July's Post: Science Jumping the Shark

A look at how sweeping generalizations and bad science can influence how we interpret research.

For the most part COVID has been a Godsend for those who have never considered taking a glimpse into the world of science. The inundation of open-access articles has allowed every layperson and their mother the ability to read articles without having to pay up to $100 for the mere privilege to have limited access to an article that may end up being worthless.

But similar to Uncle Ben reminding Peter Parker that great power comes with great responsibility, so too does the pursuit of knowledge come with great responsibility. Knowledge is, after all, power, and how we use and apply knowledge requires a lot of responsibility. As simple as the act of reading a science article may appear, it takes a ton of background knowledge and an understanding of how to parse and interpret the information in order to properly disseminate what’s being read.

More importantly, it requires that we show some level of restraint when we read articles, yet it appears instead that the opposite may be occurring. Instead, it appears that in a never-ending sea of COVID articles we may just be fishing for whatever articles promote our biases even if the evidence is unsubstantiated. If the ideas sound fitting, we may take them as use them as our own. If not, then we may squeeze an article for some hypothesis or conclusion that was never really substantiated by the initially provided evidence. In essence, there’s been an approach to interpretations of COVID science that “jumps the shark” and goes farther than should be normally allowed when piecing together information and results.

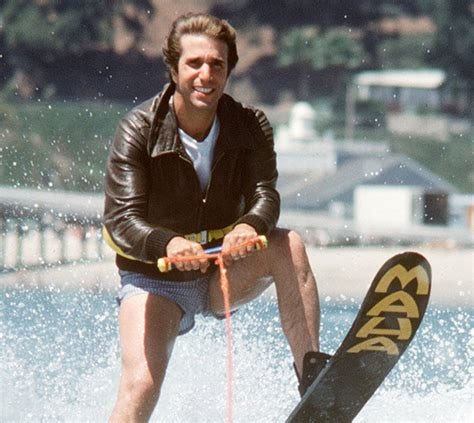

“Jumping the shark” as an idiom comes way before my time, but it’s derived from an episode of Happy Days in which Fonzie jumps over a shark while on water-skis. This episode comes after the show apparently showed a decline in ratings and popularity, with the idiom being used in reference to other forms of entertainment that begin to lose popularity and may resort to novel, absurd ideas in order to gain back viewership or attention.

As it relates to science, I am using the idiom as a reference to when science as a field sacrifices actual scientific methodology in order to appear more flashy and appealing to the public. It’s taking novel scientific ideas and popularizing them even if the science itself is not readily substantiated because it makes for a talking point more than for good science.

Time and time again I am seeing more articles used not to piece information together, but to serve as some point of pontification based on tenuous associations that may be eye catching or serve as some talking point.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Modern Discontent to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.