A Looming "Tripledemic"?

Could there be an upcoming convergence of RSV, Influenza, and COVID for children coming this winter?

Recently an unusual surge in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is being experienced across the nation as well as in many pockets across the globe. Rates of infection appear to be occurring predominately among toddlers and young children.

Such an unusual occurrence is raising questions as to what may be causing this strange surge, and with winter coming some doctors have raised concerns that the we may be experiencing an outbreak of 3 seasonal viruses concurrently: RSV, Influenza, and COVID.

In relation to COVID, this may be a serious concern as COVID tends to show a mortality rate that increases with age, suggesting that young people are far less likely to suffer severe complications or death from the virus compared to the elderly.

In contrast, both the elderly and the young are susceptible to severe disease from either RSV or the flu, meaning that this outbreak among young children may be a cause for some fears in the coming months.

Right now the main concern appears to be the outbreaks of RSV, although some surveillance data suggests that flu rates are increasing in the past few weeks as well.

One thing adding to this confusion is the fact that RSV outbreaks reappeared since the end of 2021 while there didn’t appear to be a similar outbreak of the flu within that similar timeframe.

For instance, a study1 from August 2022 looked at surveillance data on RSV and the flu in South Korea showing a spike in RSV infection starting in November 2021 and peaking in January 2022. At the same time, there didn’t appear to be a similar outbreak of flu.

The researchers note the following:

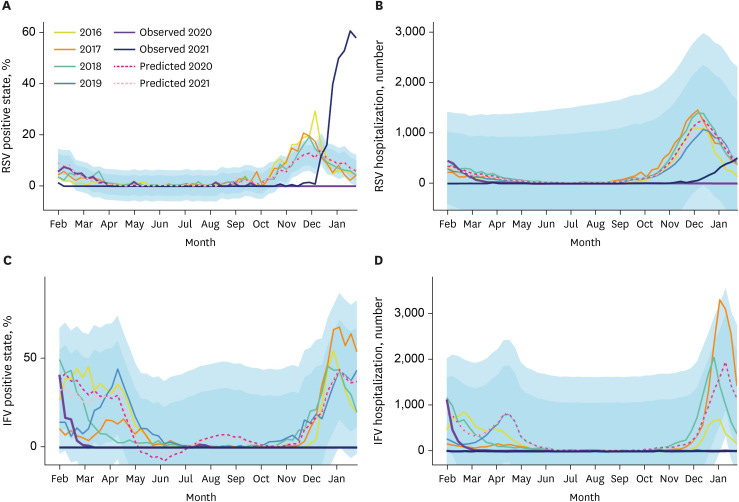

From April 2020, when the broad NPIs for COVID-19 were implemented from February 2020 to early November 2021, there were no outbreaks of either RSV or IFV, with the exception of sporadic cases of RSV (Fig. 2). The RSV outbreak began to occur from the end of November 2021 and peaked in the third week of January 2022, with a weekly positivity rate of 61% under specimen-based surveillance (Fig. 2A).

[…]

The weekly positive rates and number of hospitalizations for IFV infection were significantly lower in the NPI period than in the pre-NPI period for two consecutive seasons (i.e., 2020–2021 and 2021–2022) (Fig. 2C and D). In the 2021–2022 season, there was no positive cases of IFV among the 4,902 specimens under the specimen-based surveillance. In addition, the hospitalization rate for IFV under the clinical surveillance was extremely low at 1.3% (95% CI, 0.03–60.8%) of the pre-NPI period and 1.2% (95% CI, 0.3–∞%) of the predicted value (Table 2).

Surveillance data from South Korea may not explain much since other regions deal with differences in climate, temperature, and commute among citizens.

However, the researchers also included surveillance data from other countries showing similar patterns including the US.

Here, heatmap data shows higher infection rates with an increasingly red hue. Note that in the first year of the pandemic there doesn’t appear to be any notable rates of circulating RSV or flu among the surveyed countries in spring 2020 up until fall 2021 (aside from Taiwan in late 2020 showing an apparent outbreak of RSV as indicated in Fig. A). In fall 2021 there are various outbreaks of RSV across all of the countries surveyed while few countries show similar outbreaks of the flu with Russia, France, and Mexico being standouts.

All of this creates a strange predicament. The onset of RSV after taking a nearly yearlong pause and showing delayed and unseasonal outbreaks is concerning. Paired with the fact that the flu hasn’t been circulating to a great degree for some time until now also raises questions as to what could be the cause, especially with a possible looming “tripledemic” in the coming months.

So what’s the cause of this anomaly?*

*Note that these are ideas that have not been fully fleshed out.

1. Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

The obvious argument is to suggest that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have altered the common flow and transmission of RSV and the flu among the global population.

Both RSV and the flu are argued to have similar modes of transmission, usually through mucus membranes and large droplets that spread through coughs and sneezes. This would contrast SARS-COV2, which was originally argued to behave more like the flu until evidence suggested that not to be the case, and that SARS-COV2 likely spreads through small aerosols that remain suspended for quite some time in an enclosed environment.

It would explain why lockdowns had such minimal (if any) effects on the spread of COVID while RSV and the flu may have disappeared during the time of drastic lockdowns.

However, that wouldn’t quite explain the strange lack of the flu during the winter 2021 months.

One suggestion proposed could be that RSV is endemic while the flu may require international modes of transmission. As such, the lack of having widespread travel even as lockdown measures loosened up may explain the delayed spread of the flu.

The study from Kim, et al. points to the lack of the international travel as being a possible explanation, even noting that flu vaccine uptake in South Korea is quite low along with the relatively low effectiveness of the flu vaccine to begin with (emphasis mine):

The disappearance of influenza outbreaks in South Korea for two consecutive seasons despite the gradual easing of the domestic NPIs means that the origin of annual seasonal influenza outbreaks in South Korea is not related to the extent of domestic NPIs, but to the quarantining of overseas travelers/immigrants. Unlike other respiratory viruses such as RSV, bocavirus and adenovirus, whose sporadic cases have been reported since COVID-19 pandemic, it is noteworthy that the number of influenza cases in the national sentinel surveillance was almost zero for 2 years in the COVID-19 era. Excluding clinical surveillance data containing rapid antigen test-confirmed cases with a risk of false-positive cases, only 2 out of 8,076 outpatients with ARI (30 weeks and 31 weeks in 2020, one case each) since April 2020 were IFV positive, as per PCR results. It is unlikely that the universal influenza vaccination for the general population had a significant effect on its disappearance because the effectiveness of the seasonal influenza vaccine is usually around 40–70%, and the vaccination rate of the general population is less than 50% in South Korea.15 Rather, considering that the RSV (basal reproduction number, R0 = 1.2–7.1) and IFV (R0 = 1.3–1.7) have similar modes of transmissibility, it is possible that the virus inflow from overseas during the seasonal influenza outbreak period in South Korea was blocked due to international travel restrictions.3,16 The incubation period (1–4 days) and the duration of viral shedding (5–10 days) of the IFV are relatively shorter than those of the SARS-CoV-2; therefore, IFV influx from other countries was theoretically interrupted due to the 1–2 weeks of self-quarantine and symptom monitoring of overseas travelers.17 Moreover, according to a report by International Air Transport Association, international air travel in 2021 was only 22% of the 2019 frequency, with the highest reduction in the Asia-Pacific region including South Korea (https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/). Therefore, it is possible that the influx number of overseas travelers with influenza itself had decreased markedly. Monitoring how seasonal influenza occurs and spreads around the world as international travel restrictions are eased in the future may provide intriguing findings.13,18

The researchers even note that similar results may have been seen in Taiwan and Australia, which may have relaxed travel restrictions while still barring international travel and therefore may point to endemic spread of RSV contrasted with international spread of the flu (note this assumption does come with caveats in surveillance data and actual rates of RSV infection):

The rates of RSV infection in the 2021–2022 season suggest that the seasonal outbreak of RSV infection in South Korea may have started from an endemic source, and the exact origin is still unknown. Similarly, Taiwan and Australia also reported the occurrence of RSV infection without an influenza outbreak when the domestic NPIs were relaxed and overseas entry was strictly restricted.8,19

These assumptions may not be similar for other countries, but note that the US ended the international travel embargo in November of 2021 which may reflect similar changes for other countries and may indicate that lack of international travel may have halted much of the spread of the flu as seasonality may have been disrupted.

2. Immunity Debt

A few months ago both Peter of All Facts Matter and I raised comments that the rise of childhood infections is likely a consequence of immunity debt.

Just recently Brian Mowrey wrote a post criticizing arguments over irrational maneuvers to have selective cleanliness that attempt limit exposure to bad microbes while embracing exposure to good microbes, rather than just providing exposure to to all microbes and creating a robust form of immunity that our species has always known of prior to modernization (or viral safetyism as Brian puts it).

One report from Garg, et al.2 describes the immunity debt predicament the following way:

As regular life resumes following the easing of COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions, the exposure to various infectious viruses and bacteria—such as influenza, chickenpox, and RSV—will increase as well. However, the question remains on the severity of these new RSV epidemics occurring soon after a year of low activity. Immunity debt is defined as a lack of immune stimulation and protective immunity due to reduced exposure to a given pathogen, leaving a greater proportion of the population susceptible to the given pathogen in the future [56,57,58,59,60]. Immunity debt involves a complex mechanism involving interplay of innate and adaptive immunity (including training of innate immunity, development of immune memory), intestinal microbiota, exposure to pathogens, and immunization [61].

Some authors have suggested a combination of increased exposure following re-opening of schools, nurseries, and kindergartens, easing of travel restrictions, and cessation of mandatory facemask-wearing (non-pharmaceutical interventions) following COVID-19 vaccination, might mean that the future RSV outbreak might be more severe compared to previous seasons [21,62,63,64].

The argument here tends to be consistent: humans are not meant to be isolated, living away from each other and away from pathogens.

The lack of exposure to any pathogens results in an immune system that isn’t properly trained to deal with the insults thrown by nature. As adults, we may fall back onto the immunity that we accrued when we were younger; immunity we likely earned from constant exposure to pathogens over the years.

For children, this is clearly not the case. The prolonged isolation and NPIs pushed onto children means that they were not able to form that much-needed immunity during their formative years and are now needing to catch up.

Unfortunately, the effects here aren’t similar for children as it would be for adults.

While the elderly are more susceptible to COVID, it’s the young that are more likely to suffer severe illness and death from RSV and the flu.

For instance, take this information on RSV3:

The human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is one of the most common viruses to infect children worldwide and increasingly is recognized as an important pathogen in adults, especially the elderly. The most common clinical scenario encountered in RSV infection is an upper respiratory infection, but RSV commonly presents in young children as bronchiolitis, a lower respiratory tract illness with small airway obstruction, and can rarely progress to pneumonia, respiratory failure, apnea, and death.

[…]

RSV is a widespread pathogen of humans, due in part to the lack of long-term immunity after infection, making reinfection frequent. It infects 90% of children within the first 2 years of life and frequently reinfects older children and adults. The majority of patients with RSV will have an upper respiratory illness, but a significant minority will develop lower respiratory tract illness, predominantly in the form of bronchiolitis. Children under the age of one year are especially likely to develop lower respiratory involvement, with up to 40% of primary infections resulting in bronchiolitis. Worldwide, it is estimated that RSV is responsible for approximately 33 million lower respiratory tract illnesses, three million hospitalizations, and up to 199,000 childhood deaths; the majority of deaths are in resource-limited countries.

In a paradoxical, upside-down state of affairs the NPI measures taken to limit the spread of COVID (which, again, could be argued to have been horrendously fruitless) may have put children at risk of diseases that they are at much greater risk of dying from.

This once again comes as an example of irrational behaviors from adults, focused more on parochial solutions rather than a broader, nuanced take that may be causing children to suffer. Children are far behind their infection schedules, and that means that a lot of catching up must be done.

This also means that one must be critical of the continuation of seasonal NPIs. Many doctors and scientists may argue that NPIs reduced the spread of RSV and the flu, but such an argument would enforce the inevitable; people need to get sick, and the longer it is delayed the worse the consequences.

As such, NPIs do nothing but prevent the one thing that has served our species for hundreds and thousands of years. Doctors should remember the long-term consequences of such short-term, parochial solutions.

Winter, and a “Tripledemic”, is Coming

As of now the only information available in regards to a “tripledemic” are preliminary in nature. We know that RSV outbreaks continue, and that we may be entering a phase of the flu outbreak. We may also expect that seasonality of COVID may all converge into 3 circulating pathogens.

All of this should serve as a reminder of the dangers that narrow-minded solutions can have on entire populations. There’s no doubt that continuous lockdowns have made most people worse off, and we are now reaping the consequences of such ridiculous measures.

I will point out that several arguments have been made that the current outbreaks are a consequence of the COVID vaccines causing immune dysfunction, in which case I would argue that the evidence wouldn’t support such an argument but rather points more towards the consequences of immunity debt.

As noted by Vinay Prasad in his piece for Bari Weiss, as well as in Heather Heying’s post from today the uptake of COVID vaccines among children remain low with a many adults being skeptical of giving their kids these experimental jabs. It’d be hard to argue that what we are seeing are a consequence of the vaccines given that this is occurring predominately among children who are more than likely not vaccinated.

In any case, as we approach winter it should be a time to remember to do things that can help yourself and your family. Note that these aren’t prescriptions, but it may be worth considering examining your diet, exercise, and sleep schedules. Consider how much sunlight you are getting before it becomes too difficult. Consult with medical professionals on supplementations and other factors that may help boost your immune system.

And more importantly, remember that pathogens are a part of life. By delaying the inevitable we may be doing more harm than good. We should be creating antifragile children; not damaged ones.

If children are the future, we must remember that children must get sick to protect them in the future. It’s another example of not allowing kids to be kids and the consequences that follow.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists outside the mainstream.

Kim, J. H., Kim, H. Y., Lee, M., Ahn, J. G., Baek, J. Y., Kim, M. Y., Huh, K., Jung, J., & Kang, J. M. (2022). Respiratory Syncytial Virus Outbreak Without Influenza in the Second Year of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A National Sentinel Surveillance in Korea, 2021-2022 Season. Journal of Korean medical science, 37(34), e258. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e258

Garg, I., Shekhar, R., Sheikh, A. B., & Pal, S. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on the Changing Patterns of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections. Infectious disease reports, 14(4), 558–568. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr14040059

Jain H, Schweitzer JW, Justice NA. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. [Updated 2022 Jun 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459215/

Yep low immune exercise (exposure) and immunosupression by stress (poor diet, emf, food toxicity and vacsines toxicity). .

Appreciate the highlight.

Regarding flu, I am not convinced there is a mystery here. One of the things that was resoundingly clear from my re-build of the history of flu research is that there was never an expectation that flu would circulate every year before the PCR era. So either flu changed after the 80s, to become truly annual as opposed to sporadic-annual, or flu remained sporadic-annual and PCR introduces extra detection compared to using observations of illness, ferret/egg isolation, and seropositivity to measure flu. The very first influenza A outbreaks recorded with those three measurements were 1935/36, 37, 39, 41, 43/44, 46/47 (https://unglossed.substack.com/i/64504855/home-run).

Flu remains sporadic after H1N1 reemerges from a lab and co-circulates with H3N2 in 1977.

So, the mystery of why PCR stopped flagging flu cases in 2020-21 is not interesting unless it can be shown by some other statistic that flu actually changed to be yearly. I haven't followed-up to see if such other statistics exist.