Socrates' Killer- the parsley lookalike Poison Hemlock

A few notes on a widely found, invasive, and highly toxic plant.

Edit 6/20/2023: Below I mentioned that one should look at the leaves of water and poison hemlock to differentiate them from other, edible species. Note that the leaves of water hemlock are actually different compared to poison hemlock, and should not be conflated as I mistakenly did below. In the case of water hemlock, the leaves are much larger, still showing a pinnate arrangement in the leaf structure, but far longer and bigger (image below for a reference1). Also, note that water hemlock does appear to be native to the Americas, in contrast to poison hemlock which were brought over by Europeans, so this remark was removed to refer only to poison hemlock below. Apologies for the assumption made.

Again, look to Weedom’s post for more visuals and descriptions of poison hemlock, as well as additional information.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the unassuming, highly toxic plant Lily-of-the-valley:

May's heart-stopping flower: Lily of the Valley

Modern Discontent is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. I’ll strangely admit that within the past few years I’ve gro…

This plant contains a seriously toxic cardiac glycoside, wrapped into a very tiny, innocuous-looking plant (although the leaves are rather large in contrast to the flower bulbs).

Nature has a strange way of providing us visual bounties that, by all accounts, can prove rather deadly. This is influenced, in part, by the fact that many toxic plants may look similar to plants that we readily consume.

In the case of lily-of-the-valley, I noted that there was an older couple who accidentally consumed the plants because the husband mistake the leaves for kale.

Such mix-ups can occur quite often, and can lead to accidental death in those who unfortunately confuse edible plants with highly toxic simulacrums.

An example of this is poison hemlock.

Poison hemlock is a plant I’ve seen several times2, and you’ve likely come across it without realizing how toxic this plant is.

Part of my inspiration in looking into poison hemlock was partially derived from how familiar this plant looks. Another part was inspired by Weedom’s post on this plant. Weedom provides a very interesting and detailed description of this plant (with some of the information here being derived from Weedom’s post, as well as other sources).

I encourage people to read from Weedom about this weed that kills (does weed killer still work here?).

Weeds that Kill

In contrast to the tiny stature of lily-of-the-valley, poison hemlock can grow to be rather large, with many white, smelly flowers sprouting from the central stalk.

The stalk of poison hemlock is actually comparable to the dill that has overtaken my backyard, and so in that regard I can see the resemblance and why they are from the same family.

But poison hemlock doesn’t start off life with such massive growth. As Weedom and other accounts have noted, the first year of poison hemlock starts off rather unassuming, looking more like a typical weed rosette more than the massive stalks of poison as shown above:

Poison hemlock is a biennial (2-year) plant, with the first year spent predominately as an unassuming rosette. It’s only within the second year that poison hemlock shoots up in height and produces many flowers and seeds.

Funnily enough, poison hemlock was taken from Europe to the Americas as a garden plant due to the prettiness of the flowers. Unfortunately, this has made these plants invasive, and unfortunately adds to the confusion over edible plants that look rather similar.

In short, poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) belongs to the parsley family Apiaceae along with fennel, dill, and carrots. This classification is not too surprising, given that the leaves of poison hemlock look highly reminiscent to parsley leaves. Poison hemlock also goes by the name "poison parsley” due to these similarities.

Poison hemlock also looks a bit similar to another genus of plants within the parsley family called Cicuta, or water hemlocks. In contrast to poison hemlock, which can be found spread across fields, along highways, or nearby fences, water hemlock is generally found in wet, marshy areas. However, water hemlocks share a similar feature of poison hemlocks in being highly toxic, although the toxin found in water hemlocks is of a different class.

Socrates’ poison- Piperidine Alkaloids

The widespread growth and invasion of poison hemlock has led to several accidental poisonings throughout the years, with many animals who consume hemlock becoming poisoned, and on many occasions dying. In humans, the tubular root of poison hemlock can be mistaken for carrots or wild parsnips, and the leaves may be mistaken by adults, and more often by children, as being similar to parsley, with ingestion of these parts of the plants leading to poisoning and some cases of death.

This is mostly related to the fact that nearly all parts of the plant is toxic, with levels of toxicity varying throughout the season, and even throughout the day.

The literature is filled with case reports of accidental hemlock poisoning, including a case in which a group of young adults on holiday in Argyll sourced what they thought were parsnips from a small stream and used the roots for a curry3. Everyone became poisoned, with two individuals appearing to have suffered grand mal seizures due to the consumption of the suspected parsnips. However, it was later found that the plants were from water hemlock dropwort, and was considered the source of the various symptoms.

There are several other accounts of poisonings, including a 6-year old who mistook poison hemlock in her backyard for parsley,4 as well as a case in 1845 of two boys who brought what they thought was parsley home, which their dad ate copious amounts of, only to later die.5 There’s also a case in which an apparent suicide attempt was made through intravenous injection with hemlock.6

The last case report is a rather interesting one to consider, as hemlock has been used extensively in years past as a method of intentionally poisoning someone, with evidence tracing back hundreds of years for this use of hemlock.

It’s even been argued that Socrates was executed by way of hemlock poisoning, as remarks made about his symptoms during his execution were similar to that of hemlock, including the paralysis which appeared to have spread from his feet to his torso (respiratory failure was the likely cause of death), as well as the loss of balance. However, Plato’s accounts of Socrates’ death appear to have left out a few details, including signs of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, likely due to providing a more heroic portrayal of his death.7

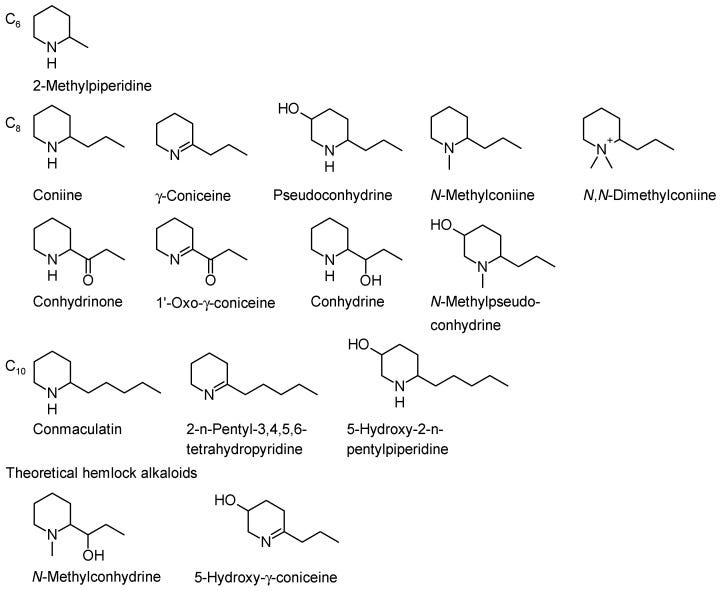

Several compounds have been isolated from poison hemlock, all of which are categorized as piperidine alkaloids.

The word alkaloids refer to organic compounds that generally contain a nitrogen. Piperidine, on the other hand, refers specifically to the compound piperidine which is a 6-member ring with an internalized nitrogen atom:

All piperidine alkaloids, by their very name, contain a piperidine moiety as part of their overall structure.

Several of these piperidine alkaloids can be found below (Hotti, H., & Rischer, H.8):

The most important ones found in poison hemlock are Coniine and N-methylconiine, as well as a few others. Note that water hemlocks contain a different compound called Cicutoxin9, which are far structurally different than piperidine alkaloids.

Piperidine alkaloids operate by way of binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are receptors responsible for muscle contraction as well as actions within the central nervous system. The binding of piperidine alkaloids to these receptors is rather strange, as it appears that the alkaloids first stimulate these receptors (act as an agonist), then completely block their signaling (antagonist) by way of preventing acetylcholine from binding. Thus, neuronal signaling is completely halted, and paralysis sets in.

It should be noted that the structural overlap between piperidine alkaloids and nicotine likely explains this seemingly non-selective binding to these receptors.

Similar to lily-of-the-valley, one may question why such highly toxic compounds would be produced by poison hemlocks.

Hotti, H., & Rischer, H. provide an idea that the alkaloids may attract pollinators. Note that the odor given off by poison hemlocks are rather pungent, and may lie in the nitrogen-rich composition of these alkaloids. So what may appear as unpleasant to us may be attractive to insects.

Interestingly, pitcher plants appear to produce coniine as well. In this case, it’s argued that pitcher plants may attract insects by way of releasing these volatile alkaloids in order to attract unsuspecting insects to their deaths. This appears to explain why these plants, which usually grow in nitrogen-poor climates, may waste their nitrogen to make such compounds- they get back more by way of digesting insects than they lose by the production of these alkaloids.

The alkaloids may also provide a protection to the seeds, as high levels of coniine are found in the outer layer of the seeds and are shed during germination. Such a protective coating may induce sudden vomiting in animals, allowing the seeds to survive. Thus, it may deter vegetation, and could also kill smaller herbivores and insects.

Things to look out for

Although poison hemlock poisoning is not too common, their accidental consumption has proven to be rather deadly.

Therefore, it may be worth recognizing these weeds, as well as signs of toxicity.

The Cleveland Clinic notes some symptoms of poisoning:

Poison hemlock can also be recognized by the leaf structure. The leaves should look darker, and more sharp relative to parsley or the commonly-confused Queen Anne’s lace.

Also, remember that the volatile alkaloid content of these plants make them smell off-putting, and should be used as an evolutionary indication that these plants should be avoided.10

As to touching the plants, the evidence here seems to be a bit mixed. One clear plant to avoid touching is the water hemlock, as the cicutoxin appears to be readily absorbed by the skin. With that being said, several recommendations have taken to suggesting protective wear in order to deal with hemlock, especially for those with sensitive skin.

*Note: For more images and explanations on the structures to pay attention to, please refer to Weedom’s post.

There’s a lot that can be confused out in the wild, so take care to remember that things are safe by way of them being natural. This is likely a hard lesson our species had to learn through trial, error, and plenty of deaths.

Becoming aware of what’s out there, as well as what to avoid, is something worth thinking about in these modern times.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Again, note that the leaves for water hemlock are very distinct, and far different than poison hemlock leaves. Also, as Evil Harry mentioned in the comments, the rosettes formed by young water hemlock also appear more like cilantro/coriander, rather than the finer blades that poison hemlock rosettes make.

I do concede that it may have been cow parsley that I noticed, which looks similar to poison hemlock albeit a bit more delicate in structure:

Downs, C., Phillips, J., Ranger, A., & Farrell, L. (2002). A hemlock water dropwort curry: a case of multiple poisoning. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ, 19(5), 472–473. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.19.5.472

Konca, C., Kahramaner, Z., Bosnak, M., & Kocamaz, H. (2016). Hemlock (Conium Maculatum) Poisoning In A Child. Turkish journal of emergency medicine, 14(1), 34–36. https://doi.org/10.5505/1304.7361.2013.23500

Case of Poisoning with Hemlock. (1845). Provincial medical & surgical journal, 9(27), 426–427.

Brtalik, D., Stopyra, J., & Hannum, J. (2017). Intravenous Poison Hemlock Injection Resulting in Prolonged Respiratory Failure and Encephalopathy. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology, 13(2), 180–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-017-0601-0

Dayan A. D. (2009). What killed Socrates? Toxicological considerations and questions. Postgraduate medical journal, 85(999), 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2008.074922

Hotti, H., & Rischer, H. (2017). The killer of Socrates: Coniine and Related Alkaloids in the Plant Kingdom. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 22(11), 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111962

In the case of the people on holiday, it appeared that some of the people in the party were hesitant to eat the plant due to the uncertainty in its sourcing, as well as its apparent bitterness.

Very cool post! I do, actually use Lily of the Valley in minute amounts, but not Poison Hemlock... although, it can also be used in minute amounts for extreme conditions of high blood pressure and rapid heart rate. Neither should ever be used by someone who has not had a lifetime of training in herbal medicine at a very high level.

My mom picked some wild fennel on a hike with me when I was young. Unfortunately, that encouraged me to eat quite a few fennel-looking wild plants in my youth. In retrospect, I'm lucky to have not picked any hemlock or other nasties.

If you decide to teach your kids wild edible plants be sure to very carefully, and repeatedly, stress proper identification and hazards - don't even mention it as a one-off!