Long COVID: Valid Symptoms, or A Consequence of Mass Hysteria and Misinformation? (Paper Review & Perspective)

A recent French study calls into question the prevalence of a persistent COVID talking point.

Let’s face it, we’ve all done it at some point during the pandemic.

You hear about a strange illness coming from Wuhan. When the virus makes landfall, you being to hear about people getting ill. You constantly watch the news, hoping to get information about this strange new illness. But all you are told is that it is a “flu-like” illness that may lead to pneumonia.

And just like that you’ve become a member of the COVID-police, targeting any friend who may get too close, or any family member who even dares to cough!

And then it hits you, and you start to feel a tingle in your throat. You play it off thinking it’ll go away, but instead you start to feel a soreness develop, culminating into the dreaded cough.

Now you’ve done it, you’ve gone and gotten COVID! Or, it at least seems like COVID; you can’t be too sure, for all you know the symptoms of COVID are “flu-like” symptoms, and you certainly at least feel “fluish”. Regardless, you are not sure, but just to be safe let’s just say that it is, because you can never be too careful!

So this may be a bit hyperbolic, although I’ll admit that I may have been a bit too enthusiastic with my COVID accusations against family members (and I’m sure I’m not alone in doing so!).

Otherwise, we have all seen something similar to this play out; we were told that there is a pandemic of a “flu-like” illness spreading around, and so any feeling of unwellness may be attributed to COVID. After all, you can’t be too careful, and the symptoms do seem to match!

So what happens when millions of people, unaware of whether or not the illness they are feeling is actually COVID and not some cold or flu, begin to believe they are infected with COVID with no actual confirmatory test?

Well, a group of researchers in France wanted to find this out themselves. In this case, they looked at a group of French citizens and examined whether the persistence of long COVID symptoms was associated with an actual COVID infection or due to peoples perceptions of having had COVID.

The study, conducted by Matta et. al. 2021, was just released a few days ago in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), so let’s take a look.

Assessing the Study

The hypothesis the researchers started with consisted of the following:

Are the belief in having had COVID-19 infection and actually having had the infection as verified by SARS-CoV-2 serology testing associated with persistent physical symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic?

So here the researchers wanted to see if people who seem to be experiencing long COVID symptoms were actually infected (as confirmed by tests) or if they just believed that they had COVID.

And this is taken from the Introduction, which helps set up the reason for this study (emphasis mine):

After infection by SARS-CoV-2, both hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients have an increased risk of various persistent physical symptoms that may impair their quality of life, such as fatigue, breathlessness, or impaired attention.1-3 Although the term “long COVID” has been coined to describe these symptoms4 and putative mechanisms have been proposed,3,5,6 the symptoms may not emanate from SARS-CoV-2 infection per se but instead may be ascribed to SARS-CoV-2 despite having other causes. In this study, we examined the association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and of serology test results with persistent physical symptoms. We hypothesized that the belief in having been infected with SARS-CoV-2 would be associated with persistent symptoms while controlling for actual infection.

The important thing is to understand that this study is not intended to invalidate the idea of long COVID. Instead, it’s examining the relationship between self-reporting and actual prevalence of long COVID symptoms.

I won’t go deep into the study, just understand that it’s mainly comprised of a questionnaire asking people a few questions about their prior infection history, if they still had persistent symptoms, and what symptoms those were.

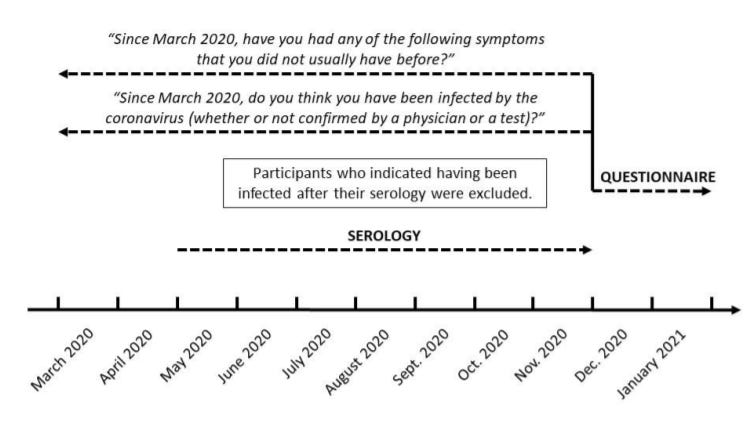

In order to check if participants had prior history of infection, researchers took blood samples from participants in order to check for the presence of antibodies. It’s important to note that the collection of blood samples occurred BEFORE the questionnaire was given.

The first set of questions asked whether the participant had COVID. Although I don’t want to post everything, I did notice this little bit from the first question:

Between December 2020 and January 2021, the participants answered this question from the fourth SAPRIS questionnaire: “Since March, do you think you have been infected by the coronavirus (whether or not confirmed by a physician or a test)?” Participants answered “Yes,” “No,” or “I don’t know.” At the time they answered this question, the participants were aware of their serology test results (eFigure in Supplement 1). A total of 2788 participants (7.8%) who answered “I don’t know” were excluded.

Now, I don’t know too much about research design, but this did pop out at me as a strange study design; people answered whether or not they believe they had previously been infected with COVID at the same time they also know whether they had antibodies. This is more of a minor gripe, but it seems strange to design the study around asking people to answer a questionnaire while also letting them know their seroprevalence results.

Again, more of a personal gripe but I just wanted to point this out.

Participants were then asked when they think they got COVID and whether they had confirmation from a test (PCR, antigen, serology, Doctor confirmation).

Afterwards, researchers asked questions to check for long COVID symptoms. Here, they asked participants one of the following question: “Since March 2020, have you had any of the following symptoms that you did not usually have before?”

It’s a bit of a weird, all-encompassing question, but we can probably predict how people will respond when we see the following symptoms:

sleep problems

joint pain

back pain

muscular pain, sore muscles

fatigue

poor attention or concentration

skin problems

sensory symptoms (pins and needles, tingling or burning sensation)

hearing impairment

constipation

stomach pain

headache

breathing difficulties

palpitations

dizziness

chest pain

cough

diarrhea

anosmia

and other symptoms

After seeing that list, can’t you just feel your inner hypochondriac stirring within you? It’s a long list, and we may see why someone may believe they have had COVID when asked these questions.

Finally, participants were then asked how long they had the symptoms and whether they attributed the symptoms to COVID.

Surprisingly (or unsurprisingly) the researchers found that people who believed they had COVID were more likely to associate their symptoms to COVID, than people who actually had COVID.

More surprisingly, people who did not have COVID but believed they did indicated that they experienced 15 out of the 18 symptoms.

Interpreting the Results

Here’s an excerpt from the Discussion (emphasis mine):

This cross-sectional analysis of data from a population-based cohort found that persistent physical symptoms 10 to 12 months after the COVID-19 pandemic first wave were associated more with the belief in having experienced COVID-19 infection than with having laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In previous studies, the association between persistent symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results may be explained by the belief in having experienced COVID-19 infection.13 Furthermore, most previous studies assessing “long COVID” included only patients who had COVID-19 infection, thus lacking a control group of patients who did not have the infection.3,14 Indeed, our results showed that the persistent physical symptoms observed after COVID-19 infection were quite frequent in the general population. Because our study also included participants who reported not having had COVID-19 infection with either positive or negative serology test results, we were able to compare the prevalence of persistent physical symptoms according to these 2 variables. We were also able to perform analyses restricted to participants attributing their persistent symptoms to COVID-19 infection. Although our study did not assess long COVID per se because we also included participants without COVID-19 infection, these specific analyses may be more representative of the long COVID clinical issue in real-life settings15 than the picture provided by cohorts of patients with a laboratory-confirmed or physician-documented COVID-19 infection.

Although this study was a self-report, the results encapsulate a lot of what’s wrong with the way COVID has been presented. Even now, most symptoms of COVID are explained as being “flu-like” in nature, a very broad range of symptoms to begin with. Coughing and sneezing comprise plenty of other diseases, and they don’t necessarily confirm COVID.

However, we did hear about other symptoms (shortness of breath and diarrhea, to name a few), but even then those symptoms are not unique to COVID. What’s even more concerning is that we began to see many health officials associate any type of symptom to COVID.

Take for example diarrhea being used as a confirmatory symptom. The use of this symptom didn’t help to confirm COVID (I think plenty of us Americans would have had COVID for years if that was the case!) because it was not backed by any causative relationship, just some observations. By now I don’t think many people even mention diarrhea as a symptom, but it was talked about plenty for the first few months. Just like the way many COVID deaths are reported as “from” COVID instead of “with” COVID, may symptoms seem to have been reported as coming “from” COVID and not symptoms from someone “With” COVID.

In this case, the haphazard messaging surrounding COVID made it difficult to really figure out what symptoms were unique to COVID. The data was tainted with all sorts of information. Doctors and medical professionals were unsure of what symptoms indicated COVID, but if someone who tested positive had it, it was likely to be added as a data point of possible symptoms.

It’s no wonder so many people were unsure of whether or not they had COVID, and that uncertainty has clearly transferred over into the realm of long COVID.

I was a victim of this haphazard messaging. When I had to return to work full time last summer I began to have a weird feeling of pins and needles in my throat (which I now attribute more to the chronic mask wearing), but I wasn’t sure what caused it at the time. As it got worse I became paranoid and believed it was COVID. I went to get a swab test, which turned out negative, but my throat still had that needly irritating feeling to it, which made me believe that my test was just negative. Remember how many people thought they had COVID, got a negative test, and attributed it to a faulty test?

Even now my throat feels irritated, but I also have a strange sensation in my nose (not anosmia), which I now attribute to both masks and the nose swabbing that took place 2-3 times a week when I was performing COVID testing. I tested negative all of those times, and even as I still experience some of these symptoms I wonder if I did actually catch COVID at some point.

It’s easy to understand why so many people may think they had COVID even if they test negative on both PCR or serology tests. When people are unable to make sense of their symptoms and their relationship to COVID, people may begin to have irrational lines of thinking. It seems that many people, unaware of if they were infected, are more likely to engage in confirmation bias and attribute anything they feel to possibly being COVID. Remember you can’t be too careful, and so it’s better to play it safe and say that what you experience is COVID, even if it doesn’t seem like a rational assessment.

Even now, I have one friend who is experiencing a cough and sore throat who thought she may have gotten COVID again (she recently tested negative after telling me her symptoms) while another friend is experiencing a very mild fever but has lost his sense of taste and smell (anosmia being one of the clearer signs of COVID).

Symptoms of COVID are extremely varied, possibly attributed to medical institutions have not been able to pin down precise, consistent symptoms that are most likely to indicate COVID (outside of anosmia and possibly shortness of breath). It’s a consequence of the way the disease manifests, as well as inconsistent messaging from medical officials.

Unfortunately, all of these issues in diagnosing has also tainted the realm of long COVID. When you are unaware if you actually had COVID, or if your symptoms were derived from prior COVID infections, you certainly will have difficulty determining if any of your symptoms can be traced to COVID and emblematic of long COVID.

This problem even arose among doctors who tried to treat long COVID since they had a lot of difficulty even determining if their patients ever had COVID (antibody tests weren’t so prevalent during the early COVID months).

But one of the most frustrating things, as it pertains to long COVID, is how much this has been used to push fear and hysteria. Whenever someone says that COVID is mostly severe for certain demographics, and most young people would likely fare well, the rebuttal has consistently been, “What about long COVID?!”. We see that even playing out with children and vaccinations, where many people who believe their children need to be vaccinated may also believe that they may experience long-term ramifications from infections, even when the evidence is hardly there for young children and spotty at best for adults.

But still this fear mongering persists, and so once again it comes as no surprise that many people, who can’t even tell if they have gotten COVID, may attribute any sense of unwellness to COVID.

This newsletter is running a little long, so I’ll summarize the takeaways and implications from this study:

Long COVID is Real

This is such a strange take that I’ve seen multiple people take over this study. No, this study does not argue that long COVID isn’t real; it was never intended to do such a thing. Instead, this study just calls into question the prevalence of long COVID, and instead argues that most long COVID symptoms may not actually be attributable to COVID itself. That doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist (we’d need more studies to figure that out) but that the rate of long COVID may be much lower than is being reported. Remember that studies should never be taken as absolutes, so be hesitant when someone reports on studies with absolutist language.

The Media & Medical Professionals have done a Disastrous Job around COVID Messaging

There’s no doubt that many of us have had difficulties figuring out whether a cough, a sneeze, or a sore throat meant that we got COVID. The presentation of COVID as predominately comprising “flu-like” symptoms is such a vague, nonspecific way of describing a disease, so it’s no wonder people can’t figure out what they have. This issue carries over into the realm of long COVID as well, and they’re predominately a consequence of horrendous messaging by medical professionals. When the people who we depend on can’t even give us direct ideas of what constitutes a COVID infection we shouldn’t be surprised when people act in such a haphazard manner. Sure, it’s a new disease which means the evidence is a work in progress, but constant waffling by the likes of Dr. Fauci and other officials doesn’t help to make any of the information any less confusing. Add in the fact that people were told to play it safe instead of sorry, and you can see why everything under the sun may be attributed to COVID.

Ironically, the Symptoms may be a Consequence of a Different Long COVID

There’s no doubt that lockdowns have caused many people to stop exercising, going outdoors, and eating properly. We have clear evidence that people have gained weight during the lockdowns, and that people have not socialized with one another to the same extent we did before. For more than a year people have been living predominately through Zoom, social media, and streaming services. Compounded with many people missing doctor’s appointments and checkups, we can see why self-reports of long COVID may be so high.

Many people were unwell before COVID, and lockdowns certainly didn’t help alleviate these issues. Take a look at the symptoms with the highest odds ratios: fatigue, poor attention or concentration, breathing difficulties, chest pain, and anosmia. Not only could these be attributed to COVID, but they overlap with other symptoms that have been raised over lockdowns. More people have become depressed and anxious (fatigue), but people have also lived a life shuffling between Zoom, Netflix and social media, all of which attribute to worse concentration. I also indicated that chronic mask wearing and nose prodding may have affected my breathing, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the same has occurred for many people as well.

So maybe long COVID is highly prevalent, but not because of actual COVID, but maybe due to the consequences of long term preventative measures that were taken to reduce infection. In that sense, it seems that the results of this study may also indicate symptoms of long-term COVID lockdown measures more than actual consequences of COVID infections.

This study shines a light on something that has plagued the discourse around COVID, and it calls into question the extent that long COVID is actually prevalent. What’s more important is that this may indicate that reports of long COVID may not be the fault of patients, but may be a consequence of media reporting, horrendous messaging, and incoherent lockdown measures that have left us all worse off. Know that this is how I, not the researchers, have interpreted the results, but the point still remains that context is important to understanding why the researchers found the results that they did.

Long COVID is real, and COVID is absolutely real, but what we may be witnessing is the downstream ramifications of improper messaging that has left millions of people as confused hypochondriacs who have become scared of their own friends and families.

Faith within the media and medical professionals are at an all time low, and both institutions should know that they should be transparent and direct with their messaging. Otherwise, we can see what happens when people are left misinformed. Hopefully, this study can serve as a wake up call for the need for more, proper reporting surrounding COVID.

Thank you for reading my newsletter. If you enjoy my articles please consider becoming a free subscriber in order to receive notifications.

And share with others who may find these newsletters interesting.

Also, please consider becoming a paid member. The research and work put into these articles takes many hours and being a paid subscriber allows me to continue to do this full time.

My conclusion reading this and other articles on the subject, is that long Covid is real but most of the time is not caused directly by Covid.

I'm late to discovering your substack, but reading some of the older posts now, and this one caught my eye. Another problem not considered is that the antibody testing is unreliable. My daughter got a fever at the end of a 2-week Asian trip that had connections in China in February 2020. Upon return, she was told she didn't have COVID because it had been more than 14 days since she'd been in China (it had been 15!). No PCR test was available in her area at that time. She ended up with many of the common issues including loss of taste/smell, breathlessness, hair loss, GI issues, circulation issues in extremities, ground glass opacity in CT scan of lungs, cardiac arrhythmia, fatigue, and more. Had a rough go of it for a couple weeks (not hospitalized; no treatments available) but recovered from the acute phase. She then had continuation of many symptoms for months, and at 2 years is still not fully recovered. She was a very fit endurance athlete who had run a 50 mile ultramarathon a couple months before the trip and was training for a 100-miler but had to give it up. She couldn't walk her dog 10 steps without having to stop for breath, and many days just couldn't get out of bed. When a PCR test was finally available, she took it but was negative; not surprising, as this was months after acute infection. When antibody test was available much later, that too was negative. At that time other long-haulers, including those who HAD had a positive PCR test, reported antibody testing in online user support group surveys, and about 40% had negative tests. About 9 months after infection she was able to receive an inflammatory marker test panel developed by Dr. Bruce Patterson at IncellDx and it showed her to be significantly inflamed. More specifically, the "fingerprint" of her markers (about 15 of them IIRC) matched that of confirmed post-COVID long-haulers. IncellDx has published development of a "long-haulers index" based on a common fingerprint pattern observed in PCR-confirmed post-covid long-hauler patients. My daughter matched that fingerprint. More recently, when it became available, she took the new T-cell test but it, too, was negative. So, thus far, she has every reason to believe it was COVID based on timing, location of infection, symptoms, and the IncellDx test, but no direct genomic confirmation of the virus, viral fragments or antibodies.

All of this to say that studies like you discussed need to consider that people COULD have post-covid long-haulers syndrome without testing positive for antibodies. They would do well to use a broader spectrum of testing methods, especially before attributing anything to psychosomatic effects. The last thing long-suffering patients need is to be gaslighted. Too many are. My daughter ran into that too, though at least with the CT scan they couldn't say it was ALL in her head. But they tended to say she just had a pulmonary problem without considering the true origin and nature of the illness.