Remdesivir Retrospective: Problems with the NEJM Ebola clinical trial

Rebutting the narrative that 50% of the people within the Remdesivir arm of the Ebola study died FROM Remdesivir.

Given some of the current issues in analyzing studies I thought it necessary to do a relook at one clinical trial related to Remdesivir.

Remdesivir is a highly controversial drug as it was one of the only antivirals approved for use against COVID during the early months. It was also an agent that had to be used inpatient and usually on patients that were likely already dealing with complications related to SARS-COV2.

Of course, this scenario would raise serious criticisms of the use of this drug.

However, over time a narrative began to craft around the dangers of Remdesivir, mostly based on a clinical trial published in NEJM1 at the end of 2019 in which Remdesivir was one of the agents used against Ebola.

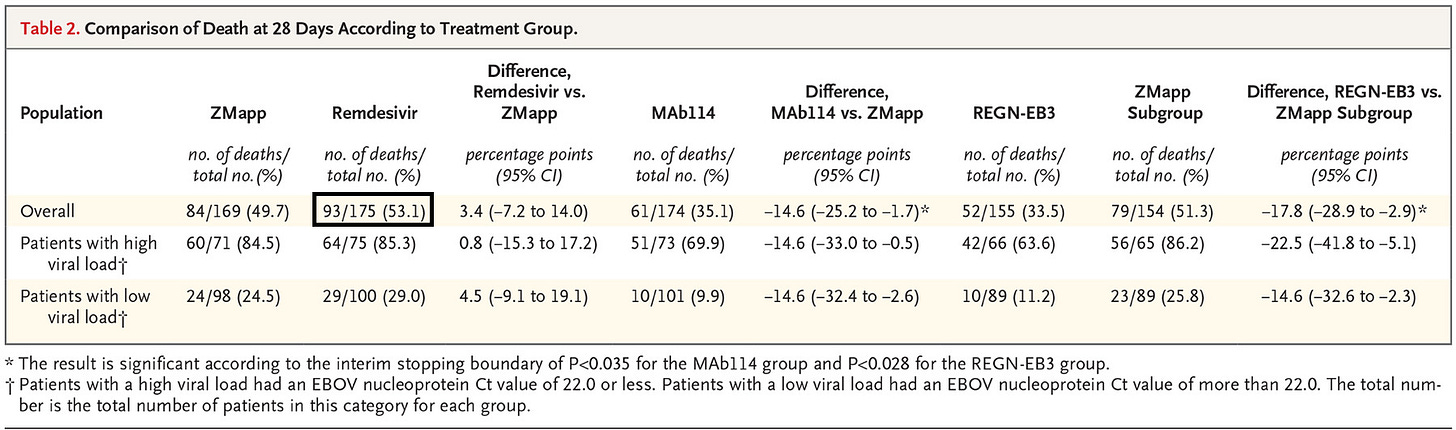

One narrative in particular was to suggest that 50% of the people within the Remdesivir group died from Remdesivir, which is likely based on this table in particular:

There are many concerns with respect to Remdesivir, but at the time when I originally covered this trial I didn’t look too closely into clinical trials and many of the problems that may come with them.

But we’ve also been through a time in which Ivermectin studies were heavily scrutinized for serious issues with respect to randomization, sampling, timing of treatment, and dosage as covered in detail by Alexandros Marinos in his Substack Do Your Own Research:

In lieu of the Ivermectin clinical trial audits one would assume that more careful scrutiny of studies would be encouraged.

But this also wasn’t the case when studies with respect to Ivermectin would make their way onto either Twitter or Substack.

If a study suggested that Ivermectin didn’t work then you could bet that the pro-IVM group would look at the study with a fine-toothed comb while the anti-IVM will trust whatever is stated in a study’s abstract.

If a study showed that IVM may be effective then the tables are turned- you can guarantee that the pro-IVM group will just take the results at face value while the anti-IVM group does the heavy scrutinizing.

I found this dynamic so strange- why isn’t it that both groups scrutinize studies irrespective of whether the results align with our own biases? And in fact, shouldn’t people be more inclined to make sure that a study that aligns with their own biases becomes heavily scrutinized so that it strengthens the actual arguments if said studies were not heavily flawed?

Unfortunately, this doesn’t appear to be the case. Rather, it appears that people are more inclined to rush to post abstracts and extrapolate from there rather than engage with a study.

It’s why I have criticized “no myocarditis” remarks based on a misreading of a systematic review, or why anti-spike egg narratives overlooked the fact that you need to vaccinate chickens in order to produce anti-spike antibodies- you know, that little thing called the adaptive immune system that everyone should at least be aware of by now and prevent one from making immediate assumptions about eggs and antibodies?

Note that the intent of this post is not to question the effectiveness of Remdesivir- there are several problems with the drug and I’ll provide my own perspective on the matter at the end of this post. Rather, the intent here is to point out why this notion that Remdesivir killed 50% of the people within the trial is absolutely incorrect, and should not be coming from people who know better than to make such claims.

Study Design Issues

Rather than hash out every bit of this study we can use the criticisms raised against IVM clinical trials as a frame of reference.

Again, remember that the main criticisms against IVM trials fall into some of the categories below:

Low dosage

Delayed treatment

Improper randomization

There are likely a few more but I’ll focus on these categories.

1. Low dosage in both Remdesivir and ZMapp groups

Claims have been made that IVM clinical trials tended to use too low of a dose to treat patients.

In order to provide a consistent argument we should then look and see if low dosage was an issue across many clinical trials including this Ebola trial.

Between the 4 groups both the ZMapp and Remdesivir treatment groups were given the designated treatment over the course of nearly 10 days while those within the monoclonal antibody groups (MAb114 and REGN-EB3) were administered one full dose at the time of administration:

All four trial agents were administered intravenously. Patients in the ZMapp group received a dose of 50 mg per kilogram of body weight every third day beginning on day 1 (for a total of three doses). Patients in the remdesivir group received a loading dose on day 1 (200 mg in adults, and adjusted for body weight in pediatric patients), followed by a daily maintenance dose (100 mg in adults) starting on day 2 and continuing for 9 to 13 days, depending on viral load. Patients in the MAb114 group received a dose of 50 mg per kilogram, administered as a single infusion on day 1. Patients in the REGN-EB3 group received a dose of 150 mg per kilogram, administered as a single infusion on day 1.

A loading dose followed by a maintenance dose has been argued as a method of administering IVM so this isn’t too out of the ordinary. However, it’s important to also remember that Ebola is a much more deadly disease, and so it may be necessary to administer a higher dose early on to reach a high enough serum level.

Here, the researchers posit whether the low dosages that took days to increase may have played a factor in the difference in outcomes between the 4 groups:

Given that 97% of deaths in this trial occurred within 10 days after enrollment, the efficacy of MAb114 and REGN-EB3 as compared with that of ZMapp and remdesivir might be partly attributable to the fact that the full treatment courses of MAb114 and REGN-EB3 were administered in a single dose, whereas ZMapp and remdesivir were administered in multiple infusions. Differences in the time to appearance of the first negative nucleoprotein Ct result among trial groups support this observation; patients in the MAb114 and REGN-EB3 groups had faster rates of viral clearance than patients in the ZMapp and remdesivir groups. With ZMapp, the longer preparation time and the recommendation to allot up to 4 hours for the infusion of the first dose led to some delays in initiating therapy until the following day for patients who arrived later in the day to their respective treatment centers. However, in a sensitivity analysis, mortality was only slightly lower when ZMapp recipients with delayed therapy were excluded.

Again, note here that nearly 97% of the deaths occurred within 10 days after enrollment. That would suggest that a large portion of those within the ZMapp and Remdesivir arms of the trials likely did not even receive all of their doses before passing relative to those within the monoclonal antibody arms of the study.

It’s hard to argue what the proper dosages should have been for the ZMapp and Remdesivir groups, however the fact that dosages were inconsistent among all 4 arms would raise questions as to whether this had a huge impact on the mortality rates.

2. Delayed Treatment

But speaking of timing we should all be aware that early treatment would likely be the best approach in dealing with an infection.

With many COVID treatments even a delay of 5 days may be considered far too much when trying to treat the disease.

Unfortunately, the Ebola treatments appear to have been delayed by an average of around 5 days:

Patients were enrolled within an average of 5.5 days after the onset of symptoms. The most commonly reported baseline symptoms were diarrhea (in 53.8% of the patients), fever (in 51.4%), abdominal pain (in 46.4%), headache (in 44.4%), and vomiting (in 39.4%) (Table S2). Malaria coinfection was identified in 57 of 557 patients (10.2%).

So many of these individuals were likely already dealing with a more progressive course of the disease at the point that they were randomized and given treatments. Several patients died prior to even being given any treatment:

Twelve patients were enrolled but died before receiving the first infusion: one in the ZMapp group, three in the remdesivir group, three in the MAb114 group, and five in the REGN-EB3 group.

It’s important to remember, and apparently something that many people have forgotten, but Ebola has an extremely high case fatality rate, much greater than SARS-COV2.

In fact, so high is the case fatality rate that the researchers here posited that a delay of treatment increased the odds of dying per day that patients did not receive treatment (emphasis mine):

A longer duration of symptoms before treatment was associated with significantly worse outcomes. Of note, 19% of patients who arrived at the treatment center within 1 day after the reported onset of symptoms died, as compared with 47% of patients who arrived after they had had symptoms for 5 days (Table S4). The odds of death increased by 11% (95% CI, 5 to 16) for each day after the onset of symptoms that the patient did not present to the treatment center (Table 3).

I don’t want to look exactly at this 11% value, but let’s suppose that the risk of death increases with each day that treatment is not provided. Given that patients were not enrolled until 5.5 days after symptom onset (on average) wouldn’t this inherently suggest that the mortality rates would be biased high on all accounts?

Paired with slow dosage in both the ZMapp and Remdesivir groups it’s not hard to see why the mortality rates were so high in these groups.

The researchers even comment on the need for early treatment:

In addition to differential effects of the four trial agents with respect to mortality, the results showed the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. We observed an 11% increase in the odds of death for each day that symptoms persisted before enrollment. These data highlight the need for community awareness that earlier diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased survival.

Paired with dosage issues it’s quite clear that the study design may have been doomed to fail. It doesn’t mean that ZMapp or Remdesivir would be effective against Ebola (to provide context ZMapp was considered the go-to treatment option for years), but that such a study design will inherently lead to a high mortality rate irrespective of what treatment was provided. However, given the lower dosage and the progression of the disease it’s hard to argue that both the ZMapp and Remdesivir groups would likely be affected.

3. Inconsistent randomization

Generally one would expect that the makeup of each arm of a study would be similar, including in various biomarkers and disease progression.

Here, it appears that several biomarkers related to organ dysfunction and damage were relatively higher in the ZMapp and Remdesivir arms:

The mean baseline serum creatinine level was 2.5±2.9 mg per deciliter (221±256 μmol per liter), the mean aspartate aminotransferase level was 668±700 U per liter, and the mean alanine aminotransferase level was 379±464 U per liter. The mean baseline creatinine and aspartate aminotransferase values were higher in the ZMapp and remdesivir groups than in the other two groups.

Elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase may be indicative of liver damage, although this enzyme is found in other organs as well. Creatinine may be a biomarker of kidney damage. Therefore, elevated levels may suggest that those within the ZMapp and Remdesivir groups may be more sick and may be a contributory factor in the outcomes of those within these treatment arms:

Although most characteristics at baseline were balanced across the four groups, values for serum creatinine and aminotransferases were higher in the ZMapp and remdesivir groups than in the MAb114 and REGN-EB3 groups; patients in the latter groups had better outcomes, despite similar durations of illness before enrollment. This suggests that enrolled patients might, on average, have been somewhat sicker in the ZMapp and the remdesivir groups, which could potentially account for some of the differences in outcomes.

It’s important to note that several participants were missing baseline data so the differences in values may be related to the lack of information for some participants. Additional statistical analyses appear to suggest that these differences didn’t lead to huge differences in outcomes.

But when taken altogether it’s quite clear that more is going on than just “50% of those given Remdesivir died”. SARS-COV2 has nowhere near the same case fatality rate as Ebola, and given all of these issues with the study’s design it’s hard to argue that such a narrative can be even crafted.

If this study was used to argue that IVM led to the death of 50% of those who were prescribed the drug obvious red flags would have been raised criticizing the study, and yet no one seems to have looked at this study and raised questions about some of its findings.

The idea that 50% of those given Remdesivir died is already a ludicrous statement, especially when used by those who argue the nuances of dying with COVID vs dying from COVID. How is it that these same people don’t appear to apply that same level of nuance when it comes to Remdesivir?

My point is not to argue that Remdesivir is safe, but to raise the point that there appears to be a lack of consistency in how we examine studies. If it proves our point we are more inclined to overlook design flaws and issues in how data is being presented. If it goes against our narrative we will be more inclined to dissect a study as Alexandros Marinos has done with several IVM studies.

So does this mean that Remdesivr is safe? I’m not going to argue that point, but as it relates to the use of Remdesivir for COVID I have generally leaned towards the same standards as Hydroxychloroquine.

That is, it’s apparent that late-use of Hydroxychloroquine, likely at a time when organ damage may be perfuse in hospitalized patients, may cause more harm than good. It’s likely here where risk factors for adverse reactions with respect to HCQ may be higher relative to early use of the drug.

I would argue that the risk of nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity related to Remdesivir may be due to the late use of the drug in the same way that HCQ appears to cause more harm when prescribed late.

This is a reminder that it is not just about whether a drug acts as a good antiviral agent, but that the timing of a drug relative to other risk factors should be taken into account.

Remdesivir has many problems, but to argue that it killed 50% of the people within the Ebola trial makes no sense.

Also, I’m failing this “shorter posts” endeavor… Well, there’s always next time!

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Mulangu, S., Dodd, L. E., Davey, R. T., Jr, Tshiani Mbaya, O., Proschan, M., Mukadi, D., Lusakibanza Manzo, M., Nzolo, D., Tshomba Oloma, A., Ibanda, A., Ali, R., Coulibaly, S., Levine, A. C., Grais, R., Diaz, J., Lane, H. C., Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J., PALM Writing Group, Sivahera, B., Camara, M., … PALM Consortium Study Team (2019). A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Ebola Virus Disease Therapeutics. The New England journal of medicine, 381(24), 2293–2303. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910993

Ebola kills on average 50%, so looks like Remdesivir was ineffective. There was no placebo control group due to ethical reasons.

This was likely a much younger population than with COVID patients and no doubt they had better kidney function than many elderly COVID patients, plus I expect the doses/duration was not the same, so I still think there may have been harm done with its use with COVID , but we just don't have any good data to show this, just many anecdotal reports

This may really sound stupid...

...but I think most people would understand

You stop going out and initiate early prophylactic care IMMEDIATELY upon early symptoms; even mild congestion, sore throat, cough...

...many of these diseases spread significantly faster by symptomatic carriers

American Health Initiatives; exercise, diet, fresh air and sunshine, vitamins, minerals and naturopathic prophylaxis quercetin, nattokinase prior to the more “off labor”; nasal flushes, gargles, NSAIDS then Ivermection, Prednisone, with more easily prescribed Doxy, Zinthro, Keflex...

...maybe the days of worrying about superinfections from widespread basic antibiotic use is over

I just stocked up, including some Cipro for Anthrax and Potassium Iodide for biden’s*WWIII...