The Importance of Sleep

Why we should be sleeping more now than we have before.

With renewed fear and anxiety brewing up with the onset of Ba.4/Ba.5, people are looking for ways to prevent getting sick or alleviating their illnesses. This includes masking and more vaccinations, or therapeutic compounds such as PAXLOVID, Molnupiravir, or even alternative options such as Hydroxychloroquine or Ivermectin.

However, as people scramble to find something to take, there continues to be a lack of messaging surrounding other options. At the same time people continue to operate under the pro-vax/anti-vax paradigm, how many people have lost weight, gotten more sleep, or have gone outside on a regular basis? It’s not the drugs or vaccines that we take that constitute our health, but it’s the behaviors and daily regimens that generally drive how sick we get, or even how often . There’s a point to be made that fighting over vaccines will be made moot if people on both sides of the discourse continue to eat poorly and stay indoors- both groups will be doomed to ill-health regardless.

And so I’ve thought about releasing occasional posts that focus on those aspects that we tend to overlook even though they are the greatest contributors to our overall health. First, I’ve decided to write a bit about sleep since there’s no doubt that people are not getting enough of it already. Eventually I’ll write about other issues such as weight, sunlight, and exercise and how they all factor into our wellbeing and health.

The Need for Sleep

Sleep. Sleep is one of those things that we fight against when we’re little, yet can’t seem to get enough of as we get older.

We’re expected to spend a third of our lives sleeping, and although this doesn’t seem like a good way to spend our time sleep is critical to our daily functions.

And yet it is when we sleep that our body carries out most of the biochemical processes needed to help us function every day1. Sleep is when memories are formed and reserved. Sleep is when many of the insults and toxins we accumulate throughout the day are dealt with. In fact, sleep is when many of our most critical immunological functions take place. In general, it is when we sleep that we usually heal.

We’re generally expected to get 7-9 hours of sleep on average every night, yet modernity and the stresses of daily life seem to have interrupted much of our sleep.

Whether it’s through additional work that pushes back our bedtimes, or whether it’s through constant exposure to blue light radiation that prevents proper accumulation of melatonin that keeps us up.

It actually may not be uncommon to hear someone suggest that sleep takes up time that could be used for other activities, even though sleep is critical for our overall health.

And even when we do get the intended levels of sleep, many people may not get what is considered “good” sleep- restful sleep that doesn’t leave one feeling groggy or reaching for a shot of espresso even though a full 8 hours were spent asleep.

In short, modern life continues to take up our time and ability to get a good night’s rest.

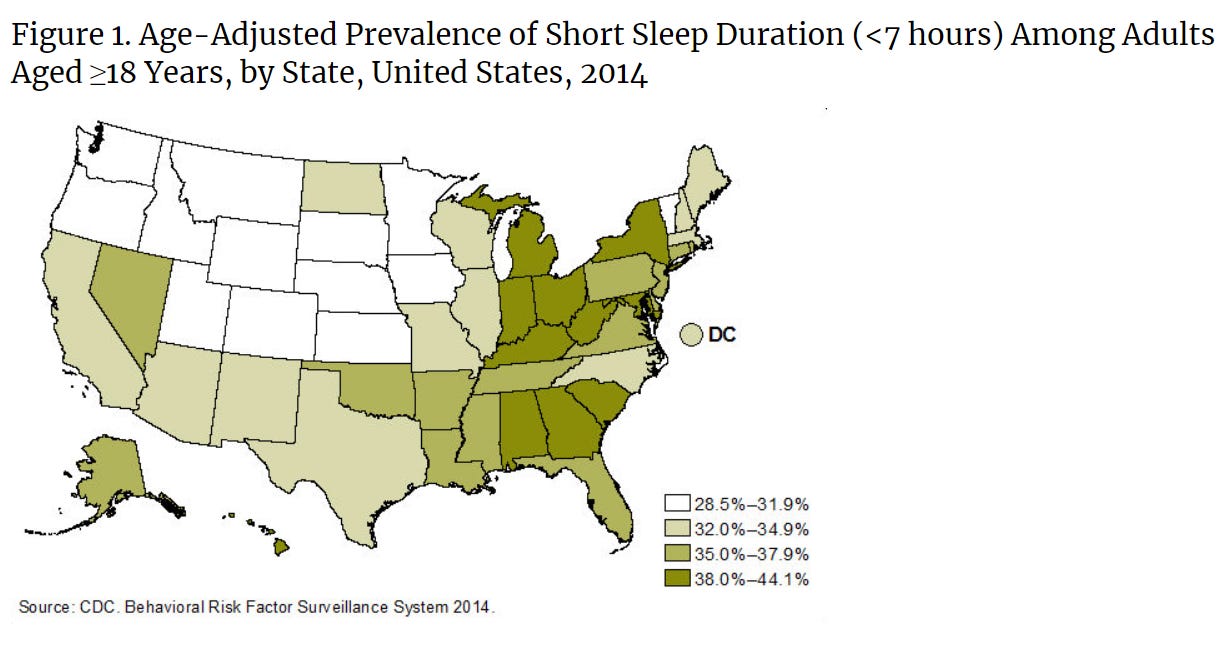

A 2014 survey conducted by the CDC showed that up to a third of Americans are getting fewer than 7 hours of sleep per night, a term referred to as short sleep duration.

And this number is expected to have grown significantly since the 2014 survey was conducted.

With the onset of the pandemic, it was expected that more people than ever before would suffer from lack of sleep, with a term eventually called “coronasomnia” being adopted in several news outlets.

The Sleep Foundation provides a definition of coronasomnia, as well as a mnemonic device that provides a few contributing factors to coronasomnia:

In essence, we have become more sleep deprived, more stressed, and less healthy overall as the stresses of modernity and the pandemic weigh heavily on many of us.

Less sleep; poorer health

Although many Americans consider sleep to be a pivotal contributor to their overall health, these Americans also appear to not understand the association between sleep and other risk factors and comorbidities, as indicated in several surveys such as this one from The Better Sleep Council2:

Lack of sleep has been associated with a ton of maladies, including cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and depression (Garbarino, et. al.3):

In addition to fatigue, excessive daytime sleepiness, and impaired cognitive and safety-related performance, sleep deprivation is associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes and all-cause mortality20–24. Indeed, epidemiological and experimental data support the association of sleep deprivation with the risk of cardiovascular (CV) (hypertension and coronary artery disease) and metabolic (obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2DM)) diseases24–27. In the United States, sleep deprivation has been linked to 5 of the top 15 leading causes of death including cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases, accidents, T2DM, and hypertension28. Data also point to a role for sleep deprivation in the risk of stroke, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs)26,29,30. Sleep deprivation is also associated with psychopathological and psychiatric disorders, including negative mood and mood regulation, psychosis, anxiety, suicidal behavior, and the risk for depression31–36. […]

Sleep profoundly affects endocrine, metabolic, and immune pathways, whose dysfunctions play a determinant role in the development and progression of chronic diseases42–44. Specifically, in many chronic diseases, a deregulated/exacerbated immune response shifts from repair/regulation towards unresolved inflammatory responses45.

One key contributing factor to these maladies is the inability for the body to properly address inflammation due to lack of sleep. Stressors accrued throughout the day may not properly be addressed with short sleep, and thus may carry over to the next day. Continuous lack of sleep may then lead to chronic inflammation with an end result of severe, chronic illness (Irwin, M.R.4):

In line with this notion, persistent sleep disturbance leads to sustained activation of the inflammatory response, which can be damaging to the host (Fig. 2). Chronic inflammation is widely recognized to have a role in several major diseases, including depression, certain cancers, cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer disease-associated dementia40. A similar profile of disease risk is found for sleep disturbance2,12, which suggests that inflammation is a plausible mechanistic link between sleep and risk of these diseases.

Chronic fatigue through lack of sleep may also contribute to memory loss and impaired attention, which may lead to increased rates of fatal car accidents. In general, all facets of our daily lives suffer when we don’t get enough sleep.

And lastly, lack of sleep appears to affect transcription factors of immune cells (Imeri, L. & Opp, M. R.):

As mentioned above, in contrast to the few reports of the effect of host-defence activation by endotoxin in humans, there have been numerous systematic studies in which human volunteers have been deprived of sleep and effects on immunity determined. The first study of the effects of sleep loss on immunity in humans seems to be that of Palmblad et al.106. They demonstrated that 48 h of sleep deprivation reduced phytohaemagglutinin-induced DNA synthesis in lymphocytes, an effect that persisted for 5 days. This study was followed by more than 50 other studies that showed effects of sleep deprivation on the human immune system. By way of example, 64 h sleep deprivation is associated with alterations in many aspects of immunity, including leukocytosis, increased natural killer cell activity and increased counts of white blood cells, granulocytes and monocytes107. According to recent reports, as little as 4 h of sleep loss in a controlled laboratory setting increases the production of interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor by monocytes — an effect that, bioinformatic analyses suggest, is mediated by the nuclear factor-κB inflammatory signalling pathway108.

So it is not just through sleep that we heal, but it is through lack of sleep that we may be doing detrimental harm to our own bodies.

Sleep and Immunity

There’s so much more to discuss in regards to sleep. However, given current events it may be important to focus on the role of sleep and immunity.

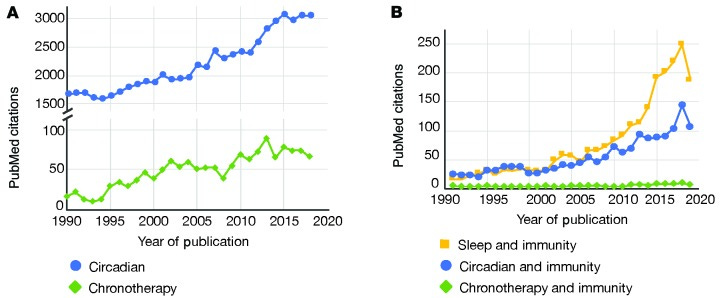

Sleep indeed has an association with our immune systems. In fact, research has been greatly increasing over the past few years in regards to the immune system, sleep, and our biological sleep/wake cycle called a circadian5 rhythm.

Growing interest has led to newly emerging fields such as chronotherapy, which takes advantage of circadian rhythms and biological processes to provide time-dependent treatment options (refer to Footnote 5), as well as neuroimmunology, which combines neurology, immunology, sleep and circadian rhythm to examine their relationships in regards to infections, autoimmune disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

So there appears to be a strong association between the need for sleep and a proper functioning immune system. We’ll go over a few factors and explain how sleep relates to our overall immunity.

Sleepy, Sleepy, Cytokines (Innate Immunity)

When we generally feel unwell, whether through coming down with an infection or fatigue through hard work, we may lean towards taking a nap or getting some rest. There’s an inherent function within our bodies to want to sleep when we don’t feel well.

But what exactly causes us to feel the need to sleep after accruing stressors?

Probably one of the most fascinating revelations is that cytokines, which are intrinsically involved with our innate immune system, may actually play a huge role in making us feel fatigued and sleepy6.

Cytokines are small proteins that are involved with a broad degree of cell signaling within our bodies, most notably with immunity and inflammation. We are made up of both pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines.

A more technical definition of cytokines is provided below (Zielinski, et. al.7):

Cytokines are small proteins molecules involved in cell signaling allowing cells to communicate through autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine mechanisms (61). Cytokines modulate immune responses, inflammation, cell growth and maturation, and normal physiological functions. They are highly conserved among species ranging from invertebrates to rodents and humans. Inflammatory cytokines are produced by nucleated cell types including lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as microglia, astrocytes, and neurons in the CNS (62).

Cytokines are generally released during an infection or after trauma to the body, such as through a wound. They are also released during chronic inflammation and may play a role in depression and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Although many cytokines are currently being researched for their roles in sleep, so far the cytokines Interleukin-1 (IL-1)8 and tumor-necrosis factor (TNF) have been found to be the most heavily associated with sleepiness.

It is within recent years that researchers have found receptors for IL-1 and TNF within the central nervous system, leading researchers to suspect that cytokines may alter our sleep/wake function (Imeri, L. & Opp, M.R.):

Neurons that are immunoreactive for IL‑1 and TNF are located in brain regions that are implicated in the regula‑tion of sleep–wake behaviour, notably the hypothalamus, the hippocampus and the brainstem24,27. Signalling recep‑tors for both IL‑1 and TNF are also present in several brain areas, such as the choroid plexus, the hippocampus, the hypothalamus, the brainstem and the cortex, and are expressed in both neurons and astrocytes22,28,29

Both IL-1 and TNF have shown to have several effects on sleep. For instance, higher levels of serum IL-1 and TNF have been associated with higher levels of non-rapid eye movement (NREM; non-REM) sleep, also considered the early stages of sleep. Animals and humans provided IL-1 and TNF antagonists also generally show impaired NREM sleep.

Because pro-inflammatory cytokines are released during the onset of an infection, it makes sense then that elevated levels of IL-1 and TNF may contribute to the tired feelings we get when we are sick. As an infection increases, additional IL-1 and TNF will be released by the body. Eventually, the levels may be too high that it influences sleep outside of typical time periods.

There could be valid evolutionary reasons for inducing sleep during an infection, to the point that sleepiness may be an adaptive response (Imeri, L. & Opp, M.R.)9:

How might infection‑induced alterations in sleep promote recovery? We propose that they facilitate the generation of fever. In this view it is fever that imparts survival value, and fever could not develop during infection if sleep architecture was not altered. This hypothesis is based on two extensive bodies of literature, one describing links between sleep and thermoregulation96 and the other indicating that fever is adaptive97

As proposed within the review article, fevers are heavily energy-dependent. In an attempt to bolster the production of fevers, the body may respond by decreasing biochemical activity during NREM sleep to direct towards fever production. Not much is known as to the full relationship between fevers and sleep, but research continues to advance the subject matter.

A Bit on Adaptive Immunity

Generally, the association between sleep and cytokines points towards the innate immune system.

Not much has been learned in regards to B and T cell memory in regards to circadian rhythms and sleep. Usually such arguments are anecdotal and relegated to results seen in sleep-deprived animals. Regardless, there does appear to be some relationship which future research may further elucidate (Haspel, et. al.10):

While there has been an intense focus on how clocks regulate innate immunity, research into the mechanisms connecting circadian and sleep disruption to adaptive immune functions remains sparse. This is partly due to early skepticism that something as short as a 24-hour clock could be relevant to antigen-specific B and T cell responses, which form over days to weeks. Results from prior experiments in mice with T cell–specific Bmal1 deletion were interpreted to mean that circadian clocks have little influence over adaptive immune activities (96). However, some of these earlier experiments did not factor time of day into the experimental design, and subsequent studies that controlled for this variable did report circadian effects in outcomes such as autoimmune pathology (56, 65). Moreover, T cell proliferation in response to antigen displays a circadian rhythm in mice that is clock dependent (97). In other research, time of day and sleep quantity were both shown to impact markers of vaccine efficacy in humans and rodents (44, 74, 75, 97–99). Clocks may also affect adaptive immunity via control of immune checkpoints, as disruption of circadian rhythms in rodents appears to exacerbate bacterial peritonitis in part by increasing programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on macrophages, which represses T cell activities (100).

Although the evidence for the effects of sleep on adaptive immune responses to infection are sparse, there’s no doubt that sleep overall plays a crucial role in immunity.

The Intersection of Sleep and Immunity

Sleep is one of our most crucial biological functions, and yet modernity and the daily stresses of life make it nearly impossible to get a good night’s rest.

It is when we are restful that we are at our best, and that speaks especially true for our immune system. Sleep deprivation is extremely detrimental to our health. It makes our immune systems weaker, it affects our faculties when we are awake, and it prevents us from being able to fight off infections adequately.

If we are to take care of our health and do what is important, we can’t overlook the significance that lack of sleep plays in our ability to fight off diseases.

Because this post rang long, the next one will include a few things to promote better sleep, as well as a questionnaire to ask a few questions about your sleep habits.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Even as significant of a function as sleep may be, there are still many gaps in the literature as to what specific role sleep plays. There’s much left to be elucidated in regards to sleep. This information from Bryant, et. al. provides a few hypotheses as to the purpose of sleep:

Bryant, P., Trinder, J. & Curtis, N. Sick and tired: does sleep have a vital role in the immune system?. Nat Rev Immunol 4, 457–467 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1369

This survey also suggests that many Americans are aware that they are not getting enough sleep, yet haven’t done anything to alleviate that problem.

Garbarino, S., Lanteri, P., Bragazzi, N. L., Magnavita, N., & Scoditti, E. (2021). Role of sleep deprivation in immune-related disease risk and outcomes. Communications biology, 4(1), 1304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02825-4

Irwin, M.R. Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health. Nat Rev Immunol 19, 702–715 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0190-z

“Circadian” refers to things with a period cycle of 24 hours. Nearly all of our biological processes undergo some form of periodicity. Not only do we as an organism have a sleep/wake cycle, but many of our cells have their own cycles. Some cells may only undergo replication during certain hours of the day. Some biochemical compounds may only be released in response to light, such as serotonin and melatonin.

There is some research examining how different cell cycles may be utilized for different treatments. For example, chemotherapies that target cancer tend to target other rapidly dividing cells. A few suggestions have been made that chemotherapies may be timed for when cancer cell division is generally high while other forms of cell division are generally low. Doing so may increase the effectiveness of these therapeutics while reducing their cytotoxic effects on other cells (citation below).

Sancar, A., Lindsey-Boltz, L. A., Gaddameedhi, S., Selby, C. P., Ye, R., Chiou, Y. Y., Kemp, M. G., Hu, J., Lee, J. H., & Ozturk, N. (2015). Circadian clock, cancer, and chemotherapy. Biochemistry, 54(2), 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi5007354

Compounds that make us sleepy are called somnogens (somno- latin for “sleep”, and gen referring to generator).

Zielinski, M. R., Systrom, D. M., & Rose, N. R. (2019). Fatigue, Sleep, and Autoimmune and Related Disorders. Frontiers in immunology, 10, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827

Imeri, L., Opp, M. How (and why) the immune system makes us sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci 10, 199–210 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2576

Haspel, J. A., Anafi, R., Brown, M. K., Cermakian, N., Depner, C., Desplats, P., Gelman, A. E., Haack, M., Jelic, S., Kim, B. S., Laposky, A. D., Lee, Y. C., Mongodin, E., Prather, A. A., Prendergast, B. J., Reardon, C., Shaw, A. C., Sengupta, S., Szentirmai, É., Thakkar, M., … Solt, L. A. (2020). Perfect timing: circadian rhythms, sleep, and immunity - an NIH workshop summary. JCI insight, 5(1), e131487. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.131487

I am all onboard with the "need for sleep". Slept for 10 hours this Saturday and could not be happier.

But in many ways, good sleep, important as it is, is kind of like "good love life". Is it important to have "good love life"? You bet! But it is not easy to have "good love life" even if one decides to have it -- it is hard to get.

Sleep is also like this, so many commitments, BS etc. I have to wake up at 5:45am during the week days. Even though I love my job, I hate waking up at 5:45. Even though I own my business I cannot change this. Now as for going to bed early, I often start writing something in the evening, or read stuff like your substack etc. Cannot go to bed at 9pm.

Not so easy to have good sleep, even though it is 100% extremely important!!

Anyway, knowing what you wrote, I will try harder!

Sleep is so important! Thanks for the reminder.