Is a vegetarian diet more protective against COVID?

And the strange, growing trend of pushing for less meat consumption.

These days it seems as if the media has been ramping up pro-vegetarian and anti-meat rhetoric, usually under the guise that reducing meat consumption may be far better for the environment and far more sustainable, as well as being far more beneficial for our overall health.

And this narrative has been ramped up even further with Netflix’s new series examining the effects of vegan diets vs omnivore diets in twins:

It’s no spoiler that the documentary’s own trailer is pointing towards major benefits from going vegan, along with some commentary on the environmental imperative for eating less meat. After all, many points of funding for the documentary and the Stanford study1 in which the documentary is based on seem to have roots in vegan and environmentalist groups. The documentary itself seems to be produced by the Oceanic Preservation Society which includes the following statement on their website:

OPS inspires, empowers, and connects a global community using high-impact films and visual storytelling to expose the most critical issues facing our planet.

So a documentary series by the environmentalists for the environmentalists.

Now, I personally don’t have any issue with people’s own dietary preferences. However, there’s a difference between scientific evidence and propaganda masquerading as The Science, and it appears that the current discourse over diets leans more towards the latter rather than the former. I wouldn’t be surprised if many of my readers have heard of people proclaiming the need for us to eat less meat because of climate change instead of it being a personal preference.

I have considered covering the Stanford twin study, but several people have already taken to doing so and so it’s not as high of a priority.

However, in the past few days a new study published in the BMJ2 has pushed more in favor towards a plant-based diet, this time with a study looking at different diets and how they relate to COVID outcomes:

This study was an observational study conducted in Brazil, which collected demographic, health, and COVID-related information of participants:

In the prospective observational study in Brazil called the Pandora Project, 723 adult volunteers were initially recruited through social networks and the internet during the period from 18 March to 22 July 2022. Initially, adults participants received an online questionnaire about sociodemographics, lifestyle, past medical history, eating patterns and eating habits. They were divided into two groups, omnivorous and plant-based, according to their self-reported dietary pattern. Both were requested to contemplate a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

Given that the study is a prospective study any incident of COVID is likely to be any recorded incident during the study period, although the authors don’t provide any information regarding prior COVID infection among the participants, which may influence future COVID infection risks and severity. However, bear in mind that this may be a misinterpretation of the findings on my part.

Also, note that this study is examining a timeframe where the Omicron variant was widespread.

Participants were divided into omnivore or vegetarian groups based upon how they answered a questionnaire:

A basic food frequency questionnaire served as a tool for validation of the main self-reported dietetic pattern. The omnivorous were those who consumed any food of animal origin. The plant-based food pattern included flexitarian/semi-vegetarian (individuals who consumed meat at a frequency ≤3 times a week); lacto-ovo-vegetarians (individuals who consumed eggs and/or milk and dairy products, but without meat, fish or other shellfish); and strict vegetarians or vegans (people who do not consume any kind of animal food, such as egg, milk and dairy products, fish and red meat).

The division between the groups is a bit ambiguous here as it would appear that flexitarians should probably be lumped into the omnivore group, however this is a problem more related to researchers in not providing clear definitions for their groups.3

When it comes to COVID infections there also is a lot of ambiguity, as the authors don’t provide any explanation for how they know that the participants had COVID. The language appears to suggest some confirmatory assessment, but without any clear details, and given the self-reporting method of this study it’s important to point out this issue.

The pertinent portion can be seen below:

Participants were asked about the presence of previous diseases through a confirmed medical diagnosis, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, cancer, kidney disease and others (yes, no). We examined the factors related to exposure to COVID-19 (relationship between social isolation, contact with the disease and frequency of exposure) and vaccination received (yes, no). The severity of the disease considered guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 and Pan-American Health Organization and World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), resulting in three distributions: no diagnosis of COVID-19; mild and moderate/severe COVID-19.14 Individuals reported the number of days of duration of symptoms.

Now, does this study provide anything significant when it comes to diet differences and incidences of COVID?

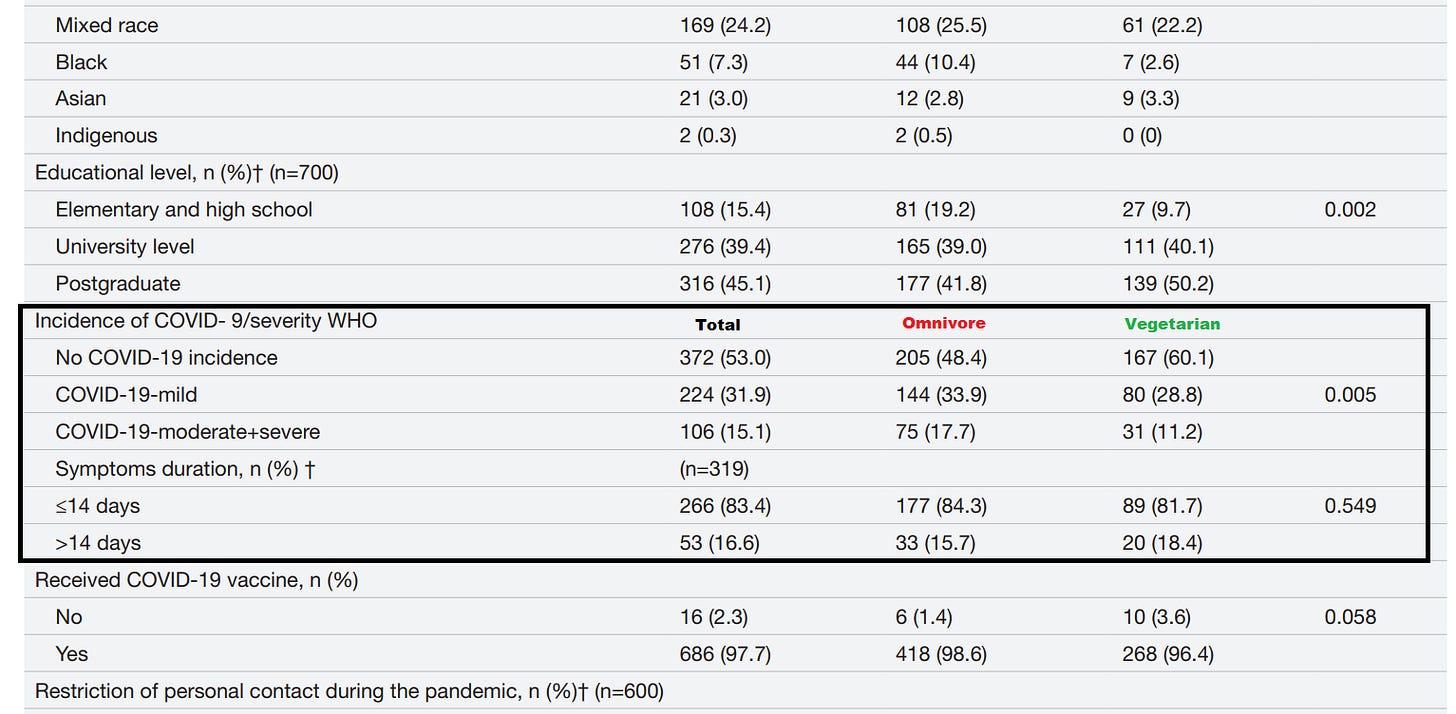

The findings would suggest that there were fewer incidences of COVID among the vegetarian group relative to the Omnivore group to the extent that reported incidences of mild and moderate-severe COVID were higher among omnivores:

Unfortunately, although the study attempts to control for confounders there are several issues with the study. For instance, note that the Omnivore group tended to have a statistically significant higher BMI, were less physically active, and had a higher proportion of participants who had comorbidities:

It’s known that poorer overall health may be reflective of higher risk of worse outcomes from COVID, and so it’s important to consider that these factors may be related to the incidences of COVID. Paired with the fact that the study was observational/self-reported there’s a lot of risk for biases and confounding factors.

Even worse is the fact that the researchers’ own remarks themselves mention a serious confounder, as vegetarians would obviously consume less meat than omnivores (they are vegetarians, aren’t they?).

Therefore, comments that, “a diet higher in fruits and vegetables and lower in dairy and meat may lead to lower incidences of COVID” doesn’t necessarily tell you if the lower incidences are related to higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, a reduction of animal-based products, or a complex mix of both.

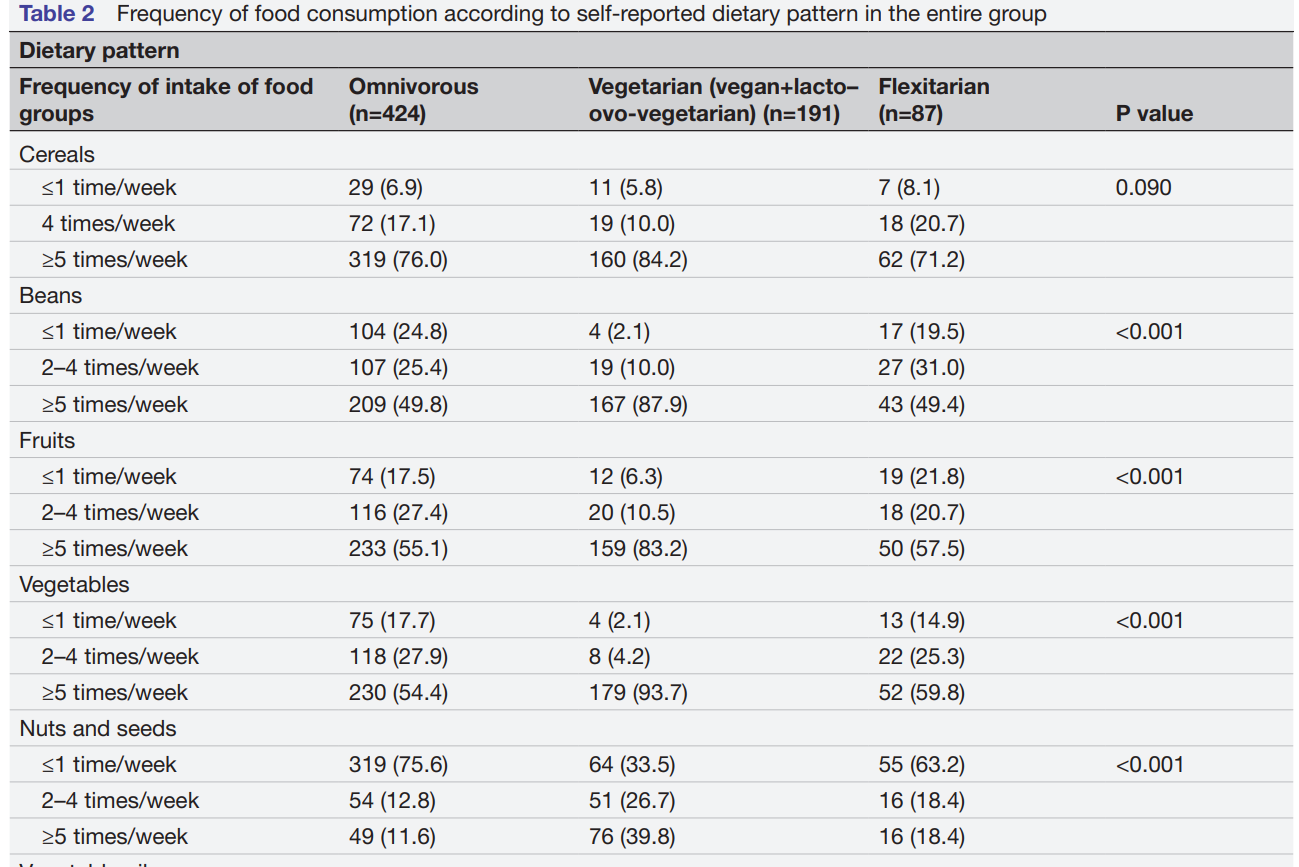

Note that, when compared to vegetarians, omnivores within this study consumed far fewer fruits, vegetables, and beans per week:

And so, hypothetically speaking, there may be some benefits associated with increased plant consumption alone, which may be difficult to measure when exclusion of meat is also taken into account. Keep in mind that a higher proportion of omnivores appear to consume at most 1 serving of beans, fruits, vegetables, and nuts a week relative to the vegetarian group.

In short, studies such as this one can’t really provide any clear line between diet and outcomes. The findings here are self-reported and heavily rely on participants being earnest with their reports. It also doesn’t tell us if the reason for these differences in incidences are due to benefits of plant diets, the harms of a meat diet, or a complex mix of both that isn’t properly captured in this study. The fact that the omnivore group appears to be overall less healthy relative to the vegetarian group is also a factor worth critiquing given the association between poorer health and worse outcomes related to COVID. This also includes an exploration into why the omnivore group had poorer health overall in this study.

This study also doesn’t provide any insight into the relationship between diet and risk of COVID infection/severity, and merely just points out that, based on the limitations of this study, that vegetarians appeared to have fewer incidences of COVID for some reason. Again, remember that this is an observational study and doesn’t provide insights into any causative explanation for these findings.

Overall, the issues with studies such as this one highlight some of the problems related to figuring out why certain diets may be beneficial and why some diets may be harmful.

The standard American diet (or SAD) is itself a multifaceted problem involving highly processed foods lacking nutrients and rich in fat, salt, and carbs. A diet simultaneously comprised of fried foods, prepackaged foods, preservatives, and processed meats while lacking any whole fruits and vegetables tells us that there is something seriously wrong with our relationship with food, and to tackle such a problem requires a complex approach in understanding what role each food plays in our overall health.

It’s a serious problem when we don’t take into consideration that diets are inherently inclusionary as well as exclusionary. So are vegetarians healthier because they eat less meat, or is it because they eat more whole fruits and vegetables? Could carnivore dieters fare well with a predominately meat diet if a person’s diet prior to starting carnivore is filled with chips and processed snacks?

It’s important to remember that nuance is key, and that you should consider multiple variables before drawing conclusions, especially if it means sweeping changes to one’s own lifestyle and habits.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Landry MJ, Ward CP, Cunanan KM, et al. Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2344457. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44457

Acosta-Navarro JC, Dias LF, de Gouveia LAG, et al

Vegetarian and plant-based diets associated with lower incidence of COVID-19

BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2024;e000629. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2023-000629

Note that flexitarian refers to individuals who eat predominately plant-based diets but will still occasionally consume meat. This definition still overlaps with omnivores, however the assumption may be that omnivores routinely consume meat. Either way, the flexitarian group was separated from the vegetarian group during the analysis and likely didn’t contribute to the overall findings.

Very good analysis. Another factor is that vegetarians and vegans are usually more careful about the quality of their food (not always), and consumption of corn byproducts and pesticide residues also play a role in overall health and susceptibility to disease. We would assume that the omnivores would be exposed to more of those “added” risks

I am a Vegan and I do not believe this study at all. I have had C19 and being Vegan didn’t prevent me from getting it. Likely, the Vegans were in general healthier than the Omnivore’s in the study. The SAD diet is just full of ultra processed foods sprayed with pesticides. Eat Whole Foods. Organic if you can afford it or pick the thing you eat the most of and buy organic of that item. The FDA has shown itself to be captured by big corporations for money, they are not looking for health problems from our food or pharmaceuticals. Buyer beware