How I Tackle Reading Papers

A few informal notes on how I approach science papers and what to look out for.

Substack has been a great source for independent journalists and reporting that falls outside mainstream narratives, usually providing readers with differing perspectives and more nuanced discussions.

However, the idea of “rush to report” may still occur on Substack, leading people to quickly summarize a study rather than spend time breaking it apart and examining the finer details.

There’s been a growing concern of mine that many readers may spend more time commenting on studies rather than reading studies for themselves.

However, people also can’t be blamed- most people are busy with their daily lives and may not have time to sit down and parse the information in a study. It’s especially a serious issue if extensive background knowledge is required.

Therefore, rather than continue to report on studies I thought it would be better to outline how I try to tackle studies so that you can understand what’s important, what may not be worth reading, but more importantly how studies are written to be deceptive and rely on the fact that most people looking at a study are likely to not read it at all.

To Start Off…

First, let me be very clear— papers are very hard to read! And no, this isn’t me trying to blow smoke up my own rear end by saying that I do it better. In fact, I have much to learn in reading studies and am in no ways an expert!

Papers can be very difficult because they may require extensive knowledge on the topic or require an investigation into the lab techniques that were used in order to figure out how the study was conducted. Usually most people don’t have the proper knowledge and therefore a study may be read superficially based on the information that one may deem accessible.

For example, the recent ADE study that was widely reported on last week had researchers use a modified cell line called Clone 35. Do you know what Clone 35 is? That may require more reading leading to a prior article released by the researcher which then would itself require some perusing to get the relevant information.

What about the monoclonal antibodies cited including Sotrovimab, Casirivimab, and Imdevimab? That may require additional reading on relevant studies there as well!

It’s not uncommon to find out that you may have to spend more time going down rabbit holes in order to understand a study rather than spend time reading the actual study.

Some studies may take a day for me to read. Others, such as the immune imprinting study that was being implicated as an example of OAS took 2-3 days for me. When I generally say that I spend a good deal of time reading studies, I mean it!

Of course, I’m likely to be on the slower end of the reading scale and I tend to have an issue of knowing when to stop going down rabbit holes.

In short, don’t underestimate the challenge of reading a study. They are not designed for the layperson, and it’s a rather dangerous game to play if one were to read them from the perspective of a layperson rather than the perspective of a scientist.

More importantly, understand that when shown a study it is very likely that you will hardly be well-equipped to read the study on its own. In many cases additional reading would be necessary. Be careful in assuming that a study can be tackled without acquiring more knowledge beforehand.

There’s likely a few more things I’m missing but as we go through this article hopefully some of those ideas will be fleshed out.

Studies and how they’re organized

Most science articles are written following the same or similar organization:

Title

Abstract

Introduction

Materials & Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

Sometimes #4 may go after #7 and 6 & 7 may just be put together. You may also find supplemental material included at the end. Either way, this format will be what one typically comes across.

We’ll spend a brief bit of time highlighting each section and what some key features are of each.

1. Title

This is rather self-explanatory. A title just states what the study was about. Sometimes the title can be rather ambiguous which may usually happen with a literature review that gives some overview on a topic.

For instance, here is one review article about the immune system that uses a very simple title:

Overview of the Immune Response (Chaplin, D. D.1)

Sometimes a title may explain the setup for a study that will be further addressed in the body of the work, such as this one:

Comparison of Subgenomic and Total RNA in SARS-CoV-2 Challenged Rhesus Macaques (Dagatto, et. al.2)

And some may just be super wordy and just explains the findings directly in the title including the conclusion, such as this article:

Over expression of ACE in myeloid cells increases immune effectiveness and leads to a new way of considering inflammation in acute and chronic diseases. (Veiras, et. al.3)

Titles are the first thing one sees when provided a study, and unfortunately this reality creates a double-edged sword.

On one hand, this is a positive since most people would want to know if a study is worth their time. A quick glimpse at a title may provide them with enough information and context that tells someone it’s worth checking out the study.

On the other hand, most scientists and publisher’s are aware of how deep a layperson will go into a study. Sometimes this may lead researchers to use a bombastic title for their study even if the actual evidence is rather nuanced or may not be even substantiated.

Most publishers also know that there are a few pieces that someone will read before drawing conclusions on a study, with the title being one of those places.

Therefore, the title may be designed in a way that causes others to reference or cite a study and pontificate on the title alone without even reading the study. This is extremely dangerous since it may lead people to improperly draw conclusions from a study without even bother seeing what the study is about.

What importance do titles serve?

The title is always a good starting point to see if a study is worth reading. The title most likely won’t act alone, but be careful in taking the title as being the be-all, end-all of a study. Understand that hyperbolic, bombastic titles are likely the “new normal” for publications and don’t fall for thinking that such titles are a reflection of the actual evidence.

Check the title and then dig a little deeper.

2. Abstract Section

Following the title the abstract is where most people get the information for a study.

An abstract generally consists of a summary of every other section in the paper, sometimes in the form of one sentence. For example, an abstract may summarize the introduction in one sentence, methods in another, results in another, and so on until a paragraph is constructed that intends to provide a summary of the entire paper.

Abstracts are another way of figuring out if a study is worth reading since it provides more details that would otherwise not fit in the title. It’s a good way of getting a slightly deeper dive into what the study would cover.

But the abstract is, by all accounts, one of the most dangerous and most misleading parts of a study. Most people make it to the abstract and stop there, usually believing that the abstract provides an accurate retelling of the study.

Again, similar to the title the abstract can be full of inconsistencies or inaccurate summaries that may make readers fall into the trap of citing a study under the assumption the abstract is sound. Keep in mind that many articles hidden behind paywalls may only provide the title and abstract portions of a paper. People who may not want to pay or “sail the high seas” to find another way of accessing the paper may just take the abstract and use it as proof of the veracity of the study’s claims.

Remember that publishers and researchers count on the fact that the layperson won’t do a bit of digging.

In the broader context, this become a serious issue in which one person may cite a study only having read the abstract and pontificating on that portion alone. Then another person may cite that article under the assumption that the previous writer or researcher actually read the article. Continue this trend and it’s not uncommon to find several degrees of separation, all of which were based on false pretenses that assume to know the actual contents of a study— all because someone decided to read the abstract alone and report on that.

This is typically common among mainstream outlets, but it can occur with independent journalists as well. I have cited a few studies based on abstracts alone before I found “ways” of reading studies that may otherwise be behind a paywall…

It’s a common practice that, for all intents and purposes, is extremely damaging to the reporting of science.

Interestingly, if you were to type in “misleading abstract” you are likely to come across a ton of articles raising concerns about an “abstract-only” practice of reading papers.

There’s even this one article from Mathieu, et. al.4 in which researchers checked for misleading abstracts by comparing the abstract to findings in the results section of over 100 RCTs on rheumatology.

Although only a few studies were deemed to have a misleading abstract (about 1/4 of the included studies) the researchers commented that nearly all of the articles with misleading abstracts were studies that showed negative results.

This could be a consequence of publications only wanting to publish positive results, and by muddying the results in the abstract a researcher may be more likely to get published, although at the expense of having their work then be improperly cited and lead to misleading or inaccurate conclusions.

As a relevant example, a while back a study citing the effectiveness of Ivermectin and decreased mortality began widely circulating around Twitter and Substack. However, at the time when I tried accessing that study all I got was a title and an abstract-nothing else, and yet it was being touted as evidence that Ivermectin was effective against COVID. The article was eventually retracted (I believe this5 is the article in question although someone can correct me) with some comments about how the article was being misused.

Now, I won’t weigh in on the effectiveness of Ivermectin, but I found it rather concerning that an article was widely circulated as evidence of Ivermectin’s effectiveness on the premise of the abstract alone. Why tout the veracity of the study if there was no study to even examine?

It’s an example of taking an “abstract-only” approach only to end up being embroiled into another controversy that may have been avoided if some hesitancy was taken beforehand.

The importance of abstracts

Abstracts are a great place to see what the rest of the study entails. However, at the same time it is likely to be a place full of biases and misleading, inaccurate information presented in a manner that makes a study either more appealing or more dramatic.

Be very careful in taking an “abstract-only” approach to reading papers and reporting on said papers. Most articles are constructed with that notion in mind and may prey on the ignorance of readers to not do additional work or to spend time actually reading a study. It’s a general reminder that one should read before reporting.

Mathieu, et. al. provides an interesting perspective on this issue:

Medical practitioners have limited time to read articles and as a result, as Gotzche remarked, “Most users of the scientific literature read vastly more conclusions than they read abstracts, and vastly more abstracts than full papers. Conclusions are the worst part of papers,...” [19].

For me, I generally look at the abstract to see if a paper is worth reading and that’s about it. I try to not reference abstracts and by the time I actually read the study I find the abstract to be completely unnecessary— you’re already reading the study at that point.

You can, however, use the abstract as a frame of reference to see for yourself if the researchers may not be so forthcoming in their results. It’s sometimes a good way to see if a study is not being portrayed in an honest manner.

In short, use the abstract as a quick introduction to a study but be very cautious about the abstract being all there is to read in a study. When reading reports have a watchful eye and notice if the reporter or writer may have taken an “abstract-only” stance in their reporting as well.

3. Introduction Section

Introductions help ease a reader into the current study they are reading. It usually provides some background context to the study. If the particular study is about a disease such as SARS-COV2 you can generally find some information here. The same goes for a study on cancer, HIV, and other diseases.

You may also be provided some terminologies or definitions for specific words or phrases, which can help with the study especially if one group of researchers may use a different definition than another.

This is also where researchers will cite prior works as a basis for the current study. For instance, if the current study is a clinical trial for an experimental drug you’ll generally have reports from in vitro and animal studies cited here to provide the proper framework. Researchers may also cite their previous works here as well if they bear any relevancy.

The importance of introductions

There’s generally not much to say in regards to introductions aside from the fact that they provide the basis for the current study. For many readers unfamiliar to the work the introduction is a great place to look for citations and go down the rabbit hole of a specific topic. It’s also a good way to corroborate prior works and see if the the use of prior studies is accurate.

This is one place where checking citations will work to your benefit and gives you a chance to look up more information in case you may not have the proper knowledge to tackle the study you are looking at.

And if you are looking up studies on COVID I absolutely implore you, for your own sanity, to NOT read the first paragraph or two of an introduction unless you want to constantly read about “In December of 2019 a viral outbreak something something in Wuhan, China” or some other wording along those lines!

4. Materials & Methods Section

This is a section that gets overlooked very often, mostly because it requires knowledge of laboratory practices in order to properly parse the information. This can make this section very confusing even for people in similar fields as one molecular biology technique may differ quite extensively from another, and this same issue can happen across other fields as well.

Generally this section will outline the different instruments, reagents, and methodologies utilized in a study. If a study uses PCR they will tell you how the PCR was conducted here. Using specific cell lines? You’ll get information on the types of cell lines and how they were treated.

This is also where you will get information on dosing of a compound and even sample collection.

Overall, this section is highly technical and may require extensive background knowledge to look through. This is also why this section may be shuffled to the back of a paper where most people won’t see it (from what I can tell clinical trials with humans are likely to put the methods section near the front of a paper while in vitro studies are likely to shove it to the back).

I’ve personally had a very difficult time in looking through the methods section (as I’ve pointed out to Brian Mowrey on prior occasions), however this section can provide some of the most relevant information to a study.

For instance, this could be a place where someone finds out whether the study being conducted has any relevancy within the real world or may be extremely contextualized to the specific study.

The ADE study6 from last week has generally been reported as an indication that ADE is occurring from the vaccines. However, if you read the methods section (and what I’ve mentioned in my own post on the study) the cell line used was manipulated to overexpress both ACEII receptors and TMPRSS2 enzymes:

The procedure used to generate Mylc lines was previously reported38,39. Briefly, immortalized myeloid cell lines were established by the lentivirus-mediated transduction of cMYC, BMI-1, GM-CSF, and M-CSF into human iPS cell-derived myeloid cells. These cell lines were further induced to express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 using lentiviral vectors.

On its own the study would appear rather damning, however if you have to force cell lines to cause ADE to occur by overexpressing different receptors and enzymes could we really argue that ADE may be clinically relevant without further evidence?

One study that has been cited quite often by Ivermectic critics includes this one from Seet, et. al.7 as an indication that Ivermectin does not work as a prophylactic. I've even seen it used in meta-analyses and referred to as a good study to argue against Ivermectin.

However, aside from the fact that this was an open-label, unblinded study a peruse through the methods section would indicate that, in this monthlong prophylactic study the Ivermectin group was given Ivermectin only once (emphasis mine):

After randomization, each participant was supplied with a 42-day supply of the assigned intervention (except for ivermectin that was administered as a single dose) and was responsible for taking the medication as instructed without further direct supervision or observation by the study team. […] Although pharmacokinetic studies suggested a higher dosage of ivermectin (50- to 100-fold higher than approved limits) may be necessary to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication (Caly et al., 2020), sparse human data are available to support the safety and efficacy of ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2 at these doses. Given these uncertainties, we kept the dosage of ivermectin to within the approved limits of 200 μg/kg; a single dose of 12 mg was administered in participants who weighed >60 kg.

Now, to be fair the researchers weren’t trying to hide the fact that Ivermectin was only provided once in this study, yet this study was used as an indication that Ivermectin wasn’t effective, likely based on the results and discussion alone without having the proper context to understand a single-dose prophylactic probably isn’t going to be very effective, if at all.

These are just a few examples of when the M&M section may actually provide some context that puts studies into perspective.

Importance of the M&M Section

This is probably one of the most intimidating sections of a paper outside of the results. It’s very understandable that people would want to stay away from having to look here.

However, the M&M section can provide some much needed insights into a study. It may tell you whether the dosing of an intervention may be considered too low or too high for clinical use. It may also tell you whether there may be some aspects of the cells or tissues used that may not make sense, such as using cells from an organ such as the pancreas to infer infectivity from an upper respiratory virus in the lungs.

More importantly, this section is a good way of contextualizing a study in a broader context. If a study stands out as having results far different than the consensus the M&M section may be a good place to look to see how different studies may have used other methodologies. Also, if results appear strange or unusual, you can try turning to the methods section and seeing if researchers may have done something that led to the strange results.

5. Results Section

This is pretty much the meat an potatoes of a paper. This is where numbers, statistical significance, and figures will be thrown at you and leaving you disoriented, especially if you are unfamiliar with the units or the organization of different figures.

The results section is where the researchers put the findings from various experiments including any representative figures such as charts, graphs, or diagrams that would be relevant to a reader.

Depending on the study the Results section can be one of the most confusing parts because the figures may just be thrown in the middle of text that ambiguously may refer back to a figure without any additional explanation.

Usually, I tackle the Results section by corroborating the in-text information with the relevant figures. Let’s say the results mention that the use of an intervention reduced the viral load of SARS-COV2 and refers to a figure. You can then refer to that figure and see if the information is appropriate- is there a graph that shows exactly that happening?

In most cases many people may shy away from the figures because it may take a while to decipher what is being shown.

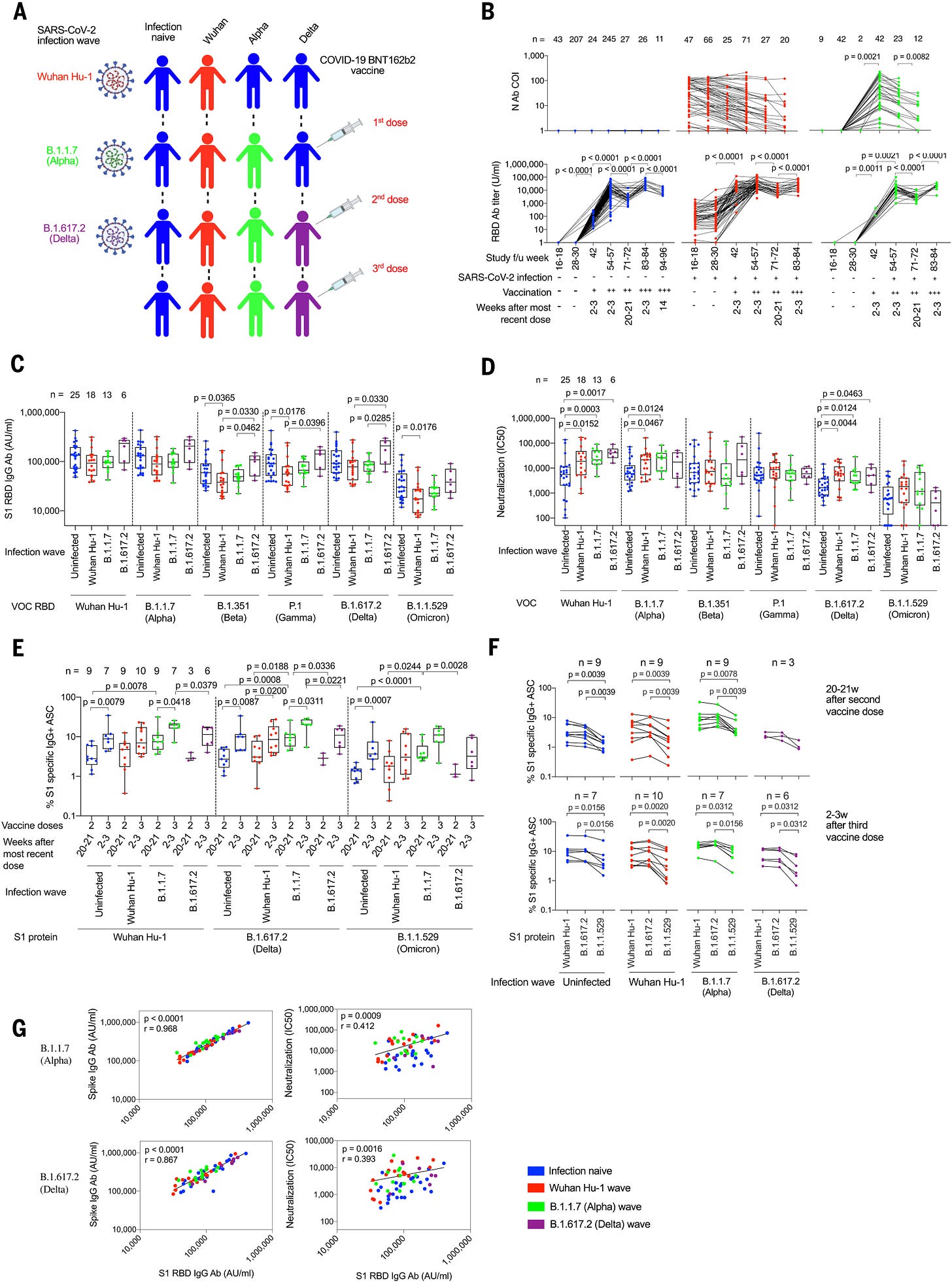

Here’s an example from a widely circulated Immune Imprinting paper8:

That’s a lot to take in right? And the study has plenty of figures such as this one, so you can understand why it took me a few days to get through this paper.

However, if there is a mismatch in the text of the article and the figures then that may clue people in that something may be misrepresented.

The results section is a good place to corroborate what is being said with the provided evidence. It also provides a guide to know where to look to see if the information makes sense.

For instance, here’s the in-text information in regards to part of this figure:

We found differences in immune imprinting indicating that those who were infected during the ancestral Wuhan Hu-1 wave showed a significantly reduced anti-RBD titer against B.1.351 (Beta), P.1 (Gamma), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) compared with infection-naïve HCWs (Fig. 1C). The hybrid immune groups that had experienced previous Wuhan Hu-1 and B.1.1.7 (Alpha) infection showed more potent nAb responses against Wuhan Hu-1, B.1.1.7 (Alpha), and B.1.617.2 (Delta) (Fig. 1D).

It’s a good idea to corroborate information one section at a time, such as looking at Fig. 1C first and seeing if you notice what the researchers are saying (hint: you’re going to want to look at the red data points and compare it to the other colored data points for columns 3, 4, and 6 from Fig. 1C and see if they are “lower” than the other colored data points).

I have raised concerns over this study before, and given the fact that the researchers speak rather ambiguously about specific topics and choose which results to compare a la carte always be aware that even the results may not cover the full scope of the studies that the researchers conducted. This is why an examination of the figures should be encouraged.

Here we may see that the text may only provide a “look here, not there!” assessment of their findings which may be more fleshed out by staring intently at the figures.

The Importance of the results

The results section is probably the most important part of the study. It’s here where all of the findings are shown and provides critical insights into a study.

Don’t be afraid to spend time looking at the figures and compare it to information within the written text. Sometimes information may either be misinterpreted or obfuscated when written down that would otherwise tell a different story in the figure.

Remember that the abstract and the discussion section draw from the findings in the results section. It’s here where one should find discrepancies between these sections. If both the discussion and the abstract are touting different results one must be very careful to understand that something may be afoot in order to obfuscate this discrepancy.

Most importantly, don’t be afraid to struggle in assessing figures or results. Many times I’ve found that I may struggle, come back, and reread the information several times over before I can create a cohesive thought. It’s also a good idea to write notes and extensively highlight different points including ones that are very confusing. Sometimes you may need a paper full of “??????” to start off before you can replace all of that confusion with actual information.

6. Discussion Section

The discussion section is where researchers interpret their findings in a broader context. It usually draws from prior works and sees how their new results fit into the broader scientific context. It also provides an avenue for future research and what other researchers should try and find.

This is a good place to start for many people who may find the results rather challenging to get through since it may provide a more simplified assessment of the results.

This is also where researchers are likely to discuss the limitations of their study.

However, be careful in remembering that the discussion section could be plagued by biases. A researcher who may be rather prideful may use this section as a way of overexaggerating the significance of their study. Results that may not look very good may also be overlooked, and in many cases results that may show very minimal differences may be reported differently.

Importance of the Discussion

Take discussion sections for their ability to provide a more simplified explanation for results and the reason why the results may be significant, while being careful in understanding some inconsistencies may be present. Be critical of studies that may discuss critical findings over other lukewarm or negative results.

A few more notes

This post has been intentionally broad in order to provide an overview. There’s more that could be discussed, and looking back I may not have been as personal in describing how I tackle studies.

No that there’s no “true” way to read a study. Some people such as Brian Mowrey may go directly to the methods to see how a study was conducted. Some people may just follow the organization of the paper and go from abstract to discussion.

I was taught during my undergrad that the route to read a study that tends to work out is the following:

Title → Abstract → Introduction → Discussion → Results → Methods

This route can work for people who may be overwhelmed by the results and methods. This allows one to slowly work their way to the more technical aspects of a study. But again, there’s no perfect way of tackling a study. Just keep in mind that no matter how you tackle a study it’s important that you spend time and try to make a good-faith effort to try an read and comprehend as much as you can about a study. In cases where you may be unsure it’s never wrong to be aware of your uncertainty.

To add on here’s a few more things worth considering:

Don’t fall for titles or abstracts- it’s worth remembering that the way that science is presented to the public is influence by the public itself. As such, publications are likely to use bombastic or dramatic terms and phrases in the title and abstract of papers. Be careful not to fall for these manipulative tactics when reading a study.

Don’t commit the sin of “abstract-only” reading- the abstract may be a good place to start, but be careful in thinking that the abstract is the only thing worth reading. Abstracts cannot cover the full scope of a study and may be designed in a way that intentionally covers up negative results or things that may not fit certain narratives.

It’s OK to struggle with a paper- no one has the innate ability to thoroughly read studies, especially within a matter of minutes. You’re more than likely to come across a study that may require additional background information or may be way above your technical knowledge. You’ll never be aware of your limitations if you are unsure of what limitations you have. Struggle with reading so that you can figure out your weak points and overcome them. Everyone had to start somewhere, so don’t pretend as if you have your capabilities all figured out.

You’ll never become a perfect analyzer- As much work you may put into learning how to read papers you’ll likely never become perfect. Heck, I would consider myself to still be a very amateur reader. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t make an attempt. Continue to get better and grow and so that reading doesn’t seem like an overwhelming burden.

If anyone has any questions or criticisms please feel free to comment them to me! I’d like to know what you all think of this article and if it’s useful or just overly general or banal. Also, if anyone knows of any helpful links that instruct on how to read papers that would also be great!

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Chaplin D. D. (2010). Overview of the immune response. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 125(2 Suppl 2), S3–S23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.980

Dagotto, G., Mercado, N. B., Martinez, D. R., Hou, Y. J., Nkolola, J. P., Carnahan, R. H., Crowe, J. E., Jr, Baric, R. S., & Barouch, D. H. (2021). Comparison of Subgenomic and Total RNA in SARS-CoV-2 Challenged Rhesus Macaques. Journal of virology, 95(8), e02370-20. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02370-20

Veiras, L. C., Cao, D., Saito, S., Peng, Z., Bernstein, E. A., Shen, J., Koronyo-Hamaoui, M., Okwan-Duodu, D., Giani, J. F., Khan, Z., & Bernstein, K. E. (2020). Overexpression of ACE in Myeloid Cells Increases Immune Effectiveness and Leads to a New Way of Considering Inflammation in Acute and Chronic Diseases. Current hypertension reports, 22(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-019-1008-x

Mathieu, S., Giraudeau, B., Soubrier, M., & Ravaud, P. (2012). Misleading abstract conclusions in randomized controlled trials in rheumatology: comparison of the abstract conclusions and the results section. Joint bone spine, 79(3), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.008

Efimenko, I., Nackeeran, S., Jabori, S., Zamora, J., Danker, S., & Singh, D. (2022). REMOVED: Treatment with Ivermectin Is Associated with Decreased Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: Analysis of a National Federated Database. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 116S, S40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.096

Shimizu, J., Sasaki, T., Koketsu, R. et al. Reevaluation of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection in anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic antibodies and mRNA-vaccine antisera using FcR- and ACE2-positive cells. Sci Rep 12, 15612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19993-w

Seet, R., Quek, A., Ooi, D., Sengupta, S., Lakshminarasappa, S. R., Koo, C. Y., So, J., Goh, B. C., Loh, K. S., Fisher, D., Teoh, H. L., Sun, J., Cook, A. R., Tambyah, P. A., & Hartman, M. (2021). Positive impact of oral hydroxychloroquine and povidone-iodine throat spray for COVID-19 prophylaxis: An open-label randomized trial. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 106, 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.035

Reynolds, C. J., Pade, C., Gibbons, J. M., Otter, A. D., Lin, K. M., Muñoz Sandoval, D., Pieper, F. P., Butler, D. K., Liu, S., Joy, G., Forooghi, N., Treibel, T. A., Manisty, C., Moon, J. C., COVIDsortium Investigators§, COVIDsortium Immune Correlates Network§, Semper, A., Brooks, T., McKnight, Á., Altmann, D. M., … Moon, J. C. (2022). Immune boosting by B.1.1.529 (Omicron) depends on previous SARS-CoV-2 exposure. Science (New York, N.Y.), 377(6603), eabq1841. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq1841

Thank you for a great post. This tenacity and attention to detail is why I read all your posts. (and Brian's)

I totally agree on going beyond the abstract. I find a significant number of abstracts to be purposely misleading. This might be because of the antivax nature of my interests, as studies that objectively demonstrate anti-covid-vax results might state a pro-vax conclusion that allows them to be published.

I usually read the title, abstract, figures and usually the whole article. If the article mentions vaccinated vs unvaccinated control group my interest is piqued and I always look at all data tables.

There were a couple of articles that contained data that allowed some unintended (by authors) conclusions and such things are always newsworthy.

I also often struggle with graphs or figures, which use abbreviations that I cannot understand, or do not explain what they are actually displaying etc. I am glad that I am not alone. I thought I was.

I do suffer from attention deficit and am constantly distracted by people and that is terrible for attentive article reading, so I struggle in this department but try to at least make sure I understood what the article is saying. Sometimes I feel to be intentionally being confused.

This is where I am grateful to people who dig extra deeply into articles, like you do. It is very refreshing.

The M&M section is something that I usually ignore due to not having lab knowledge.

Thank you for an amazing post

Great post. I would add to this the importance of the supplementary indexes where sometimes key results are hidden w/o comment.

Also Conflict of Interest and Funding sections