Getting Better Sleep

A few tips on how to improve sleep, and a few questions about your own sleep habits.

It is imperative that good health must correlate with good sleep. Following my post on the importance of sleep.

I’ll provide some evidence to a few things each of us can do to sleep better and sleep longer. Note that this information is not meant to be used as medical advice, but as food for thought for your own daily routines.

Also, it might be a little fun to provide a few polls throughout the post and see people’s responses to their overall sleep quality. These aren’t intended to be diagnostic questions, but just a few things to think about. Don’t think about answering exactly, but choose an answer that closely coincides with what you think.

Improving Sleep

If you type in search words such as “better sleep” or “sleep improvement” into a search engine you’re bound to get a ton of different articles. Here are a few examples (with links):

American Sleep Association: Ways to Improve Sleep

Sleep Foundation: Healthy Sleep Tips

Mayo Clinic: Sleep Tips: 6 steps to better sleep

Healthline: 17 Proven Tips to Sleep Better at Night

You kind of get the picture…

Although many websites are likely to have overlapping information, it can become a bit overwhelming to try to navigate the online world and see what sort of information is out there and which ones are valid1.

So it’s a bit difficult to actually provide concrete tips, but to provide some evidence found in the literature that may serve as things to keep in mind if one were to try to get better sleep.

1. Melatonin Production/Supplementation

There’s not much to say here about Melatonin that hasn’t been said anywhere else. Melatonin is a hormone produced by the pineal gland and is responsible for a host of different biochemical reactions. It’s probably one of the most widely supplemented compounds out there with Melatonin purchasing increasing every year.

Although Melatonin is well-known for its role in sleep it’s been extensively studied for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, among other things as well.

Melatonin serves as one of our body’s chemical checks on circadian rhythm. During the day melatonin production is considered to be halted due to exposure to light (especially blue light) which helps us stay alert. However, at night or during times of darkness melatonin production ramps up, causing us to feel sleepy.

For all of the hormones that aid us in sleep, Melatonin is likely to be the most important (Zisapel, N.2).

Melatonin is an important physiological sleep regulator in diurnal species including humans. The sharp increase in sleep propensity at night usually occurs 2 h after the onset of endogenous melatonin production in humans (Lavie, 1997; Zisapel, 2007); in addition, the duration of nocturnal melatonin relays night length information to the brain and various organs, including the SCN itself. […] Administration of melatonin during daytime (when it is not present endogenously) results in the induction of fatigue and sleepiness in humans (Gorfine et al., 2006). Importantly, melatonin is not sedating: in nocturnally-active animals, melatonin is associated with awake, not sleep, periods and in humans, its sleep-promoting effects become significant about 2 h after intake similar to the physiological sequence at night (Zisapel, 2007). The effects of exogenous melatonin can be best demonstrated when endogenous melatonin levels are low (e.g. during daytime or in individuals who produce insufficient amounts of melatonin) and are less recognizable when there is a sufficient rise in endogenous melatonin (Haimov et al., 1994; Kunz et al., 1999; Tordjman et al., 2013).

Considering that many of us are not getting enough sleep and reaching for Melatonin supplementation for aid, we should look to see how effective Melatonin is at improving sleep.

One systematic review/ meta-analysis Fatemeh, et. al.3 looked through thousands of articles on Melatonin supplementation, boiling the articles down to 23 RCT’s in particular. The researchers noted that Melatonin supplementation was associated with a significant improvement in sleep quality.

When looking at meta-analyses, it’s always important to remember that heterogeneity among the study methodologies (i.e. differences in demographics, supplement doses, and other factors) may bias the data. Regardless, it appears that there may be an all-around benefit for people to try supplementing with Melatonin for better sleep.

With that being said, there are a few things to consider:

One should understand why they may need to supplement with exogenous Melatonin. If every day activities and behaviors alter Melatonin production, it may be important to look at ways of modifying behavior to increase endogenous melatonin production, such as being aware of light exposure during the day and night (more on that later).

Aside from pharmaceutical Melatonin supplements, Melatonin has been found in many fruits4 such as cherries and grapes. If one were to consider other sources of Melatonin, it may be worth it to look into food sources as an alternative to pharmaceuticals.

Timing of Melatonin supplementation is important. If supplementing, seek additional advice as to the most optimal time for supplementing with Melatonin.

2. Examine Daily Light Exposure

Light exposure is possibly one of the parts of modernity that has influenced our sleep [the most]. Hormones within our bodies such as Melatonin and Serotonin derive their concentrations based on the level and type of light one is exposed to throughout the day (Ostrin, L. A.5):

Pineal melatonin synthesis and release are directly related to light exposure, and normal circadian rhythms are dependent upon exposure to regular light/dark patterns. Increased night-time melatonin promotes sleep, and decreased daytime melatonin promotes alertness. Light is the most potent Zeitgeber, or time-of-day cue, for regulating circadian activity. Light exposure has been shown to rapidly decrease the activity of AANAT and acutely suppress the production of melatonin.93–95 Melatonin undergoes a sharp rise approximately one to three hours before bed-time, which onsets in response to dim light, known as dim light melatonin onset (DLMO, Figure 3). Similarly, there is a sharp fall in melatonin in response to light onset. DLMO is considered to be a reliable, non-invasive circadian phase marker.

So it makes sense that light exposure, by virtue of their effects on Melatonin/Serotonin production, would influence our sleep.

When discussing such problems due to light exposure, the main culprit tends to be artificial light produced at times that would normally be dark, called light at night (LAN).

Artificial light from televisions, computers and hand-held electronic devices has become ubiquitous in daily life. Of importance, night-time use of electronic devices is highly prevalent, with 90 per cent of Americans reporting electronic device use in the hour before bed-time.102 Computers, cell phones and video games at night are associated with more difficulties falling asleep and less restful sleep.102 Increasingly, light bulbs and electronic displays use light emitting diode (LED) light sources, which contain a high proportion of short wavelength light near the peak of ipRGC sensitivity. Accumulating evidence suggests that LED displays are contributing to night-time melatonin suppression and sleep difficulties.103 Nighttime exposure to back-lit computer displays has been shown to attenuate melatonin.104

In a scramble to fix such a problem, many tech items now have soft light features that filter blue light at certain times. It may be beneficial to consider using such features on smartphones, laptops, and televisions if one were to use them later in the evening or at night to reduce blue light exposure and increase melatonin production.

However, many LED lights may also emit blue light which may also dampen Melatonin production. Therefore, one should consider all sources of light, and which forms of light are being emitted at night when trying to reduce light exposure.

It’s worth noting that light exposure is not entirely bad. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which is when someone experiences depressive moods during seasons of low sunlight, is usually treated through light exposure. It is thought that the lack of sunlight may affect circadian rhythms and increase Melatonin production at times we would find intrusive, and therefore the use of light therapy may reset the circadian rhythm and dampen Melatonin production for later in the day.

Adding to the “not all light is bad” argument, there is some evidence to suggest that it is not just LAN that may affect our sleep, but that lack of light during the day (LDD?-not a scientific abbreviation) may also affect our sleep cycles and the effects of LAN exposure.

One example comes from a review from Fernandez, F.6

While the “bright days” part of the circadian ledger has received some attention,14 there is no current consensus as to which—brighter days or darker nights—is more influential for shaping good sleep and circadian outcomes. Data suggest that the brighter days component might carry weight, however. First, in-lab manipulations of photohistory that vary the brightness of the indoor lighting a participant is exposed to over the subjective day (broad-spectrum fluorescent, 1 lux vs 90 lux) show that housing under dim light enhances subsequent arousal responses to a nighttime light stimulus.107

There’s not much evidence in support of light exposure benefiting sleep (mostly because there’s a general lack of such studies to begin with), however the studies that are available provide some insight.

There is some evidence to suggest that daylight sun/artificial light exposure may help to dampen the detrimental effects of LAN:

Converging lines of evidence suggest that sensitivity to LAN increases when there is a lack of preceding daytime light, raising the possibility—in turn—that the health vulnerabilities associated with LAN can be counteracted or neutralized by adequate exposure to sunlight or electric indoor lighting. This premise has the potential to make a meaningful clinical impact once there is a data-driven consensus as to how much light a person requires throughout the day (intensity and duration of exposure) to inoculate themselves against LAN’s non-visual physiological effects. Though such data are generally lacking, one dose–response study conducted by Kozaki and colleagues did maintain individuals in-lab under varying intensities of white fluorescent light (4523K) for 3 hours in the morning (09.00–12.00) before testing light-induced melatonin responses overnight (01.00–03.00).111 The design of this study was somewhat unconventional (eg, with the LAN stimulus being introduced 18 hours after the morning intervention), but in principle, the results indicate that melatonin suppression associated with LAN can be prevented with bright early-day illumination.

This all adds onto the overall benefits of daylight exposure. Sunlight exposure is associated with reductions in many diseases.

Findings at this stage suggest that sleep/circadian health problems are seeded in people when they are not exposed to the adequate amounts of daylight, thereby potentially increasing risk for other medical issues (genetic predispositions may leave some individuals particularly vulnerable to these exposure deficits146,147).

However, these effects may be confounded by the overwhelming evidence in support of Vitamin D, and so the benefits of daytime sun could be predominately due to greater Vitamin D production, which itself is known to provide better sleep as well.

Overall, the evidence supports to a need for greater understanding of our surroundings and light exposure:

If we are to get better sleep, we should be mindful of LAN exposure and the detrimental effects that light may have on Melatonin production.

Use of blue light filters may prevent the hindering of Melatonin production, and use of such products may be beneficial for sleep.

Consider how much light you are exposed to in general before bedtime as well. Do you read in bed with an LED light next to you, or are you on devices right up until you turn off the lights. Or do you continue to use your phone even when in bed?

Reducing nighttime exposure to light may not be the only way to get better sleep. Consider increasing exposure to light during the day. Although the evidence isn’t conclusive, increased light exposure during the day may help attenuate the detrimental effects of LAN. Thus it is both the timing and duration of light exposure that one should consider when trying to get better sleep.

3. Exercise

We’re definitely not getting enough exercise to begin with, and since there’s so much to be said about exercise in regards to overall health, it may be better to save most of that discussion for a future time. However, exercise does seem to have an effect on our sleep.

The effects of exercise on sleep are somewhat controversial. Although some evidence points to benefits, some may not consider exercise to be entirely beneficial. One group that generally appears to benefit from sleep are those who are elderly, or those who suffer from sleep disturbances caused by neurological deficiencies. The elderly are likely to suffer from sleep disturbances such as insomnia, whether through biochemical and physiological changes.

In one meta-analysis by Yang, et. al.7 6 studies were examined in which participants over the age of 40 were enrolled into either a moderately intense aerobic training regimen or enrolled into a high-intensity resistance training exercise. These participants had some form of sleep disturbance such as insomnia, depression, or other alterations to sleep. Overall, the studies samples suggested that exercise may improve quality of sleep:

This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive review of randomised trials examining the effects of an exercise training program on sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep complaints including insomnia, depression, and poor sleep quality. Pooled analyses of the results indicate that exercise training has a moderate beneficial effect on sleep quality, as indicated by decreases in the global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score, as well as its subdomains of subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, and sleep medication usage. Other sleep time parameters, including sleep duration, efficiency, and disturbance, were not found to improve significantly. These findings demonstrate that the participants did not sleep for a longer duration after participation in exercise training but they nevertheless perceived better sleep quality. Since poor sleep quality and total sleep time each predict adverse health outcomes in the elderly (Pollack et al 1990, Manabe et al 2000), optimal insomnia treatment should not only aim to improve quantity but also self-reported quality of sleep.

It’s important to note that some of these studies measured improvements in quality of sleep through self-reports. However, given the circumstances it probably wouldn’t be considered too concerning to include self-reports of better sleep (someone reporting better sleep may be more closely associated compared to other measures of health that may be self-reported).

Another systematic review from Kelley, G. A. & Kelley, K. S.8 looked into previous meta-analyses and found that many studies suggest that exercise leads to improved sleep outcomes. Based on these results, the researchers comment that exercise should be considered in guidelines for improving sleep:

The findings of the current review provide important information for practice. First, despite the low quality of evidence as well as lack of statistically significant results for several sleep outcomes, exercise appears to improve selective sleep outcomes, including more global measures of sleep. While no specific recommendations directed solely at sleep outcomes can be made and further research is needed, it would appear pragmatic to suggest that adherence to current and broad guidelines for exercise be recommended. These include at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity such as brisk walking or 75 minutes or more each week of vigorous-intensity activity such as jogging.51 Some combination of the two is also acceptable.51 Additionally, at least two days per week of muscle strengthening activities that exercise the major muscle groups of the body (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms) should be performed.51 However, it is important to note that these are general recommendations.51

Although the evidence points towards the benefits of exercise on sleep, it’s hard to argue that we should not be exercising more in general. Exercise is related to all sorts of clinical benefits, and so even if the evidence in favor of exercise and sleep is sparse, it should not undermine the significance of exercise as a whole.

And this is a general issue when we look for a narrow fix to problems. It shouldn’t be the one thing that fixes another, but it should be the overall health benefits provided by activities such as sleep or exercise. Exercise is necessary for overall good health, so we should be encouraged to exercise more regardless.

4. Look into Diet and Nutrition

What we put into our bodies certainly has an effect on our overall sleep. There are many things that could contribute to sleep, and so we will highlight a few compounds here. Note that many studies are not conclusive, and many citations (unless otherwise stated) will draw information from the Zhao, et. al.9 review. Not all vitamins and compounds will be examined here, so for additional compounds refer to the Zhao, et. al. review.

Caffeine

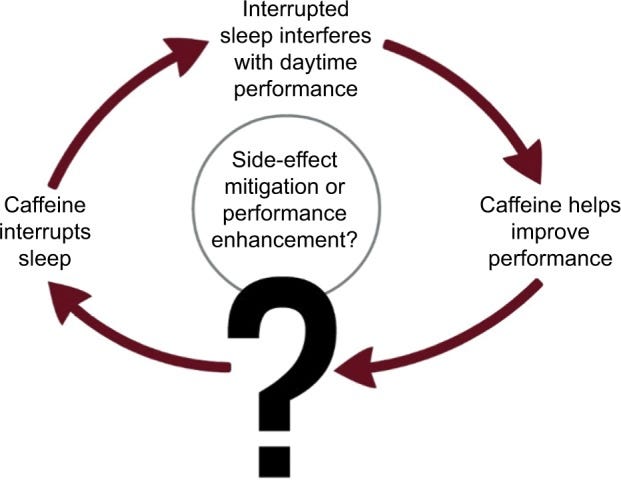

Caffeine has become pretty ubiquitous in the Western world. A night of sleep is usually driven by coffee in the morning. It’s rather ironic given the stimulant properties of coffee- good sleep probably shouldn’t require additional stimulants to get us through the day. Yet that is generally the case. Our caffeine consumption, predominately through coffee, is likely to create a paradoxical loop in which lack of sleep one day may drive us to become caffeinated, possibly altering our sleep later that night, causing us to seek out coffee the next day, and so on and so forth.

A review by O’Callaghan, et. al.10 calls this cycle a sleep “sandwich”, in which sleep is sandwiched between two periods of stimulation via coffee:

For the majority of adults in Western countries such as the United States, sandwiched between one day of caffeine consumption and the next is a period of caffeine deprivation— sleep. If caffeine consumption is not wisely regulated during the first daytime, sleep deprivation will ensue, and performance deficits will be experienced during the subsequent daytime. Caffeine consumption by day causes a reduction in 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (the main metabolite of melatonin) on the ensuing night,20 which is one of the mechanisms by which sleep is interrupted. Given that the number of Americans who sleep fewer than 6 h per night increased from 13% to 20% from 1999 to 2009, widespread caffeine consumption may well have broad societal implications.1,21

So not only are we a society lacking sleep, we’re also a society that supplements with stimulants via caffeine. This complicates many studies. Is coffee the cause, or the result of lack of sleep?

The O’Callaghan, et. al. review looks into several of these studies, all of which generally complicate the association of caffeine to sleep, including studies on caffeine withdrawal.

Therefore, more important to the actual effects of coffee, we should understand why we caffeinate ourselves to begin with. It’s a matter of the chicken and the egg scenario (sleep and the coffee), and figuring out which came first and which caused the other.

On another note, Robin Whittle of Nutrition Matters has left an extensive comment in the prior post in regards to caffeine intake. I haven’t checked most of the information, but I’ll provide it for some additional remarks on caffeine. Please take a look at his comment for more context and additional information:

Caffeine is a terrible sleep disruptor, not just through its immediate effects a few hours after consuming it. Caffeine drives Restless Legs Syndrome / Periodic Limb Movement Disorder (RLS / PLMD, which are separate diagnostic criteria - sensation and movement - for the one underlying disorder). I didn't know this when I wrote a Letter about this https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jcr.2014.0024 . I should make an updated version of this publicly available. There is an article from about 15 years ago I can't find right now which reports on people with RLS/PLMD whose problems went away after they stopped using caffeine.

It is my impression that caffeine withdrawal drives RLS/PLMD - the effects of consuming caffeine more than 3 hours or so beforehand. A small amount of caffeine may quell these withdrawal effects and so reduce RLS/PLMD for a while.

Chocolate contains caffeine, theobromine (which very similar to caffeine, and from which coffee plants make their caffeine) and other substances. Unfortunately there is something in chocolate which drives RLS/PLMD immediately and in the ~~3 to 6 hours which follow.

Coffee, but not tea or chocolate, contains opioid receptor antagonists. These surely directly disrupt sleep by reducing the level of background opioid receptor activation caused by endogenous opioids. See the research cited at: https://aminotheory.com/coffee/ . Opioid receptor antagonists also directly drive RLS/PLMD.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Drawing from the Zhao, et. al. review there are some suggestions that supplementation with Omega-3 may aid in sleep:

Studies have suggested that diet deficient in omega-3 PUFA disturbed nocturnal sleep though affecting the melatonin rhythm and circadian clock functions [48]. There is also a positive relation between omega-3 fatty acid composition in gluteal adipose tissue and sleep wellness including slow wave sleep and rapid eye movement sleep among obese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome [49]. A study of healthy children has reported that higher blood DHA level is associated with significantly improved sleep wellness [50]. In their subsequent randomized controlled trial (RCT) of DHA supplementation (with 600 mg/day for 16 weeks), significant group differences were observed including sleep duration increased by 58 min and fewer and shorter night-wakings in the treatment group versus the placebo group [50]. Other than children, the effect of DHA on sleep was also reported in adolescents, as higher plasma DHA was associated with earlier sleep timing and longer weekend sleep [51].

However, there are some conflicting evidence as well. Once again, the use of Omega-3 such as fish oils should be looked at through the overall effects of Omega-3 on health, as Omega-3 fatty acids are considered to be vital for cardiovascular health.

Tryptophan

Turkey is generally synonymized with sleepiness, and such associations are generally blamed on the tryptophan content found in turkey. Tryptophan is a substrate of serotonin, and so consumption of tryptophan may be associated with sleepiness:

Tryptophan is the substrate for serotonin which has been intensively studied on its role on sleep for many decades [20]. Although the role of serotonin on sleep has been under debate, there is a general agreement that serotonin is a major sleep mediator which first increases wakefulness but then increases NREM sleep [20]. Considering the role of serotonin, it has been indicated that supplementation of tryptophan (1 g or more) produces an increase in subjective sleepiness and a decreased time to sleep especially in subjects with mild insomnia [62]. A random double-blind experiment on healthy adults suggested that tryptophan consistently reduced sleep latency which is associated with blood levels [63]. Recently, a Japanese study of younger aged population concluded that tryptophan ingested during breakfast is required for children to keep a morning-type diurnal rhythm and maintain high quality sleep [64]; however, this study did not involve supplementation of tryptophan, instead they calculated the tryptophan-index based on food they consume.

Similar remarks were made in a review from Binks, et. al.11 in which Tryptophan deficiency has been associated with sleep impairment.

Vitamin D

We’ll lastly take a look at Vitamin D, which is another one of those vitamins that doesn’t need much explanation. It’s been talked about extensively, is something that is generally gained through sunlight exposure, and so overall it should make sense that Vitamin D is associated with better sleep:

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin which is crucial for the absorption of calcium and many other biological effects. The most important vitamin D3 and D2 can both be synthesized by the body in the presence of sunshine or obtained from the diet. Fatty fish is a major source of dietary vitamin D. Multiple studies have studied the role of vitamin D on sleep. A meta-analysis including 9 studies (6 cross-sectional, 2 case-control, and 1 cohort studies) aimed at clarifying the association between vitamin D and sleep disorder risk [74]. Overall, the study concluded that vitamin D deficiency is associated with a higher risk of sleep disorders including poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, and sleepiness [74]. When examining each individual studies, most studies indeed suggested positive correlation of vitamin D intake and sleep quality. Moreover, there is an association between serum vitamin D levels and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome [75]. The mechanism regarding the role of vitamin D in sleep is yet to be confirmed, possibly related with inflammation and oxidative stress [75].

Considering that many people are already likely to suffer from Vitamin D deficiency, this is another one of those situations in which Vitamin D may be looked at for its overall health benefits, and not how it influences sleep alone.

Taking Control of your Sleep

This review hasn’t been exhaustive, but hopefully the information here can help you to examine all of the factors that may influence our quality of sleep. There are some things that haven’t been covered, including the effects of stress.

When going to bed tonight, consider how your behaviors and routines may affect your quality of sleep. Be mindful of what foods you eat, your dependency on caffeine, or if you may be using devices far later into the night than you should.

Sleep is important to our overall health, and in times of uncertainty always consider the small things you can do to make yourself and your body more antifragile.

Also, just a few more questions about sleep.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Although the Healthline website has links to PubMed, I doubt that all 100 articles linked were read through. Be careful in assuming that the information provided is well-cited for some websites.

Zisapel, N. (2018) New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175: 3190– 3199. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14116.

Fatemeh, G., Sajjad, M., Niloufar, R., Neda, S., Leila, S., & Khadijeh, M. (2022). Effect of melatonin supplementation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of neurology, 269(1), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10381-w

Interestingly enough, both Melatonin and Serotonin are utilized by plants as a form of stimuli. In fact, Melatonin is deeply associated with many plant hormones and influences gene expression and plant immunity.

M B Arnao, J Hernández-Ruiz, Melatonin and its relationship to plant hormones, Annals of Botany, Volume 121, Issue 2, 23 January 2018, Pages 195–207, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcx114

Ostrin L. A. (2019). Ocular and systemic melatonin and the influence of light exposure. Clinical & experimental optometry, 102(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12824

Fernandez F. X. (2022). Current Insights into Optimal Lighting for Promoting Sleep and Circadian Health: Brighter Days and the Importance of Sunlight in the Built Environment. Nature and science of sleep, 14, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S251712

Yang, P. Y., Ho, K. H., Chen, H. C., & Chien, M. Y. (2012). Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy, 58(3), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70106-6

Kelley, G. A., & Kelley, K. S. (2017). Exercise and sleep: a systematic review of previous meta-analyses. Journal of evidence-based medicine, 10(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12236

Zhao, M., Tuo, H., Wang, S., & Zhao, L. (2020). The Effects of Dietary Nutrition on Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Mediators of inflammation, 2020, 3142874. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3142874

O'Callaghan, F., Muurlink, O., & Reid, N. (2018). Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning. Risk management and healthcare policy, 11, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S156404

Binks, H., E Vincent, G., Gupta, C., Irwin, C., & Khalesi, S. (2020). Effects of Diet on Sleep: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 12(4), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12040936

Thank you Modern Discontent for a thorough view.

Melatonin:

Melatonin is a powerful antioxidant. Not only does it manage your sleep phase, but it protects from cancer cells wandering around. Been taking it for 35 years - started at 3mg/night, now 10mg/night. But as you get older, your pineal gland does fade. The Pineal Gland is the Third Eye of indigenous/spiritual people. Cannot recommend enough!

Daily Light Exposure:

Peoplekind were designed to wake at dawn, sleep at dark. You wake naturally with the light, and sleep naturally with the sunset. This the Circadian Rhythm. Shocked that people sleep less than 6 hours/night. Our modern world (sounds archaic, we are probably neo-modern now) offers off-hours work, a diversion from the melatonic sun-clock, farm animals go by the sunrise.set, imposes a very false set of standards. When I was growing up, TV came on the air 4pm, off air 11.20pm. I wish that was still the benchmark.

Exercise (diet & nutrition)

See above Daily Light Exposure. You are supposed to work/exercise your body/be alive during daylight hours.

Caffeine:

Use with caution. It is a good antioxidant but yymv. Myself,can't drink coffee after 9am or it interferes with Melatonin, Daily Light. Exposure.

Omega 3:

Originally from saltwater fish and grass fed cattle, it is becoming a supplement, which is ridiculous. Go for Atlantic sardines - only true good source. Your body needs this to metabolize a bunch of important legacy stuff.

Tryptophan:

I stay away from turkey meat. I keep my dogs away too. I don't want to be sedated. Scary how big the turkey has grown, As a child, we would go to the turkey farm and pick a bird. All running around chirpy, oblivious.

Vit D

Oyez, oyez: Free antioxidants! Free antioxidants! Nobody cares. They rely on pharma now. Centuries, if not millennia of healing plant protocols available. My pharmacist brother could not understand why I never had covid (after all, they had the jabs and caught it, regardless.) Maybe I had but not realized? Nope. Antibody and T Cell tests show I have never, and will likely never. Because if you boost your immune system, sleep well, forgive and don't forget - is all you need.

MD I hate surveys. I did it anyway, but won't again. Thank you and STAY STRONG.

I also drink a lot of coffee, and it does not affect my sleep. I've always been a heavy coffee drinker.

Since Covid, I now add things like turmeric, ashwaganda, astralaga, and various teas to my coffee, so as not to cause my stress about should I or should I not quit. I just get things in my body the easiest way possible.

Now, exercise is a problem for me now. Since I got the J&J shot in March of 2021, I have been anxious about clotting. And, with all the sudden deaths nowadays, especially after exercise, I'm warier about strenuous exercise. I actually research and found out that strenuous exercise is not recommended when you are ill. I consider exposure to the virus (which is unavoidable now), as a potential illness, the immune system is working on. I know that constant exposure to the virus being introduced into your body (high-infectious pressure), is not a good thing. It is for this reason that I do moderate movements throughout the day to get in "exercise".