Beware those leaves of three

Some notes on poison ivy, what the "poison" is, and if the rashes are contagious.

I really couldn’t come up with an original title…

Growing up I was known as one of those kids who couldn’t help but get a poison ivy- related rash every summer.

Back then, I would always go out and venture into the woods with friends, and didn’t pay no mind to nefarious “leaves of 3” plants, but of course I would have to pay for it with the itchy blisters. Even now, there are some slight scarring on my hands from my hears of blistering and scratching (or maybe I just have bad skin).

In any case, as more people begin to venture out, it may be worth taking note of these plants, lest you spend your summer days burning and itching!

A family (well, genus) to itch over

Poison ivy, poison, oak, poison sumac, and other similar plants belong to the genus Toxicodendron, which is part of the Anacardiaceae, or cashew, family of plants.

This genus also includes the Chinese lacquer tree1 (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), whose dark sap has been used for centuries by those in Asia to provide a glossy finish to many pieces of furniture, musical instruments, bowls, and other decorative items.

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is native to eastern parts of North America, and appeared to have crossed into the Asian continent some time in the recent past.

Poison ivy, in a similar vein as poison oak (T. diversilobum) and poison sumac (T. vernix), derive their name from looking similar in nature to other non-toxic plants. Supposedly, in 1624 explorer John Smith detailed the plant in his early writings and made such notes, as remarked on in an article from the Science History Museum:

In 1624 explorer John Smith published the first written account of poison ivy, basing it on an unpublished manuscript by Nathaniel Butler, who learned about the plant while governor of Bermuda. Smith’s brief description neatly summarizes the plant’s appearance and irritant effects: “The poisoned weed is much in shape like our English Ivy, but being but touched, causeth rednesse, itching, and lastly blisters.”

If true, this is likely where the word “poison” became affixed to this ivy simulacrum. Although the rash experienced by John Smith appeared mild in nature, the name nonetheless seemed to have stuck, and so we now have poison ivy.

Poison oak is found generally within the coastal regions of the North America, including parts of Mexico and Canada. Poison sumac is found in the eastern part of the continent, and generally around marshy, swampy areas.2

The old saying “if leaves of three, let it be”, serves as a cautionary tale to watch out for poison ivy and poison oak, as these plants present with leaves organized into triplets.

The Cleveland Clinic also provides their own quick reference to help identify these 3 plants as well:

Itchy Urushiol

The itchy culprit in question lies in an oily group of compounds called Urushiol. Urushiol was named by Japanese chemist Rikō Majima, who was the first to isolate and characterize the compound (prior to this scientists wrongly assumed the irritant was a carbohydrate). The name appears to be derived from the Japanese word urushi, which aptly refers to Japanese lacquer.

Urushiol is not one compound in particular, but several compounds differentiated by the length and position/number of double bonds on the compound’s carbon chain.

In general, the two main groups found on Urushiol include the catechol, which is a ring bearing two alcohol groups similar to catecholamines, as well as the carbon side chain.

The carbon chain of Urushiol appear to either be 15 or 17 carbons in length. Due to this tail, Urushiol is imparted with an extremely lipophilic characteristic. And it’s this high lipophilicity that allows Urushiol to cause rashes, as Urushiol can readily be absorbed by the skin and activate a response.

All parts of poison ivy, oak, and sumac contain urushiol, including the leaves, stems, and roots. Even touching the leaves may allow for Urushiol absorption, especially if the plants release their oily contents.

Are allergies contagious?

Now, growing up it was the norm for kids to screech that poison ivy is contagious. I guess those kids could have used some other excuse to not play with me, but this raises a rather interesting question of whether the rashes produced by exposure to Urushiol are themselves contagious.

Interestingly, this sort of question can be followed by this question in particular: are allergies contagious? Because the rashes produced by Urushiol are, in fact, an allergic response.

The rashes and blisters caused by Urishiol are caused by an allergic immune response, in which Urishiol gets broken down into metabolites and presented by Langerhan cells within the epidermis. These Langerhan cells act as antigen-presenting cells, which can then take these Urisihol metabolites to lymph nodes and present them to corresponding T-cells, leading to clonal expansion and the allergic response that leads to rash formation, as the immune system is made aware of these foreign substances and target them.

Further elaboration can be found in a review from Lofgran T, & Mahabal GD.3:

Sensitization and reexposure are mediated by a type IV cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction.[12][13][14] Langerhans cells, or antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and other acute inflammatory mediators are activated, initiating a local response. APCs break down urushiol into antigens, which either combine with major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) or are exposed on the surface of APCs. Transit of Langerhans cells to lymph nodes results in the presentation of the MHC II/antigen complex or free surface antigens to T cell receptors on CD8+ T cells via MHC II or through MHC I on CD4+ T cells, respectively. Clonal expansion then occurs, and subsequent exposure and recognition of antigens by T cells result in repeat allergic dermatitis.

Thus, exposure to Toxicodendrons follows the same sequence of events as other allergic reactions or adaptive immune responses, including a sensitization period as well as a quick memory response. The sensitization period may take days to occur, whereas any reexposure may lead to dermatitis (skin inflammation) and rash formation within a matter of hours.

This also answers the question of whether poison ivy is contagious. In essence, contact with Urushiol may allow an allergic reaction to occur, and so one would need to avoid exposure to another individual doused in Urishiol (this also includes dogs who may like to wander around in shrubs, and may explain why some animals don’t appear to respond to Toxidendrons in the same ways humans do).

However, as an allergen there are those who many not produce an immune response to Urushiol and its metabolites, and thus would not be affected by exposure.

In short, the skin rashes themselves should not be contagious and should not leave room for immediate ostracization. However, Urushiol is known to have a rather long half-life, and so any clothes or gardening tools that may come into contact with these plants may be contaminated with Urushiol for months, and even possibly years.

It’s important to remove all contaminated clothing and thoroughly wash exposed skin and clothing in order to remove any possible Urushiol.

Can poison ivy make you allergic to mangoes?

So, this header may seem like clickbait at first. I mean, how exactly can poison ivy make you allergic to mangoes?

Well, apparently there is some evidence of this occurring, with several reports in the literature of people experiencing what’s called mango dermatitis who have had past exposure to Urishiol in some form.

For instance, a report from 20054 noted 17 Americans engaged in a mango-picking activity in Israel who began experiencing various degrees of rashes. These American patients had prior history of direct exposure to poison ivy or poison oak. In those who had minor rashes, they reported not having known prior exposure to these plants, but appear to have lived in areas where these plants were widespread.

A more recent case report5 noted a 41-year old man who presented to the ER with severely itchy rashes which spread throughout the body.

In his reporting, he mentioned only being exposed to poison ivy 2 years prior. However, further investigation noted that he and his wife ate mangoes days prior to the emergence of the rashes, which included the handling of the mango peel:

The patient’s physical exam was remarkable for a macular, blanching, non-vesicular, erythematous rash on all extremities, chest, and back, sparing the palms, soles, and oral mucosa. Lungs were clear to auscultation in all fields. Further diet history detailed consumption of two mangos two days prior to the onset of the rash. The patient’s wife, who accompanied him to the ED, had also consumed mangos two days prior but was asymptomatic. Although both the patient and his wife handled the mango peels, the wife did not endorse prior plant exposures resulting in rash.

Several reports have noted that mango dermatitis appears similar to poison ivy dermatitis.

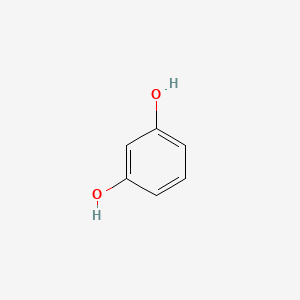

Supposedly, this cross-reactivity may be due to similarity in structures for some of the molecules found in the peels of mangoes. For instance, some of these mango-derived molecules contain a ring structure called 5-resorcinol, which differs from catechol’s structure in only the spacing of the hydroxyl groups (catechol has each alcohol adjacent/ortho to one another while 5-resorcinol has the alcohol groups meta/2 spaces away).

For instance, one of these molecules, named 5-(8'Z,11'Z-heptadecadienyl)-resorcinol, has the following structure:

So it’s possible that T-cell responses to Urushiol metabolites may also cross-react to metabolites of resorcinol-like structures. However, given the complexities of allergies one cannot dismiss the possibility of other sensitizing agents inducing cross-reactivity.

For instance, there has been some debate over whether cashew or pistachio allergies may lead to allergies with mangoes, so the direct link between mangoes and poison ivy may not be fully substantiated, and made even more ambiguous by way of prior exposure to other allergens.

As someone who has grown up eating mangoes while also experiencing plenty of seasonal poison ivy rashes, I don’t recall having this issue of mango dermatitis occurring. However I never peeled my own mangoes during those rashy summers, and many of these compounds appear to be reserved to the peels of mangoes in particular,6 so I may have lucked out in not being exposed.

Either way, it makes for a rather interesting thing to consider when thinking of how even our responses to one type of plant may influence how we respond to others.

Things to look out for

As with any compound, what once may have been a cause for concern is now being looked at for other therapeutic possibilities. Urushiol-like compounds are being examined for their possible anticancer properties.7,8 This is another example in which the properties of a compound can either be seen as beneficial or detrimental to the human body.

But, for most of us we may be primarily concerned with coming across such Toxicodendrons as we venture out into nature.

In addition to “leaves of three”, keep in mind the following:

Some of these Toxicodendrons can take on different appearances throughout the seasons. For instance, in early spring the leaves may take on a reddish hue, or a mixture of red/green pigmentations. It’s normally summer colors that we associate with these plants with the predominately green leaves. However, newer leaves may take on a reddish appearance. In fall, the leaves may turn a red/yellow appearance, and turning pure red in the winter prior to falling off. Poison ivy can also present with white berries, so use these as cues to look out for aside from just the leaf organization.

Burning of these plants, which can sometimes come accidentally from the burning of wood invaded by the vines of Toxicodendrons, can be extremely dangerous, as this will release Urishiol into the air. Inhalation may cause an allergic reaction within the lungs and throat which can be far more dangerous than just the topical exposure.

Some homeopathic lotions, creams, or lip balms may contain Toxicodendron as an ingredient.9 The levels of Urishiol vary, but it’s worth considering taking precautions when using such products, especially if you are more prone to hypersensitivity when it comes to Urishiol. Check labels for mention of these ingredients, which may note “Rhus tox” on the label.

Treatment for poison ivy dermatitis follows a similar route as other allergic reactions. Topical corticosteroids may help to alleviate the inflammation and hyperactive immune response. Calamine lotion and other over-the-counter agents may help to relieve the itchiness. Check for products that may contain menthol or other soothing ingredients. Antihistamines may also help to attenuate some of the allergic response as well.

So as one engages in the frivolities that this holiday weekend provide, and as people begin to venture forth into nature, beware of where you step unless you’d like a bout of the itches!

Substack is my main source of income and all support helps to support me in my daily life. If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

This name can be confusing, as it is widely found in various parts of Asia. The tree also goes by the name Japanese lacquer tree or Japanese sumac, which adds even more confusion.

Note that the geographical regions mentioned in this article are relative and based upon what information I have come across. The CDC notes that both poison ivy and poison oak can be found all across North America. It appears that poison sumac is mostly prevalent in eastern states including regions of Canada.

Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron Toxicity. [Updated 2023 May 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866/

Oka, K., Saito, F., Yasuhara, T. and Sugimoto, A. (2004), A study of cross-reactions between mango contact allergens and urushiol. Contact Dermatitis, 51: 292-296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00451.x

Yoo, M. J., & Carius, B. M. (2019). Mango Dermatitis After Urushiol Sensitization. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine, 3(4), 361–363. https://doi.org/10.5811/cpcem.2019.6.43196

In answering the question of why exactly Toxigodendrons contain these compounds, the answer may lie in the fact that resorcinol-like compounds appear predominately within the peels of mangoes. These compounds are noted to be resin-like, and so they may serve some form of structural support or defense, possibly by way of forming a waxy coating on the outside of the plant that regulates gas exchange and release of moisture, similar to the intent of Apeel.

Jeong, J. H., & Ryu, J. H. (2022). Urushiol V Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Enhances Antitumor Activity of 5-FU in Human Colon Cancer Cells by Downregulating FoxM1. Biomolecules & therapeutics, 30(3), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.4062/biomolther.2022.008

Qi, Z., Wang, C., & Jiang, J. (2018). Synthesis and Evaluation of C15 Triene Urushiol Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents and HDAC2 Inhibitor. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 23(5), 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051074

Zhang, A. J., Aschenbeck, K. A., Law, B. F., BʼHymer, C., Siegel, P. D., & Hylwa, S. A. (2020). Urushiol Compounds Detected in Toxicodendron-Labeled Consumer Products Using Mass Spectrometry. Dermatitis : contact, atopic, occupational, drug, 31(2), 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1097/DER.0000000000000544

When hiking, carry Wet Ones or alcohol swabs and as soon as you touch that plant (also: stinging nettle is a problem in Indiana - I'm sure it's across the Midwest, and South, too.) swab the skin with alcohol to "break" the oil. The times I have done this = no rash. There is also a vine which grows where the poison ivy grows, called Jewelweed The juice from the Jewelweed will also break the oil, and has enzymes to counteract the poison ivy. I have also had some success with Jewelweed, but you can't always find it when you get exposure.

I just came back from Far North Queensland, where mango is a major product. Apparently, those who work in the mango processing plants develop rashes - mango rashes are common and real (I didn't know that prior to this trip). We do not have poison ivy downunder (though, there are fatal tree versions of the stinging nettle). So the mango rashes here in Oz do not relate to exposure to toxicodendron.

The amusing story here: when my now-husband, from Australia, came to visit me in Indiana. Australia has a reputation for things that can kill you: crocs, snakes, spiders, stingers, cone snails.

I had to teach him about poison ivy, stinging nettle. He said, "At least Australia doesn't have these kinds of plants - EVERYWHERE!" Another joke we tell is that when you fly to Australia, the snakes, spiders & crocs are waiting for you at the airport (in other words, encounters are rare).

THEN, we dangled our feet in an Indiana creek, and up came a cottonmouth. I guess the world is dangerous wherever you are!

I hear it does not affect goats, which would make them useful eaters.