Oral Phenylephrine probably should have never gotten approval.

Maybe part of the focus should be on auditing the FDA for past drug approvals...

A few days ago the FDA issued remarks on oral Phenylephrine and the lack of evidence suggesting it may reduce nasal congestion:

[9/14/2023] FDA held a Non-prescription Drug Advisory Committee meeting Sept. 11-12, 2023, to discuss the effectiveness of oral phenylephrine as an active ingredient in over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold products that are indicated for the temporary relief of congestion, both as a single ingredient product and in combination with other ingredients.

The committee discussed new data on the effectiveness of oral phenylephrine and concluded that the current scientific data do not support that the recommended dosage of orally administered phenylephrine is effective as a nasal decongestant. However, neither FDA nor the committee raised concerns about safety issues with use of oral phenylephrine at the recommended dose.

For those willing to sit through the entire 8-hour panel here’s the livestream from which the FDA’s summaries are derived from:

The past few years have left the public with a lasting negative perception when it comes to these federal agencies and their approval processes. The COVID vaccines and biased invocation of EUA approvals should have been enough evidence.

However, the recent remarks with respect to Phenylephrine introduce a rather interesting conundrum, as prevailing evidence from the past few years have raised serious questions as to the actual effectiveness of oral administration of Phenylephrine in dealing with nasal decongestion.

And so, rather than being a question of the FDA removing a product with known efficacy, the real question is how such a product made its way into the many OTC medications.

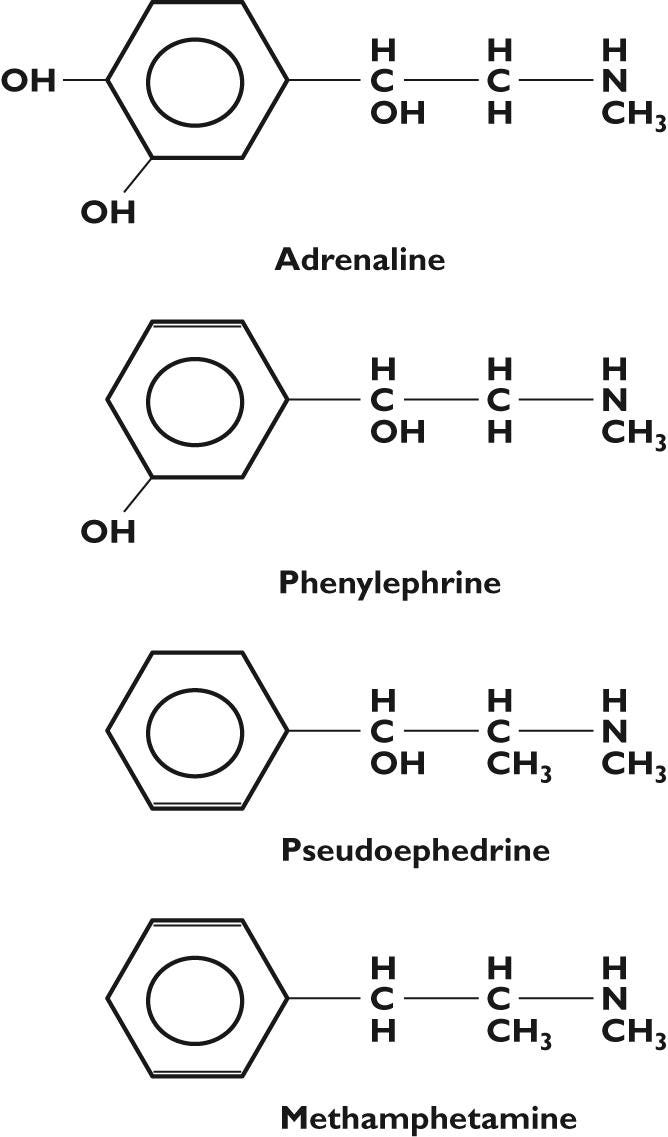

Phenylephrine is one of a series of drugs designed to look structurally similar to adrenergic compounds such as epinephrine (adrenaline) or norepinephrine, and are intended to induce adrenergic agonistic effects by way of activating the sympathetic nervous system.

With respect to their roles as decongestants the use of these compounds are intended to induce vasoconstriction, reducing edema/inflammation within the nasal passages by way of binding to adrenergic receptors.

Note that Phenylephrine only differs from adrenaline by the removal of one -OH group from the aromatic ring. In contrast, Pseudoephedrine, another commonly used decongestant, bears an additional methyl group (-CH3) while also bearing no -OH groups on the ring structure.

Pseudoephedrine gets its prefix by way of its stereochemistry, in which the molecular structure of Pseudoephedrine is the same as ephedrine with the only difference being the orientation of the -OH group (differences noted by dashes and bold lines1):

Pseudoephedrine was a mainstay for many OTC nasal decongestants. However, as the “war on drugs” raged on the use of Pseudoephedrine in the production of Methamphetamine raised serious concerns about this compound’s wide availability, leading pharmacists and drug stores in some areas of the US to limit its over-the-counter availability around the early 2000’s. However, in 2006, the Combat Methamphetamine Act of 2005 signed by then President Bush as part of the Patriot Act eventually led to a nationwide restriction on medications which contain Pseudoephedrine, Ephedrine, and/or Phenylpropanolamine from being widely accessible, relegating them to behind pharmacy counters instead of being purchasable over-the-counter:

The Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 has been incorporated into the Patriot Act signed by President Bush on March 9, 2006. The act bans over-the-counter sales of cold medicines that contain the ingredient pseudoephedrine, which is commonly used to make methamphetamine. The sale of cold medicine containing pseudoephedrine is limited to behind the counter. The amount of pseudoephedrine that an individual can purchase each month is limited and individuals are required to present photo identification to purchase products containing pseudoephedrine. In addition, stores are required to keep personal information about purchasers for at least two years.

Although a prescription wasn’t required to obtain medications containing Pseudoephedrine, the record-keeping and barriers for accessibility greatly limited the use of these medications.

In contrast, Phenylephrine began seeing wider use and inclusion in many cold and allergy medications, and is widely available in hundreds of different medications as of this day.

And yet, evidence of Phenylephrine’s effectiveness as a nasal decongestant has always been questionable, with evidence pointing towards possible influences by pharmaceutical representatives in Phenylepherine’s touted effectiveness, as reported in Eccles, R.2:

No support has been found in the literature in the public domain for the efficacy of PE as a nasal decongestant when administered orally. Approaches to the UK and USA regulatory authorities (MHRA and FDA) have not provided any information in the public domain. The 1976 FDA monograph on OTC cold and cough products reports that PE is an effective nasal decongestant on the basis of reports on in-house studies on PE provided by representatives of pharmaceutical companies [18]. On the basis of these in-house studies, the FDA approved PE as an effective nasal decongestant. This decision by the FDA on the efficacy of PE was questioned by a comment to the FDA in 1985, which stated that the unpublished studies split evenly between mild successes and total failures; in addition, the comment questioned the oral bioavailability of PE and recommended that the FDA should not accept PE as an oral decongestant [19]. Despite the concern expressed about the efficacy of PE as an oral decongestant, the FDA maintained its approval for PE as an effective nasal decongestant and PE is accepted as an effective oral nasal decongestant in the FDA's final conclusions on nasal decongestants published in 1994 [20].

So it appears that even at the time of this 1976 FDA monograph the effectiveness of oral Phenylephrine as a nasal decongestant was up in the air, and yet still was argued to be effective by the FDA, finding a perfect fit in the post-Patriot Act era.

Remember that we are looking at oral use of Phenylephrine here. When thinking about the pharmacokinetics of drugs keep in mind that the way that a drug is administered affects dosing as well as metabolism of said drug.

For instance, Phenylephrine has been used in eye drops and intravenously. Evidence even suggests that the use of Phenylephrine as a nasal spray may help with nasal decongestion in contrast to oral administration, all of which points to issues in metabolism and likely the first-pass effect of oral Phenylephrine.

Indeed, unlike Pseudoephedrine, Phenylephrine is readily metabolized within the gut and intestines, owed largely in part to enzymes such as monoamine oxidases, P450 enzymes of the liver, and other metabolic enzymes.

As such, the bioavailability of oral Phenylephrine is extremely low, with many of the metabolites also appearing inert (technically termed “not pharmacologically active”), suggesting that hardly much of the intact Phenylephrine actually makes its way into the bloodstream and to the nasal passages where it is expected to induce its pharmacological effects (Eccles, R.):

Both PE and PDE are well absorbed from the gut. The main difference between the decongestants is that after oral administration PE is subject to extensive presystemic metabolism by monoamine oxidase in the gut wall [10, 13]. As a consequence of metabolism, systemic bioavailability of PE is only around 40% [13]. Only about 3% of an oral dose of PE is excreted unchanged in the urine [10]. PDE is resistant to the actions of monoamine oxidase and between 43% and 96% of an oral dose is excreted unchanged in the urine [10].

Monoamine oxidases are a class of enzymes involved with the metabolism of catecholamines such as dopamine and adrenaline. In that regard, I would hypothesize that the phenyl -OH of Phenylephrine is necessary for monoamine oxidases to recognize this drug, in contrast to Pseudoephedrine which lacks any -OH group on the aromatic ring and therefore likely goes undetected by these enzymes.

Overall, all of this likely suggests that the dosage of Phenylephrine found in OTC oral formulations are likely drastically below anything that would produce a pharmacological effect, and in essence is inherently ineffective at serving as a nasal decongestant even though they have been in common use for decades and widely available to the public.

Keep in mind that any formulation for cold symptoms that utilize Phenylephrine will also likely contain antihistamines, which may induce a false assumption that the Phenylephrine in these products are actually doing their job.

I haven’t listened to much of the committee hearing, but I did come across this little snippet, in which it was commented that use of nasal sprays containing Phenylephrine may lead to a million fold higher dosage relative to the Cmax (the highest concentration a drug achieves within the bloodstream) in a typical 10 mg oral formulation of Phenylephrine.

This doesn’t mean that nasal sprays are overdosed, but rather emphasizes the fact that oral administration of Phenylephrine leads to hardly any Phenylephrine within the system of individuals taking these drugs.3

This problem also doesn’t seem to be countered by the fact that many OTC cold/allergy medications instruct routine use of these medications throughout the day, as studies carried out to look at higher doses of oral Phenylephrine still showed no efficacy.

For brevity, here is The Atlantic’s summary of these remarks from the committee meeting, referring to additional studies undertaken by Merck to see if higher oral doses of Phenylephrine would show an effect:

In hopes of making an effective product, Merck went to study higher doses in two randomized clinical trials published in 2015 and 2016. “We went double, triple, quadruple—showed no benefit,” Eli Meltzer, an allergist who helped conduct the trials for Merck, said at the FDA-advisory-panel meeting this week. In other words, not only is phenylephrine ineffective at the labeled dosage of 10 milligrams every four hours, it is not even effective at four times that dose. These data prompted Hatton and Hendeles to file a second citizen petition and helped prompt this week’s advisory meeting. This time, the panel didn’t need any more data. “We’re kind of beating a dead horse … This is a done deal as far as I’m concerned. It doesn’t work,” one committee member, Paul Pisarik, said at the meeting. The advisory’s 16–0 vote is not binding, though, so it’s still up to the FDA to decide what to do about phenylephrine.

As reevaluation of Phenylephrine is underway, it’s worth noting that other common OTC compounds are being reevaluated for their efficacy, including Dextromethorphan and Guaifenesin-containing formulations which are argued to act as cough suppressants.4

And so the FDA is in a rather interesting position. Rather than seeing the current debate over Phenylephrine as being a removal of an effective drug, this should be seen as an issue of the FDA’s issuance of efficacy in the first place, especially in lieu of limited data.

It’s quite apparent that even at the time of the 1976 monograph there were questions as to whether oral Phenylephrine actually worked, and yet it was still deemed so with possible help from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

This also comes with the fact that an actually effective nasal decongestant Pseudoephedrine was pulled from shelves in order to deal with a drug epidemic that doesn’t seem to have been properly dealt with.

In fact, as remarked by Derek Lowe in his Science editorial (in response to this piece published in Sage Journals5, whose authors seem to be the same ones involved with the move to get the FDA to have the committee hearing), methamphetamines appear even more widely available and cheaper than ever before [context added]:

This situation obtains, of course, because as mentioned above you can make methamphetamine from pseudoephedrine. There are a number of synthetic procedures for doing this, some of them quite alarming, and several of which can indeed be performed in the barn, garage, basement, or trailer park of your choice - if you can get enough pseudoephedrine. Thus the move to put medications containing this behind the pharmacy counter, with limits on their sale. No more walking in with a duffel bag and buying every single Sudafed package in the store.

But it's quite possible that that era is gone anyway. The Mexican drug cartels have apparently been putting some real effort into process improvements and economies of scale, and I am told that the drug is (sadly) cheaper than it's ever been and available in higher purity than all but the most dedicated basement lab would be able to provide. As that article [Sage Journal article cited above] details, this includes an interesting and concerning increase in the compound's enantiomeric purity over the years. Whatever the current synthesis is - and you can be sure that the DEA knows the details, even if they are understandably not going into them in public - it is strongly skewed towards the more pharmacologically desirable D-methamphetamine. All this means that even if pseudoephedrine were more freely available, it might not be as much of an illegal article of commerce as it was twenty years ago.

Like with every aspect of the war on drugs, this also appears to have been a solution to a problem that continues to exist, with the only real sufferers of these policies being people who may be placed on a list for daring to obtain an actually effective nasal decongestant, as well as people who may have routinely spent money during cold and allergy seasons for medications that really don’t do anything to alleviate their symptoms.

And so, rather than abolish the FDA, it may be more pertinent to encourage audits of the FDA’s approval process. Make the FDA examine prior drug approvals and drug efficacy data to see if there is clear, robust evidence in regards to the benefits of certain drugs rather than rely on the assumption that a drug widely used for decades would be inherently effective. More transparency and better dissemination of information is needed by these agencies who have made themselves the arbiters of our health.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Remember that in organic chemistry the structure of the molecule alone is not enough to infer a compound’s mechanistic properties. The orientation of functional groups is also important. In general, when looking at these structures remember that any normal-looking lines are associated with that portion of the molecule being “flat”, as in being within the same plane of symmetry. In contrast, bold lines infer that the group in question is pointing “towards” you, or “in front of” the plane of symmetry. Dashed lines note groups that are pointed “away” from you or “behind” the plane of symmetry.

For example, the -OH group on Ephedrine is pointing forwards or towards you while the -OH in Pseudoephedrine is pointing away. Although this may seem trivial, this minor change makes Pseudoephedrine a strong nasal decongestant candidate while the decongestant effects of Ephedrine are unknown. Therefore, it’s quite possible that such a minor change in orientation alters the adrenergic receptors that these compounds bind to.

Eccles R. (2007). Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 63(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02833.x

Ironically, the studies conducted to suggest that oral administration of Phenylephrine is severely ineffective was conducted by Schering-Plough, later to be known as Merck (yes, that Merck). As suggested in the article from The Atlantic, then Schering-Plough intended to change their formulating of Claritin-D to include Phenylephrine rather than Pseudoephedrine, and it was due to those studies that they noted the remarkably low bioavailability of Phenylephrine.

Mucinex DM being an example of this type of OTC medication.

Hatton RC, Hendeles L. Why Is Oral Phenylephrine on the Market After Compelling Evidence of Its Ineffectiveness as a Decongestant? Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2022;56(11):1275-1278. doi:10.1177/10600280221081526

Why did the FDA approve it in the first place?

Why does a dog lick its ass?

You don't want your name in a pseudoephedrine log, ever. Period, full stop.