Rebuking the Moderna Patent Paper

A case of scientific "listen and believe".

On Sunday Igor Chudov posted a very succinct paper on SARS-COV2 and it’s possible history of engineering, including information on the gp120 protein’s1 role in pathogenicity and possible targeting of CD4+ T cells.

Now, I will say I tend to disagree with Igor, mostly because I am a bit OCD in trying to piece things together- if it doesn’t fit I can’t commit (sorry, watching too much of the Depp/Heard trial!)

I need to get to the root of the information in order to figure out what is happening- it’s why I prefer looking at pharmacology studies and mechanisms of actions rather than clinical trials since it at least tells me what is binding to what else.

All this to say that this article actually tied up many pieces that I had trouble assessing the veracity of. It’s a good article that contains a few things we’ve seen before but it’s still worth reading.

However, one thing that I still could not figure out was the Moderna Patent issue. The Moderna Patent issue refers to a 19-nucleotide sequence found in both SARS-COV2’s spike protein as well as in one of Moderna’s patented sequences. It comes from this paper in frontiers in Virology and circulated around all corners of the internet, including appearing in mainstream media outlets such as The Daily Mail.

As of this writing the article has received nearly 380,000 views, nearly unheard of for a paper!

But I had a lot of issues when first hearing of this paper.

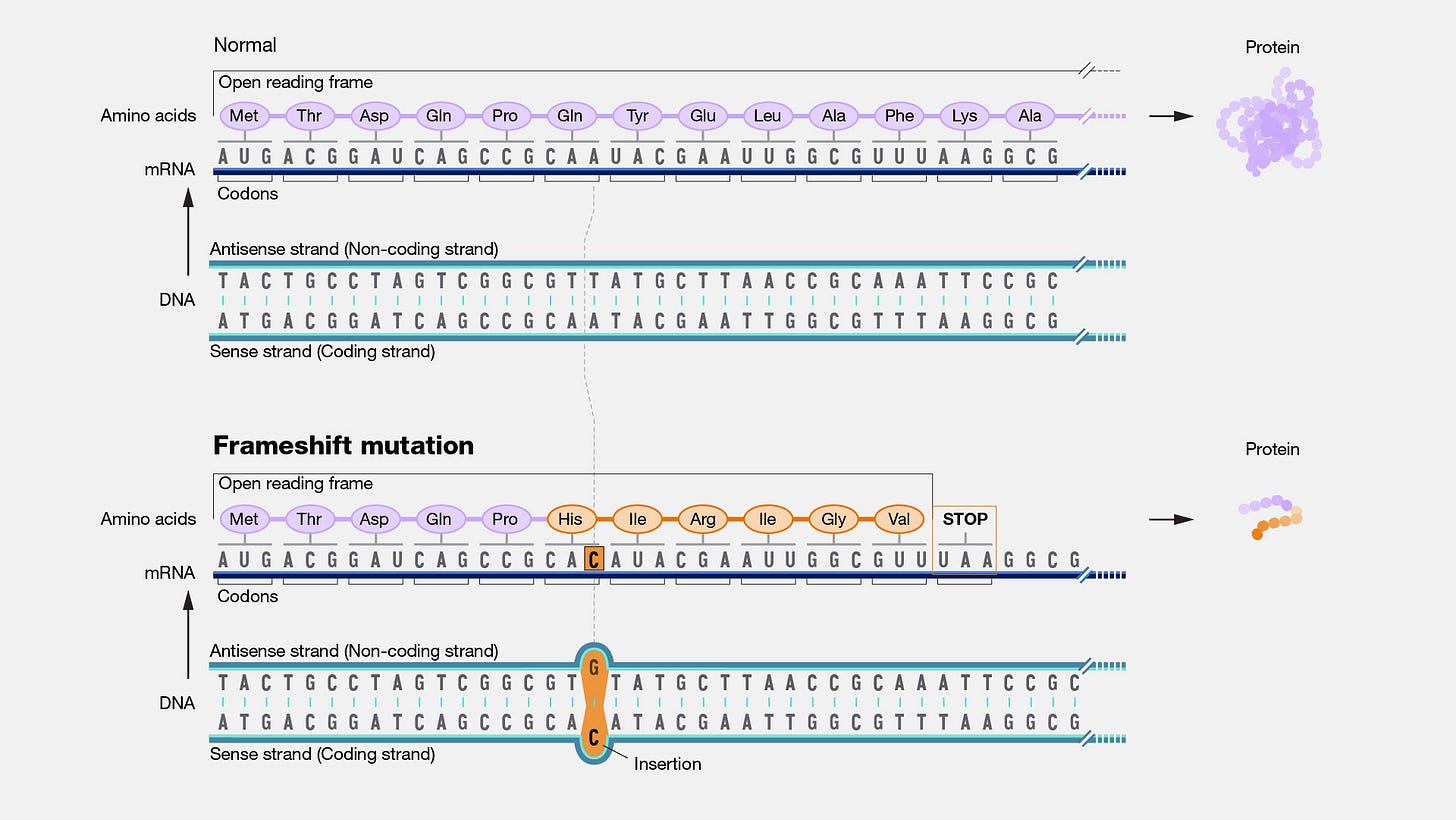

A 19-nucleotide sequence breaks the rule of 3 for nucleotides (AKA The Triple Code)- if the sequence is not divisible by 3 then it’s going to wreak havoc on the proceeding protein because it’s going to alter downstream codons and the produced amino acids.

Usually this lack of divisibility occurs in frameshift mutations where a nucleotide is either inserted or deleted from a genome. It’s called a frameshift mutation because it shifts all downstream codons and causes them to code for different amino acids because of the subsequent . The only saving grace is if the insertion or deletion is a multiple of 3 itself, leading only to the addition or removal of one amino acid.

So this creates a strange paradox- how is it that this 19-nucleotide insertion occurs cleanly? The only possible reason would be if multiple codons were removed plus 1 to make room for the addition of the 1 extra nucleotide from the 19 nucleotide sequence seen in the MSH3 protein. Again, how cleanly could these two actions be?

In order to figure this out it may require that we examine the process conducted by the researchers and flush out their thought process.

For that, I’ll cut out this part of the study that’s worth examining:

A peculiar feature of the nucleotide sequence encoding the PRRA furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 S protein is its two consecutive CGG codons. This arginine codon is rare in coronaviruses: relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of CGG in pangolin CoV is 0, in bat CoV 0.08, in SARS-CoV 0.19, in MERS-CoV 0.25, and in SARS-CoV-2 0.299 (9).

This part is absolutely true. The PRRA amino acid sequence is certainly an insertion- it’s not seen in any other coronavirus, and it’s not misplacing any other would-be amino acids (as far as I’m aware). Even more importantly is the strange codons for the arginine insertions. This is something that people have mentioned before, but for those unaware certain codons appear with greater frequencies in certain species because certain nucleotides are more predominate across various species.

The CGG codon that codes for arginine is not something seen in other viruses- it’s actually a codon typically seen in eukaryotes/humans. It’s one of the reasons that this sequence seems very fishy-how could a codon typically seen in humans end up in a virus?

This was pictured in one of the articles provided2 by Igor that raised question about the FCS.

One possibility is that it was inserted through serial passage through cell lines. Another possibility could be that the sequence was artificially inserted intentionally. Either way, the sequence somehow ended up there and aids in the virus’ transmissibility and pathogenicity.

A BLAST search for the 12-nucleotide insertion led us to a 100% reverse match in a proprietary sequence (SEQ ID11652, nt 2751-2733) found in the US patent 9,587,003 filed on Feb. 4, 2016 (10) (Figure 1). Examination of SEQ ID11652 revealed that the match extends beyond the 12-nucleotide insertion to a 19-nucleotide sequence: 5′-CTACGTGCCCGCCGAGGAG-3′ (nt 2733-2751 of SEQ ID11652), such that the resulting mRNA would have 3′- GAUGCACGGGCGGCUCCUC-5′, or equivalently 5′- CU CCU CGG CGG GCA CGU AG-3′ (nucleotides 23547-23565 in the SARS-CoV-2 genome, in which the four bold codons yield PRRA, amino acids 681–684 of its spike protein). This is very rare in the NCBI BLAST database.

I have a lot of trouble with this section. Why start with the premise that you should check through the patent rather than other sequences first? Even if we argue that this sequence is of human origin why not start searching through other genomes first?

When using BLAST you choose which database to search through, including one that specifically searchers for that sequence within a patent3, which is not something I would have started with first.

Interestingly I can’t find anything when I enter just the 12-nucleotide sequence; mostly because that sequence is far too short and would provide far too many results, thus the search does not come back with any results and only provides an error.

But try it by limiting it to “homo sapiens” and we can clearly see this sequence is found in many of our proteins. That would at least indicate that this sequence is not necessarily special.

I’m also having the same difficulty when trying to search through the patent database- the 12 nucleotide sequence is far too short.

Maybe it’s because I’m not as well trained in the ways of the BLAST, but this makes me wonder how easily the researchers were able to come across this sequence in this Moderna patent, as it appears that a longer sequence is needed to come back with a result.

If I’m having this much difficult when intentionally trying to find the sequence (without using the given 19-nucleotide sequence), how likely was it that the researchers came across it serendipitously?

I thought it was rather strange that the researchers never expanded or clarified as to how they conducted their search- did they happened to have plugged it into BLAST and got the sequence right there? Or, and this is my speculation, did they know what to look for beforehand and outlined the plausible process to get there? I think it’s rather interesting no one brought up the question as to how they came across this sequence, but just accepted that they happened to stumble across it.

The proprietary sequence SEQ ID11652, read in the forward direction, encodes a 100% amino acid match to the human mut S homolog 3 (MSH3) (9). MSH3 is a DNA mismatch repair protein (part of the MutS beta complex) (11). SEQ ID11652 is transcribed to a MSH3 mRNA that appears to be codon optimized for humans (12). We did not find the 19-nucleotide sequence CTCCTCGGCGGGCACGTAG in any eukaryotic or viral genomes except SARS-CoV-2 with 100% coverage and identity in the BLAST database (Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Now this actually led me to something I completely overlooked. I first considered that the 19-nucleotide sequence was the entirety of the patent and based my judgement on that. But upon further viewing, as well as looking back at some of Igor’s posts, it’s not just the 19-nucleotides alone, but actually part of a part of a bigger whole. The Sequence of 11652 is part of Patent US 9587003 and this sequence alone is nearly 3k bases in length.

The more important issue is how this specific sequence out of the entire 3,000 nucleotide sequence happened to be “the one”, and it was the only one that was placed so neatly into the proper spike sequence? What about the other sequences, or over 3,000 nucleotides?

And that leads me to my conclusion.

Keep It Simple, Stupid!

The researchers mentioned that this sequence being related to the Moderna patent and this MSH3 protein indicates something may have happened to lead part of this patent to be inserted.

Other people, including ones on Substack indicated that this may have occurred through serial passage leading to an eventual insertion via passage through cell lines that express MSH3, possibly in a Moderna lab. But if I haven’t made it clear before I’ll make it clear here- this process is far too complicated.

Somehow we are to believe that this sequence happened to have inserted itself at the perfect site, was comprised of a 19-nucleotide sequence meaning that at least one nucleotide was deleted but that newly inserted nucleotide still coded for the same protein (take a look at the FCS amino acid sequence above- the only difference is the PRRA insertion)?

Or, could it be possible that the 12 nucleotide sequence was intentionally added sans any serial passage?

The premise that this sequence was inserted through serial passage only works if serial passage was conducted with the intent of adding this sequence, and cleanly at that. Again, how likely would this have occurred?

The issue with this flow of logic is that it attempts to find evidence that fits the conclusions. for me, the conclusions is what’s problematic because it seems far too complicated of an approach.

We can see this as well with the PNAS article which provides a different explanation as to where the sequences came from:

In fact, the assertion that the FCS in SARS-CoV-2 has an unusual, nonstandard amino acid sequence is false. The amino acid sequence of the FCS in SARS-CoV-2 also exists in the human ENaC α subunit (16), where it is known to be functional and has been extensively studied (17, 18). The FCS of human ENaC α has the amino acid sequence RRAR'SVAS (Fig. 2), an eight–amino-acid sequence that is perfectly identical with the FCS of SARS-CoV-2 (16). ENaC is an epithelial sodium channel, expressed on the apical surface of epithelial cells in the kidney, colon, and airways (19, 20), that plays a critical role in controlling fluid exchange. The ENaC α subunit has a functional FCS (17, 18) that is essential for ion channel function (19) and has been characterized in a variety of species. The FCS sequence of human ENaC α (20) is identical in chimpanzee, bonobo, orangutan, and gorilla (SI Appendix, Fig. 1), but diverges in all other species, even primates, except one. (The one non-human non-great ape species with the same sequence is Pipistrellus kuhlii, a bat species found in Europe and Western Asia; other bat species, including Rhinolophus ferrumequinem, have a different FCS sequence in ENaC α [RKAR'SAAS]).[…]

We do not know whether the insertion of the FCS was the result of natural evolution (2, 13)—perhaps via a recombination event in an intermediate mammal or a human (13, 24)—or was the result of a deliberate introduction of the FCS into a SARS-like virus as part of a laboratory experiment. We do know that the insertion of such FCS sequences into SARS-like viruses was a specific goal of work proposed by the EHA-WIV-UNC partnership within a 2018 grant proposal (“DEFUSE”) that was submitted to the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (25). The 2018 proposal to DARPA was not funded, but we do not know whether some of the proposed work was subsequently carried out in 2018 or 2019, perhaps using another source of funding.

But this explanation also precludes the additional proline residue (P), and so this review is also insufficient in explaining the origins of the PRRA sequence in its entirety.

Both explanations are not sufficient, although they raise concerns to unnatural origins.

But as it pertains to this 19-nucleotide sequence and the Ambati, et. al. study, I don’t find their conclusions plausible for the mere fact that their results appear to fit a conclusion that they may (big MAY) have already had- they may have know what to look for.

By doing so they [the researchers] went far beyond the scope of the analysis, possibly including erroneous nucleotides that did not need to be originally included in their assessment.

Of course, this led other people to go down that rabbit hole and search for the ties between Moderna and this insertion BECAUSE they are starting from the position that this is the direction they should head down. This could have been purely coincidental, but this insertion claim itself could complicate the assessment of this sequence- of course we wouldn’t see this sequence in many other places if it was intentionally inserted, and examinations of these sequences have to take that into consideration.

Remember the phrase: Keep it Simple, Stupid! Beware of complicating the matters more than is necessary. As it stands, it’s far easier to consider a 12-nucleotide clean insertion rather than one that requires quite a good deal of extra work to get to the results needed.

Either way, I don’t think these researchers just happened to come across this similarity in sequence. I also don’t contribute any nefarious doings of the researchers, but part of me wonders if they happened to have found this similarity and worked backwards to explain how they came across it in a more artificial manner.

But I’d like to hear other explanations and criticisms, or any clarifications if this post was far too confusing.

I also will add that upon further examination there were questions raised because of the small sequence used by the researchers, and it appears that this is the reason for the redaction. I can’t speak to the veracity of this assessment as I have not actually looked at the spike sequence.

Harrison, N. L., & Sachs, J. D. (2022). A call for an independent inquiry into the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(21), e2202769119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2202769119

One can search through various different databases, and one is unique to patents in BLAST. Therefore, in order to search through that database one must actively select for that database to choose from. What led the researchers to instinctively check that database is where I raise questions.

So I also didn't include that the apparent relationship to MSH3 and this mysterious sequence was based on amino acid sequence homology, and not the nucleotide sequence. This itself also causes a lot of issues since many (MANY) amino acid sequences will be similar across many species. You can do a BLAST search of the 6 amino acids to find similarities. This also seems improper since you would only include 6 amino acids and leave 1 nucleotide absent, unless the researchers went further and included MORE than the 6 amino acids coded by the 19 (18 actually) nucleotide sequence, and at that time it's really a circular search.

Modern Discontent, I absolutely love your article, even though, admittedly, some paragraphs were above my head.

The sequence in question is indeed short. It is also extremely deserving to be where it is in Sars-Cov-2, where it leads to furin cleavage, infectivity, and pandemic potential.

It is, perhaps not "natural", but perfectly appropriate for a sophisticated researcher to add that sequence to Sars-Cov-2 for a specific purpose (infectivity and pathogenicity).

But why is it in the Moderna MSH3 patent?