In regards to a healthy microbiome

The problem with the Western diet and a broad overview of gut-related supplements.

Again, the following is not medical/nutritional advice, just something worth considering.

So far we’ve discussed the critical role of the gut microbiome in SARS-COV2 pathogenesis, as well as how many of the prior lockdown and masking policies may have worsened people’s microbial diversity.

Therefore, it makes sense to consider ways in which one can heal their or protect their gut.

We’ll take a look at a few broad ways in which one can help their microbiome, while noting one of the biggest issues with the modern Western diet in contributing to gut dysbiosis.

No Perfect Microbiome

As we discuss what makes up a good microbiome, we should remember that the microbiome itself is a rather nascent topic, only gaining prominence during the turn of the millennium. Even just a few years ago it was assumed that many of our organs, including the lungs, were sterile environments, and it’s clear that evidence in the field is limited for anything outside of the real of the gut microenvironment.

And that’s not even taking into account the slew of other factors that influence our microbiome, such as if someone was born via C-section1 or breastfed2, the ethnicity of an individual3, the person’s sex4, a person’s age5, and even the medications a person takes6, all of which would also be influenced by behavior and diet.

The list of variables influencing the microbiome may rival the microbiome itself (hyperbolic, but possible…maybe).

Because of all of these factors, and due to limited research, there is no good way to describe the perfect, ideal microbiome, as what may work for some may not work for others.

A lot of this variability may stem from genetics, as in the case of sex, age, and ethnic differences in microbiome, but all of these may also differ based on cultural factors such as differences in diets and lifestyles, which again may have gone through their own selective pressures over many years only to be abruptly changed with the advent of international travel.

So don’t fret over attempting to cultivate the most perfect of microbiomes.

Now, with that said, there is one critical factor that has been a detriment to our microbiome, owed to modernization and heavy processing, and that is the Western Diet.

Damage from the Western Diet

Irrespective of all of the nuances in variability from other factors, it’s quite clear that one of the biggest contributors to widespread dysbiosis is the adoption of the Western diet.

A diet heavy in ultra-processed foods devoid of beneficial nutrients and full of preservatives has led to increasing rates of obesity, irritable bowel disease, and other related maladies.

On one hand, the heavy manufacturing and processing of foods have made some nutrients more accessible. As noted by Zinöcker, M. K., & Lindseth, I. A.7 the processing of foods ruptures many of the cells of plants and animals, making these cellular components easier to access:

Throughout the human evolution, nutrients had to be released from cells (with a few exceptions, such as nutrients in milk, honey and eggs) to be available for uptake by the enterocytes. However, in a Western diet, a large share of the energy is provided by acellular nutrients; a term coined by Ian Spreadbury [38]. Acellular nutrients, i.e., nutrients not contained in cells, provide microbial and human cells with more easily digestible substrates [39] that influence human absorption kinetics [40,41,42] and are likely to influence intestinal bacterial growth [38].

A move towards acellular food components may not be all bad, as many of these components may not have been available for our ancestors due to the inability to digest certain plant material and lyse plant cells.

However, this processing also comes at a cost of various nutrients. Let’s consider whole grains, comprised of complex carbohydrates among other things. Milling and refining of grains will break down many of those complex carbohydrates into more simple, easier to digest compounds which will alter the microbiome as sugar-hungry bacteria may gain in numbers. So the balance in processing may alter the number of bioactive plant compounds and introduce a much higher level of easily digestible carbohydrates not seen in many of our ancestors.

This would be a negative effect of overnutrition, as the abundance of sugars and processed fats may provide far too many calories with limited nutritional value.

Take into account that many packaged foods are also full of preservatives and the damage to the gut is multi-fold. Compounds such as sodium benzoate and other preservatives are added to foods to extend their shelf life by inhibiting microbial growth. Of course, if such compounds are intended to inhibit bacterial growth, this should also have a detrimental effects on our own microbes.

It’s worth noting that some preservatives such sodium benzoate are found naturally in plants and most likely play similar roles there as well. However, once again all of this is a balancing act. The issue with modern diets is that preservatives are introduced in many pre-packaged foods, and it’s very likely that a person may consume several sources of preservatives throughout the day. Several of these items are also likely to contain several preservatives rather than just one, an effect referred to by Rinninella, et al.8 as a "cocktail effect" as there may be an overlooked synergistic effect in the consumption of so many preservatives.

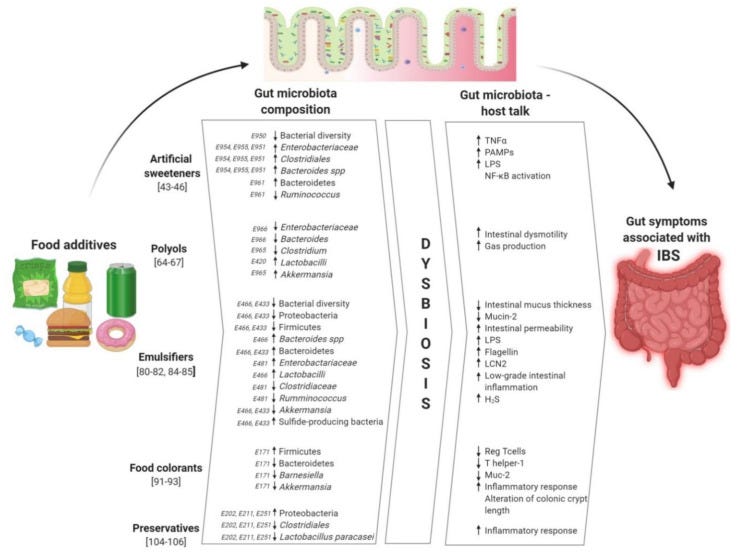

Many processed foods may also contain various emulsifiers, sugar substitutes, artificial dyes, and other agents that aren’t conducive to good gut health, as summarized in the following figure:

Although the Western diet may be inundated by overly processed, preservative-laden foods the answer to remedying this issue is rather straightforward.

I’ll leave Zinöcker, M. K., & Lindseth, I. A. to provide the rather obvious answer here (emphasis mine):

We argue that, first of all, we need to fix the food. We need to provide a better and more updated answer to the question: What should we eat? The question appears to have a rather simple answer provided by our evolutionary history: Eat mostly whole foods. This approach corresponds with findings from a wide range of nutritional studies where whole foods are consistently associated with good health.

Now, usually the provided solution may be met with immediate alterations in diet. As January is the month of resolutions and lifestyle changes, one may consider tossing out all bad foods and replace them with organic, locally grown foods instead.

Although ideal, this is also a tall order for many people to suddenly change eating habits which may not be sustainable, may become costly, and may actually be met with some discomfort as the introduction of whole, plant-based foods may cause indigestion and bloating as the microbiome alters to accommodate this new diet—the gut responds rather quickly to diet alterations. This may make it easy for people to give up healthy eating due to the negative feedback from the discomfort.

Instead, it’s worth viewing this process as in the same vein as many others, in which the process taken is slow and methodical. A slow decline in processed foods paired with more fruits, vegetables, and minimally processed meats may be more sustainable in the long run and will be more manageable for many.

Altogether, the Western diet has been one of the biggest contributors to modern gut dysbiosis with a rather easy solution.

It’s important to highlight the significance of the diet before getting into nuanced territory, as many of these other methods may be considered futile if the diet doesn’t change as well.

Remember, you can’t out-supplement a bad diet.

Supplementing the Gut

With that being said, let’s consider other options, mostly in the form of prebiotics and probiotics. Note we will be covering these ideas very broadly.

Several terms are thrown around in the microbiome literature including probiotic, prebiotic, synbiotic, and postbiotic. It all can get confusing, and there’s a ton of overlap between the groups.

Here’s a brief rundown of how these terms are defined:

Probiotic: The term continues to undergo alterations, but probiotics generally refer to living, beneficial organisms that one may ingest or apply to aid in overall health. Probiotics include supplementation with capsules containing different probiotic strains, or consumption of fermented foods such as yogurt, kimchi, or sauerkraut.

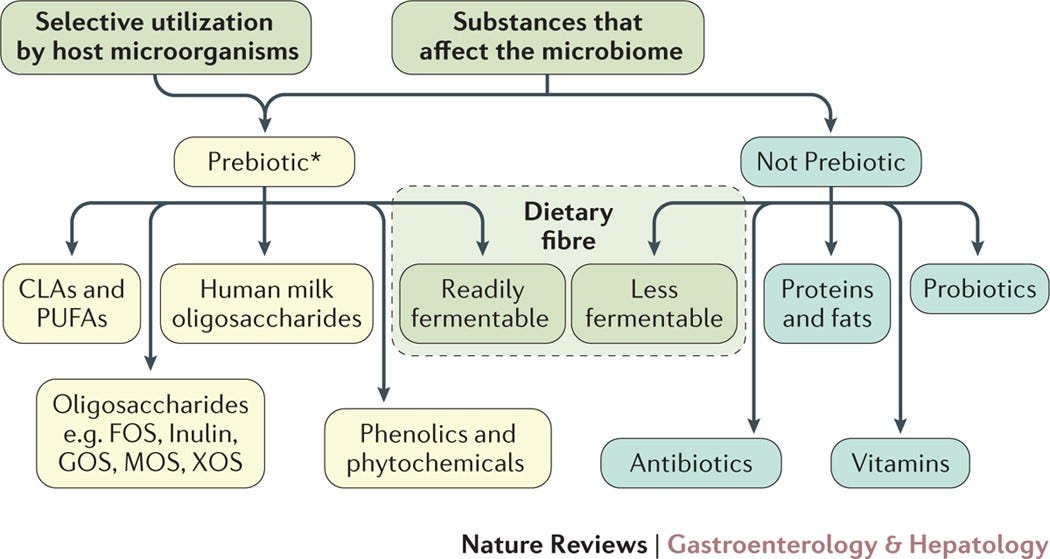

Prebiotic: Prebiotics can be considered food sources for probiotics or other commensal bacteria. They generally refer to non-viable compounds or substrates that serve as nutrients, which can include a select number of fatty acids and plant compounds such as oligosaccharides and dietary fiber. The term appears to be limited to compounds that selectively benefit commensal bacteria and not opportunistic or pathogenic ones. As such, compounds are not necessarily considered a prebiotic unless it biases towards beneficial, commensal bacteria.9 Vitamins and proteins aren't considered prebiotics as they may be metabolized by host enzymes. Again, the definition of a prebiotic continues to undergo revision and may likely have a different definition. The following chart breaks down what constitutes the current definition of prebiotic:

Synbiotics: Combinations of prebiotics and probiotics intended to improve human health. Synbiotics haven’t been explored in full relative to prebiotics and probiotics separately. Of course, it would also seem inherent to pair bacteria with necessary nutrients, so synbiotics as a concept may seem rather obvious. Some synbiotics may contain select bacteria such as Bifidobacterium or Lactobacillus paired with an oligosaccharide or fiber.10 It’s assumed that such a pairing would have an inherent synergistic effect, and development into more synbiotic formulations are being developed.

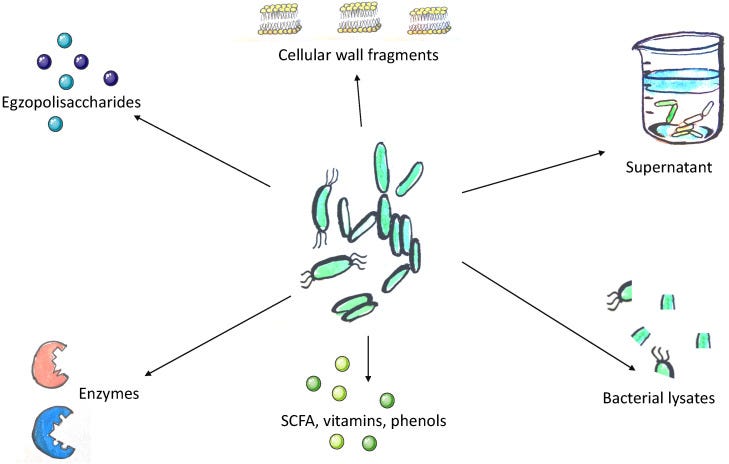

Postbiotics: Postbiotics are one of the newest and most ambiguous topics in the microbiome discussion. Postbiotics refer to metabolites and products released by bacteria. The clearest example would be vitamins and short-chain fatty acids produced by commensal bacteria that greatly benefit us. Many probiotics food products are likely to contain many postbiotic compounds within them, as they are likely produced during the fermentation process. Similar to synbiotics the concept of postbiotics may seem rather redundant, but growing interest may want to examine what specific postbiotics for therapeutic purposes as some postbiotics appear to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties.11

Research into the benefits of probiotics have suggested several benefits, but depend heavily on various factors and contexts.

Valdes, et al.12 examined several studies and noted a general benefit:

The analysis of 313 trials and 46 826 participants showed substantial evidence for beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation in preventing diarrhoea, necrotising enterocolitis, acute upper respiratory tract infections, pulmonary exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis, and eczema in children. Probiotics also seem to improve cardiometabolic parameters and reduced serum concentrationof C reactive protein in patients with type 2 diabetes. Importantly, the studies were not homogeneous and were not necessarily matched for type or dose of probiotic supplementation nor length of intervention, which limits precise recommendations. Emerging areas of probiotic treatment include using newer microbes and combinations, combining probiotics and prebiotics (synbiotics),91 and personalised approaches based on profiles of the candidate microbes in inflammation, cancer, lipid metabolism, or obesity.92

A review from Coman, V., & Vodnar, D. C.13 also compiled several of these studies and made the following remarks:

Recent meta-analyses of RCTs in adult populations have shown that probiotics could have beneficial effects in treatment and prevention of gastrointestinal diseases in general (74 RCTs) (Ritchie and Romanuk, 2012), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (43 RCTs) (Ford et al., 2014b), blood pressure (9 RCTs) (Khalesi et al., 2014), and depressive symptoms (10 RCTs) (Wallace and Milev, 2017). Pre- and probiotics have been also associated with a positive role in modulating immune responses to respiratory viruses, resulting, for example, in an increase in seroconversion and seroprotection rates in adults (and especially in healthy older adults) vaccinated against influenza (Lei et al., 2017). Based on such results, several authors have recently hypothesized that diet supplementation with pre- and probiotics may be beneficial in the current context of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (Sars-CoV-2) pandemic (Baud et al., 2020; Dhar and Mohanty, 2020; Infusino et al., 2020), especially for older adults, who are at a higher risk for developing more serious complications from COVID-19 illness (Bialek et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a).

It’s important to note that the results of studies are rather limited. Many studies rely on small sample sizes or animal models. There’s also the issue of which strains of bacteria studies use, as well as the issue in dosage, survivability, and colonization by these probiotics.

Interestingly, probiotics appear to provide benefits for those suffering ulcerative colitis (UC) but limited benefits in those suffering Crohn’s disease (CD), as noted in a review by Martyniak, et al.14 [context included]:

Research on the use of probiotics in IBD shows inconclusive results. There are indications that selected probiotics may be effective in inducing and maintaining remission, but this effect is more pronounced in UC patients than in CD patients. Among the available probiotics, VLS#3 [a “medical food” probiotic for IBS and UC] brings the greatest benefit from supplementation, although not all studies confirm this effect. The use of multi-strain probiotics appears to bring more benefits to patients than the administration of single-strain probiotics. Due to the large number of probiotics whose effects are assessed by clinical trials, it is difficult to compare the results between individual studies [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. More research is needed to assess the effects of individual probiotics in IBD patients.

Because of these conflicting results, it’s important to examine the intentional use of probiotics within the context of the disease it is intended to treat. Remember that probiotics may come with adverse consequences in those who suffer from serious gut permeability, and so its use may be rather detrimental. This appears to a proper concern in severely ill patients, and something worth considering in providing some hesitancy.

Also, the formulation of many probiotics should be examined. A critical issue with probiotics is in figuring out whether the bacteria take hold within the gut of the individual, as well as other factors that may influence this. Probiotics as a whole aren’t as tightly regulated as pharmaceuticals, so purity and authenticity of products should always be considered as well.

In short, probiotics appear to be beneficial, but stronger studies and greater scrutiny of available products should be warranted. Many other aspects of supplementation are not as clear, but it may be beneficial to consider select carbohydrates and fatty acid supplementations along with probiotics as a means of providing a synergistic effect.

In Consideration of the Gut

Plenty more can be covered with respect to helping the gut including the use of vitamins which appears to have mixed results depending on the vitamins used.

As many of the studies on the microbiome are difficult to compile due to heterogeneity and the disease looked at in question, a post trying to encompass everything would take weeks and dozens of pages.

For the lay person looking up specific probiotics, plant compounds that benefit the gut, different fermented food products, or even the preservatives in food can all become too overwhelming.

The intention of starting the post the way I did was to show that the finer details may not mean much in the grander scheme.

Here, consider the phrase K.I.S.S, or “keep it simple, stupid”.

Not that any of you are unintelligent, but rather than become confused in searching for THE ANSWER consider the little things that you can do to help improve your gut.

Consider starting off by incorporating more whole foods into your diet, as well as probiotics and prebiotics if one may find them necessary, although you may want to do your own research beforehand. Try a diverse array of foods, but don’t get bogged down in figuring out the perfect group of foods to eat.

Keep it simple and don’t overthink it.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Ríos-Covian, D., Langella, P., & Martín, R. (2021). From Short- to Long-Term Effects of C-Section Delivery on Microbiome Establishment and Host Health. Microorganisms, 9(10), 2122. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9102122

Gopalakrishna, K. P., & Hand, T. W. (2020). Influence of Maternal Milk on the Neonatal Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients, 12(3), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030823

Gupta, V. K., Paul, S., & Dutta, C. (2017). Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162

Vemuri, R., Sylvia, K. E., Klein, S. L., Forster, S. C., Plebanski, M., Eri, R., & Flanagan, K. L. (2019). The microgenderome revealed: sex differences in bidirectional interactions between the microbiota, hormones, immunity and disease susceptibility. Seminars in immunopathology, 41(2), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-018-0716-7

Salazar, N., Arboleya, S., Fernández-Navarro, T., de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C. G., Gonzalez, S., & Gueimonde, M. (2019). Age-Associated Changes in Gut Microbiota and Dietary Components Related with the Immune System in Adulthood and Old Age: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 11(8), 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081765

Weersma, R. K., Zhernakova, A., & Fu, J. (2020). Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut, 69(8), 1510–1519. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320204

Zinöcker, M. K., & Lindseth, I. A. (2018). The Western Diet-Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients, 10(3), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10030365

Rinninella, E., Cintoni, M., Raoul, P., Gasbarrini, A., & Mele, M. C. (2020). Food Additives, Gut Microbiota, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Hidden Track. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(23), 8816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238816

Gibson, G., Hutkins, R., Sanders, M. et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14, 491–502 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

The definition has gone through several revisions similar to probiotics, and at the time of the article’s publication the consensus definition appears to be the following (with additional context on this consensus included):

Given the proposed definitions already described, as well as others, the need for a consensus definition was evident23. This need was amplified by views that the prebiotic concept required clarification on specificity, mechanisms of effect, health attributes and relevance, with some authors being critical of concepts already put forward and its approaches24,25,26. Thus, the current ISAPP consensus panel now proposes the following definition of a prebiotic: a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit (Box 1). See Box 2 for additional rationale used to adopt this new definition.

The current (as at the time of publication) revision was intended to be broader and encapsulate more than just a select few bacteria, as bacteria from many different phylum may benefit from prebiotics. The use of the term “substrate” was intended to also be a broader term as well.

Markowiak, P., & Śliżewska, K. (2017). Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients, 9(9), 1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9091021

Żółkiewicz, J., Marzec, A., Ruszczyński, M., & Feleszko, W. (2020). Postbiotics-A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients, 12(8), 2189. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082189

Valdes, A. M., Walter, J., Segal, E., & Spector, T. D. (2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 361, k2179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179

Coman, V., & Vodnar, D. C. (2020). Gut microbiota and old age: Modulating factors and interventions for healthy longevity. Experimental gerontology, 141, 111095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2020.111095

Martyniak, A., Medyńska-Przęczek, A., Wędrychowicz, A., Skoczeń, S., & Tomasik, P. J. (2021). Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, Paraprobiotics and Postbiotic Compounds in IBD. Biomolecules, 11(12), 1903. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11121903

It helps to love at least a couple of fermented foods. Like, e.g., plain full fat yogurt and kombucha. The kombucha you can buy and then just a drink a bit every day. You don’t need the whole thing. Most cultures have some sort of fermented food. Yum.

this is a hot topic, thank you for writing about it! Its one ive dipped into personally. Functional Medicine focuses on the gut microbiome as a birthplace for health and disease (my language), they seem to have good reason for this perspective.

My own study/exploration into nutrition was driven by a need to cultivate a healthier gut + immune system, and has led me towards a primarily unprocessed or whole foods diet (a personal opinion is that 'plant base' may be misleading, because its tagged into foods which are highly processed, such as 'plant based meat' -my 2 cents)..... I appreciate the comments abt fermented foods.

Ive started to explore the question of WHY the body is impaired from functioning optimally... this led to inquiring if there are environment factors which impact the gut... I found Stephanie Seneff's book Toxic Legacy, a detailed review of her research on Glyphosate- its biochemical and pathophyiologic effect on living organisms... its an incredibly informative and damning report on big-Ag's affect on the quality of our food. She's a research scientist from MIT, Glyphosate is one of her focuses, aka roundup (a herbicide, dessicant but also an ANTIBIOTIC). She describes how it disturbs the balance of microbes in the human gut (plus a host of other deleterious mechanisms and proposed effects). I encourage anyone interested to listen to her lectures online (before diving into her dense book), shes very knowledgeable, informative and may shape decisions made around food shopping.

Modern, thanks for this post.