The NSAID/COVID Paradox

And how early consternations affected over-the-counter COVID treatment options.

The early months of the pandemic were rife with all sorts of confusing and conflicting information. Many of this conflicting information somehow made it into the world of at home treatment through over the counter remedies.

You may have heard an early warning1 that people should avoid taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if they contracted COVID, and instead they should take Acetaminophen (Tylenol) instead. It’s a rather strange warning to make, but with the level of uncertainty that came with the pandemic many people may have heeded whatever advice was available, especially from higher up institutions.

But as the pandemic progressed even more conflicting information came out about NSAID use and COVID, and now there is not much warning against the use of NSAID’s as of this day.

So what happened to change this dire warning? Was it a warranted hesitation in over-the-counter (OTC) use for an uncertain pandemic? Or was this an unfounded concern that may have limited the ability and resources for early COVID treatment?

NSAIDs Brief Introduction

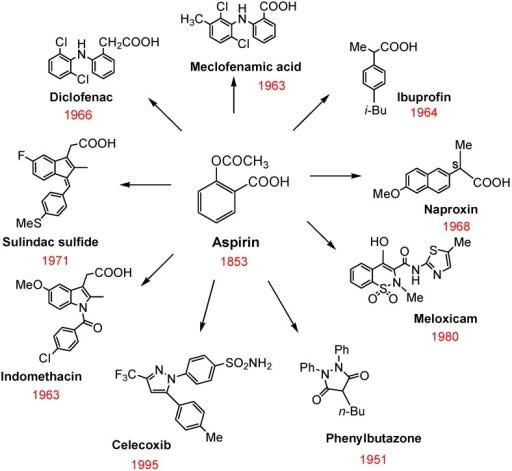

NSAIDs are a class of drugs widely available OTC and include several different drugs such as Naproxen, Aspirin, and Ibuprofen. A few NSAIDs and their structures are shown below.

Some of the therapeutic effects of NSAIDs include antipyretic (fever reducer), anti-inflammatory, and analgesic (pain reliever) effects.

These therapeutic effects mainly come from the targeting of the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway. The COX pathway is responsible for converting the molecule arachidonic acid into other structures such as thromboxanes, prostaglandins, and prostacyclins, which are responsible for activating various platelet, vasodilate, and inflammatory pathways2. By inhibiting the production of these other compounds you can prevent the unwanted symptoms such as fevers and muscle aches.

Note that Acetaminophen does not target the COX pathway and therefore it is usually not considered an NSAID, although it’s inclusion as an NSAID may happen.

The French Fallacy

Although NSAIDs have been widely available and widely used for many years, questions have been raised in regards to their actual benefits when used to treat fevers during an infection. Emerging evidence suggested a possible correlation between NSAID use and reduced bacterial clearance in recent years, raising concerns as to the appropriate use of these drugs when ill.

Most of this work was carried out by French pharmacovigilant networks which analyzed various studies where NSAIDs were used for fevers in association to bacterial infections (Micallef, et. al. June 2020):

In 2015, the French Regional Pharmacovigilance Centers (CRPVs) collected and assessed several clinical observations of a severe, sometimes fatal, bacterial infection in patients, who took an NSAID for a fever or a pain associated with a bacterial infection. These cases led the National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM) to request a new expert report to the CRPVs, following the previous report in 2002. This new report (presented in 2016) has resulted in the emergence of a signal for severe pulmonary infections, as well as proposals of information and action [7], [8]. In 2018, new observations of serious adverse effects led to a third pharmacovigilance report that focused on severe bacterial complications with ibuprofen and ketoprofen, used for fever or non-rheumatic pain. This last report (presented in 2019) enabled to consolidate the signal, on the basis of the analysis of pharmacovilance cases, and recent pharmacoepidemiological and experimental studies [9], [10], [11].

Further questions continued to be raised as to whether lung infections would be affected by the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities of NSAIDs. Prior animal studies also indicated that NSAID use may increase ACE-II expression- something that would likely be detrimental if true. Overall, the accumulating evidence raised questions as to whether widespread use of NSAIDs in the wake of COVID would either be detrimental or beneficial.

Many of these arguments were summarized in a report by Micallef, et. al. 3 (excerpt above) released in March 2020, and its warnings led the medical community to scramble to assess whether NSAID use should be discouraged.

Further commentary was provided by Cure, et. al.4:

NSAIDs in COVID-19 can cause some other complications. PGE2 blocks the release of leukotriene through its receptors in mast cells. Inhibition of the COX-1 with non-selective NSAIDs activates the formation of the leukotrienes from arachidonic acid. Increased leukotriene release may trigger bronchoconstriction and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [10]. COVID-19 infection often causes ARDS. Using NSAIDs can cause serious side effects, especially in patients infected with severe COVID-19.

With additional remarks made in a response by Micallef, et. al, August 2020.5:

As consequence, a cautious approach should be followed with the initiation of NSAIDs for fever or cough related to COVID-19 due to the increased risk of the well-known adverse effects of NSAIDs in the specific setting of COVID-19 in addition to the possible risk of worsening the disease. The existence of a safer alternative (i.e., paracetamol at the recommended dose) makes this recommendation of common sense even more legitimate.

And so the precedent was set, without any concrete evidence, that NSAIDs should be dissuaded from use against COVID.

Many institutions took it upon themselves to instead offer Acetaminophen as the drug of choice, and it explains why many people were told to take Tylenol when they went to receive a COVID test- I remember I did when I went for a COVID test, and I’m sure many others did as well.

But this also created a large rift within the medical community. For those who depend on NSAIDs are they more at risk of developing more severe COVID? Should people stop NSAID use in general, even for instances where they may not have COVID?

As we’ll come to see, these quick assumptions and hasty medical decisions may not have been rooted in evidence.

Where’s the evidence?

Since these early warnings research has begun to come out with respect to NSAID use against COVID, and whether COVID truly may be worsened by use of NSAIDs.

In one study from The Lancet6 patient data from over 72,000 patients was collected across the UK and matched based on whether patients took NSAIDs before admission to a hospital due to a COVID infection. Aspirin was excluded as a possible NSAID since it is used to treat many other diseases. After various sensitivity analyses the researchers concluded that there was not a statistically higher rate of death and illness severity between those who took NSAIDs prior to admittance and those who didn’t.

The authors indicated in their discussion (emphasis mine):

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, questions were raised concerning the safety of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19, with suggestions that these drugs were leading to more severe disease in a some patients.2, 30, 31 Our data show that patients taking NSAIDs did not have more severe symptoms or poorer outcomes than those not taking NSAIDs. These data support community studies showing that NSAID users did not have higher rates of hospitalisation with COVID-19 and smaller studies of in-hospital outcomes, which found NSAID use was not associated with poorer outcomes. A propensity matched data linkage study of patients with osteoarthritis taking NSAIDs in the community setting found no difference in the risk of developing COVID-19 or dying from the disease.13 Compared with our data and previous studies our consortium has published, this data linkage study13 did not find any differences in risk factors for mortality after COVID-19, which is probably due to the very small numbers of patients with COVID-19 in the study. To our knowledge, our study is the largest study of in-hospital outcomes of patients with COVID-19 to date. Considering all the evidence, if there was an extreme effect of NSAIDs on COVID-19 outcomes or severity, this would have been observed in one or more of the studies that have been done, including the present study.

This was one of the first large studies to suggest that NSAIDs may not be more harmful than beneficial. Unfortunately, this study did not indicate that NSAIDs may be beneficial when used to treat COVID, and the inclusion/exclusion of various NSAIDs7 from the study should take into account the limitations of the study. However, if the concern lies specifically on the detrimental effects of NSAIDs, this study should at least provide some evidence countering the initial NSAID concerns.

A more recent study by Reese, et. al.8 looked at patient outcome across 38 centers and over 840,000 patients (only up to 19,000 were included in the NSAID/non-NSAID group). Patients were included if they were admitted to a hospital and took an NSAID9 before or on the day of admittance, and up to a day after hospital admittance.

When propensity matching was conducted, the researchers noted a higher rate of moderate COVID infection in patients previously taking NSAIDs. Interestingly, the researchers noted that other measured outcomes were lower in those who took NSAIDs over the control group.

The researchers note this contrast in their discussion (emphasis mine):

Our findings did not show an association in hospitalized COVID-19 patients between NSAID use and increased COVID-19 severity, or increased risk of invasive ventilation, AKI, ECMO, and all-cause mortality. In contrast, we identified a significant association between NSAID use and decreased risk of these outcomes. These results are in accordance with those of some previous studies: NSAID use was reported less frequently among hospitalized patients than non-hospitalized patients [16]; a study on 1305 hospitalized COVID-19 patients showed that use of NSAIDs prior to hospitalization was associated with lower odds of mortality as assessed by multivariate regression analysis [25]; finally, the OpenSAFELY study demonstrated a lower risk of COVID-19-related death was associated with current use of NSAIDs in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis [28].

Further evidence of this possible beneficial effect of NSAID use came from a widely circulated Israeli10 preprint in which those who routinely took Aspirin for cardiovascular disease had lower incidences of COVID hospitalization, reduced hospital stay, and lower rates of death.

There are a few caveats to these studies. No consistent NSAID was examined in these studies, and the exclusion/inclusion criteria for Aspirin and Acetaminophen across various studies may also affect the results and outcomes. Patients may also unknowingly have taken NSAIDs or a product containing an NSAID prior to hospital admission or entry into a study, which would improperly place them into the control group.

Even with these caveats the evidence continues to mount that there are no verifiable evidence of worse outcomes in those who take NSAIDs to treat COVID, and some studies reflect a possible therapeutic, beneficial effect instead- all of which counter the initial hesitations put forth during the uncertain times of COVID.

And so one has to wonder for what reason such little anecdotal evidence was heeded with such heavy veracity, and why so many were quick to make such assertions against NSAID use without any verifiable evidence- we are in the era of invoking RCT, double-blind studies after all.

Fear over practice

The beginning of the pandemic was a time of great confusion and fear. No one knew how dangerous COVID would be, or that it would become the global pandemic that it now is.

Within those uncertain times were large controversies over which medications may actually be beneficial against COVID, including Hydroxychloroquine and later Ivermectin- drugs many reading this are likely to be aware of by now.

And even with those drugs we saw a strong divide within the medical community, so in some sense the hesitations against NSAID use may be somewhat warranted.

However, the widespread availability and use as a first line of aid raises many doubts as to why such a cheap and widely available drug would be dissuaded to such an extent, especially as there appears to be no conclusive evidence to support such actions.

Instead, it seems even more apparent that the evidence doesn’t fit the original warnings.

This type of approach has become all too commonplace during the COVID era. As it relates to lockdowns and masking there really was no clear evidence to support such policies, and yet it was demanded that the public adopt these behaviors over fears- better safe than sorry. But as we can see these measures not only proved to be ineffective, but they may have actually been detrimental to one’s health and liberties.

Indeed, many doctors warned about implementing these new, unfounded NSAID policies. Take these concerns from a group of doctors in Milan11 who were thrown into the middle of the COVID outbreak:

The effects of this warning has been very deleterious on our patients, especially on those who need to use these drugs for long periods for their medical conditions: NSAIDs allow these patients to lead a good quality of life, although we acknowledge that the prolonged use of these drugs may cause side effects, including kidney failure, liver failure, gastric ulcers, asthma attacks, heart and circulatory problems, and a partial immune depression [4].

Being based in Milan, we, more than others, are directly experiencing the devastating effects of this pandemic. We have been ready, and we still are now, to take any useful measures to reduce its impact on our population, without underestimating any possible new scientific information. Nevertheless, albeit in the midst of a general intellectual and emotional confusion, we try to maintain our scientific judgment, and would like to underline the danger of unproven and unfounded information, especially when spread out through mass and social media, which directly reach the general population without any filter. […]

Despite the common global interest in preventing our patients from suffering the most serious consequences of this new infection, it would be dangerous to stop some of these drugs based on not confirmed data. The effects of such suspension could certainly worsen the conditions of some patients, adding a supplementary burden on our health providers who are already overwhelmed by this enormous number of serious Covid-19 cases.

So it is not through fear that medicine is practiced, but through the ability to remain steadfast and hold independent ideas in the face of uncertainty. Irrespective of whether the evidence is there, doctors and the public should have the ability to apply their own risk assessment, analyze the information for themselves, and draw their own conclusions as to how they deal with adversity.

The concerns over NSAID use in COVID was unsubstantiated, and further evidence has rebuked these unfounded, circumstantial anecdotes that may have detrimentally altered the way many COVID infections were dealt with.

As of now, there is not much talk about NSAID use. Whether the public’s fear of the matter died down naturally, several websites, including the FDA’s own website, continue to suggest Acetaminophen (Tylenol) over NSAIDs when there continues to be no evidence supporting this decision. There’s even a large likelihood that these warnings played no real role in the minds of the public.

There’s no real way to measure the possible damages from such erroneous decisions, but this is nothing more than a clear indication as how the words of institutional figures can sway the attitudes and behaviors of those in the medical profession, regardless of whether that is rooted in scientific principles.

Another article can be found on webmd.com

https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20200318/coronavirus-nsaids-experts

van der Heide, Huub & Koorevaar, Rinco & Lemmens, J & Kampen, Albert & Schreurs, Berend. (2007). Rofecoxib inhibits heterotopic ossification after total hip arthroplasty. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 127. 557-61. 10.1007/s00402-006-0243-1.

Micallef, J., Soeiro, T., Jonville-Béra, A. P., & French Society of Pharmacology, Therapeutics (SFPT) (2020). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapie, 75(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.003

Cumhur Cure, M., Kucuk, A., & Cure, E. (2020). NSAIDs may increase the risk of thrombosis and acute renal failure in patients with COVID-19 infection. Therapie, 75(4), 387–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2020.06.012

Micallef, J., Soeiro, T., & Jonville-Béra, A. P. (2020). COVID-19 and NSAIDs: Primum non nocere. Therapie, 75(5), 514–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2020.07.008

Drake, T. M., Fairfield, C. J., Pius, R., Knight, S. R., Norman, L., Girvan, M., Hardwick, H. E., Docherty, A. B., Thwaites, R. S., Openshaw, P., Baillie, J. K., Harrison, E. M., Semple, M. G., & ISARIC4C Investigators (2021). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and outcomes of COVID-19 in the ISARIC Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK cohort: a matched, prospective cohort study. The Lancet. Rheumatology, 3(7), e498–e506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00104-1

The study excluded Aspirin, and it also limited measures of Ibuprofen since Ibuprofen is available through prescription only in the UK.

Reese, J. T., Coleman, B., Chan, L., Blau, H., Callahan, T. J., Cappelletti, L., Fontana, T., Bradwell, K. R., Harris, N. L., Casiraghi, E., Valentini, G., Karlebach, G., Deer, R., McMurry, J. A., Haendel, M. A., Chute, C. G., Pfaff, E., Moffitt, R., Spratt, H., Singh, J. A., … Robinson, P. N. (2022). NSAID use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a 38-center retrospective cohort study. Virology journal, 19(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01813-2

Acetaminophen and Aspirin where exclusionary factors for the same reason as The Lancet article. This is an instance where Acetaminophen was considered an NSAID.

Merzon, E., Green, I., Vinker, S., Golan-Cohen, A., Gorohovski, A., Avramovich, E., Frenkel-Morgenstern, M., & Magen, E. (2021). The use of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease is associated with a lower likelihood of COVID-19 infection. The FEBS journal, 288(17), 5179–5189. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15784

de Girolamo, L., Peretti, G. M., Maffulli, N., & Brini, A. T. (2020). Covid-19-The real role of NSAIDs in Italy. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research, 15(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01682-x

From the start of the Wuhan outbreak there has been a tendency among medical experts and researchers to seize on a particular data point and then not update their understanding with fresh data.

Another example of this was the early estimate that 20% of COVID cases would fall into a severe or critical classification. Even in China and particularly internationally, the publicly available data never really supported that percentage.

Closer inspection of the "official" estimate put out by the WHO among other sources indicated it came from a single study of Wuhan cases, which then became embedded in the prevailing narrative.

https://allfactsmatter.substack.com/p/narrative-fail-were-missing-some?s=w

Having dealt with catastrophic technology infrastructure failures during my career as a Voice and Data Engineer, I am very sympathetic to the position doctors are in at the outset of a major disease outbreak: information is sparse, data is constantly coming in largely unstructured, and what makes sense today can make no sense tomorrow.

However, the object lesson should always be a modicum of humility: recognize that the data is in a state of flux, recognize that the best available understandings not only are subject to change, but are likely to change, and retain the intellectual flexibility to adapt one's thinking to new data as it becomes available.

Reading this discussion about NSAIDS, it strikes me as yet another example of how the medical community failed to hew to that standard regarding COVID.

If California style misinformation laws become the norm (Sb2098), the problems you listed will go away. The law prohibits doctors from speaking up or disagreeing with Dr. Gavin Newsom.