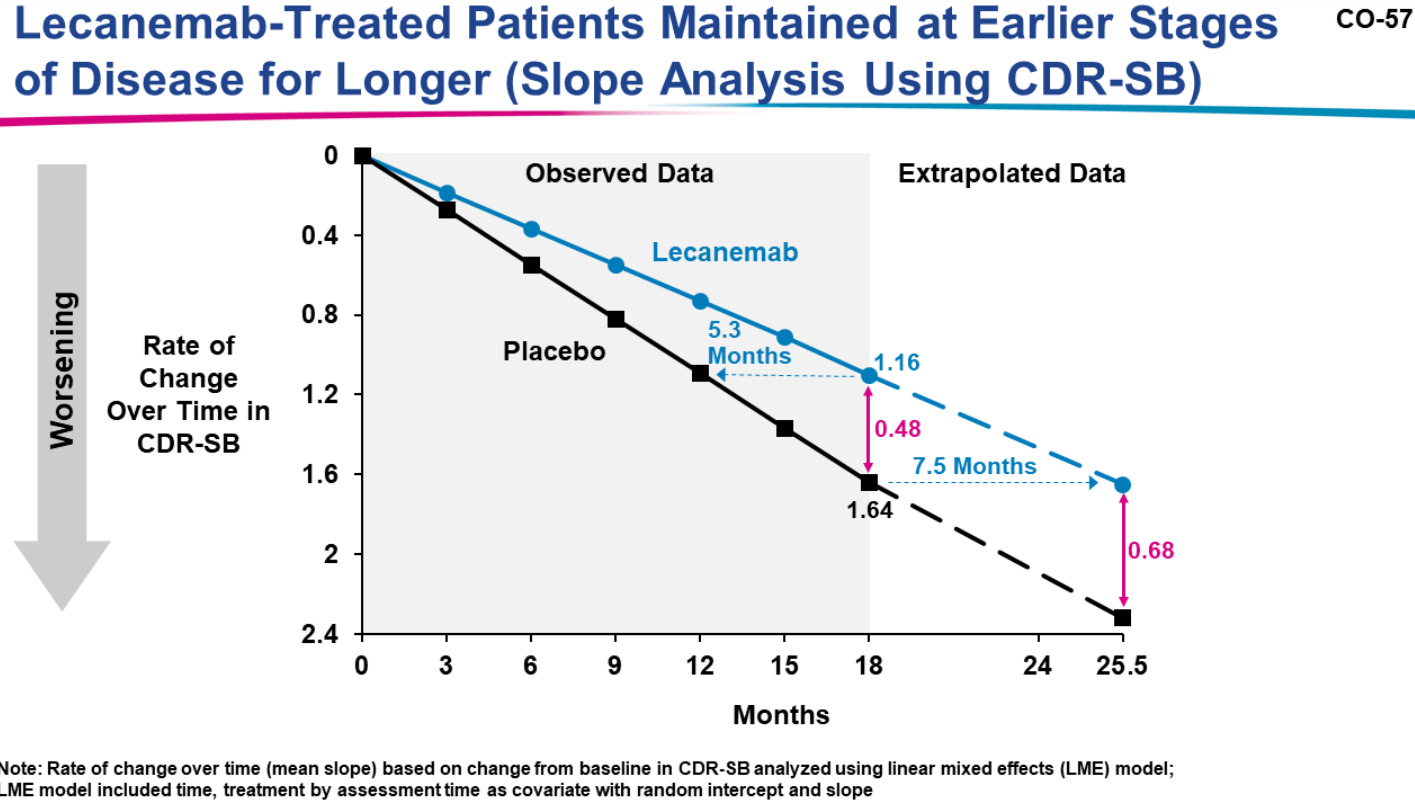

Note that when Eisai extended their results to an endpoint of 25.5 months the assumed difference in CDR-SB scores between the two groups was 0.68 (Slide 57 from Eisai’s presentation):

So even at this extended endpoint there was still be a question of whether a clinician would be able to discern whether a patient was on Leqembi or placebo through assessment since 24 months in would still not meet MCID between groups (note that Andrew, et al. is using a CDR-SB score of 1 to make this comment).

But while all of this is occurring note that cognitive decline is continuing in both groups. The immunotherapy, after all, is argued to slow cognitive decline, not stop or reverse it.

Note that in both groups a mean increase of a CDR-SB score greater than one was seen by the 18-month endpoint, as noted in the above slide which suggests a 1.16 increase in the Leqembi group vs a 1.64 increase in placebo.

So even as we argue over how to interpret this 0.451 value, it’s apparent that patients are showing clear cognitive decline regardless of treatment.

Remember that a move from a CDR-SB domain score of 0 → 0.5 is considered a move from unimpaired → impaired, while a move from 0.5 → 1 is considered a move from impaired to dependent.

In this case, one can clearly see that both groups would show either some degree of impairment or dependency, when this may not be noticeable between the two groups.

But what’s important to recognize is that while the difference between the two groups broadens over time, so too does the threshold of MCID needed for clinicians to recognize cognitive decline. In short, this likely would mean that a therapeutic that does not meet early MCID would likely never meet MCID. Even after years of use with Leqembi clinicians may not be able to recognize discernable differences between Leqembi users and placebo, as by that point patients may have moved onto more moderate/severe classifications of Alzheimer’s, which have a much greater MCID as remarked by Andrew, et al. in the prior excerpt.

In summary, there are two paradigms of efficacy that have to be considered:

Clinicians, unless otherwise told, may not be able to discern whether a patient is receiving Leqembi in the long-term or whether they are not seeking out treatment outside of standard of care.

Irrespective of treatment or placebo, patients across the board still show noticeable/recognizable cognitive impairment as their CDR-SB scores continue to increase over time.

Thus, a real-world placebo effect needs to be recognized, in that clinicians, as well as the patients who receive these treatments, spurred by hope and no other avenues for help, may bias themselves into believing that they are seeing some form of reduced cognitive decline when the real evidence is hard to determine.

This raises a clear question of how well these primary endpoints actually translate in the real world.

Should patients be seeing “improvement”?

Considering the heavy degree of bias that is likely being used to argue Leqembi’s clinical significance, what I found rather strange in some of the personal testimonials is that some of the remarks made seem to go entirely against what is expected of these therapeutics. That is, some of the remarks from those on Leqembi, as well as loved ones, seem to be more in-line with improvement, rather than slowing of cognitive decline.

For instance, Joanne Bridges (Speaker #11) speaks of her husband Jerome Bridges, who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s on October 28th, 2019. Jerome was considered an ideal candidate for Leqembi, and was enrolled in the AHEAD study.

She mentions that after taking Leqembi, “he became more talkative, smiled, was keen to help around the house, started reading again, and listening to his favorite jazz music.”

Jerome is currently taking weekly doses of Leqembi.

Ira (Speaker #21) speaks of his partner Mary who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in late 2018. Mary was enrolled in a clinical trial for Leqembi in 2019, although Ira and Mary were later alerted that Mary was in the placebo group. She was later enrolled in the treatment group in August 2021 during the open-label portion of the trial.

Ira makes the following remarks: “All I can tell you is this: not long, some weeks, maybe months after Mary started her Leqembi infusion, I noticed that her short-term memory abilities had improved some. She said she felt good. She was recalling recent events…”

Ira goes on to mention that Mary’s neurologist compared MRI scans from 2018 to 2022, and remarked about how slow Mary’s Alzheimer’s was progression.

The two instances above are not the only testimonials provided by those directly taking Leqembi or know of loved ones who were.

I also caution wading into this territory without appearing insensitive. It should be made clear that Alzheimer’s is a debilitating disease that no one should suffer through, and there’s a clear understanding for why people are seeking out possible treatments to this disease.

And yet, I can’t help but hear remarks such as the ones above, which appear to allude to improvements on Leqembi, without raising serious questions about whether this is actually occurring. Given that Leqembi is intended to slow the progression, is it feasible to argue that people should show signs of improvement?

The clinical trials clearly do not provide mention of improvement, just slowing. Remember that Adulhelm came under fire when Biogen/Eisai re-examined their clinical findings and argued that cognitive improvement was seen in a small cohort of patients, so shouldn’t these remarks over improvements also be met with a degree of skepticism as well?

I can’t blame patients for these remarks, but I think this points to an obvious issue in which patients are not provided accurate information in regards to what should be expected of this therapeutic, following along with the remarks made by Dr. Chandrin.

They are either provided a large sense of hope, or may not be able to understand the relevancy of CDR-SB values, with clinicians not being able to provide clear definitions themselves and relying on Eisai or the FDA to provide clear guidance on what is “meaningful”.

So should we really be seeing such remarks towards improvement for a drug that otherwise should not be showing improvement?

What does it mean to have “mild” Alzheimer’s?

If we look back at the criteria for mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzeimer’s note that the CDR-SB range of scores included under this category fall within the range of 0.5 to 6.

By all accounts, it’s not hard to look at this range and consider that many different degrees of disease severity would be included under the umbrella of “mild”.

If we use the criteria for impairment and dependency, this range would tell us that someone diagnosed with mild MCI or AD would at least show one form of impairment within one domain (CDR-SB score of 0.5), and at most show dependency across all 6 domains (score of 6).

Given that early treatment appears to be best with Leqembi, one can easily argue that someone who presents with far lower CDR-SB scores may respond far differently than someone who has a much larger score, and yet is still considered “mild”.

This raises some questions about who may actually benefit from these treatments. It may also raise the question of whether there may be far higher risk of ARIA in those who score higher on the CDR-SB score.

Essentially, were those who showed the greatest benefit with Leqembi those who already had very low CDR-SB score to begin with, and were those who showed higher scores more prone to ARIA and other serious adverse events?

When examining the testimonials provided, it’s hard to determine the degree of disease progression among these individuals aside from descriptions.

However, I found remarks by one person in particular, Donna Kim Murphy (Speaker #16), to be rather apt when considering how “mild” is being defined.

Dr. Murphy is a neurologist/neuroscientist with concerns over her grandmother, as well as herself as it relates to Alzheimer’s.

She remarks that her 95-year old grandmother is classified as having “mild” dementia based on clinical scales, and yet her grandmother suffers from delusions of persecution, which has exhausted her mother who serves as her primary caregiver and left her on edge and sick (to whom the her is referring to is a bit unclear, although I’m leaning towards Dr. Murphy referring to her mother).

It’s hard to consider such a position, and argue that a drug that barely shows any meaningful decline is worth considering within this context, which may just serve to prolong the suffering of both the patient and caregivers.

In the same ways that many diseases may manifest differently between individuals, it’s quite clear the same must be said as it relates to Alzheimer’s. Just because some people experience manageable memory loss does not mean all people who have mild dementia will only experience memory loss. The burden is likely not be even on caregivers and patients alike, so to categorize these individuals all under the umbrella of “mild” tells us nothing about disease progression, manifestation, and burden on loved ones.

In this case, not only is the endpoint difficult to interpret, but the inclusionary criteria and definition of “mild” is so broad that one has to consider an apples-to-oranges comparison even among those categorized within the same group.

Compared to what?

I’ll save remarks on conflicts of interest for the next post. What I find rather striking in the mainstream reports that I’ve seen is the lack of references to Biogen/Eisai’s first attempt at approval with Adulhelm. It’s almost as if all of the remarks on Leqembi are done within a vacuum sans any comparison to Adulhelm.

I actually find this comparison to be completely necessary within this context, given the fact that Adulhelm was met with such criticism while Leqembi is being met with such appraisal.

Because if we compare the endpoints for these two therapeutics we’ll find that there’s not much difference between the two.

Remember that Adulhelm reached a CDR-SB difference of 0.39 among the highest dose, non-carriers within their EMERGE clinical trial (APoE4 carriers were provided a lower dose of 6mg/kg biweekly Adulhelm in contrast to the 10 mg/kg biweekly in non-carriers).

Tampi, et al.5 provides several accounts of people who have questioned the results from both the ENGAGE trial as well as the EMERGE trial (the former not being the primary endpoint; the latter raising question of actual significance for these results).

I won’t rehash them here and refer readers to the category Reviews of evidence by independent researchers.

What’s important to remark is the undeniable fact that a score of 0.39 and a score of 0.45 are extremely close. Thus, if Adulhelm has received widespread criticism, why hasn’t Leqembi for having results similar to that of Adulhelm? And more importantly, why is it as if Leqembi is Eisai’s first attempt at getting approval, as if precedent hasn’t already been set in regards to question the accelerated approval by which all of these drugs are receiving?

I’ll save a bit of this discussion for the next post, but consider the remarks made by Joanne Pike (Speaker #5), CEO and president of the Alzheimer’s Association, where she mentions that many of the scientists/clinicians who signed the letter addressed to the advisory committee were skeptical/critical of Adulhelm, and yet within that same breath remarks that there’s no doubt Leqembi clears the bar set by the FDA.

I have a lot to say about Pike’s remarks, and it points more to a bullying tactic seen by advocates to dismiss those who raise serious criticisms or concerns related to the safety and efficacy of these drugs- sounds a bit familiar to other things that received accelerated approval.

But in this I find it contradictory to make such remarks, as the ones I summarized above, as if to say that a difference of 0.06 itself clear the hurdle from controversy/lack of efficacy to clear, irrefutable evidence of efficacy when in reality I would argue that these comparable results show anything but.

Across the board it appears as if no clear indication of efficacy is actually provided, and yet this costly drug with serious side effects appears to be receiving full approval.

If neither clinicians, advisers, regulators, nor even patients can describe what Leqembi’s effectiveness entails, then how are we as the public to view these treatments with anything but skepticism.

I will say, however, that in looking at some of the remarks, including those within the Open Public Hearing, I was rather surprised to the degree in which people not only defended Leqembi (which is their perspective), but the degree in which many speakers attempted to downplay concerns over safety and efficacy as nothing more than sowing seeds of doubt, or coming from people who are misinterpreting the data, or providing misinformation.

It’s a strange thing to see that the same tactics used by COVID vaccine zealot are appearing within this same meeting over Leqembi. I think this speaks more of the current paradigm that I have mentioned before, in which both pharmaceutical manufacturers as well as regulatory agencies such as the FDA will leverage the hope and want of a drug against any dissenting voices.

Those who question the safety and efficacy of any accelerated drug, especially those in which the public is yearning for help via treatment for, are doing a disservice and not caring enough for those who are suffering from the disease in question.

More on that in the next post, which hopefully will be a summary of all things discussed.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

In contrast to statistical significance, a clinically significant treatment is one which is argued to see a real-world, noticeable effect on the patient being prescribed the treatment, and so the remarks over clinical significance requires one be able to determine whether the patient being prescribed Leqembi actually appears to show a slowing of decline.

As is the norm for these meetings, near the end the meeting becomes open to several people who are invited to speak on the drug/therapy under review, with this portion labeled as Open Public Hearing. People chosen are usually advocacy groups, people who have used the treatment, or clinicians/scientists who weigh in and provide anecdotes or perspectives on whether the drug in question should be approved.

The Lancet (2022). Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease: tempering hype and hope. Lancet (London, England), 400(10367), 1899. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02480-1

Andrews, J. S., Desai, U., Kirson, N. Y., Zichlin, M. L., Ball, D. E., & Matthews, B. R. (2019). Disease severity and minimal clinically important differences in clinical outcome assessments for Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimer's & dementia (New York, N. Y.), 5, 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2019.06.005

Tampi, R. R., Forester, B. P., & Agronin, M. (2021). Aducanumab: evidence from clinical trial data and controversies. Drugs in context, 10, 2021-7-3. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2021-7-3