Remdesivir: COVID's Standard of Care that May be Causing more Harm than Good (REVIEW)

Part III-1: Remdesivir in the Age of COVID

Even though the purpose of this series is to examine the possible toxicity of Remdesivir, it’s important to examine whether Remdesivir is even effect. In my mind, there’s no point in examining how dangerous a drug is even it’s not even effective. So we’ll take a look at Remdesivir’s effectiveness against SARS-COV2.

Remdesivir Against SARS-COV2

Nonclinical Evidence Against SARS-COV2

When it comes to SARS-COV2, we can see how prior in vitro evidence helped to bolster Remdesivir’s consideration as an antiviral agent.

As the first evidence began to come out about an emerging novel coronavirus from China, renewed interest came back towards Remdesivir, especially after the Ebola scare of 2014-2016 passed and interest in Remdesivir died down.

One of the most commonly cited in vitro studies comes from a study that I, interestingly enough, cited in my Hydroxychloroquine pieces.

In a study from Wang et. al. 2020, Vero E6 cells (kidney epithelial cells derived from monkeys) were infected with SARS-COV2. Afterwards, the cells were treated with several candidate therapeutics, with both Remdesivir and Chloroquine showing promising effectiveness.

It should be noted that this study included other therapeutics. However, the lower cytotoxicity and effective concentration made both Remdesivir and Chloroquine stand out as the best possible candidates.

Not many other in vitro studies were conducted during the early times of COVID, as it seemed that the prior studies conducted against other coronaviruses may have been evidence enough. The addition of the Wang et. al. 2020 study helped to further confirm additional evidence in favor of Remdesivir against SARS-COV2.

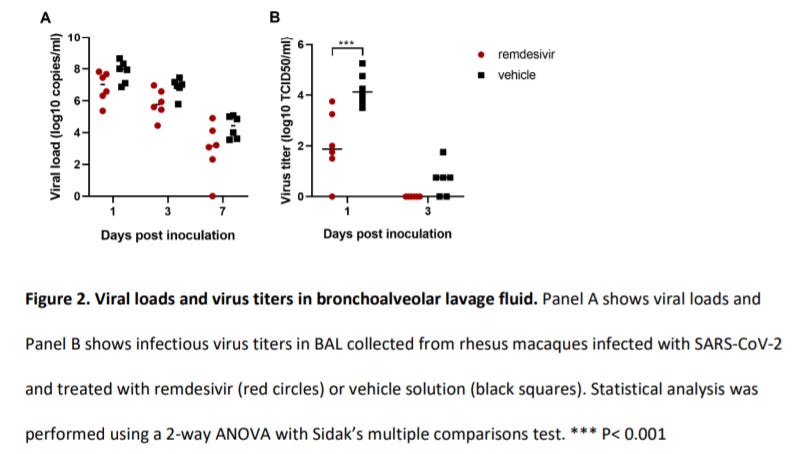

When it comes to animal trials, there was one study that looked at the effects of Remdesivir in rhesus macaques who were challenged with SARS-COV2. This study, conducted by Williamson et. al. 2020, used two groups of six rhesus macaques and provided Remdesivir to one group while the other only received the vehicle. The results of this study showed greater viral clearance in the treatment group compared to the control.

This would add even more evidence in favor of Remdesivir. However, the authors did note that the difference in SARS-COV2 infection rate between the macaques and humans may play a role in medication timing (emphasis mine):

Remdesivir is the first antiviral treatment with proven efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in an animal model of COVID-19. Remdesivir treatment in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2 was highly effective in reducing clinical disease and damage to the lungs. The remdesivir dosing used in rhesus macaques is equivalent to that used in humans; however, due to the acute nature of the disease in rhesus macaques, it is hard to directly translate the timing of treatment used to corresponding disease stages in humans. In our study, treatment was administered close to the peak of virus replication in the lungs as indicated by viral loads in bronchoalveolar lavages and the first effects of treatment on clinical signs and virus replication were observed within 12 hours. The efficacy of direct-acting antivirals against acute viral respiratory tract infections typically decreases with delays in treatment initation18. Thus, remdesivir treatment in COVID-19 patients should be initiated as early as possible to achieve the maximum treatment effect.

There continues to be more and more compounding evidence towards the idea of treatment timing. Even studies such as this from the beginning of the pandemic, and even beforehand with the Ebola study hint at the important nature of timing therapeutics as well as the importance of proper dosing.

Curious that this is something that has constantly been mentioned in the literature and yet still seems to present as a conundrum in the medical setting.

Unlike the prior years, the nonclinical evidence in favor of Remdesivir was limited. However, the combination of all of the prior in vitro coronavirus studies as well as the two studies I listed here helped to bolster support towards using Remdesivir in a clinical setting.

Clinical Evidence Against SARS-COV2

There’s a lot of information to go through here, all of which require some context and perspective. Be warned that some deep interpretations will be required for some of these studies, and any interpretation here will be based on my interpretation and not necessarily those of the researchers. So remember, as always to take what I state with a level of skepticism.

First off, it seems that the in-hospital regimen used for SARS-COV2 was taken directly from the Mulangu et. al. 2019 Ebola Virus study:

Patients in the remdesivir group received a loading dose on day 1 (200 mg in adults, and adjusted for body weight in pediatric patients), followed by a daily maintenance dose (100 mg in adults) starting on day 2 and continuing for 9 to 13 days, depending on viral load.

And this can be seen within an earlier version of the EUA Fact Sheet for Remdesivir.

It seems pretty weird that the same regimen was used for both Ebola and SARS-COV2, especially considering the difference in presentation and pathology between the two viruses. I don’t see any reason as to why this regimen was considered adequate without any trial evidence, and without that evidence it seems like this choice of regimen may have been haphazardly chosen based on whatever was found in the literature.

Considering that Remdesivir showed worse outcomes compared to the ZMapp group, this study also didn’t add anything relevant or significant to Remdesivir’s consideration when it came to drug efficacy.

So for now it seems like the protocol was immediately adopted from the Ebola Virus study without any careful considerations taken into account in differences in disease pathology.

It was this lack of any clinical evidence that likely led to the somewhat unnecessary Gilead-funded clinical trial.

In this randomized, open-label RCT conducted by Goldman et. al. 2020 (and funded by Gilead), researchers wanted to examine whether there would be a difference between a 5-day Remdesivir protocol and a 10-day protocol.

As taken from the Discussion (emphasis mine):

In this open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase 3 trial among patients with severe Covid-19 pneumonia due to infection with SARS-CoV-2, we did not find a significant difference in efficacy between 5-day and 10-day courses of remdesivir. After adjustment for baseline imbalances in disease severity, outcomes were similar as measured by a number of end points: clinical status at day 14, time to clinical improvement, recovery, and death from any cause. However, these results cannot be extrapolated to critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation, given that few of the patients in our trial were receiving mechanical ventilation before beginning treatment with remdesivir.

So the researchers (or really Gilead) found that a 10-day regimen may not be necessary and the dosage was later modified to 5 days for those not requiring ventilation or help breathing while those on a ventilator are provided a 10 day dosage.

Whether or not the rationale for such a modification came from this study, the researchers here clearly state that the results from this study cannot be used to extrapolate to patients on ventilators. Again, we are witnessing inconsistent policy that doesn’t seem to match up to any of the clinical evidence.

Even more frustrating, for those of us who lean heavily towards the side of “early treatment is best” we can see the possible damaging effects of such a policy where those are severely ill are prescribed an even greater dosage of an antiviral therapeutic, especially when viral invasion and replication is less likely to be occurring at this stage. The researchers even mention this as a possible reason for the discrepancy between the treatment groups:

The 10-day group included a significantly higher percentage of patients in the most severe disease categories — those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen — and a higher proportion of men (68%, vs. 60%), who are known to have worse outcomes with Covid-19.7

The researchers suggest that not enough patients on ventilators were included in the study to provide a comparative analysis, yet here they insinuate that better outcomes in the 5 day group could be attributed to the lack of mechanical ventilation in that group. Again, another strike in favor of early treatment and another strike against the incoherent dosing regimen that is still in use now. Do you see a pattern forming here?

But it doesn’t end there. We still don’t have any clinical evidence of Remdesivir’s effectiveness against SARS-COV2. Remember that this study did not include a control group so there is no group to use as a reference for efficacy. The researchers here even suggest as much that this study could not be used to provide any evidence of efficacy.

Nonetheless, I do want to point something out in regards to this study. There were reports of a high number of adverse and severe adverse events in this study (~74% for adverse events overall), and this was used as an indication that Remdesivir is causing severe damage. I would consider this to be a wrong interpretation of these results. Remember that adverse event refers to any worsening symptom or elevated biomarker that may be occurring during the administration of the therapeutic, unlike adverse reaction which are symptoms and elevated biomarkers that could be directly attributed to a drug.

Looking at the adverse event chart you can see some indications of kidney and liver damage (elevated levels of aminotransferases being one measure), but also some symptoms that are far more likely to be attributed to COVID (respiratory failure being one of them). It’s important to take the differences between these adverse events into consideration when considering adverse reactions from Remdesivir. These terms are not interchangeable and should also be examined within the context of both the drug and the disease. So when examining these studies don’t become sidetracked with the sudden reporting of adverse events in such a manner. A lack of any context will lead to a wrong interpretation as well as a wrong conclusion.

There’s a few more studies to get through so I will end the examination of this study by highlighting the large discrepancy between what the researchers here discuss and what is being put into practice. As we can see, nearly every policy put into place around Remdesivir runs counter to the actual evidence indicated in this study. I always try to operate off of an evidence-based standard, but yet it does not seem to be the case when it comes to those who are creating the policies around COVID therapeutics.

Another study was conducted by Wang et. al. 2020, in which outcomes were measured in Chinese patients based on evidence pooled from 10 Chinese hospitals. The treatment group was provided the typical Remdesivir dosage outlined above while the placebo group was provided a solution by Gilead (most likely the vehicle- this will be discussed later).

The results of this study suggest both no statistical difference in clinical outcomes as well as no statistical reduction in mortality, although both were numerically lower in the Remdesivir group. However, this study was stratified in a 2:1 ratio, so there were more patients in the Remdesivir group as compared to the placebo group, meaning that the numerical evidence would not be comparable to one another.

This study would lean towards a lack of effectiveness in regards to Remdesivir, if not for the incompleteness of this study. This study was not able to recruit enough participants, and so the question of whether is study is underpowered should be taken into consideration (it’s the reason for the 2:1 ratio instead of a 1:1 ratio).

What really stands out though is not that the study was incomplete, but why it was incomplete. The main reason the researchers were not able to recruit more patients was because, as was the narrative at the time, China got the coronavirus under control.

Now, whether or not you agree with China’s measures and their transparency as it comes to reporting cases, there’s no doubt that the results of this study have been tainted by politics and possible deception. I have to question the results of a study when it seems to have ended short of expectation because China’s lockdown policies were just too good! So much so that they wouldn’t even need a therapeutic!

Nonetheless, examining the results and data collected still suggest a lack of efficacy, and this study was reported widely including being reported by the WHO, who conducted their own study and found a lack of efficacy with Remdesivir as well. As a final note, this study was considered to have enrolled severely ill COVID-19 patients, and the inclusion criteria included symptom presentation up to 12 days prior- a long period of infection which, as should be fully obvious by now, suggests the importance of medication timing and symptom onset. It also matches the suggestions made by the Goldman et. al. study, such that severity of illness likely plays a contributing factor in clinical outcomes. Also, the evidence wasn’t there to suggest the utility of Remdesivir in those on a ventilator, although this study would point to a lack of efficacy in that scenario.

The evidence is mounting that context and timing is key when it comes to using Remdesivir. Of course, this should come as no surprise at this point. However, let’s look at some more evidence.

This section is a lot longer than expected so it will be continued in the next newsletter.