Ozempic and vision loss?

New evidence points towards another concerning side effect related to these GLP-1 RAs, and one that seems somewhat unrelated to the drug's mechanism of action.

A few weeks ago a concerning study was published alleging an increased risk of vision loss in those who take Semaglutide called Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy, or NAION1.

This would add to the growing body of evidence suggesting various adverse events related to these growingly popular medications.

However, at the time of this study’s publication I didn’t pay it much attention, mainly because the condition in question here seemed peculiar relative to how the GLP-1 RAs are alleged to work.

For instance, in previous writings I wrote that GLP-1 slows down digestion by reducing stomach and intestinal contractions, the consequence of which includes feelings of satiety. This is one of the mechanisms by which GLP-1 RAs induce weight loss by producing feelings of satiety for longer, and thus reducing eating.

However, in some individuals it appears (although has not been elucidated) that a possible hypersensitive/hyperresponsiveness to GLP-1 RAs may cause an overexaggerated slowing of the intestines and stomach, likely resulting in paralytic conditions such as gastroparesis (stomach paralysis) as well as ileus (intestinal paralysis).

In those cases we can see a clear association between a drug’s mechanism of action and the relationship with an adverse event.

Here, the association isn’t quite clear. Exactly what relationship would GLP-1 have with the eyes? And why would researchers consider such an association to begin with?

The last question is fairly relevant to this study. Usually, one would consider that a researcher provide some reasoning for their hypothesis formation.

Here, the author’s don’t provide any reason for why they chose to look into NAION aside from “anecdotal experience”:

Anecdotal experience raised the possibility that semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) with rapidly increasing use, is associated with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION).

Curious why such an ambiguous statement was used to catapult such a study, and given the amount of uncertainties related to these GLP-1 RA medications any additional context would help create better understanding for what these drugs are doing within our bodies.

Nonetheless, the study itself is rather uneventful. Researchers examined referrals to neuro-ophthalmology clinics between the time periods of December 2017-November 2023:

The number of unique patients who had been referred for any presumed neuro-ophthalmology indication and evaluated in our neuro-ophthalmology clinic from December 1, 2017, through November 30, 2023, was determined from the MGB centralized clinical data registry and composed our eligible cohort.

Patients were identified for confirmed cases of NAION, and were then categorized based upon Type II Diabetes and overweight/obesity status in order to create independent cohorts. Patients who were taking Semaglutide were matched with patients on non-GLP-1 RAs and assessed for events of NAION within the years following medication prescription.

An outline of the study design can be seen below for better context:

Interestingly, researchers noted a stark difference in NAION events between the two groups, such that those within the Semaglutide group had far higher events of NAION relative to non-GLP-1RA users.

Even more interesting is the fact that these events of NAION appeared to occur predominately within the first 12 months of a Semaglutide prescription.

This effect was present in both the Type II Diabetes as well as the overweight/obesity cohorts:

In essence, there appeared to a 4-fold risk of developing NAION in Semaglutide patients with diabetes relative to non-GLP-1 RA users, and an 8-fold risk of developing NAION in Semaglutide patients who are overweight/obese relative to non-GLP-1 RA users:

The relatively high HRs (4.28 and 7.64 for our T2D and overweight or obese cohorts, respectively) identified by our Cox regression analyses reveal a substantially increased risk of NAION among individuals prescribed semaglutide relative to those prescribed other medications to treat T2D and obesity or overweight. This risk appears not to be due to differences in baseline characteristics between the cohorts.

Now, there’s a few things to point out regarding this study:

The authors don’t make a distinction between the source of Semaglutide among the patients. This is a concern given recent findings that people prescribed compounded Semaglutide may not be adequately informed on dosing instructions, thus leading to excessive Semaglutide administration. Granted, this concern could be buffeted by the timing of this study, as it’s likely that many of the doses reported in this study are from brand-named Semaglutide products. Nonetheless, better clarity on Semaglutide sourcing should be encouraged in studies.

There also isn’t any information regarding the additional medications that these patients may be on. The information regarding non-GLP-1 RA is itself ambiguous, as there isn’t any indication regarding what type of non-GLP-1 RA theses patients are taking, and if combinations of medications may be administered. Remember that obesity and diabetes themselves increase the risk of developing comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and other maladies. Again, lack of clarity in prescription background leaves a lot of unnecessary gaps in information.

There’s no elaboration on the strange prevalence of NAION within the first 12 months of prescribing Semaglutide. This is a rather important finding that could suggest possible drug tolerance, or attenuation of some factor that may make one more prone to developing NAION. We’ll elaborate on the last point further below.

So, from what can be gathered from this study we have another side effect related to the use of these GLP-1 RAs, and as mentioned by the authors the more people who are prescribed these medications the more likely that NAION events are to be reported.

That being said, what still remains unanswered is what the exact link between Semaglutide use and NAION could be. It’s a shame the authors don’t provide any background regarding their exploration into this relationship, and for many people this association may not seem to important.

However, as someone interested in mechanism this lack of context is insufficient, and in fact isn’t quite helpful for those who would like to find answers for their NAION development. It certainly doesn’t help clinicians who may not know what to look out for in order to determine risk of NAION development for any patients who choose to go onto Semaglutide or other GLP-1 RAs.

Therefore, in this absence of information I found it fitting to at least see what the literature says and see what we can piece together to try to form our own hypothesis regarding this Semaglutide/NAION relationship.

What is NAION?

First, it’s important to explain what NAION is and the underlying pathophysiology.

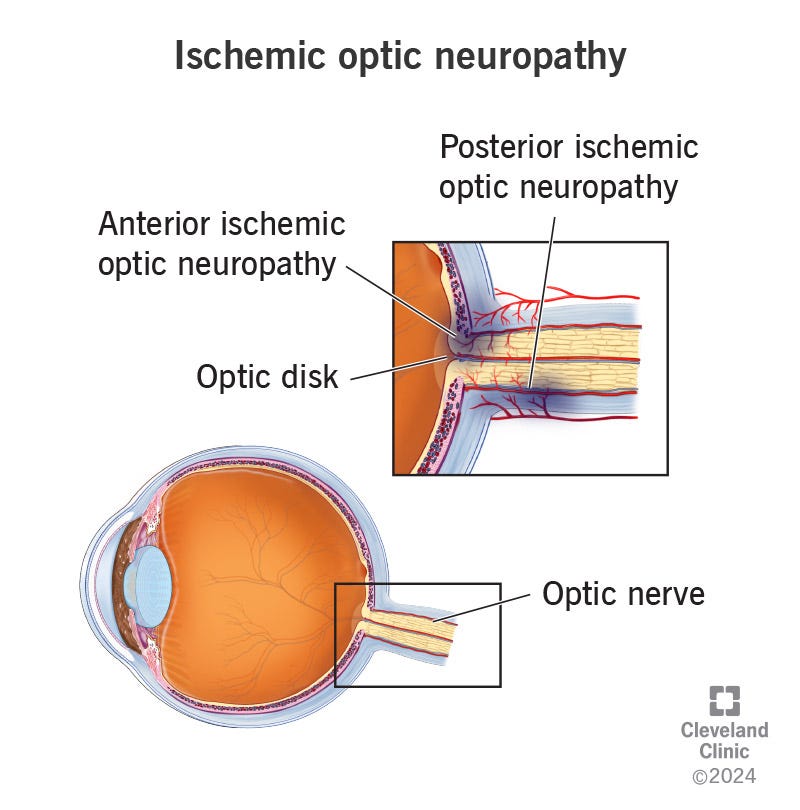

NAION is one of the most common causes of optic nerve injury and vision loss for those over the age of 50. It’s generally painless and acute, and it falls under the umbrella of Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. ION is categorized based upon the region of the eye in which complications are occurring:

anterior ION refers to issues around the optic disk region of the eye- an area in which blood vessels and neurons attach to the eye.

posterior ION refers to issues deeper/along the optic nerve.

Remember that the focus for this article is on NAION.

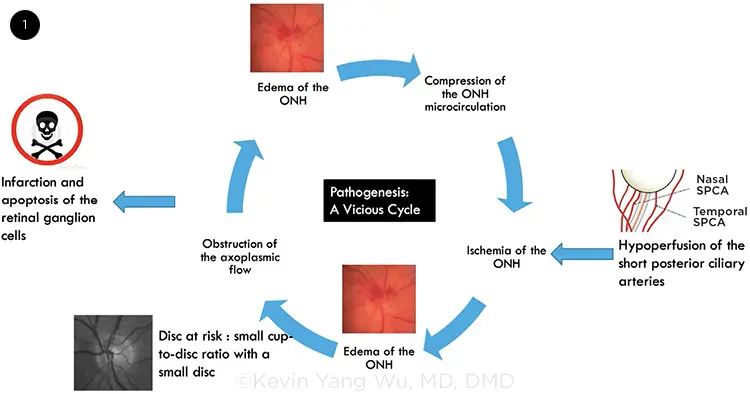

The underlying pathogenesis of NAION is generally unknown in most cases. However, the leading hypothesis suggests that NAION may be a result of improper blood flow to the eye2:

While the exact pathogenesis of a NAION has not been elucidated, the prevailing theory is that it is caused by hypoperfusion of the short posterior ciliary arteries supplying the optic nerve, which then causes ischemia that induces swelling of the portion of the optic nerve traveling through the small opening in a scleral canal.[2] This, in turn, leads to the compartment syndrome involving neighboring axons that are now compressed in a space limited by the small opening in the scleral canal, leading to apoptosis and death of the ganglion cells whose axons comprise the optic nerve.

In essence, blood flow to the eye gets reduced (ischemia), leading to lack of oxygen (hypoxia) and nutrients within the area. Axons then respond by swelling, which creates a feedback known as compartment syndrome in which swelling of the axons further cuts off blood flow to the eye and therefore exacerbating the problem.

If prolonged, cells within the area begin to undergo apoptosis, with the end result being vision impairment.3 Usually loss of vision is unilateral, meaning only one eye may experience blurred vision. And although NAION is said to occur acutely, the event may progress over the course of several days.

Now, readers may be curious- if there is a NAION then is there AION (Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy)? Indeed there is, with the difference involving inflammation of the arteries in the case of AION.

Symptoms are quite different for AION as compared to NAION. Both tend to result in vision loss or color discoloration. However, where NAION is generally painless AION is generally painful due to the arteritis involved, and can result in headaches or muscle pain from chewing.

Unfortunately, vision loss from NAION can remain permanent. Some patients appear to regain some vision over time, but in most cases vision remains perturbed following a NAION event. Furthermore, there doesn’t appear to be any viable treatments for NAION, and general suggestions for managing NAION involves managing the underlying conditions that can contribute to further NAION development, or to manage underlying conditions in order to prevent a NAION event from occurring in the first place.

With that, several underlying conditions can contribute to increased risk of NAION, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, smoking, and obstructive sleep apnea. Medications may also contribute to increased risk of NAION. In general, factors related to blood circulation tend to be variables worth considering with respect to NAION, and in many cases it’s likely that NAION risk is exacerbated by a combination of factors.

What’s rather interesting is the fact that recognition of vision loss related to NAION tends to occur after waking up. This may seem rather surprising at first, but this can be explained due to the decrease in blood pressure that occurs at night (nocturnal hypotension), which may result in ischemia and hypoxia of the optic disc region.

This appears to have a led to some controversy regarding the administration of antihypertensives at night, as the reduced risk of nocturnal cardiovascular events may be counteracted by increased risk of NAION.4

Is there a relationship between Semaglutide and NAION?

Now, it’s time to return to the prevailing question- is there a relationship between Semaglutide use and risk of NAION development?

Such a question is difficult to answer, and we have to rely on the scant information available to try to come up with some direction to look.

So far we have outlined that NAION is predominately a condition related to reduced blood flow/pressure to the eye made evident through the association between NAION and other factors related to blood circulation. Even more evident is the fact that NAION tends to occur during wake up, which follows nocturnal dips in blood pressure. All of this at least serves as a starting point to examine with respect to Semaglutide.

As in, does Semaglutide reduce itself blood pressure?

To answer such a question we should obviously consider the possibility that Semaglutide as an obesity/diabetes medication may peripherally influence blood pressure by way of attenuating the former maladies. Therefore, it’s going to be rather difficult to parse out independent effects of Semaglutide on blood pressure, and readers should take that into consideration when looking at the available information.

That being said, several lines of evidence point to Semaglutide having a hypotensive effect, with the greatest lines of evidence being one meta-analysis which examined a reduction in systolic blood pressure of ~4.85mmHg in patients who were overweight but did not have diabetes.5 Another systematic review/meta-analysis looking at studies with Type II diabetics also noted a decrease in systolic blood pressure with Semaglutide use, albeit with a smaller effect of 2.31mmHg decrease.6

It’s important to remember that such meta-analyses likely included studies that utilized different Semaglutide doses, as well as patients with different clinical backgrounds including comorbidities or medicine use.

Nonetheless, this does provide some evidence that Semaglutide can reduce blood pressure.

Now, how this translates to NAION is a whole separate question. One possibility could lie in the nature of nocturnal hypotension in a subset of patients. Although people generally experience a reduction of blood pressure while sleeping some individuals may experience an over-exaggerated response, in which a much greater dipping of blood pressure may occur (sometimes termed as “dippers” or “exaggerated” responses). This is made evident by a prior study which noted a far lower dip in blood pressure among those with NAION relative to those without, although these findings seem to be contradicted by additional studies (summary below from Salvetat, et al):

Nocturnal systemic arterial hypotension: considering that the acute vision loss at NA-AION presentation is noticed upon awakening in more than 70% of cases [52], it is suggested that nocturnal hypotension could be a precipitating risk factor for NA-AION, especially in so-called “deeper” subjects, i.e., subjects in which the physiological nocturnal hypotension occurring during sleep, due to the attenuation of the sympathetic tone, is significantly higher than in normal subjects; or in patients assuming anti-hypertensive medications at night. The effective role of the nocturnal systemic hypotension remains unclear and controversial. Comparing the 24 h blood pressure data amongst NA-AION, POAG and NTG patients, Hayreh et al. suggested that nocturnal systemic hypotension may have a role in the development of NA-AION in susceptible subjects [55]. On the other hand, Landau et al. [56] compared the 24 h blood pressure in NA-AION and controls matched for age, associated disease, and medications, and found a similar nocturnal decrease in blood pressure in the two groups, but a slower morning rise in pressure in NA-AION patients, that could explain the typical presentation of NA-AION upon awakening;

To put this into perspective, the hypotensive effects of Semaglutide may be mild, but in some individuals the effect may be even more pronounced and the hypotensive effects greater. Because Semaglutide is administered weekly we can argue that Semaglutide will continuously circulate in an individuals body, only attenuating near the end of the week when one is near their next dose.

Some individuals may also experience wide variations between daytime and night-time blood pressure levels. Ironically, this is argued to be a reason for the paradox of people with hypertension being at risk of NAION, as hypertensive individuals may see larger dips in blood pressure relative to non-hypertensive individuals.

Altogether, the combination here may make for a perfect scenario in which the combination of nocturnal hypotension and the hypotensive effects of Semaglutide may be enough to pose a risk for developing NAION.

Of course, all of this is mere speculation, and unfortunately there was less information to work with than I had hoped when writing this post.

Regardless, it’s more than what was provided by the authors, and it at least tries to draw a relationship between Semaglutide and this strange, rare condition.

There’s still a lot that is unknown about these medications, but what’s concerning is that we are learning about concerning side effects while more and more people are being prescribed these medications.

There’s a ton that is still not known, and rather than argue that these medications are “safe and effective” for everyone we should hesitate until more information comes out.

This is one example of a place in which we see a possible side effect that seems tangential to the medication in use, which should raise some important questions trying to tie the relationship together.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Bear in mind that some abbreviations may use an additional A to form NAAION or NA-AION. I will use NAION consistently in this article as this is the abbreviation used by the authors.

Raizada K, Margolin E. Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. [Updated 2022 Oct 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559045/

A more concise definition can be found from Salvetat, et al.:

The term “ischemic optic neuropathy” has been used in the medical literature for many years to describe conditions involving inadequate blood supply to the optic nerve, leading to vision loss. “Non-arteritic” in NA-AION refers to the fact that this condition is not associated with inflammation of the arteries (as in arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy or AAION). “Anterior” indicates that the damage occurs in the front portion of the optic nerve, closer to the eye. “Ischemic” underscores the central mechanism of NA-AION, which involves a restriction of blood flow to the optic nerve. “Optic neuropathy” denotes the involvement of the optic nerve, which connects the eye to the brain and is crucial for vision. Understanding the historical context and the terminology surrounding NA-AION is essential to understand its development as a distinct clinical entity and its place within the broader field of ophthalmology and neurology.

Salvetat, M. L., Pellegrini, F., Spadea, L., Salati, C., & Zeppieri, M. (2023). Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (NA-AION): A Comprehensive Overview. Vision (Basel, Switzerland), 7(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040072

Labowsky, M. T., & Rizzo, J. F., 3rd (2023). The Controversy of Chronotherapy: Emerging Evidence regarding Bedtime Dosing of Antihypertensive Medications in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Seminars in ophthalmology, 38(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08820538.2022.2152709

Kennedy, C., Hayes, P., Salama, S., Hennessy, M., & Fogacci, F. (2023). The Effect of Semaglutide on Blood Pressure in Patients without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 12(3), 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030772

Wu, W., Tong, H. M., Li, Y. S., & Cui, J. (2024). The effect of semaglutide on blood pressure in patients with type-2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine, 83(3), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-023-03636-9

THIS goes AGAINST the natural body! How can any “doctor” prescribe this? It’s an absolute travesty!

I went to the “medical cartel” for a prescription I do need (I know), and this Ozempic has an insert of “two encyclopedias”! The “nice” brochure was in the “doctor’s” office.

I took pics…I wish I could post it…INSANE!

I’m rather sure I read/heard recently that FDA wants to approve Ozempic for obese children as young as 6 years old.... does the nightmare ever end...?