The Illusion of Evidence-Based Medicine is Nothing New

It’s only recently that more people have become aware

Science seems to have an apparent gleam of infallibility. It presupposes, based upon its name and subject alone an air of imperiousness that puts it above any form of criticism. Science, as it is presented, is taken as a consolidation of facts, evidence, and logic that allows science to be presented as a consensus of ideas.

However, this form of science can’t be further from the true principles of science. Ideally, scientific principles should always be under scrutiny, always willing to be open to correction, and always open to discourse and dissenting viewpoints. A science that presents itself as infallible is in no ways actual science.

The best example of this illusion is the concept of evidence-based medicine. The drugs we take are purported to have undergone rigorous testing procedures and scrutiny, with agencies such as the FDA and NIH serving as validations of these supposed rigorous standards. However, the rapid push for massive COVID vaccination has clearly indicated that what we considered to be stringent standards in medicine and science are not what they appear to be. Indeed, it’s become more apparent that such processes may be more of an illusion that an actual occurrence.

A recent article from the BMJ1 has made its rounds, arguing that many studies are captured by industrial and pharmaceutical interests, with the trickle-down effects making their way into academia.

It’s a short article that I recommend people read if they have not done so already. What’s interesting is that, although this article is extremely timely, it doesn’t present anything new. There’s always been evidence that medicine does not follow the procedural lines that we expect it to, but it’s only now that the public has become aware of such faults.

Facts vs Evidence

In a discussion about evidence-based medicine we may be surprised to find out that evidence and facts are not interchangeable terms.

Facts are information and knowledge that is considered to be irrefutable based on occurrences. Facts alone do not validate facts, but facts are actually validated by evidence.

Evidence is a set of results or indications that support a conclusion or fact. Therefore, it is the idea that evidence reaches a consensus that we can state something as being factual. The existence of gravity is factual, but the concept of gravity draws from numerous studies that provide evidence of its existence. In essence, evidence begets facts.

But what happens when the evidence that we see is not indicative of the totality of evidence? We’ll explore this question further down, but there’s this false assumption that the evidence that we are presented with is indicative of all of the evidence available.

Take, for instance, all of this talk surrounding Ivermectin. As soon as one study provides evidence against Ivermectin’s effectiveness, people are quick to take these results as factual and argue that this means Ivermectin does not work against COVID. The same can be said when a study comes out suggesting that Ivermectin is effective. Under both circumstances people are quick to take both studies as evidence that supports a fact. Yet rarely do people view these studies in the overall concept of all Ivermectin studies. It is the entirety of these studies and the evidence they provide that allows us to argue the factual basis of Ivermectin’s effectiveness.

Antidepressants: A case of Evidence-B(i)ased Medicine*

*Credit to Dr. Pandiyan Natarajan within the comment section of the BMJ article for coming up with this clever name.

It is the basis of evidence where many pharmaceutical studies can alter the factual representation of drugs, and no better example exists than the world of antidepressants.

As concerns over mental health gain in prominence, so too are therapeutics intended to treat the increase in mental health diagnoses. Concerns are increasing over the increase in depression and anxiety among many, including the young, after two years of COVID hysteria.

But the world of antidepressants has always been considered a prime representation of publication bias.

Let’s pretend that you are a company designing a brand new antidepressant. In order to test the effectiveness you conduct 6 Clinical trials. The end results of these studies suggest that 2 studies showed benefits, 2 showed no benefit, and 2 showed a worsening outcome of the new antidepressant group.

If we were to consider the evidence above in simplistic terms, we may consider that this new antidepressant is not effective and should not be brought to market as the totality of the evidence argues against such a feat.

However, what if only the two positive studies and one “no benefit” study was reported? Well, we would only be able to evaluate the effectiveness of this new antidepressant based on these 3 studies, which may mislead us into believing that this drug is effective. In this case the evidence would argue in favor of the drug.

Although this is a hypothetical scenario, this occurs far too often and is actually a common practice when it comes to antidepressants. As stated above, many drugs suffer from a bias called publication bias where only positive results tend to get reported and negative/null results are either under reported or not reported at all.

A good supplement to the BMJ article is this article from Joober et. al.2, and this excerpt in particular is very telling:

Publication bias has an escalating and damaging effect on the integrity of knowledge. The research process usually starts by conjecturing a relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable, and the purpose of hypothesis testing is to determine how the belief in the relationship will change compared with its a priori credibility. This a priori credibility is constructed on the basis of an analysis of the available literature. When published, the results of this testing should contribute to an unbiased update of the credibility of the relationship. In the presence of publication bias, belief in the relationship increases artificially and iteratively with each positive publication. This, in turn, diminishes the credibility of hypothesis testing because it is based on biased information, and calls into question the integrity of the entire experimental framework.

Poor evidence, when first introduced, may taint further evidence down the line. Positive results of a new drug, when done under false pretenses with negative results hidden, may cause researchers to wrongly assume the effectiveness of said new drug. Further research may search for additional positive results, and if the results end up negative researchers may falsely assume it is an exception to the overwhelmingly positive results, and in certain instances may not report said findings.

Take, for example this TED talk from Dr. Ben Goldacre who wrote the book Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients who succinctly summarizes many of the issues with how studies are conducted. It’s a video from 2012 and yet is even more pertinent today. (Note: Pay attention to the manufacturer of one of the antidepressants).

One of the studies Dr. Goldacre brings up is this pivotal study by Turner et. al.3 that was published within the NEJM in 2008 in which the researchers found that clinical trials with positive outcomes were more likely to be published than clinical trials with either no or negative benefit:

Among 74 FDA-registered studies, 31%, accounting for 3449 study participants, were not published. Whether and how the studies were published were associated with the study outcome. A total of 37 studies viewed by the FDA as having positive results were published; 1 study viewed as positive was not published. Studies viewed by the FDA as having negative or questionable results were, with 3 exceptions, either not published (22 studies) or published in a way that, in our opinion, conveyed a positive outcome (11 studies). According to the published literature, it appeared that 94% of the trials conducted were positive. By contrast, the FDA analysis showed that 51% were positive. Separate meta-analyses of the FDA and journal data sets showed that the increase in effect size ranged from 11 to 69% for individual drugs and was 32% overall.

Keep in mind that this study examined registered clinical trials between 1987 and 2006 which reflects the regulatory processes of the time. Nonetheless, it’s quite telling that such a discrepancy between reported results and missing results depends largely upon the positive results of said clinical trials.

The authors of the study concluded that:

We found a bias toward the publication of positive results. Not only were positive results more likely to be published, but studies that were not positive, in our opinion, were often published in a way that conveyed a positive outcome. We analyzed these data in terms of the proportion of positive studies and in terms of the effect size associated with drug treatment. Using both approaches, we found that the efficacy of this drug class is less than would be gleaned from an examination of the published literature alone. According to the published literature, the results of nearly all of the trials of antidepressants were positive. In contrast, FDA analysis of the trial data showed that roughly half of the trials had positive results. The statistical significance of a study's results was strongly associated with whether and how they were reported, and the association was independent of sample size. The study outcome also affected the chances that the data from a participant would be published. As a result of selective reporting, the published literature conveyed an effect size nearly one third larger than the effect size derived from the FDA data.

So it was quite evident, even from a few years prior, that biases were always part of the reporting process of many drugs, although it was less likely to be within the public eye at the time. Most of these studies may not be accessible to the layperson and thus they may not be able to discern for themselves whether there is any validity to a clinical trial or not.

Aducanumab: The Accelerated, Highly Controversial Alzheimer’s Drug

In an attempt to push for quicker therapeutics and vaccines against COVID many of the typical regulatory processes were bypassed for accelerated approval. However, at the same time we are criticizing these new vaccines, PAXLOVID, or Molnupiravir another drug, one not for COVID, underwent the same accelerated approval process.

One of the first drugs I wrote about was a monoclonal antibody called Aduhelm (generic name Aducanumab) and was developed by Biogen. It’s a monoclonal designed to target the amyloid plaques that form during Alzheimer’s dementia and is intended to be used in early phases of the disease in order to reduce disease progression. The drug gained fast-tracked approval in June of 2021 making it the first disease modifying drug against Alzheimer’s to be approved. The approval was highly controversial but was likely underscored due to the controversies surrounding the vaccines and likely helped to take some of the heat off of Aducanumab.

Aduhelm has been mired in controversies, with a quick list of some below:

The two Phase III clinical trials (ENGAGE and EMERGE) were abruptly ended due to futility as the preliminary results did not show that the drug would meet its primary outcome. However, Biogen reexamined the data and found positive outcomes in one trial (not the other) with high dose ADU suggesting improved cognition. Biogen would use such results for fast-tracked approval which raised questions about the veracity of the data.4

The amyloid plaque hypothesis for Alzheimer’s is controversial:5 are the plaques themselves the cause for dementia, or are they a symptom of the neurodegenerative process in general? And if the plaques are removed should there be an expectation that cognition would improve? This is apparently a highly controversial argument which adds more ambiguity to the actual effectiveness of Aduhelm.

Even with such such controversial results the FDA voted on fast-tracked approval citing the importance and urgency for a therapeutic agent (sound familiar?) to fight against dementia, even though nearly every member of the advisory committee rejected the approval.

The approval was seen as so controversial that 3 members of the FDA advisory committee resigned, with one (Dr. Aaron Kesselheim) writing a letter calling this approval “probably the worst drug approval decision in recent US history”.

The annual cost of the drug was estimated to be around $56,000, but because insurers were unwilling to cover the costs Biogen dropped the cost down to $28,000. As a frame of reference the median household income in the US in 2019 was $65,712.

The EU’s regulatory commission the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recently voted against bringing Aduhelm to the European market due to lack of efficacy and concerning adverse events.

Based upon brain scans of patients on Aduhelm roughly 41% of patients were reported to have amyloid-related imaging abnormalities events (ARIA-E) such as brain bleeds and swelling. Some are argued to be “mild” and easily treatable (again, sound familiar?). However, in November of 2021 Biogen began investigating the death of one 75-year old patient prescribed Aduhelm. Based upon the FDA’s adverse event reporting system (FAERS) there’s 3 suspected deaths from Aduhelm, although Biogen is contributing these deaths to other factors.

In light of everything going on in regards to these COVID vaccines this may come as no surprise, although the circumstances surrounding Aduhelm aren’t any different than the ones we are seeing with the mRNA vaccines. However, what’s concerning about Aduhelm is that it was the first fast-tracked drug not related to COVID, which raises questions as to whether this is likely to occur more frequently within the coming future. The parallels between Aduhelm and Molnupiravir suggest that this is not a circumstance of COVID but may be a circumstance of the fast-tracked policies that have been adopted in general. The sense of urgency guiding policies is all too common now- we can look at green energy policies as an example of that, especially with rising gas prices- and COVID has certainly paved the way to allow for more accelerated approval of other drugs under the pretense of urgency.

But what’s more concerning is that the approval of Aduhelm was the epitome of going against evidence-based medicine. The evidence clearly suggest that Aduhelm was not effective and may lead to adverse events, and even with an overwhelming majority of the advisory committee members voting against the approval the FDA still decided to fast-track the approval- all under the guise of urgency.

As noted in the CNN article6 it appears that Aduhelm was indicative of regulatory capture; the FDA, instead of working separate that of Biogen, appears to have been working alongside Biogen in getting approval of Aduhelm. Essentially, the approval was inevitable:

The question, then, is what happened between April and June, when the drug was approved, to turn things around. To Dr. Michael Carome, a physician who is the director of the Health Research Group for the consumer advocacy nonprofit Public Citizen, which has long been critical of the FDA, the reason for the agency's action can be summed up by the phenomenon known as regulatory capture, that is, the pharmaceutical industry has effectively taken control of the part of the government that is supposed to regulate it.

"We believe that the FDA, starting back in 2019, worked in inappropriately close collaboration with Biogen," said Carome, who testified at the advisory committee meeting against FDA approval of Aduhelm. "FDA became a partner with Biogen, and they made the decision about whether to approve the drug. They were not objective, unbiased regulators. It seems as if the decision was preordained."

We do have to take such commentary with a grain of salt, but at the same time this may not be seen as a surprise. Regulatory/institutional capture is more than expected and the COVID vaccine approval does not help to assuage any criticisms or concerns.

So in short, just as we are concerned about the approval and regulatory processes involved with the COVID vaccines and therapeutics, be fully aware that other drugs have been, and may be fast-tracked within the near future.

Is there Hope for Improvement?

Maybe some of us may not feel so optimistic, and in some instances we may expect that the worst is yet to come. However, not all hope is lost.

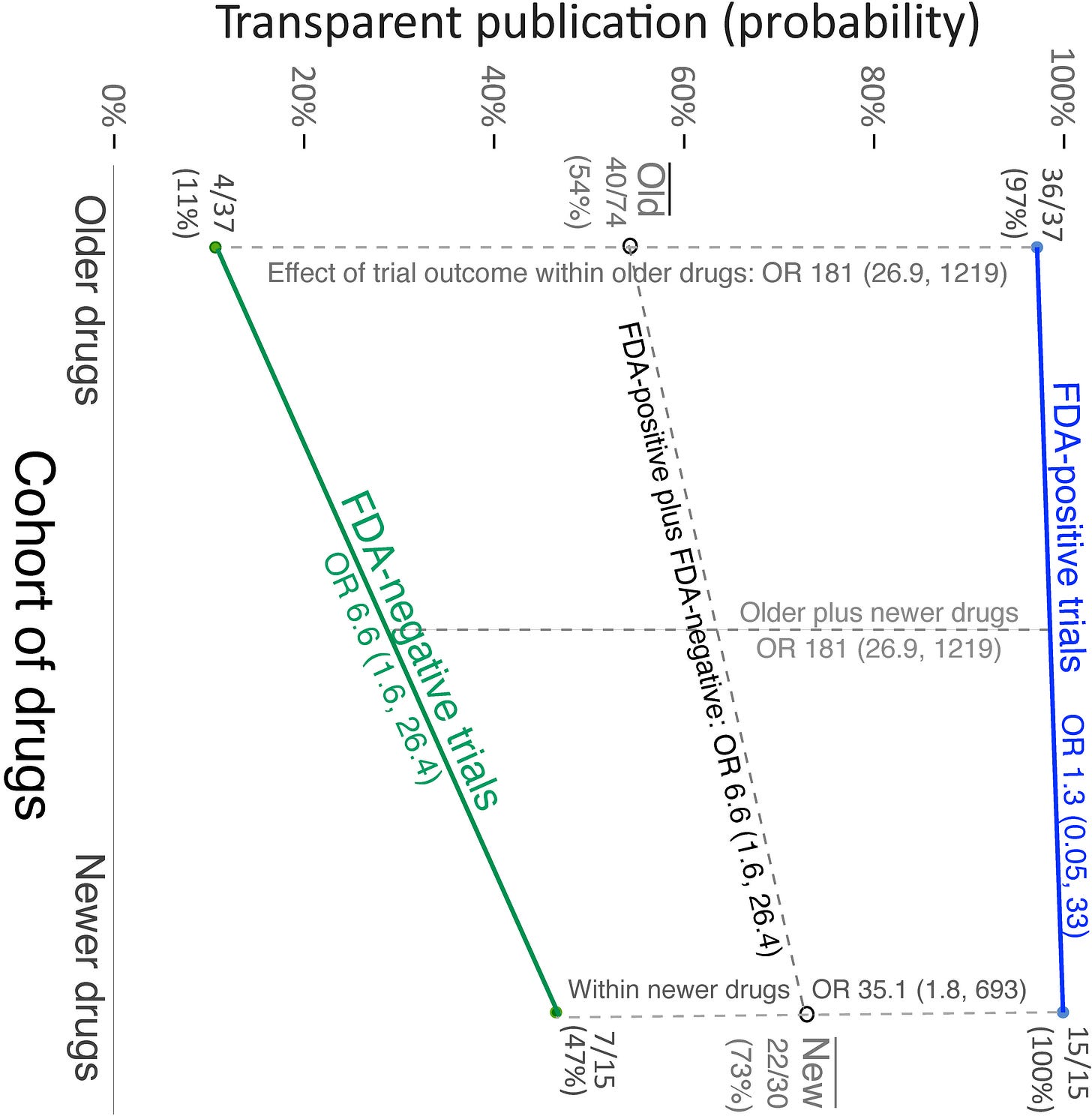

The same team that conducted the 2008 study in regards to publication bias released another recent study7 in which 30 studies of 4 antidepressants were examined for publication bias. This study looked at published studies between February 2008 and September 2013 and compared these results to those form their prior study. The results seem promising, and suggest an improvement from 11% reporting of negative results to 47%. I also suggest people read a related article that has similar sentiments.8

This study provides some perspective in that it at least suggests that publication bias may be improving and pharmaceutical manufacturers are becoming more transparent, although the concerns still persist. It begs the question: even if publication bias is getting better, at what point would it be considered “good enough”?

As to why transparency may be improving, the researchers provide an explanation:

How might we explain this apparent increase in transparency? There have long been many incentives to engage in reporting bias [36]. In the past, there was little awareness within the research and clinical communities that the problem existed, and pharmaceutical companies (and others) could engage in reporting bias without fear of detection. Since then, however, there has been a cultural change, and what was once standard practice is no longer considered acceptable. Numerous policy changes have been implemented, summarized elsewhere [37]. ClinicalTrials.gov was launched in 2000, but registrations initially lagged. In 2004—the year the FDA approved duloxetine, the newest drug within the older cohort of antidepressants [2]—the International Committee of Journal Editors (ICMJE) announced that prospective registration would be a precondition for publication. The following year saw a 73% increase in the registration rate over a span of just 5 months [38]. In 2005, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) was launched. In 2007, the FDAAA was enacted [13], which legally mandated public registration of applicable clinical trials and called for the augmentation of ClinicalTrials.gov with a basic results database; in 2010, FDAAA was clarified and expanded in scope to include all Phase II to IV drug and device trials, adverse events, and basic results [39].

It seems reasonable to conclude that these policy changes played a major role in bringing about the increase in transparency suggested by the current study and the others mentioned above. However, given the level of attention directed toward reporting bias with antidepressants, in the form of lawsuits [39], numerous key publications [2,40–43], and new incentives to increase transparency, for instance, the Good Pharma Scorecard [31], it is possible that substantial improvement would have occurred without these policy changes.

So it appears that public perception may play a big role in transparency. If more people become aware of the faults of reporting, more pressure can be placed on pharmaceutical companies to accurately and transparently report their results.

Transparency faces many challenges and the possible increase in the accelerated process raises many concerns. However, at the same time we should note that an informed populace may serve as the crux of enforcing more regulation and hold both the FDA and pharmaceutical companies to account. The ongoing debate with these COVID vaccines, with possible future lawsuits are helping to shine greater light onto the process that originally would not have been available. Open-access to studies have allowed people who would have been naïve to regulatory capture a window into the how the sausage is made, and for many they are not happy with what they see. This is the main reason we are seeing such activism, as we as pushback in regards to mandatory vaccination.

So here are some things to consider:

Publication Bias and Institutional Capture is nothing new. What we are seeing now is not something that is occurring because of COVID. Many of these forms of capture and bias have been around for several decades. Funding by pharmaceutical companies can be traced back to the early 90s, and for decades several professors and regulators have had close ties to many in the industry and have influenced approval and recommendations.

COVID granted the public a glimpse into how the sausage is made. Before COVID most may have been naïve to how clinical trials are conducted. However, open-access to hundreds of COVID studies has provided the public an opportunity to see the review and scientific process play out in real time, and in most cases what can be seen is not something most would approve of. Nonetheless, the ability to see into the window and actively know what is happening is why such a large pushback is possible. There would be no need for massive “misinformation” campaigns if the pushback wasn’t so fervent in nature- the Canadian Trucker Convoy and the release of Pfizer’s documents are proof of that. So although there is much to be upset about, there is still much to be optimistic about. Transparency is closely tied to public pressure, and the more the public pushes for accountability and transparency the more we can hope that this will occur.

Research should encourage the publication of negative/null studies. The standard process of approval overwhelmingly supports positive results, meaning that negative or null results go unreported. However, evidence-based medicine is based upon the totality of evidence, not the selection of favorable evidence. Therefore, it is extremely imperative that more results get published, not fewer.

More transparency is needed. Institutional and regulatory capture are guided by conflicts of interest. If pharmaceutical companies are able to pay their way into advisory committees then we should expect that these committees will inherently benefit the pharmaceutical industry. Researchers that accept grant money or support from drug manufacturers should be more transparent about these biases and conflicts of interest. Regulatory agencies such as the FDA and NIH should be heavily discouraged from seeking funding from drug manufacturers, and if done it must be done in a manner that reduces influence on advisory and approval of drugs.

There is always room for hope. As melancholic as the future may seem, there is always room for a little bit of optimism. There appears to be some evidence that publication bias may be decreasing. Although it may not be to the degree we would hope, it’s a start and hopefully the beginning of a more transparent era of research.

Jureidini J, McHenry L B. The illusion of evidence based medicine BMJ 2022; 376 :o702 doi:10.1136/bmj.o702

Joober, R., Schmitz, N., Annable, L., & Boksa, P. (2012). Publication bias: what are the challenges and can they be overcome?. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 37(3), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.120065

Turner, E. H., Matthews, A. M., Linardatos, E., Tell, R. A., & Rosenthal, R. (2008). Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. The New England journal of medicine, 358(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa065779

Knopman, DS, Jones, D, Greicius, MD. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimer's Dement. 2021; 17: 696– 701. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12213

Tagliavini, F., Tiraboschi, P. & Federico, A. Alzheimer’s disease: the controversial approval of Aducanumab. Neurol Sci 42, 3069–3070 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05497-4

It’s quite ironic that the CNN article is so close yet still hits the mark in some aspects. Even though the journalist drew parallels to the COVID vaccines, this was seen as a possible positive. Ironic that the article raises questions about regulatory capture in regards to Biogen and the FDA yet not to the same level as Pfizer/Moderna and the FDA.

Turner EH, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, de Vries YA (2022) Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy: Updated comparisons and meta-analyses of newer versus older trials. PLoS Med 19(1): e1003886. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003886

Mitra-Majumdar M, Kesselheim AS (2022) Reporting bias in clinical trials: Progress toward transparency and next steps. PLoS Med 19(1): e1003894. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003894

An excellent article. Thank you.

So, just sayin'. We live in a fascist police state. This is what one expects when the government and its agencies are captured by corporate interests. Corporate interest trumps the interest of people (no pun intended). Until I accepted this point of view, I was unable to understand "how this could happen". Another way of framing it is this: "why does a dog lick its ass?"

Aloha y'all