Elderberry- nature's antiviral?

This commonly found berry is growing in popularity. Is it a good choice for cold/flu season?

This was something I’ve intended to work on all month but was caught up with work. The initial intention came from me getting sick right after Christmas with a 24-hour bug, and during that time I only ate rice porridge and drank elderberry juice. It was also one time in forever that my body decided to entertain me in a game of upchucking, which isn’t really fun when the stuff coming out of your body is reddish/purple... Was it due to the infection? The elderberry juice and its purgative effects? Not sure, but let’s just say that inspiration can come from very weird places. Unfortunately, the window may have passed for this post as we seem to have moved on from everyone getting sick (and out of elderberry season), but the information here may be nonetheless something that may interest some readers.

Also, note that this article is not original as several writers on Substack have covered elderberry in the past as well, including Weedom who also includes a recipe for elderberry oxymel from Lisa Brunette. Just note that there is likely to be overlap in some of the information covered.

In following another period of “everyone seems to be getting sick” I thought it would be interesting to cover something you likely have come across either online or on drug store shelves, and that is the illustrious elderberry. You’ve likely heard of this berry’s many benefits and has been considered as a possible treatment for colds and flus, hence why many pharmacy shelves appear to be inundated with elderberry-based products.

History and Background

The elderberry is found rather commonly in both Europe and North America. The species found within Europe is the Sambucus nigra, with the species found within North America being the Sambucus canadensis. It’s likely that the close relationship between these two plants helped to make the plant easily recognizable to colonizers. They are, after all, 2 of several elderberry species that fall under the Sambucus genus.

The name appears to be of Anglo-Saxon origin, derived from the word aeld meaning “fire” or “burn”, and appears to be related to the suggestion that the stems of the elderberry plant were used blow onto fire and kindling to help keep them lit. The name may also be derived from old English due to the word eldre which means “tree”.

The history of this plant’s medicinal uses appears to expand several centuries, and has been noted by even individuals such as Hippocrates for its beneficial uses (from JSTOR Daily):

The history of humankind’s fondness for Sambucus is long. Hippocrates referred to the elder plant as his “medicine chest” in 400 BC for its breadth of applications. His observation has echoed through the centuries across European and Indigenous American healing traditions. One English reference text, The family herbal, first published in 1754 and held by Dumbarton Oaks Library, remarks that the “inner bark” of the elder served as a “strong purge…known to cure dropsies [a term thought to refer to edema or congestive heart failure] when taken in time.” According to this text, elderflowers could be boiled in lard to produce a cooling ointment, while the berries could be used to make wine or “boiled down with a little sugar” to produce “the famous rob of elder, good in colds and sore throats.”

There were several other uses, as noted in an article from Penn State Extension:

In ancient times, it was considered a tree of healing and prosperity. In those two historic texts, all parts of the plant were mentioned as useful. However, we now know that the leaves, twigs, and roots are toxic when consumed. In Europe, elderberry was revered for its use in the home. It was also used to ward off evil. Elderberry was planted near the house as protection from attackers and harmful spirits. Care was taken when cutting down elderberry by saying a blessing lest a witch spring from its branches.

Use of elderberry in the Americas dates as far back as 1300-1000 BCE. All parts of the plant were used by indigenous peoples whether for food, medicine, or enjoyment. Since the wood of the elderberry can be hollowed, given its soft pith, it was used to make flute-like instruments and percussion sticks. It was also used to make a salve for cuts, abrasions, and burns. The elderflower was made into an infusion (tea) to treat fever and colic in babies. The berries were used to treat coughs and colds.

And evidence suggests that the plant may have been used for its possible purgative effects (referring to the JSTOR Daily article):

In contrast to The family herbal, elderberry’s utility to medical practice in the King’s American dispensatory is expressed in terms of its chemical makeup rather than through clinical observation or cultural tradition. As it notes, elder is a “purgative” force useful in reducing swelling by encouraging secretion from fluid-filled tissues as well as in “febrile diseases,” including scarlet fever due to its “diuretic properties” and its levels of “malic acid, citric acid, resin, fat, sugar, gum, and tannin.”

“Purgative” and “diuretic” are interesting words used here, as evidence has found that many parts of the elderberry plant, including the stem, flowers, unripe berries, and especially the leaves contain compounds known as cyanogenic glycosides, or sugars which bear a cyano/nitrile functional group. Cyanogenic glycosides are compounds which release cyanide through metabolism, and as such can cause harm if consumed at high doses or over long periods. Most notably two cyanogenic glycosides have been found within the elderberry plant named Sambunigrin and Prunasin, respectively:

Unripen elderberries may also contain Zierin and Holocalin, which are cyanogenic glycosides bearing meta-hydroxyl groups as part of the aromatic ring:

These compounds can be metabolized via enzymes or readily hydrolyzed, resulting in a release of free hydrogen cyanide which can induce toxic effects at adequate doses.1

Of note, several symptoms of cyanide poisoning include nausea, headaches, chest pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and altered heart rate and blood pressure.

Given the historical use of all parts of the elderberry plant, and the intended use for these purgative/diuretic effects, it’s curious if some of these effects were due to ingestion of these cyanogenic glycosides or due to other compounds derived from the elderberry itself. It’s worth noting that elderberry products appear to also produce diuretic effects while not bearing the toxic glycosides.

For additional context, in one study where several genotypes of American Elderberry were assessed (Ozark, York, Wyldewood, Ocoee, and Bob Gordon in particular) for cyanogen among the various plant parts, results noted a relatively higher level of cyanogenic glycosides within the stems and green/unripe berries among these AE genotypes2:

And interestingly enough, agricultural factors such as the altitude at which plants are grown can also increase the level of cyanogenic glycosides, suggesting that the methods in which the elderberry plant are grown may attenuate/exacerbate the levels of toxic compounds.

In contrast, most commercially available elderberry juice tends to show no quantifiable level of cyanogenic glycosides. This is likely due to the separating of the berries from the seeds, as well heating of the elderberry as heat, fermentation, and other processing methods appear to help remove a large majority of the cyanide-bearing compounds, like the historical processing of cassava which also aided in removal of harmful hydrogen glycosides prior to consumption.

Because most people source their elderberry through commercial products the rates of cyanide poisoning derived from wild elderberry appears rare. However, it’s worth noting that a few years ago a Columbia University professor possibly poisoned herself through using elderberry tincture, although the story as reported by New York Post lacks a lot of context as the professor never confirmed her cyanide toxicity through testing, and also attempted to treat her possible poisoning with other homeopathic remedies.

In any case, care should be taken to be diligent when sourcing your own elderberries by avoiding all parts of the plant aside from ripe (dark) berries, although I doubt most people would be hungry for elderberry stems anyways.

Now, as to why plants may produce such toxic agents the obvious answer appears to point towards their use as defense against predation by herbivores. This may partially explain why levels of cyanogenic glycoside greatly vary among different parts of the plant and may explain the level of cyanogenic glycosides within younger elderberry fruits relative to older ones. Relatively lower levels of these toxic compounds in berries may also highlight a focus for herbivores to consume the berries to help spread seeds (speculation on my part).

Regardless, the historical context in which elderberry was used serves as a template for this berry’s many possible health benefits. Although some thought should be put towards the actual veracity of these historical claims (and whether cyanide-related toxicity may be partially responsible), a growing body of evidence has elucidated many compounds that seem to be critical to our well-being.

Bioactive Compounds

Like many other fruit-bearing plants many of the allegedly beneficial components of elderberry stem from the polyphenols found within these berries, which should not come as a surprise given their purplish dark color.3

For instance, elderberry is rich with anthocyanins, with Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside being one of the most dominant forms of anthocyanin.

Elderberry also contains several flavanol components, including several quercetin conjugates. Phenolic acids are also common as well, and all these compounds together appear to contribute to the many health benefits derived from elderberry.

A simplified diagram highlighting all these compounds can be seen below:

As has been discussed many times in past articles the combination of anthocyanins and flavonoids are likely responsible for the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of elderberry.

Regarding elderberry as a robust antioxidant agent the mechanisms of antioxidation appear to relate to both free radical scavenging as well as modulation of oxidation pathways.

Given the scope of this review not all discrete mechanisms can be detailed, and instead here are a few articles which may interest readers if they would like further information:

Advanced research on the antioxidant and health benefit of elderberry (Sambucus nigra) in food – a review4- (Sidor, A. & Gramza-Michałowska, A.)

Elderberry Extracts: Characterization of the Polyphenolic Chemical Composition, Quality Consistency, Safety, Adulteration, and Attenuation of Oxidative Stress- and Inflammation-Induced Health Disorders5- (Osman, et al.)

Elderberries—A Source of Bioactive Compounds with Antiviral Action6- (Mocanu, M. L., & Amariei, S.)

Bioactive properties of Sambucus nigra L. as a functional ingredient for food and pharmaceutical industry7- (Młynarczyk, et al.)

In addition to these antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties elderberry has also garnered attention as an anticancer agent as well.

Bear in mind that these claims should be met with some hesitancy, especially as we become more health-conscious and begin to look for anything that may claim to aid in our overall health. For instance, there’s a growing body of research suggesting that the field of antioxidant research may be more complex than is being reported, mainly due to what’s called the antioxidant paradox8 in which preclinical studies utilizing antioxidants may show extremely positive results that don’t appear to translate over into human clinical trials. This suggests that the idea of antioxidation may be more complicated than it is made out to be. This should also be paired with the fact that free radicals themselves serve as vital signaling molecules within our bodies, again further complicating the role of antioxidants. More will be covered in a future to be determined article regarding the antioxidant paradox, but all of this is something worth considering.

Antiviral Actions of Elderberry

Now, what’s interesting is that elderberry appears to show some degree of activity in vitro. Most of the research regarding these antiviral properties appear to relate to the ability of several elderberry-derived polyphenols to directly bind to viruses, rendering them incapable of binding to host receptors and entering host cells.

The review from Mocanu, M. L., & Amariei, S. summarizes some of these findings in the following way:

The effects of S. nigra fruits against influenza have been the most intensively studied, but research in this field is usually considered only level B, as substantial research is still needed in this field, few mechanisms being explained in terms of inhibition of influenza symptoms [7]. (Assessment level B is in accordance with the validated evidence-based classification standard, equivalent to “You can apply this treatment”: level 2 or 3 studies or level 1 extrapolations).

Sambucus nigra flavonoids are able to prevent the virus from entering host cells, preventing the pathogenesis of the flu. Moreover, agglutination of Sambucus nigra flavonoids stops influenza infection by competitively inhibiting the virus and subsequently by endocytosis [37].

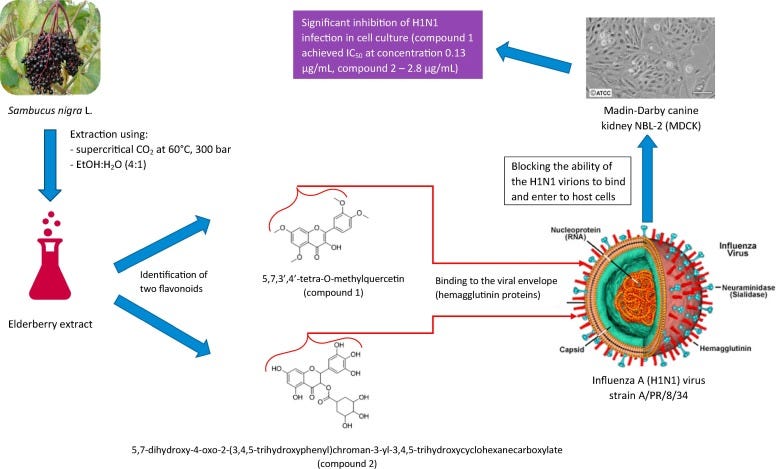

Another study showed that 5,7,30,40-tetra-O-methylquercetin and 5,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)chroman3-yl-3,4,5-trihydroxycyclohexanecarboxylate have an effect on influenza virus. It was shown that they inhibit H1N1 infection in vitro by binding to H1N1 virions, blocking host cell entry and/or recognition [63].

S. nigra fruits appear to prevent influenza infection by competitively inhibiting the influenza virus that binds to host cells to begin its pathogenesis [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73].

Interestingly, the molecule 3′,4′,5,7-Tetra-O-methylquercetin mentioned above (trust me, it’s in there somewhere…9) was featured as one of ACS’s molecules of the week:

What’s curious is if other plants produce these flavonoids, as it would provide evidence that these antiviral molecules may be more commonly found than in just elderberry alone.

But fortunately for the elderberry it appears that these two flavonoids have only been characterized within elderberries, with 3′,4′,5,7-Tetra-O-methylquercetin possibly being found in two other plants. This at least provides evidence towards elderberry possibly having a unique antiviral mechanism that may not be found in other plants, at least when it comes to targeting H1N1.10

In addition, it’s worth noting that several in vitro studies have suggested an antibacterial role of elderberry extracts, however additional studies have not been conducted to see if this effect translates over to humans.

Human Trials

When it comes to trials testing elderberry on humans evidence tends to be rather scant. However, the information available appears to suggest that elderberry supplementation may help to reduce cold symptom duration and reduce illness severity, although these studies tend to be plagued by very small sample sizes and low quality studies likely affected by several biases.11

Keep in mind that more research would be needed to see if any of these in vitro and ex vivo studies translate well into humans.

Is Elderberry a cytokine storm brewer?

With the onset of the COVID pandemic people turned to anything possible to provide a benefit, including elderberry, leading to an increasing public interest into elderberry supplements.

However, reports also came out warning not to take elderberry for fear that it could exacerbate cytokine release, as noted in a Healthline article from 2021. This would be rather problematic given the initial comments on cytokine storms relating to COVID.

Some of the evidence appears to be derived from two studies12,13 in particular in which it was noted that exposure of human-derived monocytes or MDCK Cells to elderberry appears to increase IL-6, IL-8, and TNF levels.

Note that this effect was considered to be pertinent to elderberry’s antiviral properties, as it was suggested that this cytokine production may help sensitive the immune system towards a quicker response to initial infection and therefore may actually be beneficial/protective.

That being said, several other studies, including a recent study using human participants14 provided an elderberry infusion for 4 weeks noted a reduction in inflammatory cytokines, meaning that the actual role of cytokines production from elderberry is unclear. This is a reminder that we are comprised of complex systems which may not be captured in single studies. In this case, it appears that the overall effects of elderberry may be more in line with anti-inflammation similar to many other polyphenol-rich plants.

But even if elderberry did increase cytokine levels, it’s obvious now that the worries over cytokine storms related to COVID were heavily overblown. It’d be hard to argue that a combination of elderberry during COVID would lead to worse symptoms and illness, and it’s strange why such concerns were spread around in the first place.

In summary

For a summary and tl;dr:

Elderberry is a rather commonly found plant used by various cultures for centuries. Historical accounts note its use for respiratory illnesses, fevers, and was utilized as a purgative. Recent evidence has noted possible anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antioxidative capabilities related to elderberry.

Most of the beneficial properties of elderberry have been associated with their high polyphenol content. On one hand, many fruits and vegetables are rich in polyphenols and so this effects may not be specific to elderberry. On the other hand, two flavonoids found within elderberry have been found to interact with virions and produce an antiviral effect, suggesting a possibly unique pharmacological benefit not found with other plants.

Many parts of the plant contain cyanogenic glycosides which can release hydrogen cyanide when metabolized, and so care should be taken when considering harvesting your own elderberries. In many cases treatment of elderberries with heat or fermentation can help to remove many of these toxic glycosides. Take care to research different methods if sourcing your own elderberries. Be aware that most elderberry products in store tend to have undetectable or very low levels of these glycosides.

Keep in mind that heterogeneity across studies means that the clinical evidence of elderberry is rather mixed. Dosing, duration of treatment, and other factors may explain some of the effects seen from elderberry. More importantly, keep in mind that evidence from in vitro and ex vivo studies may not reflect actual benefits in humans (the antioxidant paradox).

The toxic effects of elderberry appear to be minimal (if treated properly to remove cyanogenic glycosides). Warnings of possible cytokine exacerbations, especially within the context of COVID, also appear exaggerated.

Overall, elderberry appears relatively safe for most people, and therefore may be something worth investigating for those who would like a non-pharmaceutical component to add their lives.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Cyanogenic Glycosides: Synthesis, Physiology, and Phenotypic Plasticity

Roslyn M. Gleadow and Birger Lindberg Møller

Annual Review of Plant Biology201465:1,155-185

Appenteng, M. K., Krueger, R., Johnson, M. C., Ingold, H., Bell, R., Thomas, A. L., & Greenlief, C. M. (2021). Cyanogenic Glycoside Analysis in American Elderberry. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(5), 1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26051384

As noted in prior articles anthocyanins are what give many plants their blue, purplish, and dark red color. Along with being used as a medicinal agent elderberries were also used as a coloring agent, becoming a natural dye source being used for various materials such as clothes and foods due to their anthocyanin content.

Andrzej Sidor, Anna Gramza-Michałowska. Advanced research on the antioxidant and health benefit of elderberry (Sambucus nigra) in food – a review. Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 18, Part B, 2015, Pages 941-958, ISSN 1756-4646, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2014.07.012 .

Osman, A. G., Avula, B., Katragunta, K., Ali, Z., Chittiboyina, A. G., & Khan, I. A. (2023). Elderberry Extracts: Characterization of the Polyphenolic Chemical Composition, Quality Consistency, Safety, Adulteration, and Attenuation of Oxidative Stress- and Inflammation-Induced Health Disorders. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 28(7), 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28073148

Mocanu, M. L., & Amariei, S. (2022). Elderberries-A Source of Bioactive Compounds with Antiviral Action. Plants (Basel, Switzerland), 11(6), 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060740

Młynarczyk, K., Walkowiak-Tomczak, D., & Łysiak, G. P. (2018). Bioactive properties of Sambucus nigra L. as a functional ingredient for food and pharmaceutical industry. Journal of functional foods, 40, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.025

Halliwell B. (2013). The antioxidant paradox: less paradoxical now?. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 75(3), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04272.x

If you’re curious, it’s the molecule labeled as “5,7,30,40-tetra-O-methylquercetin” within the excerpt from Mocanu, M. L., & Amariei, S.This just shows how molecules can be named various ways. Nomenclatures can also become more confusing the more complex a molecule becomes. As of now, the naming provided by ACS is the clearest as it provides information on where the O-methyl groups reside on the molecule. As a hint for those interested, the numbering is divided into two separate ring structures, with the ` notation noting a ring structure with second priority. Can you figure out the numbering system for this molecule?

Młynarczyk, K., Walkowiak-Tomczak, D., & Łysiak, G. P. (2018). Bioactive properties of Sambucus nigra L. as a functional ingredient for food and pharmaceutical industry. Journal of functional foods, 40, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.025

Wieland, L. S., Piechotta, V., Feinberg, T., Ludeman, E., Hutton, B., Kanji, S., Seely, D., & Garritty, C. (2021). Elderberry for prevention and treatment of viral respiratory illnesses: a systematic review. BMC complementary medicine and therapies, 21(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03283-5

Barak, V., Birkenfeld, S., Halperin, T., & Kalickman, I. (2002). The effect of herbal remedies on the production of human inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ, 4(11 Suppl), 919–922.

Golnoosh Torabian, Peter Valtchev, Qayyum Adil, Fariba Dehghani, Anti-influenza activity of elderberry (Sambucus nigra), Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 54, 2019, Pages 353-360,ISSN 1756-4646, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2019.01.031.

Kiselova-Kaneva, Y., Nashar, M., Roussev, B., Salim, A., Hristova, M., Olczyk, P., Komosinska-Vassev, K., Dincheva, I., Badjakov, I., Galunska, B., & Ivanova, D. (2023). Sambucus ebulus (Elderberry) Fruits Modulate Inflammation and Complement System Activity in Humans. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(10), 8714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24108714

It's always elderberry season 😎.

(So nasty if you hurl something so colorful that might even stain the "throne", and memorable for sure. I have sympathy, and a relatable 🤢 red pepper story.)

I noticed 3',4',5,7 tetra-methyl-O-quercetin which got the 30,40 numbering in the Mocanu article, had the regular ACS numbering in the article that Mocanu referenced. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19682714/

Chemical nomenclature drives me nutz. I stored an article on how those plant flavanoids are numbered in IUPAC-land. https://iupac.qmul.ac.uk/flavonoid/index.html#Flv361 It's fairly systematic, I guess.

So glad you included the cytokine storm discussion. Even before COVID people had been somewhat terrorized by the Spanish flu story in which many deaths were later blamed on cytokine storm. In herbalism people were being talked down from using echinacea and elderberry for flu.

Seems to me that on balance these plants are immune modulatory rather than immune stimulants. They can enhance some immune functions and chemotaxis, and suppress others.

I have an elderberry OTC cough and cold formula I keep on hand at the start of winter, when taken just as sxs begin, it always nip it in the bud. thank you for this well thought out article. I hope the job is going well!