The codependent life of figs and fig wasps.

When mutualism between flowers and pollinators gets taken to the extreme.

In following Wednesday’s post this one will take a look at the lives of fig wasps and the obligate mutualism they display with figs.

For the Pollinators!

Modern Discontent is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Yes, that’s right: it’s pollinators week! Didn’t know that w…

“I can’t quit you”- The obligate lives of figs and fig wasps

Previously we looked a bit into some mutualistic interactions between flowers and pollinators, which are generally done with the benefit of each species, albeit for selfish interests.

However, what happens when this mutualistic relationship veers too far into codependency territory, to the point that neither species can exist without the other?

This is the case with figs and fig wasps, where it has been found that this mutualistic relationship is more one of obligation- essentially, many figs would die off without fig wasps, and fig wasps would die off without figs.

There are an estimated 750 fig species in the world, with the most common one being Ficus carica, or “common fig” as it is called. F. carica is native to regions of Asia as well as the Mediterranean, and it’s one of the most widely consumed figs, hence why we tend to use the overarching term “fig” when referring to this species in particular.

Some articles appear to suggest that the ratio of figs to fig wasps are nearly 1:1, and are suggestive that only one fig wasp species can pollinate one fig species. This doesn’t appear to be the case, as many fig wasp species seem to be capable of pollinating several figs, with some estimates suggesting fig wasps counts in the thousands relative to the hundreds of figs estimated to be found worldwide.

I’ll admit that I am acting a bit selfish in writing about figs since I have a fig tree. Unlike the wild blackberries that grow in my area, which are tart on top of tart on top of lip-imploding tart, figs never disappoint in their sweetness, and fig trees are extremely generous in their bounties. Unfortunately, this also means that various birds, beetles, and buzzing insects will begin visiting your fig tree to partake in the bounties as well.

The fruits of figs are interesting, as they don’t outwardly present flowers and seeds. Rather, the sex organs of figs are encased within slightly hollow bodies called syconium.

Many fig species are dioecious, and so each tree either displays male figs or female figs: capri figs, or male figs, display shorter flowers; female figs display longer flowers and are called edible figs as these are the figs we tend to eat.

If you consider the structure of a syconium, you may wonder how a fig wasp pollinates such a structure.

The answer lies in the bottom of the syconium, which contains an opening into the middle of the fig called an ostiole, and it’s here where the tragic and short life cycle of the fig wasp takes place.

The life of a fig wasp

Fig wasps don’t have much of an exciting life, and in fact the life of a fig wasp can be considered rather depressing. A fig wasp’s life boils down to escaping one fig, finding another fig, laying eggs, and…dying. Well, at least for the female fig wasps, as the male wasps die within the figs that they are born.

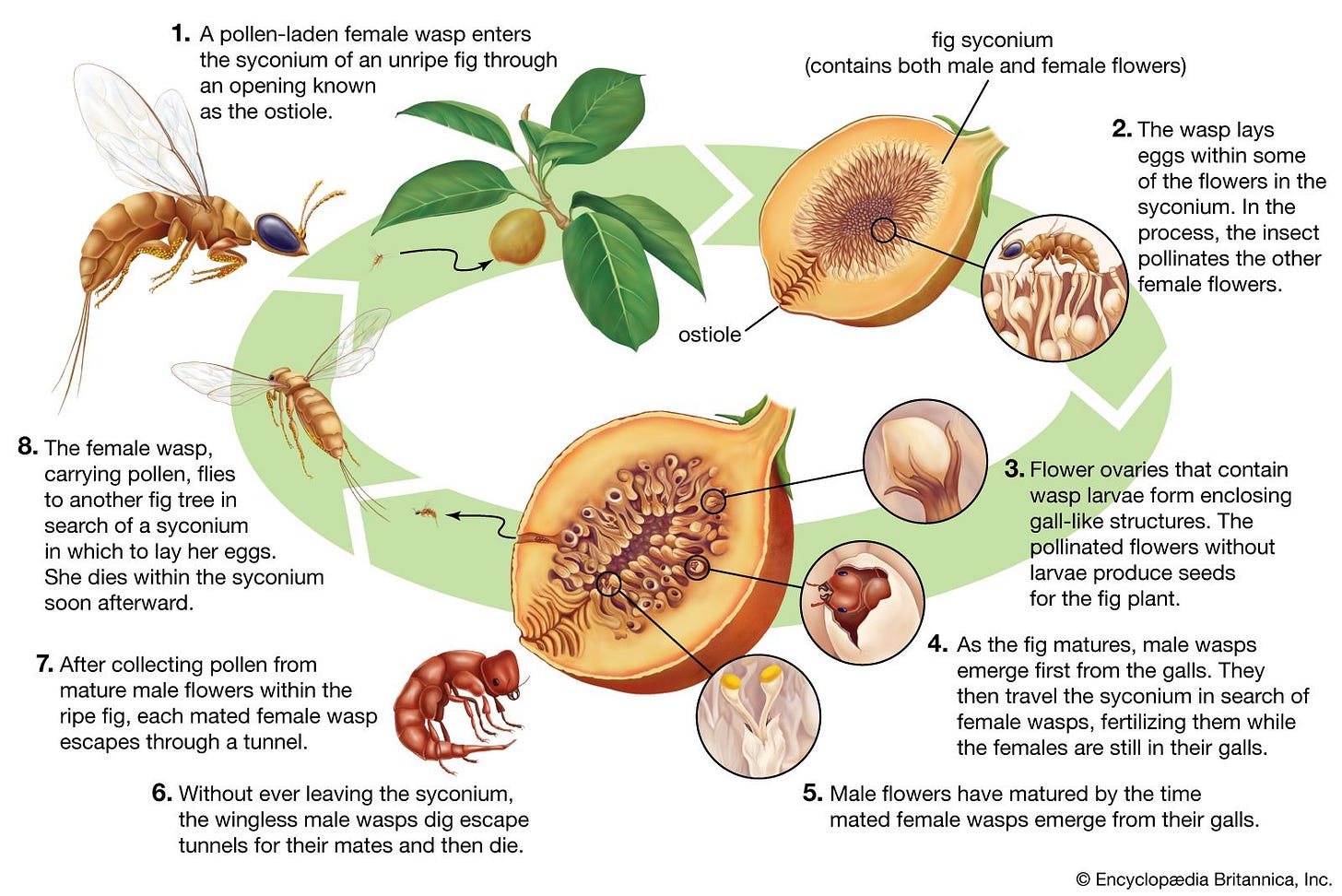

Encyclopedia Britannica provides an outline of this life cycle, as shown below:

Let’s suppose we start from the position of a female wasp escaping a fig.

A female fig escapes from a fig, covered in pollen collected from the escape, and goes in search of other figs to lay her eggs. The female wasps at this point are already impregnated, as the blind, male wasps that are hatched in the old fig readily impregnate their sisters.

It’s a rather tight existence, with each fig filled with many male and female fig wasps.

But as we follow a female fig wasp, she may come across an ostiole and decides to make her way inside. The path into the center of the syconium is tight, and in fact so tight that the female wasp’s wings and antennae may be ripped off. This is a one-way trip for the female wasp, as she is destined to die within the syconium she crawls into.

Now, depending on the fig species and whether they are dioecious or monoecious, different pathways are likely to occur.

Let’s consider the common fig which is dioecious. For a female fig wasp, the intent is to crawl into a capri (male) fig where she is capable of laying eggs and continuing her species.

However, if she instead enters into an edible (female) fig, the ending is more grim. She’s not capable of laying eggs here, and even if she does the eggs are likely to not produce offspring. Essentially, her attempts will be fruitless, and she will be doomed to death without bearing any viable offspring.

This appears to be intentional on the part of the female fig tree, as the edible figs appear to produce attractants similar to that of capris figs. This allows these figs to be pollinated, but don’t allow fig wasps to lay eggs.

The rest of the fig wasp’s life cycle is rather unremarkable. The male fig wasps that are born are doomed to death within the syconium that served as their birth place, serving only to impregnate the female fig wasps and to create holes in the figs for the female wasps to escape from. The only excitement may come in fig wasp species with a lower proportion of female wasps relative to male wasps. In this case, male fig wasps may compete and behead one another due to limited females.

And thus, the rather sad life of a fig wasp is shown. The female, by way of laying her eggs within the fig, also pollinate the fig. Some of the flowers are used to host the wasp eggs, forming a structure called a gall. The flowers that are not made to hold eggs are likely to be pollinated.

So… about that figgy crunch…

Now, you may have heard some stories online about figs, and given the information laid out here one may question whether the figs we eat are filled with wasps and eggs- this is actually one of the reasons I became rather curious of figs to begin with.

The answer is, it depends, and it depends on what figs you eat. In general, many of the figs we eat are likely to be the common fig, which are dioecious. Essentially, nature has separated the figs we eat from the figs that act as homes for fig wasps. There may be the off-chance that a female fig wasp enters an edible fig and dies, but the result of this accident is not all-too clear. Some articles appear to suggest that the fig wasp body is essentially disposed of, digested by the fig and consumed for nutrients. In that case, the edible fig likely does away with any traces of the female fig wasp. The fig also may be disposed of by the tree by releasing the fig.

Overall, the risk of eating an actual fig wasp is relatively low unless one consumes a monoecious species, so just take those little snaps as biting into a fig seed and not a wasp.

What’s also interesting is that not all figs appear to rely on fig wasps, as some species appear to self-pollinate. In any case, the relationship between figs and fig wasps is a fascinating one, and it displays what happens with the relationship between a flower and a pollinator become a bit too codependent.

For those interested

For anyone looking for more information on figs or this mutualism, I have included a few resources. Note that I’ve sampled from some of these places, especially the Cell article below, and some I briefly perused so I’m not fully aware of what some of these articles contain:

Dunn, D. W.1: Stability in fig tree–fig wasp mutualisms: how to be a cooperative fig wasp

Mawa, et al.2: Ficus carica L. (Moraceae): Phytochemistry, Traditional Uses and Biological Activities.

Cook, J. M., & West, S. A.3: Figs and fig wasps.

Machado, et al.4: Critical review of host specificity and its coevolutionary implications in the fig/fig-wasp mutualism.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Derek W Dunn, Stability in fig tree–fig wasp mutualisms: how to be a cooperative fig wasp, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 130, Issue 1, May 2020, Pages 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blaa027

Mawa, S., Husain, K., & Jantan, I. (2013). Ficus carica L. (Moraceae): Phytochemistry, Traditional Uses and Biological Activities. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2013, 974256. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/974256

Cook, J. M., & West, S. A. (2005). Figs and fig wasps. Current biology : CB, 15(24), R978–R980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.057

Machado, C. A., Robbins, N., Gilbert, M. T., & Herre, E. A. (2005). Critical review of host specificity and its coevolutionary implications in the fig/fig-wasp mutualism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 6558–6565. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0501840102

Very interesting! Nature is really amazing. So, if there were no more fig wasps, would figs just die out or do other pollinators ever come into play?

Thank you for this timely article. We are new to fig tree growing.

While we had very few figs on our two trees last year. Only one had started to produce any at all this year and these were quickly taken by the birds.

Next doors solitary fig tree, of many years, produces an abundance of beautiful figs. Which they vigorously prune every few years in order to encourage a plentiful harvest the following year.

Thank goodness for our neighbours who share their bounty with use because I love figs!