At this point none of us should be naïve to the massive uptick in many different diseases. There have been many reports of rising hepatitis, gastroenteritis, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections not only the US, but all around the globe.

Peter Nayland Kust of All Facts Matter has consistently been covering the rise in hepatitis and gastroenteritis cases. The most recent article of his can be seen below:

This has raised questions as to what could really be causing this massive uptick in diseases. For me, I initially considered that this could be a consequence of lack of exposure to pathogens which left many- predominately children- vulnerable to future infections.

But then a few days ago I came across this news report from a Texas news station in which the reporters made the same remarks:

https://www.cbsnews.com/dfw/video/viruses-seem-to-be-back-with-a-vengance/

Unfortunately I can’t embed the video, but the video reports on Cook Children’s ER being inundated with children sick from all different types of diseases including COVID, hand, foot and mouth disease, and RSV.

What’s interesting is that the doctor being interviewed makes a comment that most children’s immune systems are likely fine- they are just catching up from the last few years.

Essentially, children are likely getting more sick because their immune systems have not been properly exposed to pathogens for the past two years due to social distancing, masking, and constant disinfecting.

We even saw evidence of this occurring early on where non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) were praised for not only slowing down the spread of COVID (which is a a rather tenuous assumption at best) but also the seasonal flu.

Because of this lack of exposure and training, children are now catching up on years prior, but unfortunately this is occurring all at once and likely accounts for the higher than normal rates of infection compared to prior years.

This catch-up up on immunity has been referred to as immunity debt, and just like the term implies there is a deficit in these children’s immunity which they are paying back now that most NPIs have been removed and more social interactions are occurring.

The term was first used in a May 2021 article by Cohen, et. al, 20201.

The Abstract states the following (emphasis mine):

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, reduced incidence of many viral and bacterial infections has been reported in children: bronchiolitis, varicella, measles, pertussis, pneumococcal and meningococcal invasive diseases. The purpose of this opinion paper is to discuss various situations that could lead to larger epidemics when the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) imposed by the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic will no longer be necessary. While NPIs limited the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they also reduced the spread of other pathogens during and after lockdown periods, despite the re-opening of schools since June 2020 in France. This positive collateral effect in the short term is welcome as it prevents additional overload of the healthcare system. The lack of immune stimulation due to the reduced circulation of microbial agents and to the related reduced vaccine uptake induced an “immunity debt” which could have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control and NPIs are lifted. The longer these periods of “viral or bacterial low-exposure” are, the greater the likelihood of future epidemics. This is due to a growing proportion of “susceptible” people and a declined herd immunity in the population. The observed delay in vaccination program without effective catch-up and the decrease in viral and bacterial exposures lead to a rebound risk of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Many doctors have raised similar concerns early on- lower childhood vaccination rates and low overall exposure to other pathogens may lead to more harm by limiting the ability for children to produce a robust and broad immune system. It’s a consequence of a global mindset that misses the forest for trees- by focusing on only one pathogen we forget about all the other pathogens that haven’t been a high burden due to modernity and chronic seasonal exposure.

A good outline can be seen below showing the downstream effects of both the pandemic and NPIs (Cohen, et. al. 20212):

Continuing on the authors note the following in their Introduction (emphasis mine):

The current COVID-19 pandemic imposed a number of hygiene measures unprecedented in history (distancing, masks, hand washing, reduced number of contacts, etc.). These personal non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) contributed to limiting the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, but they also reduced the spread of other pathogens. Thus, in hospital emergency rooms and in private practices, the number of visits for community-acquired pediatric infectious diseases decreased significantly, not only during the lockdown periods [1] but also beyond, despite the re-opening of schools [2]. This includes numerous diseases such as gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis (especially due to respiratory syncytial virus), chickenpox, acute otitis media, non-specific upper and lower respiratory tract infections, and also serious ones such as invasive bacterial diseases. These severe diseases due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae b or Neisseria meningitidis are also associated with mucosal carriage and human-to-human transmission through the respiratory tract. Conversely, no decrease in the number of reported cases of Streptococcus agalactiae or urinary tract infections was reported between January and June 2020 compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. This confirms that the reduction in reported S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and N. meningitidis invasive diseases in 2020 reflects true decreases in incidence rather than underreporting [3]. This is not surprising because the transmission modes of these pathogens are often the same as those of SARS-CoV-2 (essentially by large droplets, aerosols, and hands), often with a lower transmissibility for many of them (based on lower R0). Personal NPIs imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic were thus able to slow down transmission and contagion, and therefore disease incidence. This positive collateral effect in the short term is welcome as it prevents additional overload of hospital emergency rooms, wards, and intensive care units during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. However, triggers of these invasive infections are early childhood infections, most often viral, which are almost unavoidable in the first years of life. A lack of immune stimulation due to personal NPI induces an “immunity debt” and could have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control. Mathematical models suggest that respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and possibly influenza epidemics may be more intense in the coming years [4]. Finally, through the possible role of “trained” innate immunity in the defense against infections and a possible return of the hygienist theory, other consequences could be observed. For some of these infections, negative consequences could be balanced by vaccinations (reinforcement of compliance with immunization programs in place, or even widening of vaccination target populations).

The rest of the review article goes into closer detail about specific viral and bacterial infections, but the ideas are the same: isolation led to an overall reduced infection rate across many different pathogens which may see a dangerous rebound effect.

The more important sub-headline is the one referring to immunity debt and trained immunity (emphasis mine):

Children seem to be less often infected with SARS-CoV-2 than adults and present with less severe forms than adults [45]. Various hypotheses have been raised to explain this relative resistance of children to SARS-CoV-2: less ACE2 receptors, frequency of infections with common coronaviruses likely to induce cross immunity, role of trained innate immunity [46]. Indeed, one of the first lines of natural defense against pathogens is the innate immunity which role is to produce an immediate, rapid but non-specific response to an infectious aggression (phagocytosis, production of cytokines, etc.) and which effectiveness has limits. The immune system also develops an adaptive immune response, specific to the pathogen, allowing more effective protection during subsequent exposure to the same pathogen thanks to the development of an immune memory. In recent years, several studies suggested that frequent stimulations and “training” of innate immunity would increase its effectiveness [47]. This stimulation by exposure to various pathogens is undoubtedly more frequent in children than in adults. The concept of trained immunity corresponds to a kind of long-term functional reprogramming of innate immune cells, stimulated by pathogens and which would lead to a reinforced response during subsequent exposures. This process would have great advantages for host defense. Thus, this trained immunity would be established in children particularly exposed to viral infections in the first years of life and would be more effective in them than later in adulthood. The probable role of live vaccines, administered in childhood, on this trained immunity is being studied. The reduction of infectious contacts secondary to hygiene measures imposed by the pandemic may have led to a decreased immune training in children and possibly to a greater susceptibility to infections in children.

The main concept here is one similar to the hygiene hypothesis. Although controversial, the hygienist hypothesis suggests that children raised in more rural, unsterile environments tend to have lower rates of allergies, asthma, and overall illness, suggesting that constant exposure to pathogens is essential to training the immune system. Indeed, the immune system needs to be made antifragile at an early age.

I made similar sentiments in one of my prior posts:

And as I mentioned in this prior post there was a now retracted preprint in which Hong Kong researchers noted a rise in more severe cases of COVID among children. Strangely, the article was an example of doublespeak, in which the authors praised Hong Kong for its rigorous lockdown procedures while also noting that the abundance of NPIs may have prevented children from being exposed to seasonal coronaviruses. It could be that lack of cross-reactive immunity to coronaviruses left many of these children vulnerable to COVID when borders and international travel eventually resumed.

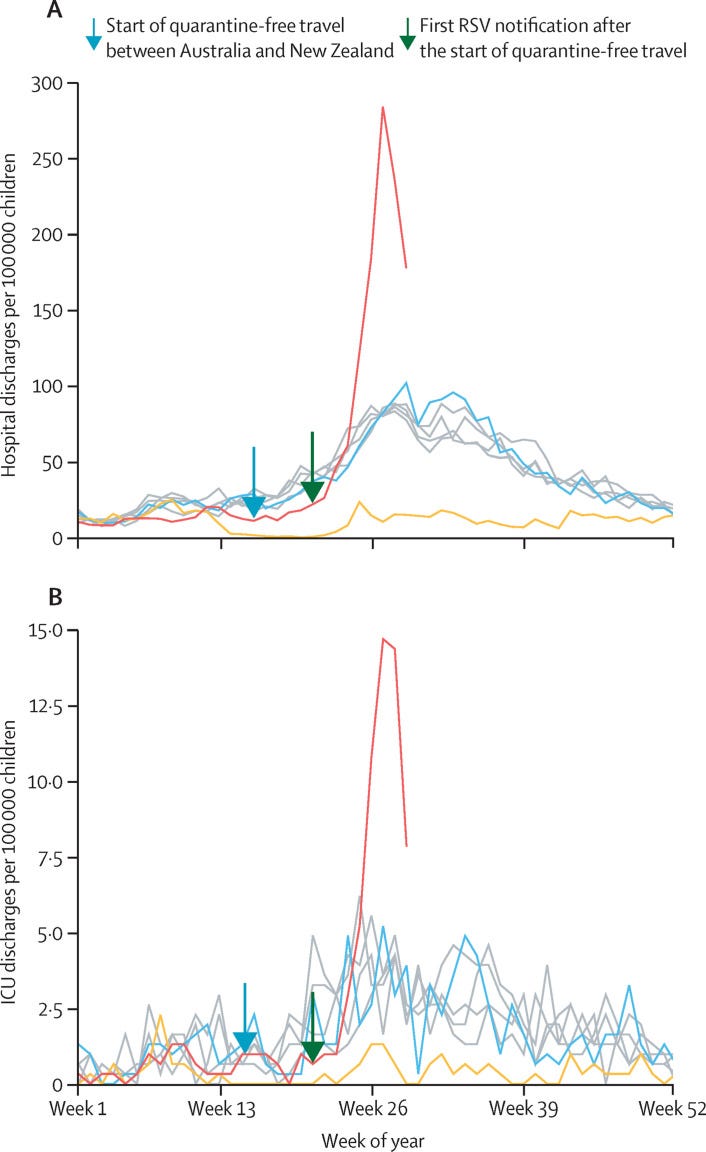

And as stated earlier, this consequence of lockdowns and sterility can be seen in New Zealand with RSV (Hatter, et. al.3, emphasis mine):

New Zealand had very low levels of RSV infection in 2020,3 with no seasonal epidemic of hospital admissions for bronchiolitis (figure ). A partial relaxation of New Zealand's strict border closure policy in April, 2021, to allow quarantine-free travel between Australia and New Zealand, was followed by a rapid increase in RSV cases in New Zealand and hence an increase in admissions due to bronchiolitis. At the peak (week 28, 2021), RSV surveillance numbers were more than five times the 2015–19 peak average.6, 7 Provisional national data for children aged 0–4 years show that in 2021 there were 866 hospital discharges for bronchiolitis during week 27 (bronchiolitis peak); an incidence rate of 284 per 100 000 children in this age group, which was three times higher than the average of peaks in 2015–19. A similar increase was seen in intensive care unit (ICU) discharges for bronchiolitis, with an incidence rate of 15 per 100 000 children aged 0–4 years, which was 2·8 times higher than the average of peaks in 2015–19. These similar rate increases in hospitalisation and ICU discharges suggest that although there was more disease, it was not more severe than in previous years.

So once again we are seeing the consequences of isolation and lockdowns, only now it is playing out in real time. These measures never made sense for a virus such as COVID with a high transmission rate and low case-fatality rate, and yet the entire world was made to participate in a game of political theater, of which we are now reaping the devastating consequences.

It’s a rather ironic turn of events. Many generations tend to blame the faults they experience on generations that came before them. The lack of good-paying jobs, high inflation and massive national debts can be be attributed to generations prior who may have levied future generations for their own selfish needs, and yet we are now seeing this play out with respect to immunity debt.

It’s a result of what happens when somewhat well-intentioned ideas fail horribly in practice. Sure, we may raise concerns about the immunocompromised- it’s been one of the biggest talking points in pushing for lockdowns. Yet we are seeing a paradoxical effect, in which the concerns raised over the immunocompromised have ironically caused all of us, especially children, to become immunocompromised ourselves. The concerns over the susceptible bubble boy has caused us all to attempt to live in our own sterile bubbles, and just like monetary debt our bubbles of sterility and cleanliness are beginning to burst.

The early years of childhood are the most formative years. Social interactions, education, and immunity training all help prepare children for the future. Children start naïve and fragile, yet it’s through adversity that these children are made antifragile and capable of taking on the world. Unfortunately, it seems that we have failed children in all avenues since the coming of COVID.

And as cases of various infections continue to climb all across the world, we may have to live with the fact that we have once again failed the younger generations4. They were not prepared properly due to the fears and anxieties- mostly unfounded and pushed by the media- from those who should have known better; those whose job it is to make sure children become antifragile and can overcome their own challenges.

Unfortunately, it’s a little too late for that now in regards to COVID, but let this be a lesson for the future as to what happens when we miss the forest for the trees and give into histrionics and fear, because our children’s wellbeing depends on it.

Cohen, R., Ashman, M., Taha, M. K., Varon, E., Angoulvant, F., Levy, C., Rybak, A., Ouldali, N., Guiso, N., & Grimprel, E. (2021). Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap?. Infectious diseases now, 51(5), 418–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004

Cohen, R., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., Somekh, E., & Levy, C. (2022). European Pediatric Societies Call for an Implementation of Regular Vaccination Programs to Contrast the Immunity Debt Associated to Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic in Children. The Journal of pediatrics, 242, 260–261.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.11.061

*This article is similar to Cohen’s prior article but provides some more context due to updated epidemiological evidence collected from many European countries.

Hatter, L., Eathorne, A., Hills, T., Bruce, P., & Beasley, R. (2021). Respiratory syncytial virus: paying the immunity debt with interest. The Lancet. Child & adolescent health, 5(12), e44–e45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00333-3

Being a millennial I really don’t know where my hand is in the matter, but I just decided to use a more generalized term when referring to older/younger generations.

First we raised emotionally and/or intellectually fragile children & now we are raising immunologically fragile children - seems our progeny are doomed (which I don’t doubt they are from our unsustainable federal bureaucracy - which differs vastly from the reasons for which they believe they are doomed).

Growing up in the 80’s was great! Even though we were generally rather poor when I was little my parents risked everything on a business and through their hard work & perseverance they made it prosper. I am painfully aware of their sacrifices and have personally benefited greatly from their success. I do not take that for granted. Now we do not generally struggle, but I worry about my daughter’s ability to struggle - it’s so difficult to get her to do “hard things.” But, thankfully I don’t worry about her immune system as we spend lots of time outside digging in dirt.

The immunity debt is a good way to conceptualize the seeming overall uptick in disease burden.

While the lockdown and social isolation protocols of "Zero COVID" almost certainly play a role here, I see a growing probability that the COVID inoculations are also a contributing factor.

(And thanks for the mention!)