Another pivotal paper bites the dust- the alleged "pluripotency" of mesenchymal stem cells

A 2002 paper with more than 4,000 citations has been retracted due to allegations of manipulation, adding to the ever-growing list of bad papers being retracted.

Edit 7.13.2024: There was no link for the 2007 Nature editorial in the initial publication of this article. Also, a citation was not provided for the Figure taken from the Jiang, et al. paper. A respective link and citation has now been included.

When covering the fallout from the Lesné, et al. retraction I mentioned that the groundbreaking Alzheimer’s paper was the second most-cited paper in history to be retracted.

The most seminal paper in Alzheimer's pathology has been retracted due to allegations of fraud

Over the past three years I have brought attention towards Alzheimer’s research and controversies surrounding the field, first starting with questions regarding the fast-tracked approval of the immun…

In reality, when Science covered the retraction in early June it actually mentioned that it was the most cited paper to receive a retraction at the time. And yet within a few days another paper swooped in, taking that moniker.

This time a 2002 paper with more than 4,000 citations1 was the one to see a retraction. More specifically, another groundbreaking paper from the world of stem cell research claiming that mesenchymal stem cells exhibit pluripotency was the one to come under fire.

A Timeline of Tumultuous Stem Cell Research

Prior to this paper from Verfaillie’s team, many researchers were looking into the pluripotent nature of embryonic stem cells. Pluripotency refers to the ability of stem cells to differentiate into different cell types, and so such a research endeavor could prove extremely useful within the field of medicine as it would mean being able to treat all sorts of maladies by replacing dysfunctional/damaged cells and tissues with cells that can differentiate into the needed cells.

Of course, this sort of research was extremely controversial due to the source of these cells, with newly elected president George H.W. Bush issuing a ban on federal funding for newly created embryonic stem cell lines in August 2001.2 Thus, researchers were trying to find other cells that could also exhibit pluripotency but didn’t come with the same degree of ethical baggage.

Thus, the arrival of a paper suggesting a viable alternative would prove timely (and groundbreaking) amidst the ongoing controversy, and would allow a huge pivot in the field.

Here, Verfaillie’s team examined mesenchymal stem cells- a type of stromal cell found predominately within bone marrow that shows multipotency in that they can differentiate into either bone, muscle, fat, or cartilage cell types. However, her team argued that these stem cells- when put into the right environment- may actually show pluripotency.

Note the difference in prefix- multipotency refers to a cell that can differentiate into a few (yet fixed) number of cell types. This is in contrast to pluripotency, which may refer to a cell’s capability to differentiate into any cell type.

Thus, such a finding would revolutionize the field of stem cell therapy. Not only would it serve as a more ethical alternative to embryonic stem cell research, but it would also suggest that stem cells may show broader differentiating capabilities than was initially thought. Many adults have their own repertoire of stem cells, and so such a finding would also mean that easily sourced and widely available stem cells could be used for all sorts of therapies.

And so, a huge upheaval was seen within the field of stem cell research, and within the following years funding and research pivoted towards examining various stem cells (mostly bone marrow stem cells) for their pluripotent capabilities.3 Verfaillie herself appeared to enjoy a period of fame as accolades and praise was thrown her way with such a groundbreaking finding, resulting in her own research seeing a boost in funding and helped to leave to raise the prestige of the University of Minnesota where she was employed.

However, not everyone was in agreement with the findings, and among the crowd of cheering scientists who lauded Verfaillie’s work several dissenting voices came out, arguing that such a breakthrough would circumvent the longheld assumption that only embryonic stem cells showed pluripotency while differentiated cells are completely fixed in their cell type. Given that prior attempts to find other cell types were met with serious scrutiny of replicability, there were viable concerns that sensationalist headlines and reports would be driving much of the appraisal of Verfaillie’s work rather than the actual merit of the research.

This controversy would continue over the next few years as several researchers were unable to replicate the pluripotency that was alleged to have been found by Verfaillie’s team, with additional questions arising regarding the specific cell lines in question that were used.

This was highlighted in several articles, including one published in Nature in 2007:

Verfaillie's work has since proven exceedingly difficult to replicate, although some groups have reproduced certain parts. Earlier this year, after spending several years learning to work with MAPCs, Scott Dylla, a former postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Stanford University biologist Irving Weissman, was able to use MAPCs to make blood-forming haematopoietic stem cells in mice5. But although many groups have tried, none has managed to repeat the key aspect of Verfaillie's paper — injecting MAPCs into an embryo to create all the major cell types of the body. “I have not seen any convincing data showing that anyone has repeated the chimaera experiment, so I don't think this part of it is true,” says Rudolf Jaenisch of the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose lab tried and failed to reproduce the work.

MAPCs refer to multipotent adult progenitor cells, or nonhematopoetic stem cells found in bone marrow i.e. cells that do not differentiate into “blood cells” such as red, white, or platelet cells. These were the cells that were argued to show pluripotency and thus became the focus of stem cell research for many scientists.

It was around this time that many questions began to make their way into the spotlight, and eventually a paper published in 2001 from Verfaillie’s team4 came under fire from a pair of investigators named Peter Aldhous and Eugenie Reich who at the time were working for the science outlet New Scientist. The two were critical of Verfaillie’s original findings from the Nature paper, and they raised skepticisms regarding alleged duplications found in several of the 2001 Blood paper’s figures- figures which also strangely appear in the groundbreaking 2002 Nature paper.

After internal investigations the 2001 paper originally published in Blood was retracted, with blame being placed onto the first author of the paper while Verfaillie was implicated in “insufficient oversight”, as mentioned in a 2008 Nature post5 highlighting the retraction:

The University of Minnesota has asked the journal Blood to retract a high-profile paper on adult stem cells following a university investigation. The paper reported that mesenchymal stem cells isolated from adult bone marrow could generate a surprising number of tissues (M. Reyes et al. Blood 98, 2615–2625; 2001), but other labs had trouble replicating that work. The investigation concluded that the paper included manipulated images.

Lead author Catherine Verfaillie, now director of the Stem Cell Institute at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, was cleared of academic misconduct but blamed for insufficient oversight. That suggests the blame rests with the only other scientist under investigation, Verfaillie's graduate student Morayma Reyes, now at the University of Washington. However, the findings regarding Reyes cannot be released because of privacy laws. Reyes says that she made "honest unintentional errors".

Although Verfaillie was not indicted on actual misconduct the controversies led to growing concerns that these so-called “multipotent turned pluripotent” cells may not be all that they were alleged to be.

But what exactly was wrong with the 2002 Nature paper?

Aside from questions regarding the flow cytometry results, questions were raised regarding some of the images that were provided with respect to the engraftment of mice.

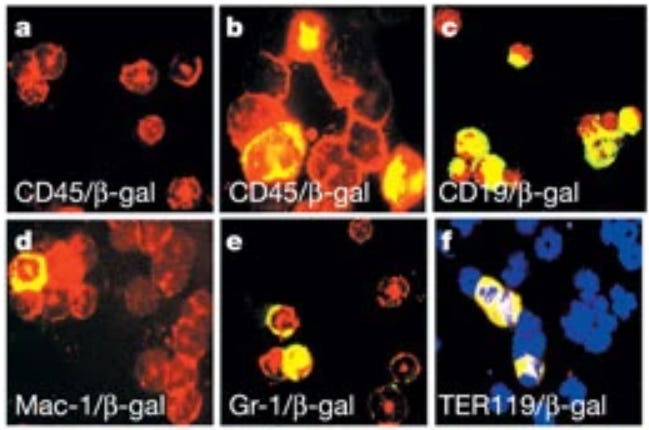

More specifically, one portion of the paper examined the effects of engraftment of mice with MAPCs. A special type of MAPC called ROSA26 which showed expression for the enzyme β-galactosidase was injected into mice that were several weeks old. Mice were later examined to see whether β-gal was detectable in a portion of the tissues and cells collected, which would indicate successful engraftment and differentiation of MAPCs into the specific cells of that region.

Here, the authors allege that not only were cells containing β-gal detected in bone marrow and spleen, but also appear to have been detected in tissues of the lung, liver, and intestine. This portion of the study is where the main issues with possible manipulation were brought up.

Now, readers may get a better understanding from working backwards as a means of understanding the alleged manipulations. In this case, let’s look at the initial reasons for the retraction6:

The Editors have retracted this article because concerns have been raised regarding some of the panels shown in Figure 6, specifically:

-the lower half of Figure 6a (CD45/β-gal) appears to be identical to the upper half of Figure 6e (Gr-1/β-gal)

-the upper right corner of Figure 6m appears to have two regions that are duplicated within the upper right corner itself

Here is the portion of Figure 6 in question, which focuses on results from cell staining of samples collected from bone marrow. Again focus on (a) and (e):

Can you spot the issue? If not, here’s Elisabeth M Bik7, a biologist-turned-sleuth in research misconduct who noted the problem and posted a commented on PubPeer highlighting the concern:

That’s right- it appears that two of the slides used in this paper seem to be the same exact slide, only shifted up/down.

Now, this raises some serious questions regarding this paper. Note that (a) is considered the reference/control mouse, and therefore shouldn’t fluoresce with β-gal staining which is likely the yellow color seen among the various slides. (e) was allegedly taken from a mouse that was engrafted with the ROSA26 MAPCs, and therefore should (if the authors’ hypothesis of pluripotency was true) fluoresce if β-gal is present.

Here, readers can see the entire contradiction at play: clearly this slide can’t reference both a control and an engrafted mouse- we should see either/or staining for β-gal, not both!

This begs a serious question- which mouse were these slides derived from? If this image was taken from the engrafted mice why use it as the reference slide as well- obviously if control mice didn’t show any expression of β-gal to begin with any samples sourced from control mice shouldn’t fluoresce yellow when stained.

The other explanation is more likely, although this is mere speculation. Instead, it’s quite possible that the slide may have been taken from the control mouse and possibly manipulated to show fluorescence.

In essence, it’s possible that the MAPC engraftment did not actually take hold and differentiate, but researchers manipulated their results to make it seem as such.

There’s no way to prove this to be the case, and coverage of this paper has not entertained what the ramifications of using the same slide for both a control and experimental result could be for the conclusions of this paper.

However, this seems like the likely scenario, and likely why the retraction came with the following comment (emphasis mine):

The original images for Figures 6a, 6e and 6m could not be retrieved by the authors; therefore the Editors no longer have confidence that the conclusion that multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPCs) engraft in the bone marrow is supported.

Even this retraction is relatively conservative. It doesn’t bring into question whether the rest of the paper’s findings are questionable, especially since the other results seem to relate to the initially proposed hypothesis that MAPCs can differentiate into other cells as the detection of β-gal among liver and lung tissue may suggest possible MAPCs differentiating passed their expected capacity.

That being said, it’s likely that this is the only place where clearly questionable manipulation can be recognized, and is at least enough evidence to raise concerns over possible manipulation across the rest of the paper even if there is no conclusive evidence.

Bad science and the institutions and public that spurs its continuation

There’s many parallels that can be drawn between the retraction of this stem cell paper and the previously covered Alzheimer’s paper:

Both papers were considered groundbreaking, and essentially revolutionized their respective fields. Such research would, of course, gain far more attention and will be far more likely of receiving funding.

Those in the public who may know nothing about the research being conducted and the questionable methodologies may otherwise use such papers as justification for changes in policy and research avenues. In the case of Versaillie’s stem cell paper the findings were used by policymakers to move funding and research endeavors away from embryonic stem cells and towards these MAPCs.8 In the case of Lesné, et al. people may wrongly infer that there is a possible treatment for Alzheimer’s- we just need to push funding and attention towards targeting these amyloid subtypes.

Although both papers were met with widespread praise researchers would fail to replicate many of the findings from said papers, owing again to the growing replication crisis happening in science and the highlights the many pitfalls in research auditing.

What may be rather shocking to readers is that, at the time of the stem cell paper’s publication, Versaillie was employed at the University of Minnesota. Bear in mind that both Katherine Ashe- the lead author of the Alzheimer’s paper- and Sylvaine Lesné- the first author of the paper- were and still are employed by the University of Minnesota.

For those who don’t know the University of Minnesota is considered one of the top public research universities in the US, and is considered among one of the top research universities globally.

It’s an honor that the university proudly displays including under their “Research” portion of their website:

Thus, we can see the heavy incentive structure that is likely at play in academic research. Many of these institutions have a reason to put out eye-catching, headline-grabbing studies that argue to revolutionize a field. Not only does this bring attention and prestige to the researchers, but it also adds to the prestige of the university, making it a place that would entice prospective researchers, students, and possible investors.

But there’s also an incentive to downplay possible academic malfeasance. Universities may try to obfuscate bad press associated with paper retractions- especially if due to alleged fraud- and therefore may hinder the retraction process for as long as possible, even if it means people may continue to cite, research, and push funding towards the very thing that is being brought into question.

This appears to be the case when it comes to Alzheimer’s in which many researchers are now even wondering if the near 18 years of research and billions of dollars spent were all wasted. The same may be said for stem cell research as well…

But the blame doesn’t just fall onto the institutions. After all, headline-grabbing research is conducted due to the fact that these are areas that will likely be covered by those in the press.

It follows that most research is put towards dementia, cancer, HIV, and other diseases that people are interested in rather than some obscure disease that may afflict one in a million people since these diseases are more likely to afflict the common person or someone they know and love. We can see this even when it comes to endangered species where animals that are not cute and cuddly don’t get the same degree of attention as those with adorable faces that we can plaster onto magazine covers.9

There’s a cyclical, and rather insidious relationship between institutions, reporters/journalists, and the public, and it’s this precarious cycle that results in the publication of so much bad science.

Peter Aldous mentions some of these egregious issues in his article published in Scientific American regarding the stem cell paper retraction. I encourage readers to check out that article, but here are a few noteworthy excerpts [context included]:

The paper’s [Versaillie’s 2002 Nature paper] tortured history illustrates some fundamental problems in the way that research is conducted and reported to the public. Too much depends on getting flashy papers making bold claims into high-profile journals. Funding and media coverage follow in their wake. But often, dramatic findings are hard to repeat or just plain wrong.

[…]

I understand why universities and journals are reluctant or slow to take corrective action. But the saga of Verfaillie’s Nature paper reveals a deeper problem with perverse incentives that drive “successful” careers in science. A highly cited paper like this is a gateway to promotions and generous grants. That can starve funding to more promising research.

My profession of science journalism shares the blame, often fixating on the latest findings touted in journal press releases, rather than concentrating on the true measure of scientific progress: the construction of a body of repeatable research. When doing so, we mislead the public, selling a story of “breakthroughs” that frequently amount to little.

As I have mentioned many times in my coverage of Alzheimer’s immunotherapies the public needs to be more aware of the influence they have on research. It’s the public’s yearning for awareness and treatments that results in the type of research that gets conducted, or the therapeutics that make their way to market.

Scientists are not the only ones responsible for the insidious incentive structure that pervades science. Journalists and those in the public play a key role, and when both journalists and the public remain ignorant of research malfeasance then we will continue to be preyed upon by those who don’t hold our best interest in mind.

It is why we need journalists who are earnest in their coverage of studies, and we need a public who understand the need to show discipline, restraint, and curiosity in order to push for more honest research instead of things that can make for easy talking points.

Otherwise science will continue to exist in this sad state for decades to come.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Jiang, Y., Jahagirdar, B., Reinhardt, R. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 418, 41–49 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00870

Murugan V. (2009). Embryonic stem cell research: a decade of debate from Bush to Obama. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 82(3), 101–103.

Bear in mind that by 2007 another revolution occurred within the field of stem cell research. This came about due to researcher Shinya Yamanaka who found that adult, differentiated cells could be induced into a pluripotent-like state (referred to as iPS for induced pluripotent stem cells). Such a finding was so groundbreaking that Yamanaka became one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2007. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like the field has progressed to a huge degree, as the method in which these cells were made to be pluripotent required manipulations that may be oncogenic, resulting in limitations in clinical research utilizing these cells.

Reyes, M., Lund, T., Lenvik, T., Aguiar, D., Koodie, L., & Verfaillie, C. M. (2001). Purification and ex vivo expansion of postnatal human marrow mesodermal progenitor cells. Blood, 98(9), 2615–2625. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v98.9.2615 (Retraction published Blood. 2009 Mar 5;113(10):2370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186288)

'Manipulated' stem-cell paper faces retraction. Nature 455, 849 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/455849d

Jiang, Y., Jahagirdar, B.N., Reinhardt, R.L. et al. Retraction Note: Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 630, 1020 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07653-0

Bik has been pivotal in finding manipulated figures/images across many studies, and was in fact a key player in noticing issues with respect to the Lesné, et al. paper.

Bear in mind that I am not arguing that we should be using embryonic stem cells for research. Rather, I am pointing out that people will use anything that pushes their narrative even said things are not substantiated by good science. As such, even if we argue that embryonic stem cell research is entirely unethical we shouldn’t use bad science to support our position.

It appears that perspectives are pivoting in recent to try and endear people to more “ugly” animals, as is the case for the now well-known blobfish whose ugliness has garnered it a large degree of attention. I guess this is a case of bad press still being press nonetheless.

Why would a renowned scientist resort to doctoring their own paper? Getting free funding and stable employment is not enough. Public recognition and respect is not enough. Being published is not enough. What’s the next best prize?

Dealing with one of the most difficult conditions for families… What has happened to basic human decency and honesty? You can extrapolate this: if they can manipulate such big issues, what about minor conditions and health in general - do they care at all?

Has any of those who put their names as authors been held liable? Or are they in business as usual?

I don’t mean “they are guilty”. But… they must have been working on this paper for quite a time. Sixteen (16) authors. They had to make a decision at some point. And then proceed with it, and submit the paper as a follow-up to that decision.

Now that the publisher is ashamed of their own negligence, you are not even allowed to read the paper - you have to pay them 30 quid to get a PDF. Weird logic…

Thank you. As a young, naïve graduate student, the first scientific fraud I was exposed was the Spector / Racket debacle. I was stunned.