The Bursting of the Sterility Bubble

Attempts at sterility have likely harmed our microbiome and made us more susceptible to diseases.

The messaging this holiday season has inched ever closer to the return of mask mandates and further isolationist policies.

Recently, it’s been reported that schools in the UK are bringing back COVID-style bubbles as well as masks to curb Strep A infections.

The Telegraph notes the following actions taken by a few schools:

Parents at Costessey Primary School in Norwich were told there would be no mixing between year groups during breaks and lunchtimes from Friday after 17 cases of scarlet fever - a disease caused by Strep A - were confirmed within the school.

[…]

At Holmewood House Prep School, a private school in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, face masks have been made available for staff and children who would like to wear one and hand sanitiser has been made available in classrooms and other areas such as the dining hall.

The school has said it will keep doors and windows open during carol services and assemblies to increase ventilation, despite the cold weather.

The use of “bubble” here is rather broad. It doesn’t appear that the ridiculous screens and barriers used to surround individual children are reappearing, and fortunately several people have commented that “bubbles” have never been used prior to COVID and there’s no evidence that such measures will work.

Nonetheless, that hasn’t stopped many places from attempting to bring back the measures that have never been based on robust evidence showing that such measures actually work, as I noted in a recent post.

Across the US several states and counties are encouraging masking, and the CDC has now begun urging people to wear masks indoors, which is a change from last week when the comments were to “encourage” masking based on reports of Rochelle Walensky’s phone call to reporters.

Aside from the masking hysteria, the notion of such social bubbles and use of hand sanitizers reflect an understated issue of achieving sterility. It’s an idea that the only thing that needs to be eradicated are these respiratory pathogens without even considering all of the beneficial bacteria that are sacrificed for the cause of sterility.

Indeed, the long term, chronic use of hand sanitizers, soap, bleach, and disinfectant wipes are removing many of the microbes that help aid us in our well being.

Our microbiome, which is a system of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, as well as all of their genes that reside within all of us, all contribute to our overall health.

Many of these microbes are beneficial, with many producing some of the biological precursors and vitamins that we cannot produce ourselves. They also aid in our immune system, and likely contribute to how we deal with harmful pathogens.

Some of these microbes are also pathobionts, meaning that they may become harmful if certain factors are met that allow them to increase in number and possibly colonize different regions of the body.

When we use indiscriminate cleaning products we are inherently causing damage to our beneficial microbes; wiping them away not only eliminates the bacteria we need but also creates space for other bacteria to take over, such as pathobionts or pathogens that may harm us.

This notion that modern practices, in particular attempts to maintain sterile environments, may make our immune systems weaker by harming our microbiome is referred to as the hygiene hypothesis. It’s generally used to argue that rural children experience far fewer allergies and illnesses relative to children in urban settings, likely owed to the bacteria that they are constantly exposed to in younger years that help strengthen their immune system making it antifragile.

However, it’s not just incessant cleanliness that is detrimental, but many modern factors contribute to this negative alteration of microbes referred to as dysbiosis. Poor eating, sleeping, and medications all can alter our microbiome making us more susceptible to infection.

In essence, everything that was done under the guise of limiting the spread of SARS-COV2 has likely had a very detrimental effect on our microbiome, and therefore our health.

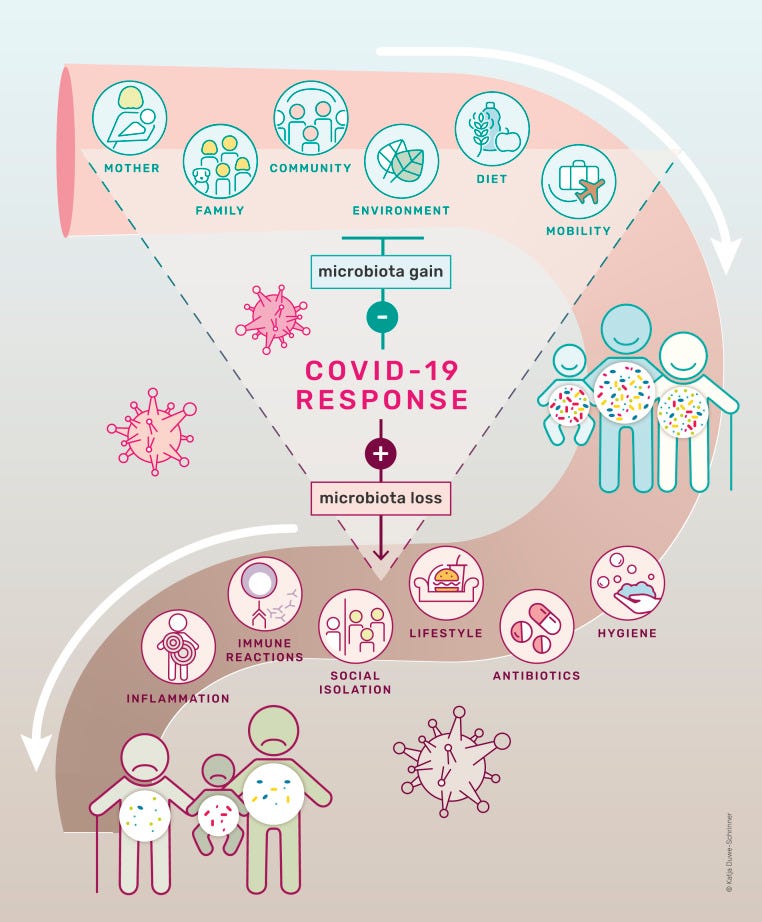

This is captured very well in this figure from Finlay, et al.1, which highlights how many of the measures taken over the past 3 years have likely altered our microbiome for the worse, causing our immune systems to suffer.

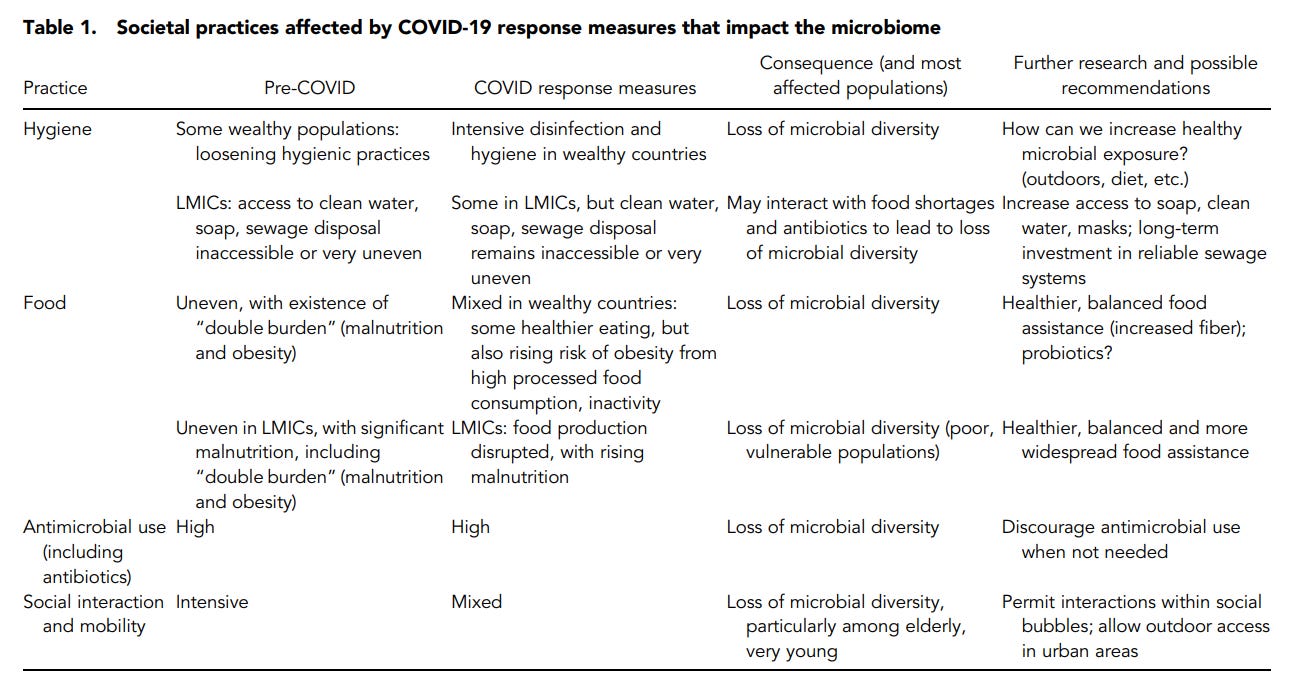

And is also listed in the following table:

It’s not as if modernity has not already altered the diversity of microbes. As noted in the Finlay, et al. review our microbiome has possibly been on the decline in recent decades:

Humans are at a major crossroads of two major biosocial processes affecting the microbes that collectively inhabit us (our microbiome). The first process is the continued loss of gut microbial diversity and ancestral microbes among a large swath of the world’s population. This loss of diversity has accelerated over the past several decades, likely affecting the coexistence between humans and our microbial residents and human health through the development of noncommunicable diseases, including obesity, asthma, cardiovascular diseases, and brain diseases (1). The second process, the COVID-19 pandemic, is occurring at a breakneck pace across the planet, with diverse consequences for its populations. Large-scale pandemics entail widespread pathogen transfer between individuals and disruption of human activity, and they presumably affect microbial diversity and richness in infected and uninfected individuals. The interaction of these two processes is of critical importance for the collective human microbiome and, more broadly, for human health.

Further evidence would be needed to support this claim.

However, consequently there have been some hypotheses and recent evidence alluding to the fact that removal of parasites such as helminths may have played a factor in allergies, as helminths may help modulate the immune system and reduce autoimmune responses, and may be a reason for the increased rate of asthma and allergic reactions seen in the WEIRD world.2

Therefore, it’s not hard to argue that modern perspectives would result in decreased diversity of microbes.

Rethinking Sterility

With respect to hygiene, the implementation of constant cleanliness may lead to downstream complications with other diseases:

Implementing much stricter hygienic practices now to contain COVID-19 transmission is necessary, but increased hygiene may come at a microbial cost by decreasing microbial acquisition and reinoculation following loss, although that cost is not yet known. For wealthier populations that can strictly adhere to hygienic measures in this pandemic, this cost may compromise useful microbiota functions. How hygiene measures affect the microbiome is a crucial research question. If loss of microbiome diversity occurs, and potentially even microbial extinction, could these microbial changes ultimately affect rates of asthma, obesity, or diabetes and other diseases that have microbial links? More critically, are there possible measures that might be taken during the pandemic to counterbalance the potential damage to the microbiome and ultimately catalyze other diseases associated with microbiome shifts? Over time, fear of pathogenic microbes can be balanced with a more nuanced attitude recognizing that taxonomically diverse microbiomes are known to strengthen immune systems and provide other benefits.

Note that no balanced, nuanced approach has been taken to attenuate any damage to the microbiome. I’m unaware of any acknowledgement that the microbiome should be a factor in the overall COVID context, and in fact messaging for COVID has continuously emphasized vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and NPIs as the only way of dealing with the virus. Even more concerning, the fear tactics used for COVID has made many people hypochondriacs, causing them to worry about every little bacteria or virus out there.

So not only has the microbiome been ignored, but we may have created a generation of individuals afraid of getting sick from anything, relegating themselves to practices that will leave them horrendously unwell overall.

Interestingly, it may be important to look at our houses and other enclosed environments as having their own microbiomes.

An article from 2014 from Arnold, C.3 raised this question in regards to hospitals where constant cleaning and sterilizing is conducted.

To that effect, some scientists are wondering if constant cleaning may have an ironic consequence for hospitals, in which the bare environments may serve as places for pathogenic bacteria to colonize, almost like how pathogenic bacteria and pathobionts may colonize places within our bodies that would normally contain beneficial bacteria, if not made bare from antibiotics and other hygienic practices.

Arnold, C. notes this in her review:

Hospital-acquired infections aren’t a new phenomenon. As long as sick people have sought care in hospitals, there has been the potential for the spread of infectious disease. With the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics, concerns about disease transmission diminished because physicians believed they had a magic bullet to fight whatever infections a person might acquire.4 The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has changed that thinking.

Today, antibiotic-resistant infections show no signs of stopping, nor do hospital-acquired diseases.3Historically, these infections have been blamed on the presence of harmful bacteria, and increasingly stringent infection-control procedures and standards for sterility have been seen as the solution.5 A new hypothesis says that hospital-acquired infections are being driven not by the existence of harmful microbes but by the absence of helpful species.

Underneath the bright lights and on the stainless steel gurneys lives a large community of microorganisms, most of which are harmless and some potentially beneficial.6 Hospital microbiomes, some researchers think, form a key part of a hospital’s “immune system” and in some cases may help protect patients against infectious diseases.

“For the past 150 years, we’ve been literally trying to just kill bacteria. There is now a multitude of evidence to suggest that this kill-all approach isn’t working,” Gilbert says. “We’re now trying to understand that maybe, just maybe, if we could cultivate nonpathogenic bacteria on hospital surfaces, then we could see if that would lead to a healthier hospital environment.”

It doesn’t appear that this hypothesis has been fully examined, but it raises an interesting point, in that there is a dynamic relationship between us and our environment, and this relationship also relates to the microbes in us and around us.

It’s something we’re aware of, hence the use of disinfectants and bleach. But we tend not to think of the surfaces we clean or the air that we breath being infested with plenty of beneficial microbes-it’s always the harmful ones that we focus on, and it’s this parochial perspective that is possibly harming us.

Poor Diet and Gut Dysbiosis

Although not specifically related to sterility, it’s important to note that 3 years of poor eating are likely to have damaged our microbiome as well.

Lockdowns may have altered food supplies, and many people may have taken to ordering online rather than cooking for themselves. High fat and high sugar foods may influence gut microbiota to selectively increase the number of bacteria that deal with fats and sugar, much to the detriment of the other beneficial microbes. Preservatives are likely to also have antimicrobial effects and reduce the gut flora.

Finlay, et al. notes the following:

At the physiological level, pandemic-induced changes in dietary patterns may influence nutrients available to gut microbiota, possibly tipping the balance from beneficial toward detrimental gut bacterial functions and potentially contributing to intestinal inflammation and a host of chronic diseases (49). To be sure, for specific populations, consumption of healthier, fiber-rich diets may favor a better balance of gut bacteria and greater resistance to the coronavirus (50). Understanding the microbial consequences of these COVID-19−induced dietary shifts and developing interventions, particularly for infants and children, is important. It will be even more critical to do so in vulnerable populations who do not have access to enough or sufficiently nutritious diets during and after the pandemic. Chronic malnutrition and stunting among sub-Saharan African children is associated with gastrointestinal tract bacterial “decompartmentalization,” so that oropharyngeal bacteria are displaced to pathways from the stomach to the colon (51). Such markers are associated with lifelong health problems, from susceptibility to further infection to psychomotor developmental delays. Moreover, a recent Lancet Commission underscored the overlap of malnutrition and obesity, increasingly a problem in LMICs (52). For many populations, then, COVID-19 dietary changes may be exacerbating these already serious conditions associated with microbiome-related dysbiosis.

There’s a bit of a cause/effect issue in regards to the gut microbiome and other diseases, but either way the evidence suggests a correlation between obesity and gut dysbiosis. It may be that poor eating habits leads to changes in gut flora, which then produce signals to continue such poor eating habits that may lead to obesity and other maladies. It’s also possible that obesity and the chronic inflammation may damage the beneficial microbes, and may be a downstream effect of obesity as a whole.

Regardless, given the fact that the lockdowns have increased obesity rates, including in the young4, there are likely to be severe issues of gut dysbiosis that, once again, have not been properly addressed.

I’m reminded of many stories detailing children coming down with serious stomach issues, either last year or earlier this year. Of course, the go-to response is to consider the vaccines. Although the COVID vaccines shouldn’t be taken off the table, it’s likely that other factors are at play as well, including damaged microbiomes that may lead to gut inflammation and other GI issues.

Ramifications of Pharmaceutical Interventions

In regards to pharmaceuticals we tend to think solely of the effects of antibiotics on our microbiome, which may become severely depleted through chronic antibiotic use.

However, we tend to forget that many antivirals are themselves indiscriminate, such that antiviral medications may also act as antibacterial agents as well. This is important given the context of COVID and use of prophylactic agents, which may have consequences on our microbiome in the long run.

For instance, there’s been a growing concern over the use of mouthwash and alterations in oral bacteria, and possible effects on mouth and esophageal cancer, as well as hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

It’s suspected part of this may be due to removal of nitrate/nitrite reducing bacteria5, which may have consequences on cardiovascular disease due to the lack of nitric oxide, a molecule critical for cardiovascular health. Use of mouthwash may also select for certain bacteria that may increase the risk of cancer.

As of now, the data doesn’t appear to be there to draw strong correlations, and concerns over mouthwash use tend to circulate around the use of more harsh chemicals such as chlorhexidine6, which is known to be a strong disinfectant. In contrast, studies using typical mouthwashes have shown mixed results.

So to what extent chronic use of mouthwash has on oral microbiome is unclear, as it appears that this is a new field of interest. However, it does raise concerns of indiscriminate use of various mouthwashes and how this could influence our oral microbiome.

In a similar vein, concerns with mouthwash may extend over to the use of povidone-iodine (PI) nasal sprays and mouth rinses as a prophylactic against SARS-COV2. Use of povidone-iodine in a surgical setting has been done to decolonize bacteria in the nose, in particular Staphylococcus aureus which is one of a growing list of bacteria becoming resistant to antibiotics7.

In the acute phase, the use of PI may be beneficial for surgeries in order to reduce contamination and spread of pathogens. However, longitudinal use may be harmful for the nasal microbiome, as it may remove beneficial nasal bacteria and may contribute to dysbiosis.

There doesn’t appear to be evidence in the literature of long-term use of such interventions on the nasal microbiome. However, research is looking into differences of sinus microbiome and their role in chronic rhinosinusitis8. It's not too much of a stretch to consider the long term ramifications of PI use as prophylactic on the microbiome, although research is needed to validate this concern.

In short, when we consider the fight against SARS-COV2 we may find that various methods used, including possible prophylactic methods, may end up becoming a detriment to our microbiome.

Note that ivermectin is being examined as a possible antibacterial agent with mixed results so far9. Even then, many drugs are constantly being looked at and reexamined for their efficaciousness against other pathogenic agents. It's not a surprise when many of these drugs may have broad spectrum activity, but this broad activity may serve as a detriment to our microbiome if they may be targeted by such therapeutics through chronic and long term use.

In that regard, it’s worth considering the multiple factors that go into the use of pharmaceuticals aside from its effects on the given pathogen, especially if they may alter our microbiome.

The attempts to curb SARS-COV2 have never made any sense. They’ve always been done in a parochial attempt to target one virus at the cost of downstream harms.

Although many people have commented on the effects of lockdowns and masking on obesity and other diseases, the microbiome appears to have been extensively overlooked, and in fact many of these attempts at sterility are likely to be detrimental to our overall health by sterilizing us from critical bacteria that aid in our overall health.

Our microbiome is far more important to our overall health than we give it credit for, and research continues to rebut many of the previously held notions on how to deal with pathogens, as many of these approaches are likely to have ramifications on our microbiome.

Masking, especially outdoors, may reduce exposure to beneficial microbes. Lack of interaction with others means that microbiomes are not being shared, leading to a possible lack in diversity. Poor eating and pharmaceutical interventions may lead to decolonization and dysbiosis of the microbiome, making us more susceptible to a wide array of diseases.

Much more can be explained here (refer to the Finlay, et al. review for more), but remember that many of your actions don’t just affect yourself, but also the little guys that cover your skin, nose, lungs, and gut. All of these microbes help to protect us from illness, and we tend to take them for granted.

Remember that we are not inherently sterile. Most surfaces that we clean will not become sterile. Bacteria and viruses are all around us, so it’s futile to attempt to remove them by any means necessary. We should not achieve sterility at the cost of our beneficial bacteria, and it’s a shame that many of the messages around COVID have not taken this into consideration.

Remember that you’re more than just you, and that has been far too overlooked during COVID.

Note: I will build off of discussions on the microbiome in future posts, including taking a look at viral infection and the alterations in microbiome and now this could lead to secondary bacterial infections. I’ll also take a look at the microbiome and vaccination (if enough information is out there). So be on the lookout for those!

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Finlay, B. B., Amato, K. R., Azad, M., Blaser, M. J., Bosch, T. C. G., Chu, H., Dominguez-Bello, M. G., Ehrlich, S. D., Elinav, E., Geva-Zatorsky, N., Gros, P., Guillemin, K., Keck, F., Korem, T., McFall-Ngai, M. J., Melby, M. K., Nichter, M., Pettersson, S., Poinar, H., Rees, T., … Giles-Vernick, T. (2021). The hygiene hypothesis, the COVID pandemic, and consequences for the human microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(6), e2010217118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010217118

Bohnacker, S., Troisi, F., de Los Reyes Jiménez, M., & Esser-von Bieren, J. (2020). What Can Parasites Tell Us About the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Asthma and Allergic Diseases. Frontiers in immunology, 11, 2106. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02106

Arnold C. (2014). Rethinking sterile: the hospital microbiome. Environmental health perspectives, 122(7), A182–A187. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.122-A182

La Fauci, G., Montalti, M., Di Valerio, Z., Gori, D., Salomoni, M. G., Salussolia, A., Soldà, G., & Guaraldi, F. (2022). Obesity and COVID-19 in Children and Adolescents: Reciprocal Detrimental Influence-Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(13), 7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137603

Bryan, N. S., Tribble, G., & Angelov, N. (2017). Oral Microbiome and Nitric Oxide: the Missing Link in the Management of Blood Pressure. Current hypertension reports, 19(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-017-0725-2

Bescos, R., Ashworth, A., Cutler, C., Brookes, Z. L., Belfield, L., Rodiles, A., Casas-Agustench, P., Farnham, G., Liddle, L., Burleigh, M., White, D., Easton, C., & Hickson, M. (2020). Effects of Chlorhexidine mouthwash on the oral microbiome. Scientific reports, 10(1), 5254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61912-4

Lepelletier, D., Maillard, J. Y., Pozzetto, B., & Simon, A. (2020). Povidone Iodine: Properties, Mechanisms of Action, and Role in Infection Control and Staphylococcus aureus Decolonization. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 64(9), e00682-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00682-20

Cho, D. Y., Hunter, R. C., & Ramakrishnan, V. R. (2020). The Microbiome and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America, 40(2), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2019.12.009

Crump, A. Ivermectin: enigmatic multifaceted ‘wonder’ drug continues to surprise and exceed expectations. J Antibiot 70, 495–505 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2017.11

I feel like this is one of my main talking points in life - we are meant to be covered in bacteria. Many of these things were drilled into my head by my immunology professor in college. He is the reason I eschew all anti-bacterial soaps & hand sanitizer. I also know someone who was a little too OCD with the hand sanitizer and ended up with warts all over their hands.

Again, as a society we are being short-sighted so we don't see the big picture and the harm it is causing. I look forward to more posts on this topic.

I was just talking to my daughter about this yesterday! She's studying cell structure (8th grade) and was grossed out by the paramecium's flagellum. So we started talking about bacteria and I tried to explain the microbiome but the idea that bacteria were all over and inside her was too much :) I did bring up the issue of antibacterial soap and Purell, etc. adversely affecting our microbiomes and how soap and water is much better than using Purell. This generation, esp. after Covid, loves their Purell!