Has rhubarb been given a bad rep?

An early comer of spring is also known to be fairly toxic. But is this a well-earned connotation or overblown misattribution?

I know, this article is something that is a few months too late- rhubarb season starts in early Spring! This was an article that I worked on off and on just to provide something seasonal, but due to work and other obligations I wasn’t able to finish it in time. Here is my long-winded post on something that many people may not be interested, although I will argue that it’s an interesting glimpse into how we can just take things as fact without looking into claims for ourselves. Here is an article on rhubarb but this need to do your own research extends to even more important topics.

While walking along a trail during my lunch break a coworker and I came across several plants just strewed along edges of the path. Curious to see what these large, almost Jurassic-like plants were we checked using a plant app and realized we were looking at none other than rhubarb just hanging out.

Among some of the early spring bloomers is this well-known, celery lookalike.

I have never tried rhubarb, but it appears to have quite the reputation as a vegetable-made-fruit delicacy, especially in strawberry rhubarb pies and other tart pastries, earning it the nickname “pie plant”. But along with its use in dessert rhubarb is also widely known as being quite toxic, with many people warning against consuming the leaves in particular. This is one of those things that I have always heard about, and I’m sure plenty of my readers have as well (it’s probably the first thing people mention when talking about rhubarb).

But given that it may be rhubarb season why not take a gander and see if the fears over rhubarb are warranted or possibly an old wives’ tale.

History

Rhubarb’s history, surprisingly, can be traced all the way back to China where it has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. Some of the earliest accounts of rhubarb’s medicinal use appears in the book Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, one of a handful of works referred to as materia medica (material medicine) and serves both as a pharmacopeia of medicine as well as one of the most influential works regarding medicinal plants.1 Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing details many medicinal plants that were in use during the Han dynasty, categorizing them based upon their medicinal properties as well as their toxicities. It seems that rhubarb was used for its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, and this use (along as a possible anticancer agent) continues to this day.2

In addition, it appears that rhubarb’s early sprouting period stems from where it typically grows in China in which the regions with native rhubarb tended to contain cool/temperate, moist climates.

How rhubarb made its way into the western world is not very clear. It’s been suggested that Magellan came across rhubarb while in China, although this doesn’t tell of how rhubarb became popular in the US and western Europe.

One article from Michigan State University suggests that rhubarb was brought to the US by Benjamin Franklin:

Folklore credits Benjamin Franklin with bringing rhubarb to America in the late 1700s. However, it wasn’t until the late 18th or early 19th century that Great Britain and the United States started using it for culinary purposes. Prior to that, it had been cultivated in Asia for over 5,000 years and used for medicinal purposes.

This claim seems unsubstantiated, and is partially contradicted by an article from the University of Madison-Wisconsin which details an earlier introduction as a food source as compared to the MSU article:

The English were the first to eat rhubarb, beginning in the 17th century, but unfortunately chose to begin with the leaves that look like chard. The leaves, however, contain a toxic amount of oxalic acid and are poisonous. The ensuing cramps, nausea and sometimes death from ingestion suppressed interest in the plant for about two hundred years. But by the late 18th century Europeans had discovered that the tart stalks were the part to eat – perfect for “tarts” giving rise to the nickname “pieplant.” It was brought to the Americas by settlers before 1800.

There’s also some evidence that the Greeks used rhubarb as laxative thousands of years ago, suggesting a use like the Chinese as a form of medicine. Interestingly, this may be where rhubarb got its name as rhubarb appears to be derived from the Greek words rha barboron.

Barbaron is where the word barbarian is derived from and refers to those who are non-Greek (apparently within the context that foreigners sounded like they were speaking babble), and rha may refer to the Greek name for the Volga River- Rha. Rha itself may be a reference to sellers/traders who traveled along the Volga River and brought rhubarb to Greece. Thus, the two words together may refer to Chinese travelers who came along the Volga River and brought rhubarb- note that this is just an assumption on my part based on some of the scant information available.3

Irrespective of how rhubarb came to the west it certainly appears that this is where rhubarb earned its culinary use due to the tartness associated with the stalks of the plant.

A tale of toxicity

You’ve likely been told to avoid the leaves of rhubarb due to their high toxicity-it is the purpose of this review after all!

The offending molecule in question appears to be Oxalic Acid.

Oxalic acid is a very small molecule, comprised of an ethane backbone with carboxylic acid groups on both ends.

Many foods contain oxalic acid, and we produce oxalic acid as a byproduct of metabolism as well, so it’s a rather commonly found compound.

Dominant sources of oxalic acid include chocolate, spinach and other leafy greens, tea, potatoes, parsley, and coffee. Therefore, we’re likely to be exposed to oxalic acid quite often through our diet.

Plants appear to use insoluble calcium oxalate as a means of aiding in many cellular functions including photosynthesis and and tissue support while soluble forms of oxalate help to remove heavy metals and aid in preventing senescence.4

Usually oxalic acid exists in its deprotonated form as oxalate where the two hydrogens from the carboxylic acids are stripped away leaving two highly negatively-charged regions of the molecule. The high electron density makes oxalates good chelating agents in that oxalate binds very well to cationic metals.

In particular, oxalate binds very well to calcium ions, and can actually remove calcium from circulation at very high levels as calcium oxalate complexes are rather insoluble.

This mechanism has categorized oxalate as an anti-nutrient as it can deplete vital minerals from the body.

This contributes to some of the side effects of excess oxalates. As oxalates bind to minerals they can aggregate and result in a process known as hyperoxaluria, or excess oxalates within the urine. At higher levels oxalate/mineral complexes can aggregate resulting in kidney stones.

Unfortunately, there’s not much regarding symptoms of excessive dietary oxalate. Most symptoms listed online refer specifically to industrial use of oxalic acid in which people are likely to be exposed to very high doses through various means such as inhalation or skin exposure.

Instead, it is possible that some symptoms of oxalic acid toxicity are not related to oxalate itself but rather the depletion of available calcium- an element which is critical for nerve function, cellular signaling, and other bodily functions.

So, this may account for some of the issues regarding rhubarb leaves. But if oxalic acid is found in multiple foods, and if the symptoms aren’t a concern for most people until eaten at high doses and chronically is there a real concern regarding rhubarb leaf toxicity?

Case Reports of Poisonings

A look into rhubarb will take us into the past where many of these tales of death and tragedy come from, and from which we may get some of our notions on rhubarb toxicity.

Some of the earliest accounts I came across regarding the consumption of rhubarb leaves includes an article from 18455 pointing to a family who boiled the leaves and ate them, with vomiting ensuing soon afterwards:

Several reports note nausea and cramps after consuming rhubarb leaves, but these accounts are muddied with other symptoms which makes it difficult to ascertain the veracity of these claims. Note that articles such as the one from MSU and from other parts of the internet suggest that there have been deaths associated with rhubarb leaves.

One story that seems to have popularized this idea came from accounts of British World War I soldiers who were recommended to eat rhubarb leaves due to food shortages. It appears that illness ensued among the soldiers with a few supposed accounts of a soldier dying. I haven’t been able to find the actual article but several correspondences have been published citing these alleged deaths such as the one below from 19196:

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find the original source and so these claims cannot be verified- we’ll live this as one case that can’t be substantiated.

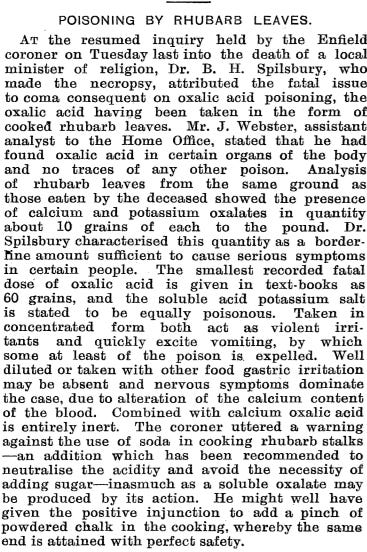

There is also note of a minister who appeared to have died due to rhubarb leave consumption in 19177 per a coroner’s examination:

This report is rather strange given the comment about the minister falling into a coma after consuming the cooked rhubarb leaves. There doesn’t appear to be any account noting someone falling comatose that I could find. This raises questions regarding whether other circumstances could have led to the minister’s death which weren’t accounted for, with an examination strangely focusing only on the circumstantial evidence regarding the rhubarb consumption.

This is reflected in a comment provided in the 1919 JAMA article in which the cause of death of this minister is put into question:

Remember that the coroner’s report for the minister noted oxalates throughout the body, but oxalates themselves are a byproduct of certain metabolic pathways and could be related to other food sources aside from rhubarb. Thus, the presence of oxalates themselves may not suggest oxalate-related poisoning and death. In addition, remember that dietary oxalates may form insoluble calcium oxalate complexes which are the main cause for concern, of which doesn’t appear to be present in the coroner report as well (again, as mentioned in the above comment) even though this would be rather recognizable.

It’s also interesting that the article references the eating of stems as accounting for most rhubarb poisonings given that the stems are the part that is widely consumed- it’s the leaves that people are cautioned against consuming.

And even then, oxalic acid isn’t entirely a strong toxin. The supposed LD50 of oxalic acid is relatively high based on evidence from animal models and one reported lethal case in a human:

LDLo refers to the lowest dose of a compound that has been reported to be lethal, and so there appears to be one case reported of a lethal consumption of oxalic acid that amounted to a dose of around 600 mg/kg. For a 100 kg male that would amount to 60g of oxalic acid that would need to be consumed.

We’ll examine the oxalate content of rhubarb further on, but in general note that a good deal of oxalate needs to be consumed be consumed in order to produce lethal effects.

One more case report of old that’s worth considering is one mentioned in the comment above debunking the minister’s cause of death.

The comment makes mention of an incident in which “epitaxis and noncoagulation of the blood” occurred with one individual, which also included an unfortunate abortion.

The case seems to refer to a house visit made in 19198 to an unwell woman who would eventually die, with evidence of noncoagulating blood and an unfortunate abortion appearing to have taken place over the course of a morning:

It was noted that Mrs. A cooked up some rhubarb leaves the night prior and had it for supper, of which Mr. A took very little of:

It’s again interesting that this is another account of someone possibly having side effects from eating the stalks, although a good degree of context is missing here.

But the stranger phenomenon here is the noncoagulating blood which has been mentioned several times. This, again, is another symptom that doesn’t appear to be mentioned within the literature aside from this case.

Here the visiting doctor appears to suggest that noncoagulating blood is tied to the oxalates from rhubarb.

However, there may be a more viable explanation for the noncoagulation:

Acetylsalicylic acid is also known as aspirin- an OTC medication that can also act as a blood thinner. We aren’t provided any information regarding how much aspirin Mrs. A took, but when comparing the symptoms it seems more plausible that the lack of coagulation could be due to the use of aspirin rather than the oxalates that Mrs. A ingested. It appears her pain came in waves, and so it’s possible that she turned to aspirin whenever her pain arose and continued to do so throughout the day. The association of these symptoms to aspirin is made more likely given that symptoms of aspirin toxicity also include rapid breathing and heart rate- both of which are described in the above case.

Other circumstances could be at play here, but for the most part it seems very unlikely that Mrs. A’s death could be directly attributed to the rhubarb she consumed as other circumstances are likely to have caused her untimely death.

So based on some of the reports alone we can see that there’s a lot of speculation taking place regarding the link between rhubarb consumption and death. In the cases mentioned above it’s clear that other factors were likely at play that could have explained the deaths in question, and in some of the incidences the evidence provided did not appear compelling.

It’s rather interesting to consider how much influence such reports can have on our modern day perception of foods. Note that a lot of these reports seem to cite one another in detailing rhubarb-related deaths and yet every death seems to come with their own confounding variables. All of these reported cases appear to have come out around the same time period as well, which may make one wonder if the timing caused a bias towards fears over rhubarb.

And in some instances of more recent reporting the cases don’t appear to be accessible, such as this apparent report from 1960 of a child’s alleged death after eating rhubarb leaves.9

I have personally never heard of “death from rhubarb” as being a driver of the fear mongering, but it’s also plausible to consider that many of our current perceptions may have been poisoned by poorly evidence reports from years ago.

How much oxalate is in rhubarb?

This is probably the most important question to ask when it comes to rhubarb’s leaf toxicity. If oxalate is found in other plants then isn’t it possible that other plants may be harmful as well? This is why relativity is important- what frame of reference can we use to better gauge the actual toxicity of rhubarb leaf-derived oxalates.

Unfortunately, the evidence here is just as muddled as anything related to death from rhubarb.

This is due to the fact that quantification of oxalate depends upon many variables including the type of rhubarb analyzed, the method of oxalate extraction, and the analytical method used. Studies may also examine the entire rhubarb plant rather than separating the leaves from the stalks. Because of these factors there isn’t any clear measure of oxalate content.

Oxalate content in rhubarb can also differ based upon sunlight exposure, soil content, region where it is grown, water availability, etc.

One article from 199910 provides the following table and comparisons of oxalates from rhubarb and other foods:

There’s no information stating where these numbers came from, and note that the range of values for some of these plants are very wide. From this table alone spinach, cocoa, and tea may also be foods of concern given their high oxalate content.

One cited article from 200911 provides a more conservative estimate wherein rhubarb oxalate content seemed far higher relative to other foods:

Although the text mentions higher oxalate content within leaves as compared to the stalks the adapted table above doesn’t separate the content of the two, and therefore doesn’t provide an available comparison.

You can find many websites with their own measures of oxalates but again bear in mind that those values can come from anywhere. It seems as if rhubarb as a whole may be relatively higher in oxalates as compared to other foods, but also many more commonly consumed foods such as spinach also appear relatively high in oxalates so it’s curious why rhubarb has been given the bad rep.

But how does this compare to lethal doses? If we consider the LDo mentioned above for a woman to be 600 mg/kg oxalate relative to bodyweight let’s assume a typical women weighs around 60 kg. That’s about 36,000 mg (or 36 g) of oxalate needed to kill a woman at this weight.

Even if we take a conservative estimate of 1 g of oxalate per 100 g of rhubarb that would mean someone would need to eat 3,600 grams of rhubarb (3.6 kg or near 10 lbs) in order to have a possibly lethal dose. Of course, we’re not taking into account the fact that rhubarb values may not be based on leaves, but from here we can see that a pretty good deal of rhubarb needs to be eaten in order to experience anything close to death, once again bringing into question the reported deaths above.

And a lethal dose wouldn’t need to be considered if one were to consider side effects in general which could occur at far lower exposure levels.

It may not be the oxalates…

Strangely, most of the concern regarding rhubarb toxicity has focused on the oxalate content of rhubarb leaves. However, rhubarb is also rich in many other compounds, with some of these compounds appearing to have their own issues as well.

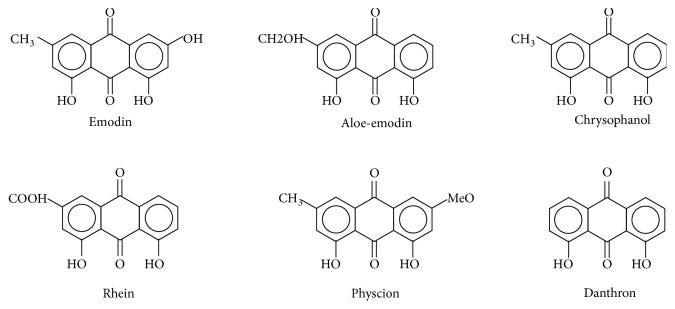

For instance, many researchers are investigating the benefits of a group of compounds derived from rhubarb known as anthraquinones. Anthraquinones are a class of aromatic, tricyclic compounds that appear to confer many of the health benefits of rhubarb. In particular, Emodin12 and Rhein13 appear to be anthraquinones of high interest for researchers:

As of now researchers are examining these anthraquinones for their neuroprotective14, cardioprotective15,16 and anticancer17 properties.

What’s also interesting is that anthraquinones are known to have a laxative effect on the body leading to their use as in laxatives and as a method of losing weight. This may explain the Greeks use of rhubarb as well as its use in Chinese medicine.

The laxative effects appear to be derived from microflora-related anthraquinone metabolites which induce colonic activity, but it’s through here where some anthraquinone-related toxicities can be seen as anthraquinones are associated with darkening of the colon called melanosis coli. This has raised some concerns about the possible association between melanosis coli caused by anthraquinones and the increased risk of colon cancer.

Questions have also been raised regarding nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity associated with anthraquinones derived from herbal supplements, bringing into question whether rhubarb-derived anthraquinones can come with their own toxicity profile as well.18

This can be seen in a comment from Xiang, et al. regarding the safety rhubarb:

Preclinical studies have shown that rhubarb has toxic effects on the liver and kidneys and is associated with cancer risk. Emodin, the main causative agent of rhubarb hepatotoxicity [96], can cause apoptosis in normal human L02 cells and increase the expression of liver injury markers [97]. In addition, emodin can affect the oxidative phosphorylation pathway by inhibiting the activity of all mitochondrial complexes, which causes mitochondrial damage, decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS), adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis disorder, and finally liver cell apoptosis [98]. In addition, oral rhubarb or rhubarb products pose a risk of nephrotoxicity due to the abundance of oxalates and anthraquinones, which can lead to deterioration of kidney function as a result of oxalate excretion disorder and crystal deposition in the kidney [99].

But as Xiang, et al. emphasizes these issues seem to be a bigger concern for those with impaired kidney/liver function or children, and evidence of these harms generally occur with high-dose, prolonged use of anthraquinone-based products such as supplements which may have concentrated forms of anthraquinones relative and oxalates relative to fresh plants.

So it’s possible that several rhubarb-derived compounds may be responsible for the toxicities, although each compound comes with its own degree of ambiguity.

Don’t fret over a few leaves

A few leaves isn’t something to throw a dish out over. Paranoia over removing leaves doesn’t appear to be warranted and and you don’t have to get yourself worked up to try to avoid any bit of leaves as possible.

That being said don’t use this article as justification to freely eat as many rhubarb leaves as you want- although a good deal is needed to become fatal rhubarb leaves can likely still cause gastrointestinal upset, and for those at higher risk of kidney stones as well as kidney/liver disease more caution should be taken to avoid the leaves. Care should also be taken for children who may experience the toxic effects as their lower body weight may make them more susceptible to the toxic side effects.

However, the point of this article is to focus on an often repeated but seldom researched comment regarding rhubarb being poisonous. Like with many things we have been told we may generally trust but never verify any of these comments.

For something like rhubarb this research may appear rather trivial- is anyone really concerned about rhubarb being poisoned? But if not rhubarb then it could be anything else that we are told is factual but without any context.

Like with prior articles the point here is to take some bit of information that is generally passed around and check for ourselves to see where this information comes from. It allows us to look into the past and understand how bits of spurious information can result in widespread hearsay based on poor evidence.

Anyways, enjoy your rhubarb without too much concern! And let me know of your experiences with rhubarb. Again, I’ve never tried it so I’m curious how many people enjoy rhubarb.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Zhao, Z., Guo, P., & Brand, E. (2018). A concise classification of bencao (materia medica). Chinese medicine, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-018-0176-y

Xiang, H., Zuo, J., Guo, F., & Dong, D. (2020). What we already know about rhubarb: a comprehensive review. Chinese medicine, 15, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-020-00370-6

The etymology of rhubarb was derived from an article published by Bon Appetit, however I’m unsure where Bon Appetit got its information.

Li, P., Liu, C., Luo, Y., Shi, H., Li, Q., PinChu, C., Li, X., Yang, J., & Fan, W. (2022). Oxalate in Plants: Metabolism, Function, Regulation, and Application. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 70(51), 16037–16049. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c04787

Oxalic Acid in Rhubarb or Pie Plant. (1845). The Buffalo medical journal and monthly review of medical and surgical science, 1(1), 19.

Leffmann H. "DEATH FROM RHUBARB LEAVES DUE TO OXALIC ACID POISONING". JAMA. 1919;73(12):928–929. doi:10.1001/jama.1919.02610380054023

POISONING BY RHUBARB LEAVES. (1917). The Lancet, 189(4892), 847. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)28923-5

DEATH FROM RHUBARB LEAVES DUE TO OXALIC ACID POISONING. JAMA. 1919;73(8):627–628. doi:10.1001/jama.1919.02610340059028

As an example of how much science has changed from over a century ago take a look at this article that was also included in the oxalic acid report where doctors were arguing if gonorrhea was incurable:

TALLQVIST, H., & VAANANEN, I. (1960). Death of a child from oxalic acid poisoning due to eating rhubarb leaves. Annales paediatriae Fenniae, 6, 144–147.

Noonan, S. C., & Savage, G. P. (1999). Oxalate content of foods and its effect on humans. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 8(1), 64–74.

Barceloux D. G. (2009). Rhubarb and oxalosis (Rheum species). Disease-a-month : DM, 55(6), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.03.011

Stompor-Gorący M. (2021). The Health Benefits of Emodin, a Natural Anthraquinone Derived from Rhubarb-A Summary Update. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(17), 9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179522

Zhou, Y. X., Xia, W., Yue, W., Peng, C., Rahman, K., & Zhang, H. (2015). Rhein: A Review of Pharmacological Activities. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2015, 578107. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/578107

Li, X., Chu, S., Liu, Y., & Chen, N. (2019). Neuroprotective Effects of Anthraquinones from Rhubarb in Central Nervous System Diseases. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2019, 3790728. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3790728

Guo, Y., Zhang, R., & Li, W. (2022). Emodin in cardiovascular disease: The role and therapeutic potential. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 1070567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1070567

Liudvytska, O., & Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. (2022). A Review on Rhubarb-Derived Substances as Modulators of Cardiovascular Risk Factors-A Special Emphasis on Anti-Obesity Action. Nutrients, 14(10), 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102053

Huang, Q., Lu, G., Shen, H. M., Chung, M. C., & Ong, C. N. (2007). Anti-cancer properties of anthraquinones from rhubarb. Medicinal research reviews, 27(5), 609–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/med.20094

Xu, X., Zhu, R., Ying, J., Zhao, M., Wu, X., Cao, G., & Wang, K. (2020). Nephrotoxicity of Herbal Medicine and Its Prevention. Frontiers in pharmacology, 11, 569551. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.569551

Chop up a bunch of fresh rhubarb stalks. Put in a pan and just cover with filtered water. Simmer gently until rhubarb is completely soft and water is mostly evaporated. It will look similar to apple sauce. Add sugar to taste. Serve over vanilla ice cream.

I live in the famous Rhubarb Triangle. Grown in fields and early crop grown in dark sheds, only lit by candle light when pickers go in. They say they can hear the rhubarb growing. As kids, we'd help ourselves to some field grown stalks which we ate raw after dipping in a paper bag of sugar. A dipping sherbet! wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhubarb_Triangle Mothers would bake crumbles, chefs use with meat and latest trend is making Gin liquers with it. Taught early to discard leaves too.