Is Berberine really #nature'sOzempic?

With the growing popularity of Ozempic-like drugs natural alternatives have fallen into the eye of mainstream criticisms. How much of these concerns are genuine or lacking context?

As media buzz surrounding Ozempic and similar drugs have gained traction over the past few months, so too have other alternatives, which were touted as being cheaper and more readily accessible, especially given the fact that Ozempic-like drugs were not able to meet the public’s growing demands.

Now, I don’t use TikTok, but it’s been reported by mainstream outlets that several social media users, including some “influencers”, have taken to suggesting similar benefits to Ozempic-like drugs in a supplement called Berberine.

This has apparently spawned the hashtag #nature’sOzempic due to social media users likening the compound to Ozempic and other GLP-1 RA drugs, which has led to several million views online in association to this hashtag, including this one video in which a woman touts multiple benefits after a month of being on Berberine (although this video doesn’t appear to use this hashtag itself).

I won’t make any comment over the veracity of this video. Always keep in mind that a good deal of skepticism is required for any claims, especially ones that come from social media and may not be readily verified.

Unfortunately, due to this growing online interest of Berberine many mainstream outlets have seemed to have come out in staunch criticism of #Nature’sOzempic.

As the hashtag implies, scrutiny has been raised towards those who have touted Berberine as being synonymous to these highly popular anti-diabetes turned weight-loss class of drugs, with Berberine carrying the distinction of originating from nature and possibly giving it a sense of being safer and better.

Because of all this hubbub around Berberine I became curious and wanted to see what the truth was, given that many mainstream outlets tend to provide only partial truths.

Although originally intended to be a dive into Berberine in particular, I found myself going down a rabbit hole and looking at various news articles to see how they describe Berberine and see what narrative spin, or what partial truths they provide in their reporting.

So here, we’ll do a so-called “fact-checking the fact checkers”. Ok, maybe not a “fact-check” itself, but a review with the intent of laying out why the media isn’t very good at doing the one thing they are argued to do to do- report on facts and evidence.

Berberine Background

Although a deeper dive into Berberine will be saved for a separate post, it is still worth getting into some of the backgrounds of this supplement.

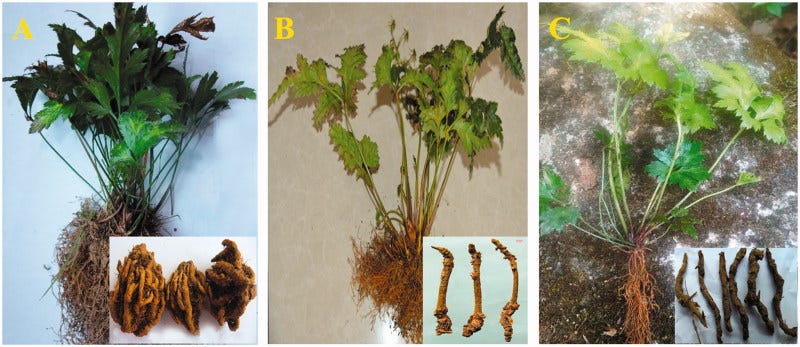

Berberine is a compound, in particular a quaternary ammonium, polycyclic alkaloid, found in several plants including goldenseal, Oregon grape, and most commonly Coptis chinensis, or Chinese goldthread, in which the rhizomes (roots) have been sourced and used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for hundreds of years.

Coptidis rhizoma has been noted several times in Chinese literature, being used for various ailments including gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses (Wang, et al. 20191):

The medicinal value of CR is worth affirming. Relevant statistics show that in 13 prescriptions before the Song Dynasty, more than 32,000 Chinese Medical formulae mentioned CR. Currently, CR is commonly used as a main traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to treat respiratory diseases (including tuberculous empyema, whooping cough, and pulmonary candidiasis caused by pneumonia), digestive diseases (including diarrhoea, chronic colitis and upper gastrointestinal infection), paediatric diseases (including hyperthermia of infantile external sensation, dyspepsia and urticaria), dermatological diseases (including acne, psoriasis, dermatitis and tinea pedis), and nervous system diseases (Wu et al. 2015). CR has been employed in the form of powders, pills or decoctions (Table 2).

Most reports suggest that this plant was used in the treatment of diarrhea, which appears to have carried over to modern use into treatment of bacterial diarrhea.

Although many of these traditional herbs contain various alkaloids, Berberine has become a compound of growing interest within recent years, mostly due to its possible antidiabetic, antilipidemic, antimicrobial, and in particular anticancer properties. It appears that the anticancer properties have been one of the main focuses of research when it comes to this compound, with searches and publications in recent years spiking due to this possible therapeutic effect.

Again, deeper assessments into Berberine will be saved for another post.

#Nature’sOzempic

One of the reasons I became curious of Berberine was because of media reports using the phrase “nature’s Ozempic”. This seems to have been a phrase that became widely adopted by social media users, much to the chagrin of mainstream outlets who find the need to fact-check everything for the sake of saving us from ourselves. I believe this was one of the reasons I came to know about Berberine in the first place.

Because of the popularity of this phrase it would be rather obvious of outlets to take advantage of social media algorithms and include this phrase within their headlines, and hence why I became interested in these supposed rebuttals to social media claims.

Here’s a few of the articles I came across, and ones I will reference in this article. I suggest people read these articles and see where overlaps lie in narratives.

My assumption with many of these outlets is that they are essentially following one another in a “blind leading the blind” sort of manner, in which the same points are hit across different articles even if there may not be merit in these arguments, mostly because they saw these points made in another writer’s article.

Also, note that several of these articles refer to “experts”. We should know by now that the reference to experts is nothing but meaningless given the fact that anyone can be made out to be a so-called “expert” these days.

Women’s Health Magazine: Is Berberine Really 'Nature’s Ozempic'? Experts Weigh In On The Viral Supplement

Rolling Stone: ‘Nature’s Ozempic’ Has a Pretty Gross Side Effect

Healthline: 'Nature's Ozempic': Can Berberine Really Help You Lose Weight?

Time: Why the Supplement Berberine Is Not 'Nature's Ozempic'

Scripps News: The back and forth on Berberine, the alleged 'Nature's Ozempic'

Teen Vogue: Berberine Isn't “Nature's Ozempic." Instead, Experts Warn It's Just Another Diet Culture Trap

Very Well Health: Berberine Isn't 'Nature's Ozempic.' But It May Help Manage These Conditions

NBC News: What is berberine, the supplement dubbed 'nature's Ozempic' on social media?

Huff Post: A TikTok Trend Claims This Supplement Is 'Nature's Ozempic.' It's Not.

CNN: Forget TikTok claims: ‘Nature’s Ozempic’ is no such thing, experts say

yahoo!style: TikTok Debunked: Is berberine really 'nature’s Ozempic'? Experts weigh in

Wired: TikTok’s Berberine Fad Is About More Than ‘Nature’s Ozempic’

The Guardian: TikTok users are calling berberine ‘nature’s Ozempic’ – but is it a fad?

Points of Contention

Like I said, many of these articles hit the same beats, aside from Teen Vogue which goes into a tangent on diet culture and the resurgence of “thinness” on social media. Strange, considering that obesity should never have been “in” when it comes to health and disease.

The Wired article also likes to go down a political tangent and argue that wellness gurus are leaning more to the right, with many people who turn to supplements and away from pharmaceuticals supposedly being more conspiratorial and right-wing in nature. Wonderful, since this likely draws upon political affiliation in argument rather than, you know, the facts and evidence we would expect from outlets…

Some more broad comments made include the following:

Berberine is cheaper than Ozempic and similar drugs.

This is a given fact. It doesn’t mean that Berberine is more effective or safer than Ozempic, but that Berberine is generally far less costly. There’s no arguing against this.

Berberine and Ozempic have different mechanisms of action, and so they aren’t comparable.

This argument seems to be done almost as a technical win for these journalists. It’s true that Berberine and Ozempic have different MOAs, but the comparisons being made between these two compounds is based on the effects they have on the body, in that they may help people lose weight, manage their glucose, and provide other benefits. Most people are not likely to know the concept of “mechanisms of action”, and to be quite honest I doubt most mainstream outlets are as well, so this is an argument that doesn’t seem to be more than an argument on technicality. As an aside, this reference to MOAs, strangely, seems to be something that has popped up more frequently in news articles as most articles tend to focus on telling readers what a drug treats rather than how it works.2

Consider that Metformin, a compound naturally derived from plants, requires a prescription. When seeing arguments about Berberine juxtapose those arguments with Metformin.

Berberine is “nature’s antibiotic”, and so use of Berberine will lead to antibiotic resistance and alterations in the gut microbiome.

This would be something concerning, if not for the fact that this argument can be somewhat meaningless in the grand scheme of things.

Berberine comes with a side effect of diarrhea, constipation and bloating.

This follows from #3. Ask yourself why exactly something that has an effect on gut bacteria may have such side effects as these…

Berberine is not regulated, most studies have relied on rodent models, and no studies have noted clinically meaningful use of Berberine for diabetes and weight loss.

There’s a lot going on here, and I haven’t looked through all of the clinical assessments myself. Instead, consider a model of consistency when seeing these remarks.

I think there’s a few more generalities that can be found across these articles, but I pointed these out in particular as things that I find to be rather interesting as criticisms as they are things that can either be refuted or verified through sourcing the literature.

Readers can find other points of contention, and in the list above #1 won’t be explored due to its self-explanatory nature.

Point #2: Different MOAs

Many outlets seem to have gotten caught up in this phrase “nature’s Ozempic”, and in doing so seem to find it necessary to make a technical argument in suggesting that these compounds have different mechanisms of action.

Consider this paragraph from Time’s article in mentioning this difference in MOAs:

The only problem is that there’s really no such thing as “nature’s Ozempic,” because Ozempic is far from natural. Semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic, Wegovy, and other prescription drugs, works in the body by imitating a hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1, or GLP-1, which is produced in the gut after eating and prompts the production of insulin. This makes semaglutide a great treatment for Type 2 diabetes and a promising one for weight loss, since it also mimics the feeling of fullness. But berberine just doesn’t work the same way.

The first sentence appears to confuse what the phrase “nature’s Ozempic” means. This phrase doesn’t suggest that Ozempic is natural, but that Berberine, in juxtaposition to Ozempic and Ozempic-like drugs, is natural. One can just use the phrase in a sentence such as, “Unlike Ozempic, Berberine is found naturally in plants and seems to have similar effects as Ozempic.”

But who am I of all people to criticize someone else’s writing? 🤷♂️

The article doesn’t go on to state what Berberine’s MOA is, just that it’s different than Ozempic, and therefore not comparable. This appears to be the case for several articles, in which Ozempic’s MOA is described but Berberine’s is made to remain ambiguous with only references it to it not being nature’s Ozempic, such as this quote from the Teen Vogue article:

“[Calling berberine nature’s ozempic is] suggesting that this item has the same qualities the other product has, or has some other similarity,” Mehal said. “There really aren’t any similarities.”

Again, no actual comparisons of MOAs…

One of the only articles that seems to suggest an MOA for Berberine is the one from Very Well Health:

Instead, berberine activates an enzyme called AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which can help regulate glucose metabolism, improve insulin sensitivity, and impact blood sugar levels.2

The HuffPost article goes a bit more technical in stating an association with mitochondrial function based upon a quote from Dr. Anant Vinjamoori:

“Berberine operates on the molecular level by subtly hindering the efficiency of mitochondria, which are the powerhouses of your cells,” Vinjamoori said. “In response, your body activates a pathway, which not only boosts insulin sensitivity but also promotes the production of more mitochondria. This approach might be likened to jogging with weights on, making the body work harder and thus ramping up its metabolic capacity.”

These two proposed MOAs may seem different at first, but there’s an association between AMPK and mitochondrial function.3

More importantly, this MOA seems to be similar to the antidiabetic, FDA-approved-but-originally-from-nature compound Metformin, which also has effects on AMP.

For instance, an article from Wang, et al. 20184 notes the following (emphases mine):

Metformin suppresses hepatic glucose production and stimulates glucose uptake in muscle and adipose, resulting in improvement of hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia and alleviating non-alcoholic fat liver disease (NAFLD) [17–19]. In addition to enhancing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, metformin can protect β-islets against lipotoxicity and glucotoxicity to restore insulin secretion [20, 21]. The first target of metformin identified is the 5′-AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK), although some effects are reported to be mediated through AMPK-independent mechanisms [22–24].

[…] Studies have indicated that, similarly to metformin, berberine executes its functions by regulating a variety of effectors including AMPK, MAPK, PKC, PPARα, PPARγ [28, 30]. To be noteworthy, via activation of AMPK, berberine can stimulate glucose uptake in muscle, liver and adipose, and inhibit gluconeogenesis in liver by downregulation of gluconeogenic enzymes (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxyl kinase and glucose-6-phosphatase) [31].

Note that these remarks shouldn’t be taken as 1-1 comparisons. However, what this suggests is that a lot of these remarks of different MOAs between Berberine and Ozempic are somewhat smoke and mirrors.

In essence, if Berberine has a similar MOA as Metformin, and Metformin appears to be given the gold seal of approval, then it sort of undermines the need to go down this route of technicalities to argue against one compound in favor of another. That is, if Berberine is questioned for its MOA then that likely puts Metformin in the same position. But instead, Metformin is seen as being acceptable due to being FDA approved and provided via prescription.

In many of these articles this comparison between Berberine and Metformin’s MOAs aren’t made aside from comments on FDA approval, and so it makes one wonder if information was omitted to provide a different framing of Berberine where a comparison is made to Ozempic in order to argue that they aren’t quite the same, while also omitting the possibility that Berberine is similar to Metformin, in which case the whole argument supporting Metformin but not Berberine falls apart.

It shows an inconsistency in argument, in which Berberine’s MOA is left ambiguous, likely due to overlaps with Metformin’s MOA, which makes criticisms of Berberine a bit more difficult without seeming hypocritical (my opinion, at least).

Again, at the end of the day, this seems like a technical argument that really has no relevance in the grand scheme of things, but just seems to be a deceptive framing device.

Point #3: “Nature’s Antibiotic”

In a weird attempt at framing Berberine as bad, several articles have used the phrase “nature’s antibiotic” when referring to Berberine’s possible antibacterial properties.

In Wired’s article they reference a Dr. Cassandra Quave who seems to make this allusion, as noted in the following quotes:

“Berberine is a natural antibiotic, so it interferes with the growth of different bacteria in the intestines,” she says. “This is not something you’re supposed to take on on a long-term basis, because you are changing the dynamics of your gut microflora.” Plus, berberine is known to interfere with enzymes in the body that break down other drugs, so it can cause dangerous interactions.

Berberine has antibiotic properties, as Quave noted, which is why it is often used to treat bacterial diarrhea on a short-term basis.

So I suppose framing only goes in one direction of acceptability…

I thought this phrase came up in other articles, and the name Quave sounded familiar. Apparently Scripp’s article also contains a quote from Quave as well where she makes the same remarks:

"Think of it as a natural antibiotic, and it works primarily in your intestines because the nature of the molecule doesn't really allow it to get out into your bloodstream very well. So it's used on a short-term basis to treat bacterial diarrhea. However, it does modulate your gut microbiome," said Cassandra Quave, Curator of the Herbarium and Associate Professor of Dermatology and Human Health at Emory University.

[…]

"We're starting to understand more and more about the gut microbiome. And there are certain things we shouldn't mess with, just as I wouldn't tell you, 'Hey, take penicillin just a little bit every day for weight loss.' No, it's not a good idea. And there's actually no real evidence showing that this helps with weight loss when it comes to scientific evidence," Quave said.

All of this sounds a bit scary upon first read. It is true that growing recognition of the microbiome comes with the fact that things are possible antibacterials would be rather concerning.

But once again, this problem requires additional context, in which case additional context makes this argument over antibacterial properties and fear mongering in regards to the gut microbiome a bit meaningless in nature, given that other compounds are suggested to show antibacterial properties, such as compounds in green tea5, honey6, and even capsaicin7- the spicy compound found in chilies.

So this argument can either relate to many different compounds found in nature, or maybe there’s something unique to Berberine and how it affects gut bacteria.

Here, it does appear that Berberine may influence the gut microbiome in some capacity, albeit in a rather nuanced and complex fashion. This may explain why pathogenic bacteria, which may cause gut distress and diarrhea, may be targeted by this compound, as noted in this excerpt from He, et. al.8:

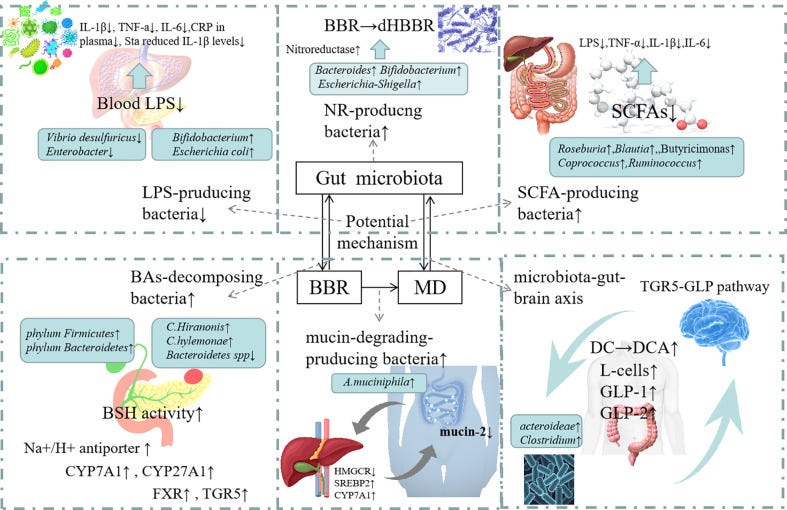

One of the most important functions of BBR is that it can change the composition of intestinal microbiota. A significant decrease in the total bacterial population was observed in rats treated with BBR. BBR has a broad antibacterial spectrum including opportunistic pathogens (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Salmonella, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas), inducing death of harmful intestinal microbiota (Escherichia coli), enhancing the composition of beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium adolescence, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and A.muciniphila) ( 85–89), and increasing the ratio of Phaeophyta to Bacteroides, etc. (90). All of these bacteria have a profound effect on blood glucose and lipids levels (91).

These comments are also mimicked in a review article from Wang, et al. 20229. Keep in mind that the references between the two reviews are likely to be similar/the same:

Berberine can induce cell death of harmful intestinal bacteria and increase the number and species of beneficial bacteria (Habtemariam, 2020). From administration to absorption, BBR can be metabolized by gut microbiota to improve its therapeutic effects on metabolism related diseases such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or directly affect gut microbiota to regulate and ameliorate metabolic disorders (Cui et al., 2018). The gut microbiota cuts down BBR to the absorbable form of DhBBR, which converts to BBR and enters the blood after absorption in intestinal tissue, so as to improve the bioavailability of BBR (Feng et al., 2015). Studies have shown that BBR can increase its oral availability and relieve metabolic disorder by reversing the changes in the quantity, structure and composition of gut microbiota under the pathological conditions (Table 1). At the same time, BBR improves intestinal barrier function and reduces the inflammation of metabolism related diseases by regulating gut microbiota. In addition, BBR achieves energy balance by regulating gut microbiota dependent metabolites (such as LPS, SCFAs, BAs) and related downstream pathways. What’s more, it can improve gastrointestinal hormones and metabolic disorders by regulating bacterial-brain-gut axis (Figure 2).

Some of these reviews seem to go against Quave’s remarks, including the possibility that Berberine can be metabolized and readily absorbed into the body.

All this to say that Berberine may just target bad bacteria while helping good bacteria, which is more complex than just an all-around antibiotic that may damage our gut.

There’s a clear recognition that the gut microbiome can influence our overall health. There’s also a clear recognition that what we put into our bodies, either by way of excess sugars and fats, may influence our gut microbiome as well. The two are heavily influenced by other another, and this balance may be disrupted by poor eating habits or other circumstances, as seen in obese and diabetes patients.

Thus, it’s important to keep in mind that many of these people who are seeking out Berberine, Ozempic, or things of this nature may already be dealing with gut dysbiosis of some sort.

And so, it’s quite possible that Berberine may aid in managing gut dysbiosis by regulating lipids and sugars, which may regulate gut bacteria10 by promoting good, beneficial bacteria. It appears that Berberine may increase the prevalence of short-chain fatty acid producing bacteria, which are suggested to be key players in our health as well.

In short, the comment that Berberine is “nature’s antibiotic” may be rather misguided, and likely overlooks the more nuanced role of Berberine in gut microbiome homeostasis. It doesn’t appear that Berberine is purely an antibacterial, but rather a modulator of certain bacteria, which may already be dysregulated in obese and diabetic individuals due to poor eating habits.11

Consider that many of these natural compounds are being looked at as possible alternatives due to antibiotic resistance, and so to claim that these are similar to antibiotics falls into the same fallacy as those who criticize the phrase “nature’s Ozempic”.

A bit ironic to be honest.

All of this feeds into the next point of contention….

Point #4: Berberine-related diarrhea

I’ve seen several comments online of people who had bloats, stomach cramps, and other GI issues when using Berberine, so this isn’t quite out of the ordinary.

However, outlets have taken to issuing this concern over diarrhea as a reason to not take Berberine, even though the stomach paresis that is being recognized by Ozempic-like drugs should raise serious concerns itself but may not appear to get the same level of recognition.

Rolling Stone is a prime example of this concern over Berberine-related diarrhea:

Perhaps even more worryingly, in addition to appetite suppression and sugar regulation, one of the closest similarities Berberine shares with Ozempic is its potential side effects. Because the supplement directly targets the gastrointestinal tract, it can help you lose weight, but it can also, possibly make you poop your pants. Gastrointestinal distress like constipation or diarrhea, as well as nausea and migraines, are side effects of Ozempic that are commonly documented on social media and can also impact Berberine users.

But given what we have outlined in Point #3 the explanation for these side effects may lie in the gut.

There’s some ambiguities in these side effects, but I am somewhat reminded of the fact that people who don’t regularly eat beans may experience flatulence. They are magical fruits…are legumes fruits?

Anyways…

The more someone eats beans the less flatulence they seem to experience. This seems to be due to bean-loving gut bacteria, which may gain in prevalence with increased bean consumption, and can readily digest components of beans making you less gassy and bloated.

Berberine’s gut modulating properties may work in a similar manner, in which the altering of gut bacteria may influence digestion and how glucose and lipids are regulated, leading to these symptoms of gassiness and bloating (speculation on my part).

What’s rather ironic is that these GI side effects are seen with Ozempic-like drugs, which the media seems to conflate, and so it’s again ironic that they argue that these compounds have different MOAs while also similar side effects.

One study in mice, which the Time article references, suggested that the use of Berberine may lead to gut dysbiosis and therefore diarrhea, although the study used a dose of 200 mg/kg of Berberine which may be far higher than is typical of supplements.12

Again, the actual reasons for these side effects are unknown. However, if we infer that people who are taking Berberine are doing so with the intent of losing weight, their diet may not be in order, and so these symptoms may be an indication of dietary choices that may not be beneficial for the gut microbiome or one’s overall health.

There’s a lot to consider about these side effects, including the health status of these individuals as well as their dietary eating habits, all of which may increase the risk of these side effects.

The main issue with articles such as the Rolling Stone’s is that it doesn’t provide an explanation for why these side effects may be occurring. Instead, outlets that report on these side effects are doing so with the possible intent to scare people from trying these compounds.

*I won’t cover the last one. I think it will be interesting to see if people look at some issues with this argument.

Listening to the media…

In writing this I went down a bit of a rabbit hole that I didn’t intend to. I started off wanting to write about Berberine in particular but became interesting in the media’s outcries over this supplement.

The old saying tends to go that:

If you don’t watch the news you are uninformed. If you watch the news you are misinformed.

However, I don’t take this saying to be entirely true, as we can see here that even across various news outlets there still seems to be a lack of truly informing readers on the nature of Berberine.

Consider that several outlets don’t seem to clarify Berberine’s MOA, or even take into account what this antimicrobial effect of Berberine may be a result of.

I find that some of the most egregious examples are videos such as this one from The Today Show, which doesn’t tell anything of actual value:

Much of this seems to be a general problem, in which the media may obscure evidence on not report on things that provide better information to readers and viewers.

In a more cynical sense, this may be intentional to create a more hegemonic narrative, and one that may go against establishment norms. However, I’m also inclined to believe that this is part of how the rush to report, get ahead of the narrative approach that the media takes can also lead to reports that otherwise lack substance and anything meaningful.

I jokingly stated that this article would “fact-check the fact-checkers”, but that wasn’t the main point. Instead it’s to point out why readers should seek out additional information and context in order to form their own opinions. There’s always more to the story, and rather than rely on news outlets, Substack posts, or whatever you may find on social media it’s important to do your due diligence when it comes to your own health.

Keep in mind that this article isn’t intended to make any argument over whether people should take Berberine. With any supplement, do your own research, seek out additional information, and reach out to pertinent medical professionals.

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Wang, J., Wang, L., Lou, G. H., Zeng, H. R., Hu, J., Huang, Q. W., Peng, W., & Yang, X. B. (2019). Coptidis Rhizoma: a comprehensive review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Pharmaceutical biology, 57(1), 193–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2019.1577466

If I was narcissistic I would argue that I played a role in this mentioning of MOAs since that tends to be something I am interested in. In reality, my Substack is far too small to have any reach, but I do find it strange that this is something that seems to be popping up more frequently. Or maybe it’s my previous lack of reading news articles that is making me misinterpret my assumptions.

Wu, S., & Zou, M. H. (2020). AMPK, Mitochondrial Function, and Cardiovascular Disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(14), 4987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21144987

Wang, H., Zhu, C., Ying, Y., Luo, L., Huang, D., & Luo, Z. (2017). Metformin and berberine, two versatile drugs in treatment of common metabolic diseases. Oncotarget, 9(11), 10135–10146. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.20807

Zhao, T., Li, C., Wang, S., & Song, X. (2022). Green Tea (Camellia sinensis): A Review of Its Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(12), 3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123909

Mandal, M. D., & Mandal, S. (2011). Honey: its medicinal property and antibacterial activity. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 1(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60016-6

Füchtbauer, S., Mousavi, S., Bereswill, S., & Heimesaat, M. M. (2021). Antibacterial properties of capsaicin and its derivatives and their potential to fight antibiotic resistance - A literature survey. European journal of microbiology & immunology, 11(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1556/1886.2021.00003

He, Q., Dong, H., Guo, Y., Gong, M., Xia, Q., Lu, F., & Wang, D. (2022). Multi-target regulation of intestinal microbiota by berberine to improve type 2 diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in endocrinology, 13, 1074348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1074348

Wang, H., Zhang, H., Gao, Z., Zhang, Q., & Gu, C. (2022). The mechanism of berberine alleviating metabolic disorder based on gut microbiome. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 12, 854885. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.854885

The cause/effect can be reversed here, where Berberine may target bad bacteria allowing room for beneficial bacteria to colonize and modulate lipid and sugar processing in the body.

Capsaicin also appear to be considered as a possible microbiome regulator, and research seems to looking into this possibility.

Rosca, A. E., Iesanu, M. I., Zahiu, C. D. M., Voiculescu, S. E., Paslaru, A. C., & Zagrean, A. M. (2020). Capsaicin and Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(23), 5681. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25235681

Again, there’s more complexity than what is being reported.

If we argue that the typical American male is around 100 kg, a dose of 200 mg/kg is equivalent to around 20,000 mg of Berberine, which may not be achievable for most people and therefore may not be a proper assessment of Berberine. Keep in mind that marketing by supplement companies for Berberine seem to play some tricks in how they label their “berberine equivalence” values. The Berberine used in this mouse study appears to be more than 98% pure Berberine.

"If you don’t watch the news you are uninformed. If you watch the news you are misinformed." I love that quote!

One additional perspective: the media derives much, maybe most, of its advertising revenue from pHarma. Berberine is cheap, effective, much safer than the pHarma drugs, fewer side effects. With a knowledgeable herbalist, even more effective. Gee whiz! Send out the attack (reporter) dogs

Those magazines are full of pharma ads. Pretty sure the word came down to slam any cheap/generic alternative to Ozempic. Ivermectin, anyone?