More COVID infections, more death?

A new study suggests that more COVID infections are associated with increased risk of long COVID and death. Is there more to the study than meets the COVID paranoid eye?

*Cover image from the New York Times.

Just yesterday I posted some criticisms of a VA study looking at PAXLOVID in reducing long COVID.

As stated there, that study was a study in a sea of no other studies, and so the modest effects are hard to assess without any other comparative information.

However, the same PAXLOVID long COVID researchers released ANOTHER study using even more data from the VA, published online in Nature just yesterday as well.

Talk about working fast!

Unlike the post on long COVID this study had some horrific (if true) findings.

In essence, reports of this new study draw an association between the number of COVID infections and increased risk of long COVID, death, and hospitalization.

Put another way, the more COVID infections one gets the greater the risk of suffering long COVID and death.

Pretty scary if true, although such findings run counter to some of the previous data on repeat infections.

Dr. Monica Gandhi was quoted within a Washing Post article in stating that there doesn’t appear to be evidence in favor of repeat infections leading to more severe illness:

Monica Gandhi, an infectious-diseases specialist at the University of California at San Francisco, said it is important to keep in mind that research using electronic medical records “does not reliably predict a causal relationship.”

Gandhi pointed to other studies, including one that took a look at 26 studies of reinfections that show they become less severe over time. Another study from Qatar examined patients with different vaccination histories in more comprehensive ways and found that reinfections tend not to progress to severe, critical or fatal outcomes. Those studies have not yet been peer-reviewed.

Gandhi also said there’s research showing that infection, reinfection, vaccination and boosting broaden and diversify components of the immune system that may make people “better able to respond to the newest subvariants as we continue to live with covid-19.”

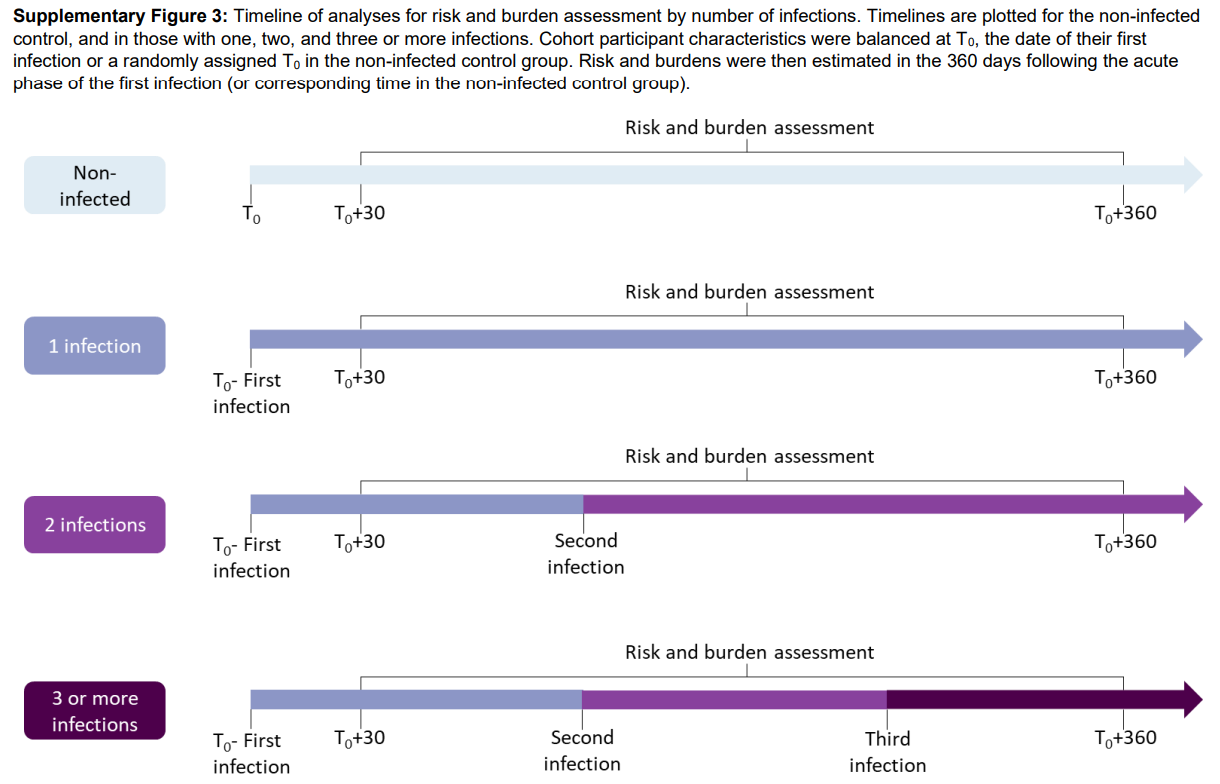

This study looked at health records of millions of VA patients and compared their infection rates across a one year time period since initial infection (noted as T0). Patients included were those who were first infected in the time period between March 1, 2020 until April 2022.

Reinfection in this study was considered an infection that occurred at least 90 days since the previous infection.

A bit confusing, but the following diagram outlines how various infection rates fit into this timeline until the measure of burden, risk, and death. Note that the timeline is very loose, in that someone may have been reinfected 6 months since the first infection, someone could have been infected 3 months after the first and then once again 6 months later, etc. etc. What’s important is to note that risk and burden assessment occurred over a year after the first positive test for the first infection (noted at the T0+360 day mark).

The pertinent graph is the last one from the study, which compared post-acute sequelae and hospitalizations stratified based on the number of infections a VA patient had.

The design and results can be summarized below:

To better understand the cumulative risks incurred by people with multiple infections, we estimated the cumulative risk and burden of a set of prespecified outcomes in those who did not have a reinfection (had only one infection), and those who had two or three or more infections during the 1-year period after the acute phase of the first infection, compared to a noninfected control group. Cohort characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 6. There was a graded association in that the risks of adverse health outcomes increased as the number of infections increased.

As seen in Figure 5 each additional infection seems to increase the risk of suffering from any of the above sequelae, although the leap from one reinfection to a 3rd infection or above is interestingly smaller than the jump from the 1st infection to the 2nd.

Again, this information would be very concerning if true.

However, note that the study here is not a longitudinal study like the one I analyzed a few weeks prior in which participants were followed up with at various timepoints in the study.

Instead, someone who had up to 3 infections did not have measurements of their health and any PASC taken after each infection, but instead all included patients had their health data taken at the 1-year mark since the first infection irrespective of the number of infections.

This study was a cross-sectional study where each group was compared to one another at the determined endpoint occurring after 1 year. The assumptions is that people from each group would be matched demographically so that the age and some health factors would be similar. Some additional weighting is also done to balance any discrepancies.

Now, this isn’t an issue as many studies are designed in this manner. However, this design may run into the issue of swapping cause and effect relationships, such that the phenomenon may be observed as being caused by one thing (in this case the increased risk of PASC and death due to repeat infection) when in reality it may be the effect that is leading to the results.

In essence, it may not be that repeat infections increase the risk of death or PASC, but that those who are in a more vulnerable state of health are likely to be at increased risk of reinfection and severe illness.

As always, such statements would require some evidence, and the researchers actually provide some demographic data which may allude to this fact.

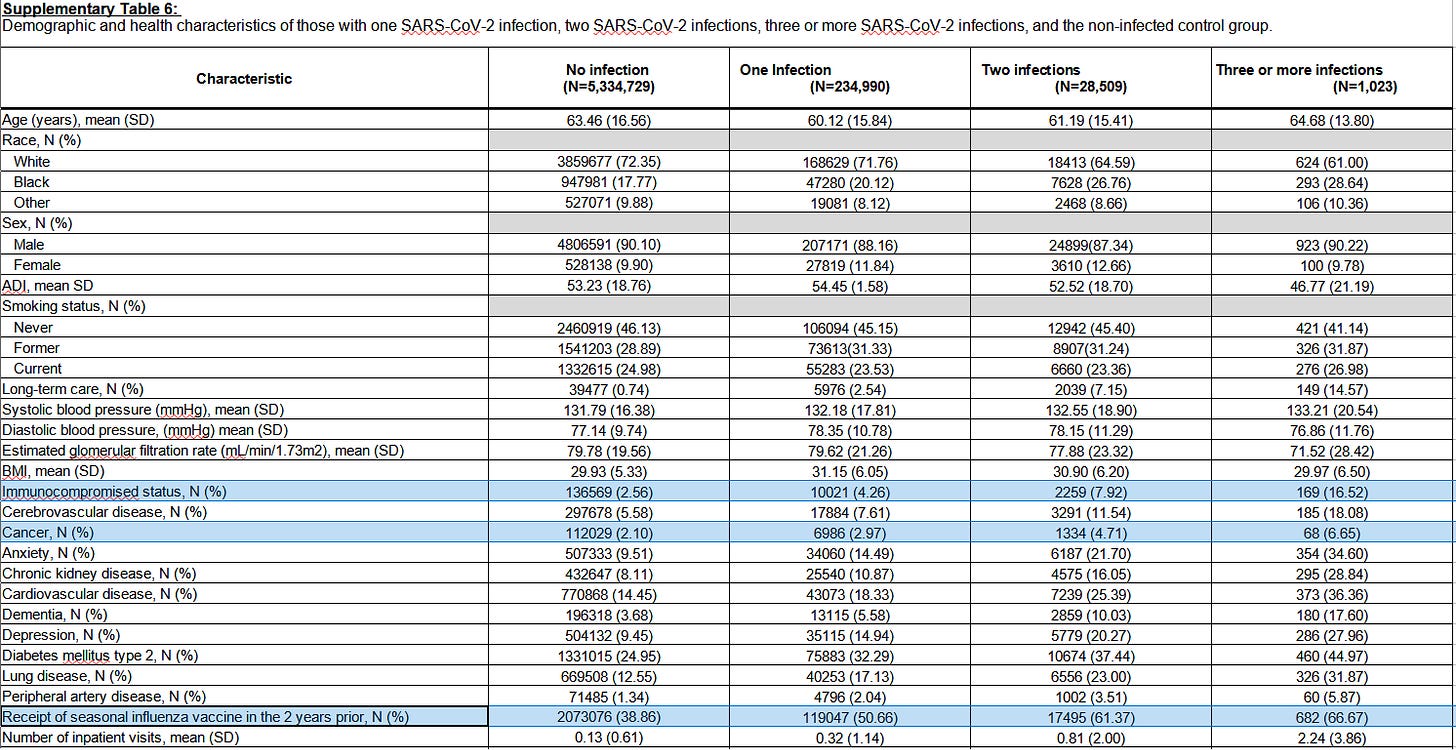

Supplementary Table 6 showed health information for patients in each category of infection including those who were never infected.

Now, when looking at the data there we need to be careful in looking at things that may be categorized as a PASC since that wouldn’t help in describing the wrong cause/effect relationship here.

However, there was a category which caught my eye.

The researchers included flu vaccine rates in the 2 years prior, meaning at a time before COVID.

Similar to other vaccines the flu vaccine is marketed towards those who are more vulnerable, including those who are older or have higher several comorbidities as can be seen on the CDC website below:

Note that we are making a large inference here, but with this information we may actually infer a correlation between flu vaccine rates and vulnerability, in that more vulnerable groups may have higher flue vaccine rates.

Interestingly, the researchers own data show that, with the snipped together information below:

As you can see, the percentage of flu vaccine recipients increased with the number of COVID infections. But remember that these numbers were taken before COVID, and so they almost act as independent variables since they should not be influenced by the current pandemic.

Once again, the numbers here may allude to the fact that those who were reinfected (at least within this cohort) were those who were already more vulnerable due to previously established health risks.

When looking at the broader demographic data this association can be seen in other variables as well, including the fact that those in the reinfection groups had higher levels of cancer and were more immunocompromised (apologies for the small font):

Both of these variables wouldn’t be accounted for in PASC, and for the most part shouldn’t be affected by repeat infections.

And so there appears that there could be a likely mix-up occurring here. Rather than repeat infections leading to increased risk, it may be likely that those who are more vulnerable and have several comorbidities are going to be more susceptible to reinfection, PASC, and possibly death.

In the comments section of yesterday’s post Brian Mowrey (seriously, have you subscribed to him yet?!) noted that a lot of the VA data appear to show higher rates of PASC than the normal population. Several researchers/doctors have also made note of that fact in comments on this study, such as this excerpt from Reuter’s piece:

Patients at VA health facilities are generally older, sicker people and often men, a group that would typically have more than normal health complications, said John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

This is again an issue where data is being extrapolated to make inferences to a wider population. The data here is heavily biased, and tends to skew rates of PASC, death, and hospitalization much higher than would be expected for the general population.

So does this study suggest more COVID = more death? I would argue no as it’s just as viable a claim to argue that those with more comorbidities may be at increased risk of multiple infections and PASC. But it is important to remember that this is just my perspective.

Nonetheless, it’s no surprise that this study is coming out at a time where there are renewed debates about bringing back mask mandates and that various attempts to halt vaccine mandates are being struck down.

Be careful for falling for more fear porn if it encourages the powers that be to bring back their draconian measures.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

One variable--maybe the most important variable--that I don't see mentioned in these studies is whether the subjects had received the covid experimental injections, and if so, how many. Are repeated infections occurring in people who have not had any of the injections? If so, how does the rate of repeat infections compare to the rate of repeat infection in the injected group? And are the long term consequences of repeat infections the same in both groups?

My 2 cents: I utilize the VA for healthcare and have taught classes there. There is no other single, unhealthy population (okay, maybe you can find one). Cigarettes, diet, morbid obesity, dependence on meds (many meds handed out like candy; except pain meds) rather than self care, type 2 diabetes runs rampant. If you want to study an unhealthy population you have it. I am in a small group: I am female, older, no shots: flu or covid. I am quite healthy and go out of my way to stay away from the VA.