Great, so is green tea bad for us now too?

Several outlets have jumped onto a claim that green tea may be hepatotoxic, but how much truth is there to this claim?

In the past few days I’ve seen several articles suggesting that green tea may actually be dangerous. In this case, several articles have suggested that green tea consumption may be associated with liver injury, including liver failure.

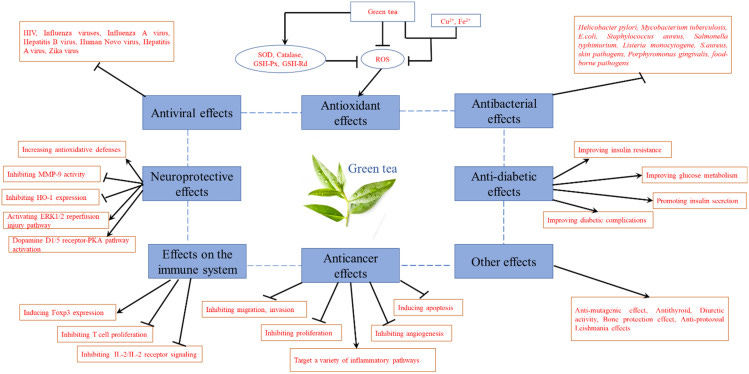

Green tea has become an extremely popular beverage, usually noted has having high levels of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties, leading green tea to be associated with health foods.1

So it’s rather strange to consider green tea as being toxic. When these sorts of studies come out I consider it from the perspective that these studies are intended to be contrarian, rebutting prevailing notions in science.

Although green tea as a drink has become rather popular, supplements containing green tea extracts have become popular in recent years as well. In this case, the health benefits of green tea extracts usually aren’t related to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, but due to reports that green tea extracts may help with weight loss.

Dr. Oz is probably known as being one of the most well-known doctors to suggest green tea as a possible weight-loss agent, suggesting both the drink as well as the supplement form on several occasions on his daytime show:

But with how widespread consumption of green tea is, could one really argue that there are serious risk of liver injury?

The evidence for the articles above appear to have come from a 2022 review from Malnick, et al.2 It would appear as if many outlets have reported on this topic because they saw others who did, and likely jumped onto the bandwagon. It’s an example of a topic becoming popular by virtue of people reporting on said topic, thus artificially inflating its significance.

The review, strangely, is extremely short, and really doesn’t offer much in a way of explaining the hepatotoxicity of green teas, and appears to assert that the hepatotoxicity associated with green tea may be due to the mixture of green teas with other additives, the purity of the water used, and individual differences which may influence whether one is more inclined towards hepatotoxicity.

One of the only noteworthy comments is related to the cause of this hepatotoxicity, which appears to suggests that some compounds, most notably furan-containing terpenoids, may be metabolized by P450 liver enzymes into reactive intermediates. It’s these interactive intermediates which may target liver cells and induce hepatotoxicity by serving as an electrophilic intermediate for cysteine residues of biomolecules, possibly in a manner akin to how acetaminophen may induce liver toxicity.

This may explain why toxicity may take a while to accumulate, as over-exposure to these furan-containing compounds may deplete glutathione levels and induce liver injury.

However, it appears that these terpenoids are related to a plant named germander rather than green tea. It appears that weight-loss supplements and green tea mixtures may contain germander to aid in losing weight. It’s this plant that provides the hepatotoxic terpenoids as noted in a review from Chitturi, S., & Farrell, G. C.3, which is also one of the citations provided in the Malnick, et al. review:

Germander toxicity is attributed to reactive metabolites (epoxides) generated by CYP3A metabolism of its constituent neoclordane diterpenoids (chiefly Teucrin A).28 In rat hepatocytes, these epoxides can deplete hepatic glutathione and cytoskeleton-associated protein thiols. These processes culminate in the formation of plasma membrane blebs and apoptosis. However, other lines of evidence implicate immune-mediated pathways in initiating liver injury. When rechallenged with germander, a rapid rise of serum transaminases was observed in approximately half of these cases. In other cases, autoantibodies (antinuclear, smooth muscle and antimitochondrial M2) were present.29 In particular, a specific autoantibody (antimicrosomal epoxide hydrolase) was identified from sera of long-term drinkers of germander tea. The target for this autoantibody is an epoxide hydrolase on the hepatocyte surface.30

So even in this case the evidence cited appears to be related to additives included in weight-loss products that appear to be the main hepatotoxin.

As noted, the review from Malnick, et al. provides scant evidence of actual hepatotoxicity related to green tea, merely serving to speculate on such possibility and providing some explanations for this possible occurrence.

One of the only examples of hepatotoxicity comes from the following excerpt (emphasis mine):

There is, however, a potential danger associated with an increase in green tea consumption. The liver can suffer injury from drugs (drug-induced liver injury (DILI)) and herbs (herb-induced liver (HILI)). HILI has been linked to green tea consumption.

Since MAFLD is associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome and green tea is advertised for weight reduction, it is to be expected that there will be a large increase in the number of obese individuals receiving green tea.

Green tea extracts have been linked to several cases of hepatotoxicity and exacerbated by fasting. In a mouse model, decaffeinated green tea extract did not cause hepatotoxicity [19].

There are more than 100 cases of hepatotoxicity related to green tea extract in the literature and summarized with Liver Tox. The US Pharmacopeia reported a systematic review of green tea extracts [20]. The GTE composition and catechin profile differ between varying manufacturing processes. The USP review found hepatotoxicity to be related to epigallocatechin (EGCG) in daily amounts ranging from 140 mg to 1000 mg. There was interindividual variability in susceptibility which could reflect genetic factors. Decaffeinated green tea did not cause hepatotoxicity in a mouse model [19].

But aside from a few other ambiguous comments not much explanation was provided.

However, this led me to look into the literature to corroborate the claim of green-tea hepatotoxicity.

One of the largest reviews on green tea hepatotoxicity comes from a 2020 comprehensive United States Pharmacopeia review4. USP is considered to be a 3rd party entity that checks the purity of various supplements on the market. You may have heard of them in Nature Made commercials as being the entity that checks for the purity of Nature Made products and provides a USP-verified seal.

In this review USP looked for cases of hepatotoxicity related to green tea extracts (GTE). Note that in this case they are looking at extracts, and not at green tea as a beverage.

Thus, it likely points to a dosage factor in green tea’s toxicity, in which more concentrated forms may increase the risk of liver injury.

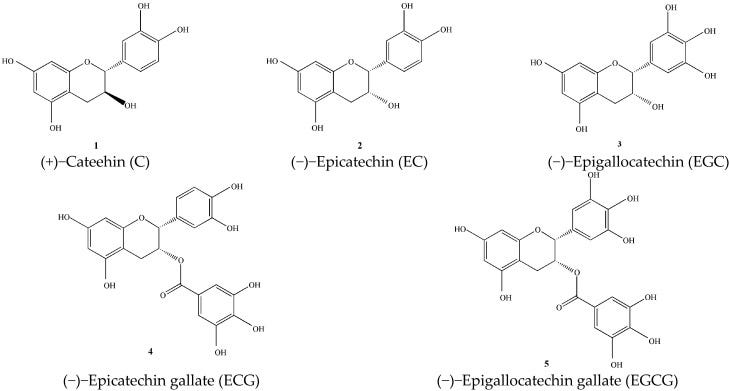

In this case, the toxicity related to green tea appears to be associated with compounds called catechins.

Catechins are a group of polyphenols suggested to have anticancer and anti-inflammatory properties. They are considered to be one of the most beneficial compounds found in green teas, and research has looked into possible uses of catechins as therapeutic agents, which is rather interesting given the context that they may be related to incidents of hepatotoxicity.

Several catechins are shown below from the Zhao, et al. review:

EGCG has been looked at rather extensively, mostly because purified GTE products may isolate EGCG in particular. It’s also worth noting that catechins are not found in green tea alone, but are also found in coffee and berries as well.

The 2020 USP review notes several cases of liver toxicity, but in here the examples are confounded by lack of dosage data as well as the possibility of synergistic effects derived from weight-loss supplements.

When examining some of these case reports of hepatotoxicity the USP team noted the following (DILIN is Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network, emphasis mine):

DILIN experts concluded that there was positive liver injury in 29 cases (Table 5), scoring them as probably related to GTE (14 cases), highly likely related to GTE (11 cases) or definitely related to GTE (4 cases). Only four cases that had positive de-challenge and positive re-challenge were scored as definite.

Twenty-six cases involved concentrated GTE, nineteen of which excluded the involvement of other drugs. One case involved a 46-year-old woman who developed jaundice and had severe hepatocellular injury seven months after starting daily intake of extracts of Chinese green teas. Other possible causes such as underlying liver disease were ruled out. The amount of GTE used was not provided in the article. One of the authors, HL Bonkovsky, who was among the DILIN experts performing causality assessment in this review, communicated that all alternative explanations were reasonably ruled out and that the latency and recovery and clinical picture were typical of GTE hepatotoxicity [6].

The Molinari case [146] involved a 44-year-old white woman who took 720 mg of GTE daily for 6 months and developed fulminant liver failure. All other possible causes were ruled out, and her liver injury was typical of other reported GTE-induced DILI in that the liver showed severe, albeit variable, hepatic necrosis with areas of relatively preserved hepatic parenchyma, areas showing centrilobular (zone 3) necrosis and bridging necrosis, and in other areas, panlobular or multilobular necrosis.

The Porcel case [148] of a 53-year old female who ingested 3 capsules daily of Fitofruit grasas acumuladas (the label indicated the product contained GTE but the amount was not provided) for 2 weeks one month prior to her liver injury also ruled out other risk factors such as hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and lacked serologic evidence of auto-immune liver injury (negative antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies). However, no medical history was provided, and the course of illness was not clearly outlined.

Four cases were part of a case series reported by Björnsson and Olsson in 2007 [130] involving the intake of Cuur®, an herbal weight-loss supplement containing 82 % ethanolic dry extract of green tea leaves. The duration of treatment before the manifestation of liver injury was 5–20 weeks, although the amount of extract ingested was not provided. Twelve of the cases involved the use of Exolise®; (Arkopharma), which, as already mentioned, reportedly caused liver injury and was subsequently banned in France and Spain in 2003 [42,43].

In the case reports provided there did appear to be an association between GTE and hepatotoxicity, with other possible causes ruled out. However, there were still inconsistencies in exposure in the provided reports. A lack of quantitation of GTE exposure suggests that a toxic dose of catechins could not be provided, leaving room for other variables as well, such as the purity of the green tea and supplements, which may contain contaminants such as pesticides or heavy metals. There’s also an issue of inconsistent labeling of actual ingredients or catechin levels. Supplements, if used for weight-loss, may also contain additives that may have a synergistic effect on liver damage.

The authors note the following in the Discussion:

The human cases reviewed herein involved the use of preparations containing green tea in a wide range of doses. GTE intake amounts ranged from 500 mg to 3000 mg which is about 250−1800 mg EGCG daily). The median intake amount was estimated at 720 mg/day (delivering 623 mg of EGCG daily). In most cases, the GTE had been taken daily for two or more weeks before onset of the acute liver injury, which in some cases occurred up to a month after stopping the intake of GTE. Most subjects involved in the DILI cases (21 out of 35) were using GTE for weight loss and likely had reduced food intake as well. This may be significant given the increased hepatotoxicity of EGCG preparations in fasted compared to fed dogs [107]. Individuals trying to lose weight are also likely be eating less food which may inadvertently mimic fasted conditions resulting in significantly increased bioavailability of EGCG.

Catechin absorption appears to be related to food intake, in that bioavailability increases in a fasting state. Thus, as noted above, the toxicity of catechins may also be related to the use of supplements in a fasting state, which may increase circulating levels of catechins. The use of GTE supplements for weight-loss may also occur with reduced food intake which may increase the effects of catechins, with both factors have a possibility of contributing to elevated catechin levels and liver injury.

No to green tea? Well, maybe just supplements…

There does appear to be a few incidences of liver injury and liver failure in the literature, but in many of these cases the injuries don’t appear to be associated with green tea as a beverage, but rather with more concentrated forms that may have been doctored for use as a weight-loss supplement. It can’t be ruled out that people who are taking GTE for weight-loss may also be taking other supplements as well and may have some influence on hepatotoxicity.

In many of these case reports the hepatotoxicity appears to have occurred predominately in woman, which may suggest the use of GTE-containing weight-loss supplements, as well as a sex-based component for the liver injury.

Overall, the available information is rather interesting. I came into this thinking there would be absolutely no evidence of hepatotoxicity. Although the cases appear to be few relative to the actual number of people who consume green tea, and are likely influenced by additional factors, there are a few cases noting a correlation.

This is an important reminder that things that are natural aren’t inherently safe. As the saying in pharmacology goes, it’s the dosage that makes the poison.

So for most people the consumption of green tea as a beverage likely won’t be a big concern, although high quality tea should be used if possible.

However, given the uncertainties of GTE supplements, care should be taken to be aware of catechin levels, as well as any issues in manufacturing and improper labeling. It’s an important reminder that people should pay more attention to labels and understand what they are putting into their bodies.

Green tea likely won’t go away, and given all of their health benefits it would probably be absurd to assume that people will stop consuming green tea in general. If there was any takeaway to garner from this post, it would be that less-processed green tea, as in the form of dried tea leaves used to make drinks, may be the best approach rather than relying on supplements which may be doctored or contaminated.

As the sayings go, all things in moderation, more may not always be better, and be aware of any changes to your body and where they may stem from.

Also, always ask a medical professional for more information!

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Zhao, T., Li, C., Wang, S., & Song, X. (2022). Green Tea (Camellia sinensis): A Review of Its Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(12), 3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123909

Stephen Malnick, Yaacov Maor, Manuela G. Neuman, "Green Tea Consumption Is Increasing but There Are Significant Hepatic Side Effects", GastroHep, vol. 2022, Article ID 2307486, 5 pages, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2307486

Chitturi, S., & Farrell, G. C. (2008). Hepatotoxic slimming aids and other herbal hepatotoxins. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 23(3), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05310.x

Oketch-Rabah, H. A., Roe, A. L., Rider, C. V., Bonkovsky, H. L., Giancaspro, G. I., Navarro, V., Paine, M. F., Betz, J. M., Marles, R. J., Casper, S., Gurley, B., Jordan, S. A., He, K., Kapoor, M. P., Rao, T. P., Sherker, A. H., Fontana, R. J., Rossi, S., Vuppalanchi, R., Seeff, L. B., … Ko, R. (2020). United States Pharmacopeia (USP) comprehensive review of the hepatotoxicity of green tea extracts. Toxicology reports, 7, 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.02.008

Thanks. I drink a lot of green tea so I appreciate this article. I am not changing anything. I drink the actual tea rather than some GTE drink. The Japanese drink a ton of green tea and yet they somehow manage to outlive just about every other nationality. I am thinking green tea is not so bad. Thanks.

Once again, it sounds like people turning to "pills" to solve their problems. There are other issues related to green tea, as I recall. Plants can pick up contaminants from the soil, and it seems like the specific issue for teas may have been fluoride accumulation, although I could have that mixed up. Also, green tea and others may contain elevated levels of naturally-occurring oxalates. If oxalate intake from other foods is also high, there might be a problem.

I have green tea occasionally, and I don't drink gallons of it. It's not a magic cure, but it might help some people. One has to be wary of promotions, always, coming from people that stand to make money from increased consumption. Green tea extract without a specific indication? No way.